Gallery of The Old Bedford [Music Hall] by Walter Sickert

Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital. In The Times this week I wrote about why democracies need elites.

Thanks for reading Cultural Capital! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

**Are you behaving like an AI?**I think Ian Leslie is one of the small handful of people who writes interestingly about AI. Last week he wrote a delightful and imaginative piece about the ways human beings can come to resemble Large Language Models.

I liked this point in particular. AI engineers refer to the phenomenon of “model collapse”. The idea is that as tech companies run out of human-created text and images to train their machines on they will increasingly have to feed them with AI-generated outputs instead. But as AI content tends to be predictable and generic this creates a feedback loop by which “each new iteration of the model inherits the biases and errors of the previous one” and accentuates them, creating more and more generic and repetitive content each time.

Ian’s idea is that something similar happens to humans as they get older:

“Humans collapse during their course of their lives.” We, too, learn patterns in the data of experience on which we then become over-dependent, favouring the model in our heads over the flux of reality. As we get older, we become rigid in our thinking, set in our ways. We talk to the same friends and use the same information sources. We return to the same old thoughts and say the same old stuff.

And so we suffer AI-style model collapse and become boring, repetitive and generic. The solution is to make sure your training data is fresh by seeking out new experiences and high quality information:

We should expose ourselves to novelty, privileging new art (or at least, art that is new to us), and people from outside our usual circles. We should look for contrarian perspectives from people who really know what they’re talking about.

The obvious solution of course is to subscribe to Cultural Capital.

Love and deathI’m a longtime fan of the brilliant series of poetry analysis podcasts Close Readings hosted by Mark Ford and Seamus Perry. For me it’s up there with The Rest is History.

Last week I mainlined the latest series of Close Readings which is titled “Love and Death” and looks at poetic elegies. You have to subscribe to hear whole episodes which is a bit fiddly to do but worth it. Listening through the archive is a pretty comprehensive introduction to English poetry since the mid-nineteenth century.

The latest series is pure pleasure, covering elegies by WH Auden, Matthew Arnold, Sylvia Plath and more. I love how much Ford and Perry obviously love and care about poetry as well as knowing about things like historical context and rhyme schemes.

The best episodes of the current series are probably the ones on Thomas Gray’s Elegy in a Country Churchyard, Milton’s Lycidas and Auden’s In Memory of WB Yeats. My very favourite episode so far is the one on Thomas Hardy’s poems written after the death of his wife Emma.

You can watch a bit of the Thomas Gray episode on YouTube here:

Populism as a style of cognitionIn his book Thinking Fast and Slow Daniel Kahneman draws a famous distinction between two major styles of human cognition, “fast” intuitive thinking and “slow” analytic thinking.

In this interesting piece, Joseph Heath draws on Kahneman’s idea to argue that populism is less a political ideology than a politics that appeals to a particular kind of cognitive strategy: fast, commonsensical intuitive thinking, as opposed to the slow, analytic, often counterintuitive thinking associated with the educated “cognitive” elite. What is going on with populism is that:

People are not rebelling against economic elites, but rather against cognitive elites. Narrowly construed, [populism] is a rebellion against executive function. More generally, it is a rebellion against modern society, which requires the ceaseless exercise of cognitive inhibition and control, in order to evade exploitation, marginalization, addiction, and stigma. Elites have basically rigged all of society so that, increasingly, one must deploy the cognitive skills possessed by elites to successfully navigate the social world. (Try opening a bank account, renting an apartment, or obtaining a tax refund, without engaging in analytical processing.)

Of course, as Heath says, analytic thinking isn’t always the best way to approach a problem. Sometimes our “common sense” intuitions are right.

Cinema addictionThis is a really great piece by Leo Robson on his adolescent cinema addiction. The first paragraph could be the opening of a comic novel:

During a four or five-year period at the turn of the millennium, I went to the cinema around six hundred times — or, I should say, I saw around six hundred films at the cinema, since many of the visits were for double, triple and occasionally quadruple bills. I wasn’t a film critic or festival programmer or even an aspiring director. I was just an adolescent schoolboy and, in my parents’ probably loving description, a ‘weirdo’.

It’s also a wonderful account of the way that when you are in your teens you can just immerse yourself in new information and soak it up:

At some point I wrote a fan letter to [the film critic] David Thomson. In his reply, he urged me to develop interests other than film. That was Spielberg’s problem, Thomson said – he didn’t know anything else. But there seemed little danger of that in my case. (Not that it was really true of Spielberg.) Films were always telling you about other things. In 1998 alone there were adaptations of Les Misérables, The Woodlanders, Great Expectations, Lolita, Washington Square, Mrs Dalloway, Cousin Bette, Oscar and Lucinda, Julian Barnes’s Metroland and three works by Conrad. From a Daily Express review of The Talented Mr Ripley in February 2000, I learned three new words in the space of a single clause: ‘a conspiracy of patriarchal decorum in which even Dickie’s father colludes’. Also, from the same piece, ‘amorality’, ‘deferential’, ‘enervated’, ‘homoeroticism’.

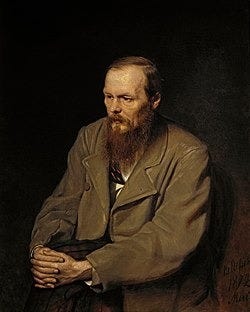

Knausgaard on DostoevskyI loved reading this New Yorker piece by Karl Ove Knausgaard about The Brothers Karamazov:

When I read the novel for the first time, I was twenty, the same age as Alyosha, and I toiled through the first hundred pages driven by sheer will—why on earth should I read lengthy explications of the Russian Orthodox Church and monasticism in the eighteen-sixties and its relationship to the state? But then something happened; something seemed to catch fire. I was suddenly inside something, and wanted nothing more than to remain there . . . I read the novel the way I had read books as a child, with no thought of myself, no thought for my circumstances: my entire self was contained within the book. Nor did I think about what I was reading; I didn’t analyze anything, didn’t mull anything over—everything except feelings and presence was blotted out by the white incandescent light that reading filled me with.

I read The Brothers Karamazov for the first time a couple of years ago. I got the odd flash of incandescent light. But a lot of it really is turgid (in my view) stuff about Russian orthodox monasticism.

I have to confess I’m not generally a Dostoevsky fan (with the exception of Crime and Punishment which is just incandescent light all the way). I’m clearly wrong in my antipathy as the consensus of intelligent people is firmly against me. But I do cherish the characteristically robust remarks the critic John Carey makes about Dostoevsky in his memoir The Unexpected Professor:

I found his plots rambling and his sentimental religiosity – well, just sentimental religiosity, especially in The Idiot. I know this may seem shallow and philistine, but I think it’s a reaction Dostoyevsky tempts you to have, to see if you’ve got the depth he requires of you, and I hadn’t.

Dostoevsky - disliked by me and John Carey

From Cultural Capital via this RSS feed