This editorial by Ignacio Ramonet originally appeared in the November 25, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper.

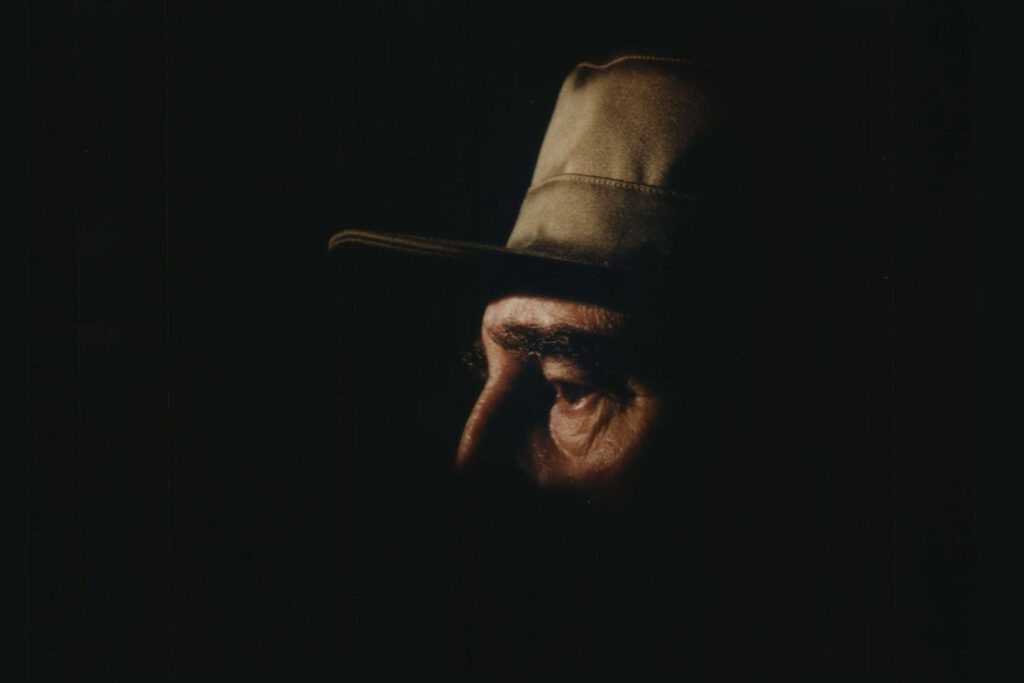

In the world pantheon dedicated to those who fought most diligently for social justice and who showed the most solidarity in favor of the oppressed of the Earth, Fidel Castro – whether his detractors like it or not – has a prime place reserved.

I met him in 1975 and spoke with him on numerous occasions, but for a long time, always in very professional and specific circumstances, such as when I was reporting on the island or participating in a congress, seminar, or other event. Later, our relationship grew closer. Sometimes he would invite me to dinner in the privacy of his office at the Palace of the Revolution, and we would chat for hours about world affairs. Other times, he entrusted me with discreet “missions,” such as meeting with a Latin American leftist leader about whom he had his doubts, so that I could give him my personal opinion. He was the first to speak highly of Hugo Chávez (who was then viewed with suspicion by much of the world’s left because he was accused of having led, on February 4, 1992, an attempted coup against Carlos Andrés Pérez, the social-democratic president of Venezuela and leader of the Socialist International). Fidel advised me to go and see him, to get to know him, and to help him.

Ignacio Ramonet & Fidel Castro

When, in 2003, we decided to write the book One Hundred Hours with Fidel, he invited me to accompany him for weeks on various trips. Both in Cuba (Santiago, Holguín, Havana) and abroad (Ecuador). By car, by plane, on foot, over lunch or dinner, we talked at length. With and without a recorder. About every possible topic: the day’s news, his past experiences, and his present concerns. I would later reconstruct these conversations from memory in my notebooks. Then, for three years, from 2003 to 2006, we met very frequently, at least for several days at a time, once a quarter, to make progress on the book.

I thus discovered an intimate Fidel. Almost shy. Very polite. Listening attentively to each person he spoke with. Always attentive to others, and particularly to his collaborators. I never heard him raise his voice. Never gave an order. With manners and gestures of old-fashioned courtesy. A true gentleman. With a strong sense of honor. Who lives, from what I could see, in a spartan manner. Austere furnishings, healthy and frugal food. The lifestyle of a soldier-monk.

His workday usually ended at five or six in the morning, just as day was breaking. More than once he interrupted our conversation at two or three in the morning because he still had to attend some “important meetings”… He slept only about four hours; plus, occasionally, an hour or two at any time of day.

But he was also an early riser. And tireless. Trips, journeys, meetings followed one after another without respite. At an unprecedented pace. His assistants—all young and brilliant, around 30 years old—were, by the end of the day, exhausted. They fell asleep standing up. Exhausted. Unable to keep up with this tireless giant. Fidel demanded notes, reports, cables, news, statistics, summaries of television or radio broadcasts, phone calls… He never stopped thinking, pondering. Always alert, always in action, always at the head of a small general staff—comprised of his assistants and aides—fighting one battle after another. Always full of ideas. Thinking the unthinkable. Imagining the unimaginable. With an unprecedented, spectacular mental audacity.

Once a project was defined, no material obstacle could stop it. Its execution was obvious, a given. “The logistics will continue,” Napoleon would say. Fidel would say the same. His enthusiasm drew in collective support. He stirred people’s wills. As if by magic, ideas materialized, becoming tangible facts, realities, events.

His rhetorical skill, so often described, was prodigious. Phenomenal. I’m not talking about his well-known public speeches, but about a simple dinner table conversation. Fidel was a torrent of words, an avalanche, a waterfall, which he accompanied with the prodigious gestures of his delicate hands.

He liked precision, exactness, punctuality. With him, there was no room for approximations. A prodigious memory, of unusual precision. Overwhelming. So rich that it sometimes seemed to prevent him from thinking synthetically. His thinking was branching. Everything was linked. Everything was connected to everything else. Constant digressions. Permanent parentheses. The development of a topic would lead him, by association, by recalling a certain detail, a certain situation, or a certain character, to evoke a parallel topic, and another, and another, and another. Thus moving away from the central theme. To such an extent that his interlocutor feared, for a moment, that he had lost the thread. But then he would retrace his steps and return, with surprising ease, to the central theme, the main idea.

At no point, during more than a hundred hours of conversations, did Fidel place any limits on the topics to be addressed. As the intellectual he was, and of impressive caliber, he did not fear debate. On the contrary, he demanded it, he encouraged it. Always ready to argue with anyone. With great respect for the other person. With great care. And he was a formidable debater and polemicist. With arguments galore. He was only repulsed by bad faith and hatred.

Few men have known the glory of entering legend and history while still alive. Fidel is one of them. He belonged to that generation of mythical insurgents who, pursuing an ideal of justice, launched themselves into political action in the 1950s with the ambition and hope of changing a world of inequality and discrimination, marked by the beginning of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States.

At that time, in more than half the world—in Vietnam, Algeria, Guinea-Bissau—oppressed peoples were rising up. Humanity was still, for the most part, subjected to the infamy of colonization. Almost all of Africa, parts of the Caribbean, and a good portion of Asia were still dominated and subjugated by the old Western empires. Meanwhile, the nations of Latin America, theoretically independent for a century and a half, remained subject to social and ethnic discrimination, exploited by privileged minorities, and often marked by brutal dictatorships, supported by Washington.

Fidel withstood the onslaught of no fewer than ten US presidents (Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, Bush Sr., Clinton, and Bush Jr.). He had political relationships with the principal leaders who shaped the world after World War II (Mao Zedong, Nehru, Nasser, Tito, Ho Chi Minh, Kim Il-sung, Khrushchev, Olaf Palme, Ben Bella, Boumedienne, Arafat, Indira Gandhi, Salvador Allende, Brezhnev, Gorbachev, François Mitterrand, John Paul II, etc.). And he personally knew some of the leading intellectuals and artists of his time (Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Arthur Miller, Pablo Neruda, Jorge Amado, Rafael Alberti, Guayasamín, Cartier-Bresson, José Saramago, Gabriel García Márquez, Eduardo Galeano, Noam Chomsky, etc.).

Under his leadership, his small country (100,000 km², 11 million inhabitants) was able to pursue a great power policy on a global scale, even challenging the United States, whose leaders were unable to overthrow him, eliminate him, or even alter the course of the Cuban Revolution. And finally, in December 2014, they had to admit the failure of their anti-Cuban policies, their diplomatic defeat, and begin a process of normalization that entailed respect for the Cuban political system.

In October 1962, World War III nearly broke out due to the US government’s protest against the installation of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba. Their primary purpose was to prevent another military landing like the Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961, or any other direct attack by US armed forces to overthrow the Cuban Revolution.

For more than sixty years, Washington (despite the reestablishment of diplomatic relations) has imposed a devastating economic, commercial, and financial blockade on Cuba (reinforced by the 243 measures adopted during Donald Trump’s first term), with tragic consequences for the island’s inhabitants. Washington also continues to wage a permanent ideological and media war against Havana through social media, flooding Cuba with hostile propaganda reminiscent of the worst days of the Cold War.

Furthermore, for decades, several terrorist organizations—Alpha 66 and Omega 7—opposed to Cuba, were based in Florida, where they maintained training camps and regularly dispatched armed commandos, with the complicity of U.S. authorities, to carry out attacks. Cuba is one of the countries that has suffered the most from terrorism (approximately 3,500 deaths) over the past sixty years.

Faced with such constant attacks, the Cuban authorities have advocated unwavering unity within the country. And they have applied, in their own way, the old Jesuit motto of Ignatius of Loyola: “In a besieged fortress, all dissent is treason.” But there was never—Fidel explicitly forbade it—any cult of personality. No official portrait, no statue, no stamp, no currency, no street, no building, no monument bearing the name or likeness of Fidel, or of any of the living leaders of the Revolution.

A small country deeply attached to its sovereignty, Cuba, under the leadership of Fidel Castro, despite constant external harassment, achieved exceptional results in human development: the abolition of racism, the emancipation of women, the eradication of illiteracy, universal vaccination, a drastic reduction in infant mortality, and a rise in the general cultural level. In education, health, medical research, culture, and sports, Cuba has reached levels that place it among the most efficient nations.

Its diplomacy remains one of the most active in the world. In the 1960s and 1970s, Havana supported guerrilla movements in many Central American countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua) and South American countries (Colombia, Venezuela, Bolivia, Argentina). Cuban armed forces participated in large-scale military campaigns, particularly the wars in Ethiopia and Angola. Its intervention in Angola fifty years ago resulted in the defeat of the elite divisions of the South African Republic, which undeniably accelerated the fall of the racist apartheid regime and facilitated the independence of Angola and Namibia.

The Cuban Revolution, of which Fidel Castro was the inspiration, theorist, and political and military leader, remains today, thanks to its successes and despite its shortcomings, an important reference point for millions of the world’s dispossessed. Here and there, in Latin America and in other parts of the world, women and men protest, fight, and sometimes die trying to establish systems inspired by the Cuban model.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the disappearance of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the historic failure of state socialism and the centrally planned economic model in Eastern Europe did not alter Fidel Castro’s dream of building a new type of society in Cuba: decolonized, fairer, healthier, more egalitarian, more feminist, more ecological, better educated, without discrimination of any kind, and with a total global culture.

Until the day before his death on November 25, 2016, at the age of 90, he remained active in the defense of the environment, against climate change and neoliberal globalization. He was still in the trenches, on the front lines, leading the fight for the ideas he believed in, ideas that nothing and no one could ever make him renounce.

On the Ninth Anniversary of Comandante Fidel Castro’s Passing

November 25, 2025

Until the day of his death, Fidel was still in the trenches, on the front lines, leading the fight for the ideas he believed in, ideas that nothing and no one could ever make him renounce.

People’s Mañanera November 25

November 25, 2025

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on International Day of the Elmination of Violence Against Women, sexual abuse legislation, commitments to women’s rights, farmers blockades, and the new water law.

On the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women

November 25, 2025November 25, 2025

It is the state’s responsibility to implement the actions required to build a country without violence, where respect, constructive coexistence, & recognition of the value of women and their contribution to the social, economic, & political life of Mexico prevail.

The post On the Ninth Anniversary of Comandante Fidel Castro’s Passing appeared first on Mexico Solidarity Media.

From Mexico Solidarity Media via this RSS feed