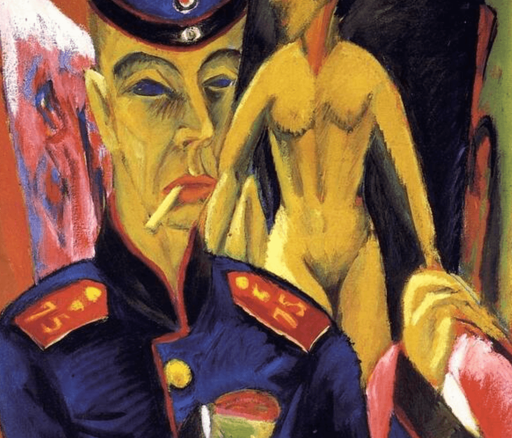

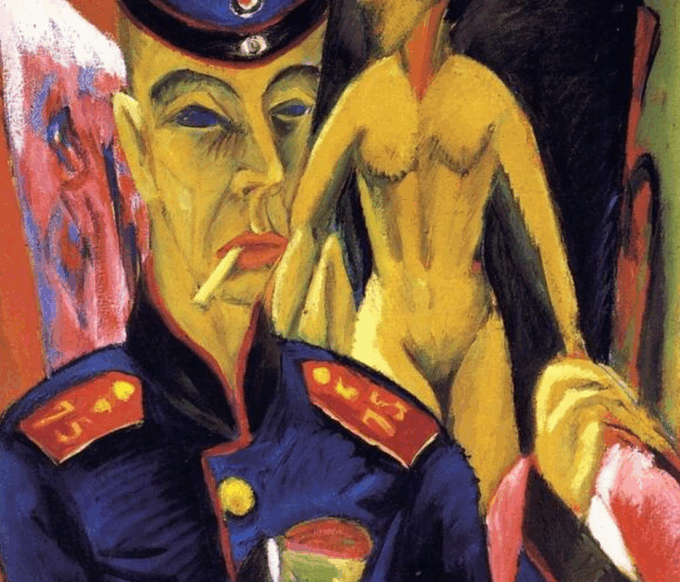

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) Self-Portrait as a Soldier, 1915. Oil on canvas. Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH. Charles F. Olney Fund

In 1938, the great art historian E. H. Gombrich, working with Ernst Kris, who was a psychoanalyst, published an essay, “The Principles of Caricature.” At that time, Gombrich had just arrived in England, a refugee from National Socialism. And he was interested in the history of caricature, which involves manipulating portraits with aggressive intent. The two scholars were interested in the fact that these distorted images appear late in the history of figurative European art, at the end of the sixteenth century.

Why, they asked, do we get pleasure from such imagery? Here, under the spell of Sigmund Freud’s account of jokes, they were concerned to understand the psychic function of caricature. When we hear a successful joke, we laugh- and when we see an effective caricature, we are pleased. But what explains that success? Following Freud, Gombrich and Kris offer a theory of caricature, with reference to examples by Bernini and other artists. These distorted images, like the word play in many of Freud’s examples of jokes, give pleasure because they show a mastery of aggression. And this leads them to consider a famous nineteenth-century political example, Louis-Philippe, the Roi Bourgeois (1830-48), the French citizen king, shown as a pear. Expressing a hostile thought in this permitted form, the caricature inspires us to laugh. By illustrating how the king could be seen as a pear, his political views are critically rejected.

In “the horror of bearing arms: Kirchner’s self-portrait as a soldier, the military mystique and the crisis of world war I (with a slip-of-the-pen by Freud)” an essay published in Art forum in 1980 Joseph Masheck took up these ideas. He offers an elaborate discussion of a famous Ernst Kirchner painting, which shows him mutilated with one arm lost. (Masheck was editor of the journal.) And he illustrates it with an example from Freud, a female terra cotta sculpture, the mythic Baubo, who overcame the intractable mourning of Demeter “by lifting up her skirt and exposing her sex, which made Demeter laugh.”

Here, then, in a literal way Kirchner’s castration- anxiety, in which he (imagined) losing a hand in war, because this scene of laughter produced by Baubo’s female exhibitionism. This, Masheck concludes, “is an image of the mortal terror of war felt from deep within the self, yet one which manifests itself in a brutal, almost Brechtian objectification that makes pressing moral demands on the spectator.” The humor experienced by Demeter is translated into the terror produced by Kirchner’s painting. Masheck’s essay is a beautiful illustration of the theorizing by Kris and Gombrich.

Visual aggression, female bodies, caricature: Familiar as I am with these themes in an academic context, I never imagined that they would play any role in a political context. Until today! What a strange world we live in.

Note: The essays by Kris/Gombrich and Masheck are online with full illustrations.

The post Presidential Caricature appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed