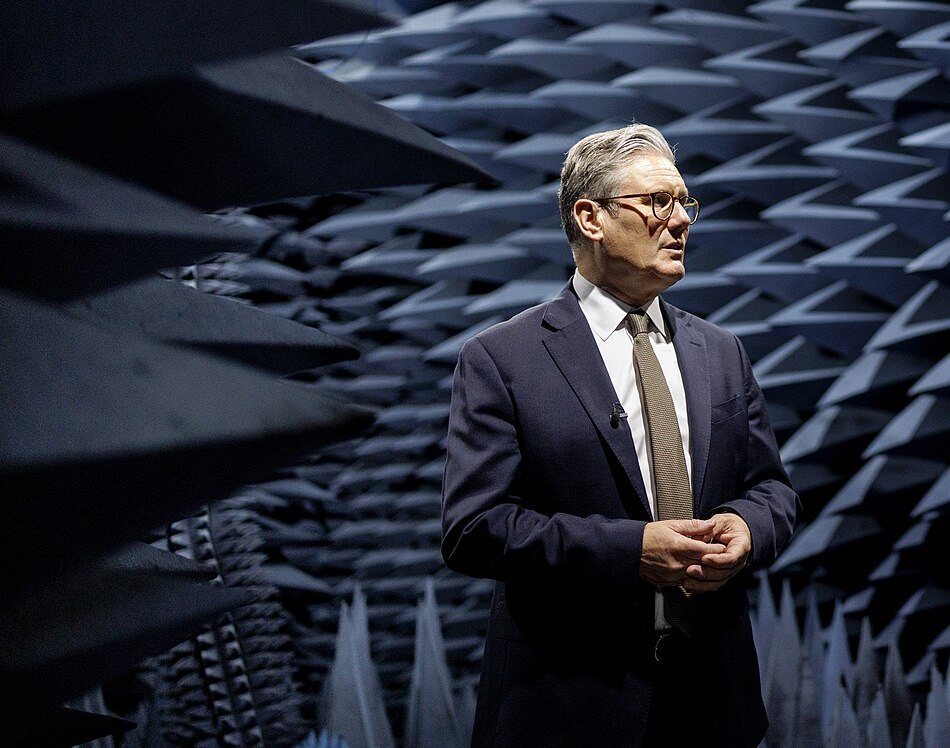

Photograph Source: Simon Dawson/10 Downing Street – OGL

‘When do you think Starmer goes?’ asked a friend last week, irate about the high arrest rate among non-UK nationals. In a Focaldata poll, at the same time, Reform UK leader Nigel Farage had just overtaken Keir Starmer on who would make a better prime minister. I may have wanted to challenge my friend’s despair, but both wondered whether Starmer was holding back on something—some final card. Also, there were whispers of Labour MPs plotting to oust him after the forthcoming Budget.

The UK is restless and anxious. The prime minister is uninspiring. According to YouGov, only one in four Brits now view Starmer favourably. It is a powerful sea change. Look beyond the energised Green Party—which has edged ahead of Labour in one polling series—and note the unhappy space in which the Conservatives and Reform UK now battle. It’s all about immigration first, the economy and housing second.

That said, only 24% think Reform UK would actually do a good job in running the country—also according to YouGov. “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle,” wrote George Orwell. Meanwhile, a recent Electoral Calculus model (MRP, June 2025) estimates the Conservatives at 19% of the national vote.

People are still perplexed by how the UK went from a natural liberal mindset to one of xenophobia, paranoia, and lovelessness. The grey drizzle competes daily with a depressed soul. But then, people peer across the Atlantic. The UK doesn’t witness its leader indulging in fantasies of authoritarian spectacle—no AI-assisted sky-drops by imaginary gruppenführers, or sycophantic corporations financing the destruction of an otherwise security-heavy Downing Street under cover of darkness. Fair-mindedness remains, for some at least, a preferred civic disposition. There are problems, sure there are—way too many—but there are still elements of this culture sturdier than its detractors think.

Consider the basics. There is free healthcare, even as Reform proposes a parallel insurance-based model. Despite American oligarchs trawling social media to prove otherwise, zeroing in on the recent train stabbing, UK cities are walkable by global standards—there are aberrations everywhere in the world—and knife crime actually fell in the UK in the past year… Weather is mild—not yet tornado or wildfire country. Granted, there is drama, but very few guns.

We know the economy is taking a battering, too, but it still has a good services sector, especially in professional and financial services. Not everyone is fleeing these shores, despite stories to the contrary. It may be small fry but the UK economy grew by 0.7% in the first quarter of 2025—the fastest pace in a year—actually helped by growth in the services sector.

Of course, none of this is a guarantee of prolonged or broad-based popularity.

I suspect people wanted to like him. Those who know him swear he’s great company. Yet when he addresses the nation today, voters feel disengaged. It’s dispiriting. Competence is valuable—but in an era driven by spectacle, it doesn’t energise or inspire the public. In a TikTok world, wanting simply to govern rather than perform can seem almost alien. Perhaps ordinariness is a virtue—but it seldom breeds popularity.

Another YouGov poll noted that Starmer’s favourability rose from 26% in mid-February to 31% in early March, and the proportion with an unfavourable view dropped from 66% to 59%. But this uptick was connected to his hosting of a peace-conference in London and his Ukraine-related engagement.

The country itself is sliding. Would a more personal story about Starmer—who he is, what he stands for—help? Is he too much the former lawyer—his tidiness, the neat tie, the breath held before he answers? Does caution make him appear too distant? Many within the Labour Party, especially Muslim MPs and councillors, believe his response to Gaza was too circumspect, or ambiguous, even as others accused him of being too pro-Israel or too cautious.

Away from all this, is he holding something in reserve—that rumoured card up the sleeve?

And what is Starmerism anyway? To many, it feels like process over purpose. Few sharp interventions, few defining statements. Voters are tired of promises. They want results, even if structural change takes time.

Reform UK has capitalised on this. Belief, even raw belief, often resonates more than itsy-bitsy spreadsheets.

Yet beneath it all, for those attuned to broader patterns, there does hum a modern disappointment that began in earnest with Brexit. People still apologise for mentioning the “B word,” as though acknowledging the obvious were a social offence. Covid and Ukraine hit the country hard, but Brexit was self-inflicted.

My friend at the top of this piece for example will not concede that Brexit was a mistake. “Just look at the state of Europe,” he insists. But if Europe is struggling, I ask him, didn’t Brexit help contribute towards this?

Which brings us back to that speculative “card.” My friend is paid to predict things. Though no fan, he admits that Starmer’s long-term play, if he continues as prime minister, could be reintegration with Europe. If this is the intention, then perhaps Starmer will get to reveal something significant after all, not just about the UK’s global role, but about its character—and what kind of nation it wishes to be again.

“It’s the last big card he has to play,” says my friend. “My guess is he makes a referendum part of his next manifesto. But he can’t play it too early—or too late.”

The post Starmerama: When Governance is Not Enough appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed