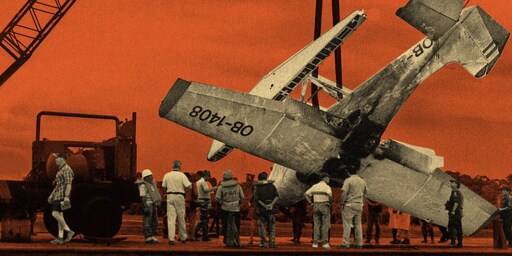

Veronica and Charity Bowers, a young Christian missionary and her daughter, are killed when the Peruvian Air Force shoots down a small passenger plane in 2001. The plane had been mistaken for a drug smuggling plane and was shot down as part of a joint anti-drug agreement between the CIA and the Colombian and Peruvian governments.

President Donald Trump has made the Bowers’s deaths newly and urgently relevant since he began ordering the U.S. military to strike down alleged drug smuggling boats in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific Ocean in September 2025. By early November, the U.S. had launched a total of 17 strikes, killing at least 70 people, and those figures seem to grow almost by the day. The attacks are illegal under both U.S. and international law. The administration also provided no documentation of the alleged drug trafficking.

The attack on the Bowers family pierced the veil that obscures drug war foreign policy because of their nationality, skin color, and relatability. More than 20 years ago, House Oversight Committee hearing members Jan Schakowsky and Elijah Cummings demanded accountability after U.S. drug interdiction forces killed the Bowers. They demanded to know how such a mistake could happen, and how we could prevent the loss of innocent life going forward.

“The kind of action we saw in Peru … amounts to an extrajudicial killing,” said Schakowsky at the time. Cummings added, “The Peruvian shootdown policy would never be permitted as a domestic United States policy precisely because it goes against one of our most sacred, due process principles — namely, that all persons are presumed innocent until proven guilty.”

[

Related

Trump Administration Admits It Doesn’t Know Who Exactly It’s Killing in Boat Strikes](https://theintercept.com/2025/10/31/trump-venezuela-boat-strikes-unprivileged-belligerants/)

Now, a new administration openly celebrates summary execution of alleged drug smugglers without a hint of due process, and is now threatening to topple another government to prevent the U.S. from sating its appetite for illicit drugs.

The story of Veronica and Charity Bowers is a stark reminder of how aggressive drug policy is wasteful and futile, how we never seem to learn from past failures, and how the generations-long effort to stop people from getting high also — and necessarily — treats human lives as expendable.

Transcript

Radley Balko: It’s April 20, 2001. In the skies above the Peruvian Amazon, a small floatplane flies over the rainforest, along the river. There are five people aboard. They don’t know it, but their plane is being tracked. A U.S.-based surveillance plane — contracting with the CIA — is closely following.

U.S. Pilot 1: We’re trying to remain covert at this point, but what we do know is it’s a high-wing single-engine floatplane that we picked up just along the border between Peru and Brazil.

Radley Balko: Working with the CIA contractors, a plane from the Peruvian Air Force begins to pursue the mystery plane. It doesn’t appear to have an authorized flight plan, and it isn’t responding to their radio messages. The CIA and Peruvian government suspect that it could be trafficking illicit drugs.

In one telling exchange, the piloting crew discuss whether they should try to identify the plane. But the U.S. officer directs them to stay covert. They’re concerned that the plane might get away.

U.S. Pilot 1: You know, we can go up and attempt the tail number, but the problem with that, if he is dirty and he detects us, he makes a right turn immediately and we can’t chase him.

U.S. Pilot 2: See, I don’t know if this is bandido or if it’s amigo, OK?

Peruvian Air Force pilot: OK.

U.S. Pilot 2 (in Spanish): I don’t know.

Radley Balko: That’s one of the CIA contractors, speaking really poor Spanish, telling the Peruvian Air Force pilot that he’s not sure if the plane in question is a “bandito” or “amigo” — a bandit or a friend.

The plane was then given multiple warnings to land.

Peruvian Air Force pilot (in Spanish): If you do not comply, we will proceed to take you down.

U.S. Pilot 2: This guy doesn’t, this guy doesn’t fit the profile.

U.S. Pilot 1: OK, I understand this is not our call, but this guy is at 4,500 feet. He is not taking any evasive action. I recommend we follow him. I do not recommend “Phase 3” at this time.

Radley Balko: “Phase 3” is code for the most drastic action possible: shooting the plane down from the sky. Under an agreement between the United States and the governments of Peru and other Latin American countries, any planes suspected of running drugs in the region could be plucked from the clouds.

That effectively put U.S. officials from the CIA or Drug Enforcement Agency — along with officials in the Peruvian government — in the role of judge, jury, and executioner.

Peruvian Air Force pilot: It’s three phase, authorized, OK?

U.S. Pilot 2: OK. But you sure it’s bandito? Are you sure?

Peruvian Air Force pilot: Yes.

U.S. Pilot 2: It’s bad? OK.

Peruvian Air Force pilot: OK.

U.S. Pilot 2: If you sure.

Peruvian dispatch: Tucan, Tucan, autorizado fase 3.

U.S. Pilot 1: I think we’re making a mistake, but—

U.S. Pilot 2: I agree with you.

Radley Balko: You can hear the hesitancy in their voices, in their words. And there’s good reason to be unsure. It turns out that in addition to the pilot, the plane is carrying a family of American missionaries: Jim and Veronica Bowers and their two children, 6-year-old Cody and 7-month-old Charity.

The pilot had actually been in touch with a control tower down below in the town of Iquitos but on a different radio frequency. But by the time the CIA and Peruvian Air Force realize their mistake, it’s too late.

U.S. Pilot 2: [unintelligible]

Peruvian Air Force pilot: Sí.

U.S. Pilot 2: He’s going to Santa Clara now.

Peruvian dispatch: Approximente 30 mille de Iquitos.

U.S. Pilot 2: The plane is talking to Iquitos tower.

Bowers’s Pilot (in Spanish): They’re killing us! They’re killing us!

U.S. Pilot 1: Tell them to terminate.

U.S. Pilot 2: Don’t shoot!

U.S. Pilot 1: Tell them to terminate. No más!

Radio chatter: Roger. No más, no más! Tucano, no más!

Radley Balko: As gunfire strikes the floatplane, the pilot screams, “They’re killing us. They’re killing us.” The plane then drops from the sky, leaving a streak of smoke as it plummets on to the Amazon river. The whole thing is caught on video by the CIA observers.

U.S. Pilot 1: There’s a plane right there. Where’s the plane?

U.S. Pilot 3: See them? And there’s the people getting them.

U.S. Pilot 2: Yeah, but I don’t see the plane. …

U.S. Pilot 3: It’s upside down. See, the float’s upside down and the people getting them? Right there.

U.S. Pilot 2: Yeah. Yeah. OK.

U.S. Pilot 3: There’s a bunch of boats down there.

U.S. Pilot 1: Yeah, I only see one. Oh, over here by the—

U.S. Pilot 2: You got a good, good film of that?

U.S. Pilot 1: Uh-huh.

U.S. Pilot 2: OK. Let’s go.

Radley Balko: Miraculously, Jim Bowers and his son Cody survive the crash, as does the pilot, despite being shot in the leg. But Veronica Bowers and 7-month old Charity are killed by gunfire before the plane goes down. The incident quickly makes international news.

George W. Bush: The incident that took place in Peru is a terrible tragedy. And our hearts go out to the families who have been affected.

Radley Balko: But as is often the case with the drug war’s collateral damage, no one would be held accountable.

Brian Ross (ABC Nightline): In Congress today, the CIA was accused by a top Republican of running a nine-year-long effort to stonewall and mislead Congress, failing to reveal how and why all of the program’s strict rules were ignored by the CIA.

Pete Hoekstra (on ABC): If the rules as outlined had been followed, the Bowers plane would not — would not — have been shot down.

Garnett Luttig (on ABC): I want to know the truth. I want to know why. I wonder why my baby’s gone.

Radley Balko: The CIA had been working with the governments of Peru and Colombia to shoot down planes they suspected of carrying drugs for years. We don’t know how many times it happened or how many of the victims were innocent, because the people in almost all of those planes weren’t American citizens. So there was no media outrage. No congressional hearings. No demands for transparency from powerful people.

Rep. Jan Schakowsky: We have spent billions of taxpayer dollars, employed personnel from numerous agencies around the world, and the drugs continue to flow into the United States. Are the Bowers acceptable collateral damage in this war on drugs?

Ian Vásquez: The drug war creates all sorts of innocent victims. People who may have absolutely nothing to do with the drug war, which of course was the case with the shootdown of the airplane in Peru. That was a mistake, but it was directly related to bad policy that Peru was following with the help of the United States.

Radley Balko: As we were producing this episode, President Donald Trump’s administration made the Bowers’s deaths newly and urgently relevant.

In early September 2025, Trump announced that he’d ordered the military to strike a small boat in the Caribbean that he claimed was being used by drug traffickers. Eleven people, all believed to be Venezuelan, were killed.

[

Related

Trump Administration Conjures Up New “Terrorist” Designation to Justify Killing Civilians](https://theintercept.com/2025/10/01/trump-venezuela-boat-strike-designated-terror-organization/)

The attack was illegal under both U.S. and international law. The administration also provided no documentation of the alleged drug trafficking. The U.S. military then expanded its attacks to include the eastern Pacific Ocean. By early November, the U.S. had launched a total of 17 strikes, killing at least 70 people, and those figures seem to grow almost by the day.

The attack on the Bowers family pierced the veil that obscures drug war foreign policy because of their nationality, their skin color, and their relatability. Even Republicans criticized how the George W. Bush administration reacted.

But we now face a brazen new administration that has carried out multiple extrajudicial executions in international waters — one that even jokes about how some of those they’ve killed may actually be innocent.

Donald Trump: I don’t know about the fishing industry. If you want to go fishing, a lot of people aren’t deciding to even go fishing.

JD Vance: [Crowd laughter] I would stop, too. Hell, I wouldn’t go fishing right now in that area of the world. [laughter]

Radley Balko: It’s also an administration now openly preparing to invade Venezuela under the pretext of fighting a drug war.

The story of Veronica and Charity Bowers is a stark reminder of how aggressive drug policy is wasteful and futile, how we never seem to learn from past failures, and how the generations-long effort to stop people from getting high also — and necessarily — treats human lives as expendable.

From The Intercept, this is Collateral Damage.

I’m Radley Balko. I’m an investigative journalist who has been covering the drug war and the criminal justice system for more than 20 years.

The so-called “war on drugs” began as a metaphor to demonstrate the country’s fervent commitment to defeating drug addiction, but the “war” part quickly became all too literal.

When the drug war ramped up in the 1980s and 1990s, it brought helicopters, tanks, and SWAT teams to U.S. neighborhoods. It brought dehumanizing rhetoric, and the suspension of basic civil liberties protections.

All wars have collateral damage: the people whose deaths are tragic but deemed necessary for the greater cause. But once the country dehumanized people suspected of using and selling drugs, we were more willing to accept some collateral damage.

In the modern war on drugs — which dates back more than 50 years to the Nixon administration — the United States has produced laws and policies ensuring that collateral damage isn’t just tolerated, it’s inevitable.

This is Episode 6, “Airborne Imperialism: The Tragic Deaths of Veronica and Charity Bowers.”

[

Collateral Damage Podcast

Collateral Damage](https://theintercept.com/podcasts/collateral-damage/)

It could be difficult to remember how the world worked, and how it felt, back before the attacks of September 11, 2001. It was easier to fly then. People felt safer. Life was less complicated. Former congressman Pete Hoekstra certainly thought so.

Pete Hoekstra: So it’s 2001, everything in America is great. I got on the [House] Intelligence Committee in January of 2001.

Radley Balko: Hoekstra, a Republican, was serving his fifth term in Congress, representing Michigan’s 2nd District.

Pete Hoekstra: Someone from West Michigan called me and said, “Hey, a couple of your constituents have died in Peru. They were shot down. What can you find out about this?” And so that’s when you go to the Intelligence Committee and say, “All right, will you help me take a look at the circumstances of this tragic event? Two of my constituents are killed. It appears that the CIA may have been involved in this. And I just want to get as much information as I can.”

Radley Balko: During his time in Congress, Hoekstra hadn’t focused much on either the drug war or on Latin America. But now two of his constituents were dead because of an incomprehensible mistake. So he had some catching up to do.

Pete Hoekstra: And so I still remember George Tenet coming — who at that time is the director of the CIA — and comes in to brief the Intelligence Committee. And it was a fascinating hearing. It’s when we actually, in Congress, on the Intelligence Committee, we did things in a bipartisan way. And so Tenet comes in, and he explains to us exactly what happens. And the director says, “There’s a protocol in place. And every step in the protocol was followed.” So basically justifying the shootdown of the Bowers plane.

Radley Balko: But then one of Hokestra’s colleagues spoke up.

Pete Hoekstra: It was one of the Democrats, says, “Mr. Director, do you have an audio or a video capturing the events of that day, of that flight, of that interdiction?” And he kind of says no, there’s no recording. He looks around. There’s a little commotion in the wall by someone sitting against the wall. And Tenet looks around, and the guy whispers something to the director, and the director says, “Excuse me, I am mistaken. There are recordings of exactly what happened at that event.”

Radley Balko: It seems unlikely that the CIA wouldn’t have known that there was video of the incident. Perhaps Tenet wanted to keep the damning footage away from Congress and the public. Or perhaps someone further down at the CIA wanted that, and so they never told Tenet that it existed. Hoekstra isn’t sure. But that recording prevented the incident from being swept under the rug. It made the deaths of Veronica and Charity Bowers an explosive international story.

Pete Hoekstra: If my Democratic colleague had not asked the question — “Is there a video or an audio tape of what happened before that shootdown?” — if he had not asked that question, that first hearing might have been the end of it.

Radley Balko: Instead, it was just the beginning.

Ray Suarez (PBS NewsHour): Peru and the United States offered differing views today on the downing of a missionary plane.Newscaster (ABC): According to senior administration officials, the Citation V surveillance plane used in the operation is owned by the Pentagon. Its crew was hired by the CIA from a private contractor.

Richard Boucher (State Department spokesperson): The father, Jim Bowers, the son, Cory Bowers, and the pilot, Kevin Donaldson, returned to the United States on Sunday. We think that the remains of the mother, Veronica Bowers, and the daughter, Charity, can be brought back to the United States today, and we’re assisting with that as well.

[Funeral organ music]

Radley Balko: The memorial service for Charity Bowers and her mom Veronica, known as Roni by those closer to her, was broadcast by a Grand Rapids, Michigan, TV station.

Jim Kramer (Bowers’ friend): Shall we pray? Dear Heavenly Father, we have come here today to honor your servant — your faithful servant — Roni Bowers, and her baby girl, Charity. We thank you, dear God, for the confidence that we have that they are with you right now in Heaven.

Radley Balko: Here’s Jim Bowers speaking at his wife and daughter’s memorial.

Jim Bowers: We were shot down right over a town of witnesses, which helped at the very beginning. And some of them were very good friends of mine. Incredibly, the town had a radio in which we were able to call for help. That’s very unusual. And the radio worked.

Radley Balko: The incident was difficult for some in the community to comprehend. As missionaries, the Bowers were deeply religious people. And Hoekstra, a Republican, was generally supportive of the drug war, as were most of the people in his conservative district.

That’s also true of Jim Bowers himself, who was torn about doing an interview with us, and ultimately declined. In an unrecorded call, Bowers emphasized to me that while he thinks the drug war has clearly gone too far in some ways, he’s opposed to legalizing or decriminalizing drugs, including marijuana. But Bowers does support ending the CIA operation that killed his wife and daughter, known as the “Air Bridge Denial Program.”

Here’s President George W. Bush describing it, as questions raged about the tragedy in Peru.

George W Bush: Our government is involved with helping — and a variety of agencies are involved — with helping our friends in South America identify airplanes that might be carrying illegal drugs. These operations have been going on for quite a while. We’ve suspended such flights until we get to the bottom of the situation to fully understand all the facts.

Radley Balko: The U.S. government restarted the operation just two years later in Colombia, but shut it down in Peru. They made minor protocol tweaks, adding supervisors to enforce rules, setting Spanish language fluency standards, and creating a dedicated communication channel. But protocols weren’t really being followed in the first place. And what’s more, Air Bridge Denial was just one part of a much broader, much more destructive U.S. policy in Latin America.

PBS NewsHour: The Latin America drug connection is where our major attention goes tonight. The State Department issued a major report on the subject today as part of a process aimed at denying U.S. aid to countries that fail to act against drug trafficking. It’s a story of politics and murder, corruption, and revolution — a story that grows more sensational with most passing recent days.

Radley Balko: Coca is a crop that’s been cultivated in Latin America for centuries. It has medicinal, nutritional, and religious uses. But of course coca is also used to make cocaine. It was a crop that had not only been a part of Andean culture dating back to pre-Colombian times, but due to Western appetites, it had become extremely lucrative for farmers in an impoverished part of the world.

And by the mid-1980s, the United States was facing twin epidemics fueled by the rise of the crack form of the drug — both in overdose deaths and in black-market violence as distributors fought over turf. So the U.S. government provided foreign aid, military training, and weapons to the Peruvian authorities to halt the cultivation of coca.

Ian Vásquez: In the 1990s in Peru, there was a concerted effort to go against the production of drugs. And what that led to, at that time Peru was the world’s largest producer of coca.

Radley Balko: That’s Ian Vásquez, vice president for international studies at the Cato Institute.

Ian Vásquez: And what that led to was, it just pushed coca production to other countries, namely to Colombia. Colombia then became the world’s largest producer of coca.

Radley Balko: This is sometimes called the “balloon effect.” When there’s enough demand for an illicit drug, someone will figure out a way to supply it. So when the U.S. has helped precipitate a crackdown on coca, heroin, or meth production in one country or region, the production just ramps up somewhere else.

Peru and Colombia are neighbors; they share the same ecosystem that’s ideal for growing the coca plant. So when the U.S. squeezed the balloon in Peru, coca production simply moved next door.

Then the U.S. government squeezed the balloon again. In 2000, President Bill Clinton signed the bill funding Plan Colombia, a sweeping anti-drug operation in Latin America.

Ian Vásquez: Plan Colombia spent about $12 billion supported by the United States in fighting the drug war and trying to pacify the country. The United States did not accomplish its primary goal there, but it did spend a lot of money. It did try to repeat that kind of policy in other places with the same kinds of unfortunate results.

Radley Balko: Plan Colombia had two primary goals. The first was to end the armed conflict between the Colombian government and the narcotics-funded guerrilla group known as FARC. The second goal was to crack down on coca growing and the production of cocaine. The U.S. planned do this by giving money, weapons, and strategic assistance to the Colombian government.

Ian Vásquez: When Peru started to crack down, this led to coca production in Colombia. But it didn’t take that many more years until the crackdown in Colombia to lead to an increase in coca production in Peru.

Radley Balko: That back and forth continues to this day, with coca production now spilling into Ecuador as well.

Ian Vásquez: And that’s true with almost every aspect of the drug war. Crop substitution, drug interdiction, eradication. You can see temporary successes — if you want to call it that in the drug war — where you see production in one region go down, but it ends up popping up in another region.

“You can see temporary successes — if you want to call it that in the drug war — where you see production in one region go down, but it ends up popping up in another region.”

Radley Balko: And so despite decades of international drug suppression efforts in individual countries, the overall supply and consumption of cocaine has remained relatively stable. In real dollars, the price per gram of the drug hasn’t changed much since the early 1990s. And to the extent that the cost does fluctuate, it’s driven far more by demand — which drugs come in and out of vogue — than it is by supply.

France24: The first ever global report on the cocaine industry paints a picture of unprecedented growth.

CGTN America: The growth of coca, the leaf used to make the illicit drug, has reached highs not seen in decades.

BBC: Now the United Nations says Colombia has broken its own record for cultivating coca, the main ingredient of cocaine.

Radley Balko: As of 2023, Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia remain the largest cocaine producers on the planet. For 40 years, the United States has unleashed destructive anti-drug policies in Latin America. And for 40 years, those policies have done little to reduce the supply of cocaine.

[

Related

We Need to Reverse the Damage Trump Has Done in Latin America. Biden’s Plans Don’t Cut It.](https://theintercept.com/2020/04/18/trump-latin-america-foreign-policy-joe-biden/)

Crop eradication programs have poisoned farmland with pesticides, often making the soil unusable for years at a time. Those efforts have pushed coca and poppy cultivation into the rainforest, where the farming does yet more environmental damage. Here’s the publication Vice, reporting on that ecological disaster a few years ago.

Vice: It is not just the drug traffickers who are dumping toxic chemicals into the rainforest. Between 1994 and 2015, the Colombian and American militaries sprayed tons of the chemical pesticide glyphosate onto the Amazon in an attempt to destroy coca crops.

Kendra McSweeney: If the government comes along and eradicates your crop, they may be spraying glyphosate, a known carcinogen, on your family, your animals, and your neighbors. So it comes at great risk. But the needs of small farmers is often so great that they’re willing to take that risk for the economic return.

Radley Balko: These fumigation programs use highly concentrated herbicides, which have destroyed other crops, and can drift far afield from their intended targets. Much of this eradication work has been done by private contractors who operate in a legal netherworld, unaccountable to either the U.S. government or the government of the country in which they’re operating.

At the same time, every squish of the balloon disrupts the black markets where turf and market share are established and controlled with violence. So each new disruption means more death and destruction. Vásquez says that due to U.S. wealth, influence, and military might, it has often been difficult for leaders of Latin American countries to say no to these programs.

Ian Vásquez: A lot of the countries that are receiving the United States so-called aid are countries with governments that want the money, that want their politicians to declare that they’re being tough on crime and drug trafficking. And unfortunately, it’s countries like Peru, like Bolivia, or Colombia, or Central American countries that have weak governments in the sense that the institutions are weak there — the rule of law, transparency, accountability.

Radley Balko: But some Latin American countries have been pushing back. In recent years, Bolivia has attempted to reduce U.S. influence by promoting legal coca cultivation. And in 2022, Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro suspended fumigation efforts and other government-enforced eradication of coca. He argued that suppression programs had failed to curb cocaine demand, while having devastating consequences on poor farmers.

In early 2025, speaking at a cabinet meeting, Petro said:

President Gustavo Petro (in Spanish): Cocaine is not worse than whisky. And what hit the United States is fentanyl. It is killing them, and that’s not done in Colombia.

Radley Balko: But like Venezuela, Colombia now faces renewed tensions with the U.S. from the Trump administration. When one of the U.S. military strikes in international waters killed a Colombian man, Petro wrote on social media, “The United States has invaded our national territory, fired a missile to kill a humble fisherman.” Trump responded by calling Petro “an illegal drug leader” and threatened military strikes in that country too.

After the break, how Washington’s counter-narcotic policies in Latin America failed the Bowers family.

[Break]

Radley Balko: Ian Vásquez remembers hearing about the death of Roni and Charity Bowers in 2001. He wasn’t surprised.

Ian Vásquez: Peru in the early 2000s was a country that was transitioning to a more open, more prosperous economy. It still, though, had a lot of problems, like it does today, in terms of weak rule of law. So that when you set up a shootdown policy, you should fully expect that some tragedy is going to happen — and that’s exactly what happened.

Radley Balko: In the days and weeks after the Bowers’ plane went down, Rep. Hoekstra began trying to piece together what went wrong.

Pete Hoekstra: There was a protocol — a protocol that the CIA was supposed to follow — something like seven to nine steps of escalation: identify the plane, verify the tail numbers, reach out, try to establish contact with the plane. If you fail to reach the pilot, to potentially fly next to the missionary plane — kind of wiggle your wings, I guess, which could be interpreted as an international signal to follow the plane.

So there were like seven to nine steps that should have been put in place, should have been conducted before there was any type of activity, aggressive activity, that would result in the potential downing of the plane.

Radley Balko: Part of the confusion was due to the unclear chain of command leading up to the decision to shoot down the plane. The crews of these surveillance teams typically consisted of former military personnel and pilots recruited by the CIA, often working as private contractors. There would also be an officer from the Peruvian military. And in this case, the unarmed surveillance plane was property of the U.S. Air Force.

When the crew on the surveillance plane decided the Bowers’ plane looked suspicious, they alerted the Peruvian Air Force pilot, who was waiting on standby. The U.S. government later claimed that its contractors had no authority and were simply advisers to the Peruvian military. But listening back to recordings of the cockpit chatter, it’s not at all clear exactly who was in charge.

U.S. Pilot 1: OK, I understand this is not our call, but this guy is at 4,500 feet. He is not taking any evasive action. I recommend we follow him. I do not recommend “Phase 3” at this time.

Peruvian Air Force pilot: It’s three phase, authorised, OK?

U.S. Pilot 2: OK. But you sure it’s bandito? Are you sure?

Peruvian Air Force pilot: Yes.

U.S. Pilot 2: It’s bad? OK.

Peruvian Air Force pilot: OK.

U.S. Pilot 2: If you sure.

Radley Balko: Subsequent investigations only underscored just how opaque U.S. overseas drug operations could be. PBS’s Jim Lehrer questioned then-Secretary of State Colin Powell about the program.

Jim Lehrer (PBS NewsHour): Is it a CIA operation?

“Don’t read anything nefarious into the words CIA.”

Colin Powell: A number of government agencies are involved in it. The CIA has the lead on it, and they will be taking all the specific questions on it. But don’t read anything nefarious into the words CIA.

Radley Balko: Powell then defended Operation Air Bridge.

Colin Powell: It was a good, solid program that has been well known. People have known about it. It is not something that is dark and secret. In fact, we have credited this program with helping to reduce drug trafficking coming out of Peru, so it’s a successful program that has had this tragedy now associated with it, and we’ve got to review the entire program.

Radley Balko: Less than two weeks after the Bowers’ plane went down, a House Oversight Committee held hearings on the incident that aired on C-SPAN.

Mark Souder: The Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy, and Human Resources is now called to order.

Radley Balko: That’s Rep. Mark Souder, a Republican from Indiana and the chair of the subcommittee that held the hearing.

Mark Souder: Just a little over a week ago, a terrible tragedy occurred that broke the heart of every American when, through a preventable mistake, a missionary, whose life had been committed to serving others on behalf of God, was killed, along with her little girl.

Radley Balko: By 2001, the crack epidemic was finally on the wane, along with the violence that came with it. The U.S. had begun what would be a historic 25-year drop in crime. But those trends were not yet apparent. So for many, the urgency of eradicating illicit drugs was still as apparent as ever.

Souder himself was one of the most enthusiastic supporters of a restrictive, militaristic drug policy. That even he was bothered by the shootdown of the Bowers’ plane — that even staunch, drug war Republicans were demanding answers — that was a big deal.

Mark Souder: From a public policy standpoint, where is the United States government to head? What will the United States’ anti-drug efforts in South America be after the Peru incident?

Radley Balko: The Bush administration first tried to blame the Peruvian military for the Bowers’ deaths. But the media, some members of Congress, and outside experts pushed back on the official government position. At the time, that was pretty rare with respect to the drug war.

Here’s Adam Isacson from the Center for International Policy, testifying before Souder’s committee.

Adam Isacson: While the Peruvian pilot pulled the trigger, he pulled the trigger of a gun provided by the United States while flying a plane provided by the United States. He was trained in these operations by the United States, and he was alerted to his target by intelligence provided by the United States.

Radley Balko: Up to that point, the Air Bridge Denial Program had enjoyed bipartisan support, as did most U.S. anti-drug policies in Latin America. And Plan Colombia had of course been signed and championed by President Clinton. But at least some congressional Democrats, like Jan Schakowsky and Elijah Cummings, lambasted the operation.

Rep. Jan Schakowsky: The kind of action we saw in Peru last week amounts to an extrajudicial killing, and we in this country now have innocent blood on our hands because of it.

“It goes against one of our most sacred, due process principles; namely, that all persons are presumed innocent until proven guilty.”

Rep. Elijah Cummings: The Peruvian shootdown policy would never be permitted as a domestic United States policy precisely because it goes against one of our most sacred, due process principles; namely, that all persons are presumed innocent until proven guilty.

Rep. Jan Schakowsky: The U.S. taxpayers are unwittingly funding a private war with private soldiers. This is a shoot-first-and-ask-questions-later policy encouraged by the United States in its war on drugs.

Rep. Elijah Cummings: Certainly Veronica and Charity Bowers are not the first innocent victims of the war on drugs. Is a policy that also sacrifices core American values a prudent and acceptable course to follow?

Radley Balko: In one particularly telling moment**,** Rep. Cummings asked John Crow, who led the State Department’s narcotics efforts in Latin America, how many planes had been shot down through the Air Bridge Denial Program. It was an entirely reasonable question: How many times had the U.S. pressured foreign governments to shoot down civilian aircraft based on nothing more than mere suspicion of drug running?

And yet Crow couldn’t answer.

How many times had the U.S. pressured foreign governments to shoot down civilian aircraft based on nothing more than mere suspicion of drug running?

Elijah Cummings: Can somebody tell me how many airplanes have been shot down since 1995? … Shootdowns and force-downs?

John Crow: … We were not able to come up with one, or agree on the same figure. … Our figures would show that starting in 1995, aircraft were not all shot down, some forced down, but through a combination, a figure of some 50 aircraft — and that is not precise.

Elijah Cummings: … Why can’t you tell me that? … We are talking about shooting down people.

John Crow: Yeah.

Elijah Cummings: Like, dead. I mean, we are talking about using — I mean, this is some serious stuff. I am trying to figure out, if I was just a regular citizen just sitting here looking at this, and I’ve got some of my top-flight people in the drug war talking about they don’t know how many shootdowns or force-downs, I would be a little bit concerned about what’s going on.

Radley Balko: Cummings’s frustrations back then seem almost prescient today, as the Trump administration continues to elude questions about its own killings off the South American coast.

Still, this is the drug war. And so it didn’t take long for a reliable foot soldier like Souder to retreat to familiar territory.

Mark Souder: Unfortunately, many people in America are becoming convinced — falsely — that the war on drugs has not worked.

Radley Balko: Souder then deployed the sort of hyperbole and demagoguery that had long defined U.S. drug policy.

Mark Souder: And what is the alternative of those who oppose the war on drugs? Having more weed-wacked, meth-wasted, heroin-junkie crackheads driving a car headed in your direction or prowling your neighborhood? Or, perhaps even more painfully, coming home to beat you or your child? The facts are simple. When this country focuses on the war on drugs, we make progress.

Radley Balko: Rep. Schakowsky responded with a laundry list of reasons why the status quo was not working.

Jan Schakowsky: I know some of those with us today would like to put this tragedy behind us and get back to the business of the drug war. However, there are so many questionable aspects of our policy and so many unanswered questions.

Why do we have to hire private contractors to do our work in Andean countries? How much of the public’s money has been spent to hire what some have referred to as mercenaries? Where is the accountability? Who exactly are they? Do they even speak Spanish?

From what I do know, outsourcing in the Andean region is a way to avoid congressional oversight and public scrutiny. The use of private military contractors risks drawing the U.S. into regional conflicts and civil war. It is clear to me that this practice must stop.

Radley Balko: Rep. Hoekstra took a subtler tone. He wasn’t interested in overhauling the war on drugs. But because the victims were his constituents, he focused instead on the need for some level of transparency.

Rep. Pete Hoekstra (at Oversight Committee hearing): The families and the American people deserve to know how this happened. I know there are certain pieces of this complex puzzle that we will never be able to explain, but there should be no part that we keep hidden.

“It was pretty clear that there were people inside the agency that were ready to cover this up from day one.”

Pete Hoekstra: And so it was pretty clear that there were people inside the agency that were ready to cover this up from day one.

Radley Balko: Looking back on that time, Hoekstra says that the government agencies involved slow-walked the investigative process.

Pete Hoekstra: Because the information, especially the information going out to the public, was so different from what actually happened, it provided cover for people to reimplement this flawed program.

Radley Balko: So the government agencies involved avoided accountability and there would be no substantial change in policy. The CIA’s inspector general report on the incident was published in 2008, but it wouldn’t be fully declassified until 2010. When it finally was made public, the details were damning.

Brian Ross (ABC News): Today, the CIA was accused of an almost 9 year long campaign to mislead and stonewall Congress and others about how and why the rules were broken.

Pete Hoekstra (at Oversight Committee hearing): If there’s ever an example of justice delayed, justice denied, this is it.

Brian Ross (ABC News): The CIA insists the entire episode was handled thoroughly and professionally and that there was no cover-up — to the outrage of the dead woman’s parents.

Gloria Luttig (Veronica Bowers’s mother): I want somebody to tell me why they killed my girl.

Pete Hoekstra: Those of us on the committee and I think a number of members of Congress knew exactly what happened. The CIA knew exactly what happened. The Justice Department should have known exactly what happened. They would have had access to the tapes and those types of things. And the calculus at some point in time that is made by the Justice Department, by the intelligence community, and by the administration at that point is, this program is more important than focusing or rehashing the mistakes that were made.

“This program is more important than focusing or rehashing the mistakes that were made.”

Radley Balko: The CIA inspector general tallied 15 incidents in which a plane had been shot down through the program between 1995 and 2001. The watchdog found violations of required procedures in all 15 incidents. In some cases, suspected aircraft were shot down within minutes of being sighted by the Peruvian fighter, without being properly identified, given required warnings, or given time to respond. Another congressional committee estimated that there could have been many more planes shot out of the sky — as many as 50.

More disturbing still, the report concluded that “CIA officers knew of and condoned most of these violations, fostering an environment of negligence and disregard for procedures designed to protect against the loss of innocent life that culminated in the downing of the missionary plane.”

Brian Ross (ABC News): Today the CIA said its nine-year long investigation had determined that 16 CIA employees should be disciplined, including, we learned, the woman then in charge of counternarcotics. Many of the 16 are no longer with the CIA, and one of them told us his discipline was no more than a letter of reprimand placed in his file, which he was told would be removed in one year. That’s the punishment for his role in the wrongful deaths of two innocent Americans, Diane.

Diane Sawyer: After nine years.

Brian Ross: Yes, after nine years.

Diane Sawyer: OK, thanks Brian.

Pete Hoekstra: Even after nine years, I’d say there was never really a full accountability to the individual or the organizations that precipitated these events. I’m worried that there were more. That the Bowers family is not the only family, or the only Americans, or the only innocent people that were impacted. Were there other Peruvians, were there other innocent individuals that might have been killed through this process? I don’t know the answer, but I suspect that the answer would probably be yes.

Ian Vásquez: I think that a lot of times when people talk about the war on drugs, they think about going after the bad guys, the criminals who are ruthless, the mafia guys, the cartel guys, the people who are breaking the law knowingly.

[Content truncated due to length…]

From The Intercept via this RSS feed