.PhotoQuoteCenter { text-align: center; } .PhotoQuoteCenter_text { color: #868686; text-align: center; font-family: var(–font-eukraine); font-size: 14px; font-weight: 400; line-height: 20px; margin-bottom: 20px; } .PhotoQuoteCenter_img, .PhotoQuoteCenter img { width: 100%; max-width: 200px; margin: 0 auto; }

Created in partnership with KPMG Ukraine Gateway

It’s a scene all too familiar for those who frequent the Ukraine conference circuit: People gather from all over the world, talk big about pouring capital into the war-torn country, and leave, with few plans for actual investment.

Ukraine’s resistance to Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022 drew unprecedented attention to the eastern European nation. Everyone from Wall Street to Main Street wanted to be part of the rebuilding.

As it became clear that the war would not end any time soon, the hype around reconstruction quickly evaporated. Since then, many foreign investors have preferred to stay on the sidelines, attending conferences while waiting to come after the war ends.

But there are those who have invested and found success, undeterred by the risks and idiosyncrasies of doing business in wartime Ukraine. A wave of mostly undisclosed deals in the fast-growing defense tech sector has opened new ground for investors, while transactions like French billionaire Xavier Niel’s telecom acquisition have been historic in terms of deal size for the market.

New entrants may be scarce, but existing foreign investors have poured tens of millions of dollars into new projects since 2022.

What these investors share is a pragmatic awareness of Ukraine’s business realities: a market that is dynamic and rapidly evolving, eager for investment and development, yet that requires patience as it works through its growing pains and the difficulties of war.

“Investing in Ukraine in 2025 requires a pragmatic, long-term approach — the market won’t suit every investor, but those prepared to engage early, work with reliable local partners, and incorporate appropriate risk-mitigation, may find significant upside,” says Svitlana Shcherbatyuk, a partner at KPMG in Ukraine who leads transaction services in deal advisory.

“For investors who can balance discipline with vision, Ukraine may become one of the most consequential investment stories of the coming decade.”

They also understand that they must be prepared to bring patient capital to Ukraine, and not only because they can’t get it out due to capital controls. Putting money to work in the country right now is less of a get-rich-quick scheme than it is a long-term investment in the future of their company, as well as Ukraine.

“While business growth and paying employees remain their main priorities, the chance to support Ukraine and its people also motivates them to think long-term,” says Yuriy Katser, partner and head of legal services at KPMG Law Ukraine, who has broad experience in international tax and legal matters.

“They know they are on the right side of history.”

And for those who are still hesitant, afraid to cross the border into Ukraine, the message from the investment community is clear: invest in Ukraine now, or risk losing out when the war ends.

“If you start investing in Ukraine or working with Ukrainians after the war ends, you will be too late because there will be others who will have already taken your place,” says Anna Pogrebna, a seasoned legal professional with experience in international and cross-border transactions.

And while some wait, there’s reason to believe others are already here, shopping around.

“There’s a quiet new trend in Ukraine — of companies increasingly coming and sniffing around, especially in defense, real estate, and public-private partnership projects,” said Alex Frishberg, a Kyiv-based legal expert with over three decades of professional practice. While not many deals have actually been inked, “the groundwork is being laid,” he says.

And it’s a buyer’s market, says Frishberg. Ukraine’s assets aren’t the cheapest frontier-market bargains, but prices are still favorable for investors at the moment.

“While some investors hesitate or try to squeeze harder, those who move now can buy at roughly three times annual earnings instead of the usual ten or twelve,” according to Frishberg.

Meanwhile, doing business in Ukraine has become easier thanks to pro-investor reforms, including deregulation, digitalized permitting and licensing, a wartime moratorium on many state inspections, as well as strong international financing for eligible companies, says Katser.

And when the war does end, a large-scale effort to rebuild Ukraine — already estimated at around $480 billion — can be expected.

“If you add $500 billion onto a $200 billion economy, something’s going to happen here,” says Swen Lorenz, a real estate investor currently entering the Ukrainian market.

The Kyiv Independent spoke with a dozen investors, consultants, lawyers, and entrepreneurs to produce a series of guides on investing in wartime Ukraine in partnership with KPMG Ukraine Gateway.

For this first of 10 guides, the Kyiv Independent is presenting 10 key insights for anyone considering — or who has already made — investments in the country, drawn from those conversations. This list is not exhaustive or comprehensive, but is meant to help you make informed decisions, and is presented without sugarcoating.

10 things you may not have considered about investing in Ukraine

1. No, Ukraine has not been reduced to rubble.

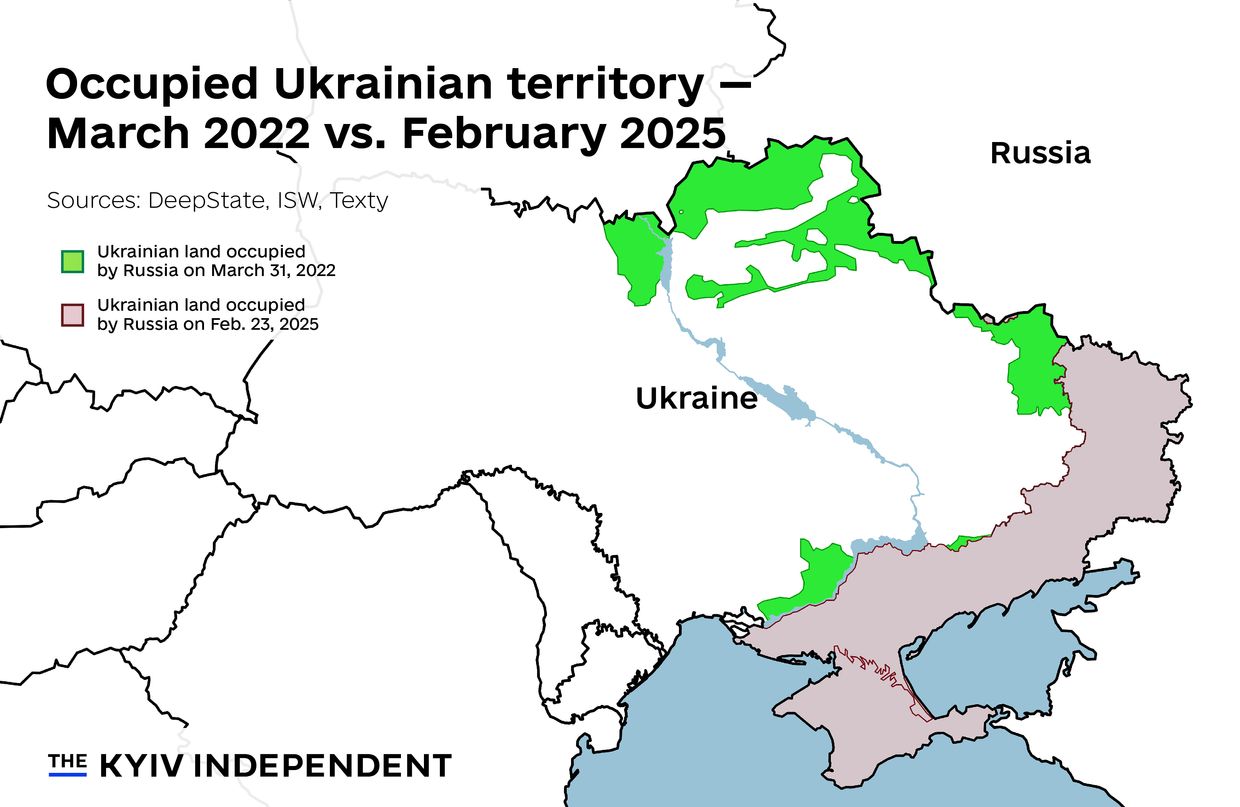

This may seem painfully obvious to experienced investors, but for those who have never visited Ukraine and only follow news reports of the war, it can be surprising that much of the country is far from the front lines and relatively safe and untouched by the war. Ukraine, the largest country entirely in Europe, stretches 1,200 kilometers east to west. The fiercest fighting is in the far east and southeast. Western and central Ukraine (including Kyiv) and parts of southern oblasts like Mykolaiv and Odesa remain relatively safe for business. Despite the war and the damage it has caused to parts of the country and the economy, key institutions remain functional.

A comparison of occupied Ukrainian territory, at its peak in March 2022, versus February 2025. (Nizar al-Rifai/The Kyiv Independent)

2. Investing in Ukraine requires deep pockets filled with private and patient capital.

Bank financing is extremely limited for Ukraine-related investments, particularly for small- and mid-sized projects. Many banks outside Ukraine won’t even open accounts for capital headed to the war-torn country. Programs through international financial institutions exist, but they target large projects like massive infrastructure, leaving small- and mid-sized investors mostly shut out. As a result, serious investors need to commit private capital — either their own or funds raised from wealthy individuals and family offices. Even for projects eligible for debt financing, expect to put 30–40% upfront.

3. You basically can’t freely move your money out of Ukraine while martial law is in effect.

Necessary, but unpopular capital controls introduced by Ukraine’s central bank at the start of the full-scale invasion have largely restricted the repatriation of investments, creating understandable concern for foreign investors. While it’s not entirely true that transfers are completely banned, the reality is that they are limited. Since 2023, the National Bank of Ukraine has permitted some monthly transfers of dividends abroad, as well as the ability to pay loans, leases, and rents abroad, but in practice, moving significant capital out of the country can still be challenging. Due to these restrictions, exit strategies require careful planning. Structuring via foreign jurisdictions is possible, but in most cases, the most practical path for cashing out is foreign-to-foreign sales.

4. War risk insurance is available, but it is extremely limited.

Talk to most investors and they’ll roll their eyes at the mention of war risk insurance — frequently touted, rarely used, it’s become something of an annoyance. The reality is that war risk insurance exists, but it’s expensive and generally aimed at larger investments. Big infrastructure projects can be covered through international programs, and countries like Germany and the U.S. offer substantial coverage via their development agencies. Smaller investments may get some protection through local insurers or the Ukrainian export agency. But medium-sized investors — where many fall — often won’t find adequate coverage and need to be comfortable operating without it.

5. Investing is cheaper in Ukraine right now — but it’s not your typical frontier market.

Some investors expect bargains due to the war but often face sticker shock. While prices are currently lower than in peacetime — roughly a third of usual valuations — many companies, especially the top ones, know their value and command strong prices. While they may be willing to sell, it’s likely to be at a relatively high price. Investors looking for a company to acquire in Ukraine at a significant discount are in for a surprise.

6. Corruption in Ukraine exists, but it’s not what you think.

Corruption exists, but it’s unlikely to be as widespread as many foreign investors may believe when they come to Ukraine. No, you won’t walk out of the house and be confronted with paying a bribe. Caution should be exercised. Especially when looking for local partners and when working with the government. Experienced investors might even tell you to avoid the government tender process altogether, unless you can ensure the due diligence will be thorough.

Despite the headline-making corruption scandals, Ukraine has made progress in rooting out corruption. Its digitalization efforts, especially in real estate and construction, have made state registries transparent and easy for lawyers to access. Corruption in notary services has decreased. Many people don’t realize that the country is a leader in digital government services, with asset information, public services, and applications for permits fully digital.

7. Doing business in Ukraine requires patience and understanding of practices rooted in the country’s young and tumultuous history.

You may or may not know that doing business in the Soviet Union was illegal — derisively referred to as “commerce.” Ukraine’s business environment, then, still only in its mid-30s, has developed its own quirks that can surprise or even confuse foreigners entering the market. Foreign investors, particularly those from the West, need patience and cultural awareness when operating in Ukraine, a developing country that has been at war for the past decade. Differences in business planning or paperwork are sometimes mistaken for incompetence or corruption when that’s not the case.

This can play out in how disputes are handled. While foreign businesspeople may expect to rely on the courts, Ukrainian businesspeople — distrustful of an overly bureaucratic, at times inefficient court system — may opt for private conflict resolution first, which outsiders may view as an attempt to skirt the justice system.

8. Ukrainians can be very direct in their approach to deal-making.

The direct approach to doing business can baffle outsiders, particularly Western businesspeople who might experience the bluntness as rude. One interesting way this shows up is in how Ukrainian businesspeople may perceive an offer of a joint venture, for example. While the practice of going into joint ventures may be familiar to Western businesspeople, a Ukrainian businessperson may approach them cautiously, wanting to see up front what the real added value would be — whether it would be equipment, technology, know-how, or a real cash contribution.

9. Finding a local partner can take time, but it is an absolutely critical part of doing business in Ukraine.

Most foreigners who have been doing business in Ukraine long enough will have a story, or two, about a local partner they regret going into business with. Finding a trustworthy partner in the country to go into business with can be a daunting task, which is why consultants with a presence and good reputation in Ukraine are often essential for navigating connections, projects, and meetings. You don’t have to be in Ukraine to find a reputable consultant who can do some of the initial legwork for you, but doing business in the country will require developing strong personal relationships there.

10. You will have a very hard time understanding how to do business in Ukraine if you don’t come here.

If an investor tries to understand Ukraine from afar, they will have a hard time making any informed decisions. The country, already covered by the fog of war, can seem opaque to outsiders. Cultural nuances and local insights matter everywhere, especially when entering a new market, but in Ukraine’s case, a sense of the “unknown” comes from two sides: the country has mainly come into global focus after the full-scale invasion, and there are long-standing misconceptions shaped by years of Russian propaganda. It takes time to adapt — and to see beyond those distortions to fully appreciate what Ukraine has to offer. But those who come are often struck by the country’s beauty, its rapid development even in wartime, the Ukrainians’ work ethic, and the opportunities waiting for those who know where to look.

From The Kyiv Independent - News from Ukraine, Eastern Europe via this RSS feed