The world’s fossil-fuel use is still on track to peak before 2030, despite a surge in political support for coal, oil and gas, according to data from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The IEA’s latest World Energy Outlook 2025, published during the opening days of the COP30 climate summit in Brazil, shows coal at or close to a peak, with oil set to follow around 2030 and gas by 2035, based on the stated policy intentions of the world’s governments.

Under the same assumptions, the IEA says that clean-energy use will surge, as nuclear power rises 39% by 2035, solar by 344% and wind by 178%.

Still, the outlook has some notable shifts since last year, with coal use revised up by around 6% in the near term, oil seeing a shallower post-peak decline and gas plateauing at higher levels.

This means that the IEA expects global warming to reach 2.5C this century if “stated policies” are implemented as planned, up marginally from 2.4C in last year’s outlook.

In addition, after pressure from the Trump administration in the US, the IEA has resurrected its “current policies scenario”, which – effectively – assumes that governments around the world abandon their stated intentions and only policies already set in legislation are continued.

If this were to happen, the IEA warns, global warming would reach 2.9C by 2100, as oil and gas demand would continue to rise and the decline in coal use would proceed at a slower rate.

This year’s outlook also includes a pathway that limits warming to 1.5C in 2100, but says that this would only be possible after a period of “overshoot”, where temperature rise peaks at 1.65C.

The IEA will publish its “announced pledges scenario” at a later date, to illustrate the impact of new national climate pledges being implemented on time and in full.

(See Carbon Brief’s coverage of previous IEA world energy outlooks from 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016 and 2015.)

World energy outlook

The IEA’s annual World Energy Outlook (WEO) is published every autumn. It is regarded as one of the most influential annual contributions to the understanding of energy and emissions trends.

The outlook explores a range of scenarios, representing different possible futures for the global energy system. These are developed using the IEA’s “global energy and climate model”.

The latest report stresses that “none of [these scenarios] should be regarded as a forecast”.

However, this year’s outlook marks a major shift in emphasis between the scenarios – and it reintroduces a pathway where oil and gas demand continues to rise for many decades.

This pathway is named the “current policies scenario” (CPS), which assumes that governments abandon their planned policies, leaving only those that are already set in legislation.

If the world followed this path, then global temperatures would reach 2.9C above pre-industrial levels by 2100 and would be “set to keep rising from there”, the IEA says.

The CPS was part of the annual outlook until 2020, when the IEA said that it was “difficult to imagine” such a pathway “prevailing in today’s circumstances”.

It has been resurrected following heavy pressure from the US, which is a major funder of the IEA that accounts for 14% of the agency’s budget.

For example, in July Politico reported “a ratcheted-up US pressure campaign” and “months of public frustrations with the IEA from top Trump administration officials”. It noted:

“Some Republicans say the IEA has discouraged investment in fossil fuels by publishing analyses that show near-term peaks in global demand for oil and gas.”

The CPS is the first scenario to be discussed in detail in the report, appearing in chapter three. The CPS similarly appears first in Annex A, the data tables for the report.

The second scenario is the “stated policies scenario” (STEPS), featured in chapter four of this year’s outlook. Here, the outlook also includes policies that governments say they intend to bring forward and that the IEA judges as likely to be implemented in practice.

In this world, global warming would reach 2.5C by 2100 – up marginally from the 2.4C expected in the 2024 edition of the outlook.

Beyond the STEPS and the CPS, the outlook includes two further scenarios.

One is the “net-zero emissions by 2050” (NZE) scenario, which illustrates how the world’s energy system would need to change in order to limit warming in 2100 to 1.5C.

The NZE was first floated in the 2020 edition of the report and was then formally featured in 2021.

The report notes that, unlike in previous editions, this scenario would see warming peak at more than 1.6C above pre-industrial temperatures, before returning to 1.5C by the end of the century.

This means it would include a high level of temporary “overshoot” of the 1.5C target. The IEA explains that this results from the “reality of persistently high emissions in recent years”. It adds:

“In addition to very rapid progress with the transformation of the energy sector, bringing the temperature rise back down below 1.5C by 2100 also requires widespread deployment of CO2 removal technologies that are currently unproven at large scale.”

Finally, the outlook includes a new scenario where everyone in the world is able to gain access to electricity by 2035 and to clean cooking by 2040, named “ACCESS”.

While the STEPS appears second in the running order of the report, it is mentioned slightly more frequently than the CPS, as shown in the figure below. The CPS is a close second, however, whereas the IEA’s 1.5C pathway (NZE) receives a declining level of attention.

Number of mentions of each scenario per 100 pages of text. Source: Carbon Brief analysis.

US critics of the IEA have presented its stated policies scenario as “disconnected from reality”, in contrast to what they describe as the “likely scenario” of “business as usual”.

Yet the current policies scenario is far from a “business-as-usual” pathway. The IEA says this explicitly in an article published ahead of the outlook:

“The CPS might seem like a ‘business-as-usual’ scenario, but this terminology can be misleading in an energy system where new technologies are already being deployed at scale, underpinned by robust economics and mature, existing policy frameworks. In these areas, ‘business as usual’ would imply continuing the current process of change and, in some cases, accelerating it.”

In order to create the current policies scenario, where oil and gas use continues to surge into the future, the IEA therefore has to make more pessimistic assumptions about barriers to the uptake of new technologies and about the willingness of governments to row back on their plans. It says:

“The CPS…builds on a narrow reading of today’s policy settings…assuming no change, even where governments have indicated their intention to do so.”

This is not a scenario of “business as usual”. Instead, it is a scenario where countries around the world follow US president Donald Trump in dismantling their plans to shift away from fossil fuels.

More specifically, the current policies scenario assumes that countries around the world renege on their policy commitments and fail to honour their climate pledges.

For example, it assumes that Japan and South Korea fail to implement their latest national electricity plans, that China fails to continue its power-market reforms and abandons its provincial targets for clean power, that EU countries fail to meet their coal phase-out pledges and that US states such as California fail to extend their clean-energy targets.

Similarly, it assumes that Brazil, Turkey and India fail to implement their greenhouse gas emissions trading schemes (ETS) as planned and that China fails to expand its ETS to other industries.

The scenario also assumes that the EU, China, India, Australia, Japan and many others fail to extend or continue strengthening regulations on the energy efficiency of buildings and appliances, as well as those relating to the fuel-economy standards for new vehicles.

In contrast to the portrayal of the stated policies scenario as blindly assuming that all pledges will be met, the IEA notes that it does not give a free pass to aspirational targets. It says:

“[T]argets are not automatically assumed to be met; the prospects and timing for their realisation are subject to an assessment of relevant market, infrastructure and financial constraints…[L]ike the CPS, the STEPS does not assume that aspirational goals, such as those included in the Paris Agreement, are achieved.”

Only in the “announced pledges scenario” (APS) does the IEA assume that countries meet all of their climate pledges on time and full – regardless of how credible they are.

The APS does not appear in this year’s report, presumably because many countries missed the deadlines to publish new climate pledges ahead of COP30.

The IEA says it will publish its APS, assessing the impact of the new pledges, “once there is a more complete picture of these commitments”.

Fossil-fuel peak

In recent years, there has been a significant shift in the IEA’s outlook for fossil fuels under the stated policies scenario, which it has described as “a mirror to the plans of today’s policymakers”.

In 2020, the agency said that prevailing policy conditions pointed towards a “structural” decline in global coal demand, but that it was too soon to declare a peak in oil or gas demand.

By 2021, it said global fossil-fuel use could peak as soon as 2025, but only if all countries got on track to meet their climate goals. Under stated policies, it expected fossil-fuel use to hit a plateau from the late 2020s onwards, declining only marginally by 2050.

There was a dramatic change in 2022, when it said that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting global energy crisis had “turbo-charged” the shift away from fossil fuels.

As a result, it said at the time that it expected a peak in demand for each of the fossil fuels. Coal “within a few years”, oil “in the mid-2030s” and gas ”by the end of the decade”.

This outlook sharpened further in 2023 and, by 2024, it was saying that each of the fossil fuels would see a peak in global demand before 2030.

This year’s report notes that “some formal country-level [climate] commitments have waned”, pointing to the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement.

The report says the “new direction” in the US is among “major new policies” in 48 countries. The other changes it lists include Brazil’s “energy transition acceleration programme”, Japan’s new plan for 2040 and the EU’s recently adopted 2040 climate target.

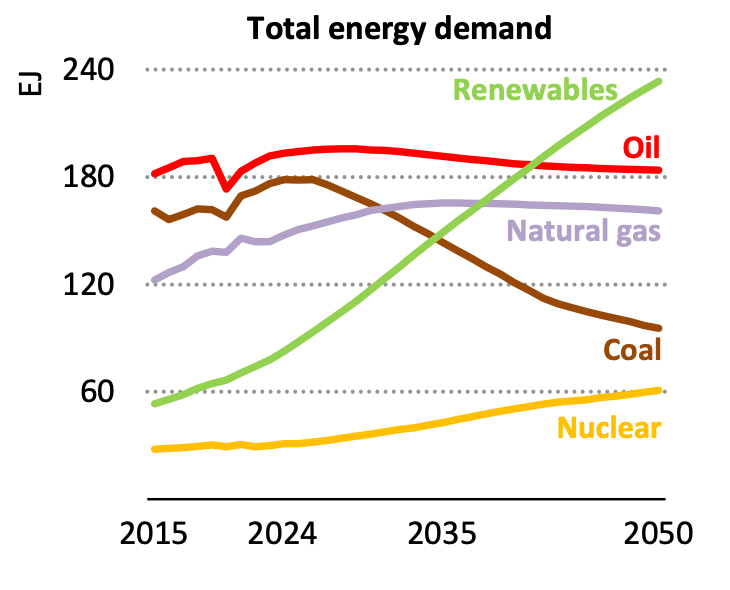

Overall, the IEA data still points to peaks in demand for coal, oil and gas under the stated policies scenario, as shown in the figure below.

Alongside this there is a surge in clean technologies, with renewables overtaking oil to become the world’s largest source of energy – not just electricity – by the early 2040s.

In this year’s outlook under stated policies, the IEA sees global coal demand as already being at – or very close to – a definitive peak, as the chart above shows.

Coal then enters a structural decline, where demand for the fuel is displaced by cheaper alternatives, particularly renewable sources of electricity.

The IEA reiterates that the cost of solar, wind and batteries has respectively fallen by 90%, 70% and 90% since 2010, with further declines of 10-40% expected by 2035.

(The report notes that household energy spending would be lower under the more ambitious NZE scenario than under stated policies, despite the need for greater investment.)

However, this year’s outlook has coal use in 2030 coming in some 6% higher than expected last year, although it ultimately declines to similar levels by 2050.

For oil, the agency’s data still points to a peak in demand this decade, as electric vehicles (EVs) and more efficient combustion engines erode the need for the fuel in road transport.

While this sees oil demand in 2030 reaching similar levels to what the IEA expected last year, the post-peak decline is slightly less marked in the latest outlook, ending some 5% higher in 2050.

The biggest shift compared with last year is for gas, where the IEA suggests that global demand will keep rising until 2035, rather than peaking by 2030.

Still, the outlook has gas demand in 2030 being only 7% higher than expected last year. It notes:

“Long-term natural gas demand growth is kept lower than in recent decades by the expanding deployment of renewables, efficiency gains and electrification of end-uses.”

In terms of clean energy, the outlook sees nuclear power output growing to 39% above 2024 levels by 2035 and doubling by 2050. Solar grows nearly four-fold by 2035 and nearly nine-fold by 2050, while wind power nearly triples and quadruples over the same periods.

Notably, the IEA sees strong growth of clean-energy technologies, even in the current policies scenario. Here, renewables would still become the world’s largest energy source before 2050.

This is despite the severe headwinds assumed in this scenario, including EVs never increasing from their current low share of sales in India or the US.

The CPS would see oil and gas use continuing to rise, with demand for oil reaching 11% above current levels by 2050 and gas climbing 31%, even as renewables nearly triple.

This means that coal use would still decline, falling to a fifth below current levels by 2050.

Finally, while the IEA considers the prospect of global coal demand continuing to rise rather than falling as expected, it gives this idea short shrift. It explains:

“A growth story for coal over the coming decades cannot entirely be ruled out but it would fly in the face of two crucial structural trends witnessed in recent years: the rise of renewable sources of power generation, and the shift in China away from an especially coal-intensive model of growth and infrastructure development. As such, sustained growth for coal demand appears highly unlikely.”

The post IEA: Fossil-fuel use will peak before 2030 – unless ‘stated policies’ are abandoned appeared first on Carbon Brief.

From Carbon Brief via this RSS feed