Allegory of Nobility and Virtue by Tiepolo

Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital!

This week in The Times I wrote in defence of the Enlightenment. As the highly technologically sophisticated society of the twenty-first century slides ever further into bigotry and unreason the achievements of the scientists and philosophers of the eighteenth century seem ever more amazing. I think the careers of some of the great heroes of the Enlightenment have lessons for us as we fight back against our new dark ages.

Thanks for reading Cultural Capital! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

How co-evolution shapes societiesHere is another great piece from Brian Klaas on co-evolution. I only discovered his writing recently. I’m very glad I stumbled across him.

This essay is full of interesting examples of co-evolution in nature. Co-evolution describes the process by which two mututally-dependent species evolve in tandem, shaping each other’s destiny.

For instance, why do avocados have such large stones? Co-evolution with mega sloths:

Some species that live today co-evolved with another species that no longer exists; the survivors that persist are called evolutionary anachronisms, or evolutionary ghosts, because they evolved in tandem with something that later disappeared.11

To find an evolutionary ghost, you need only look to the avocado. The avocado seed is ridiculously large—and there’s nothing alive today in their natural environment that could easily spread them. They evolved in an era of much larger megafauna, such as giant ground sloths, who would easily disperse the avocado seeds. Back then, the pit size was perfect; now it’s a hindrance to survival. (However, avocados continue to survive and thrive because humans now do the seed dispersal instead of the sloths.)

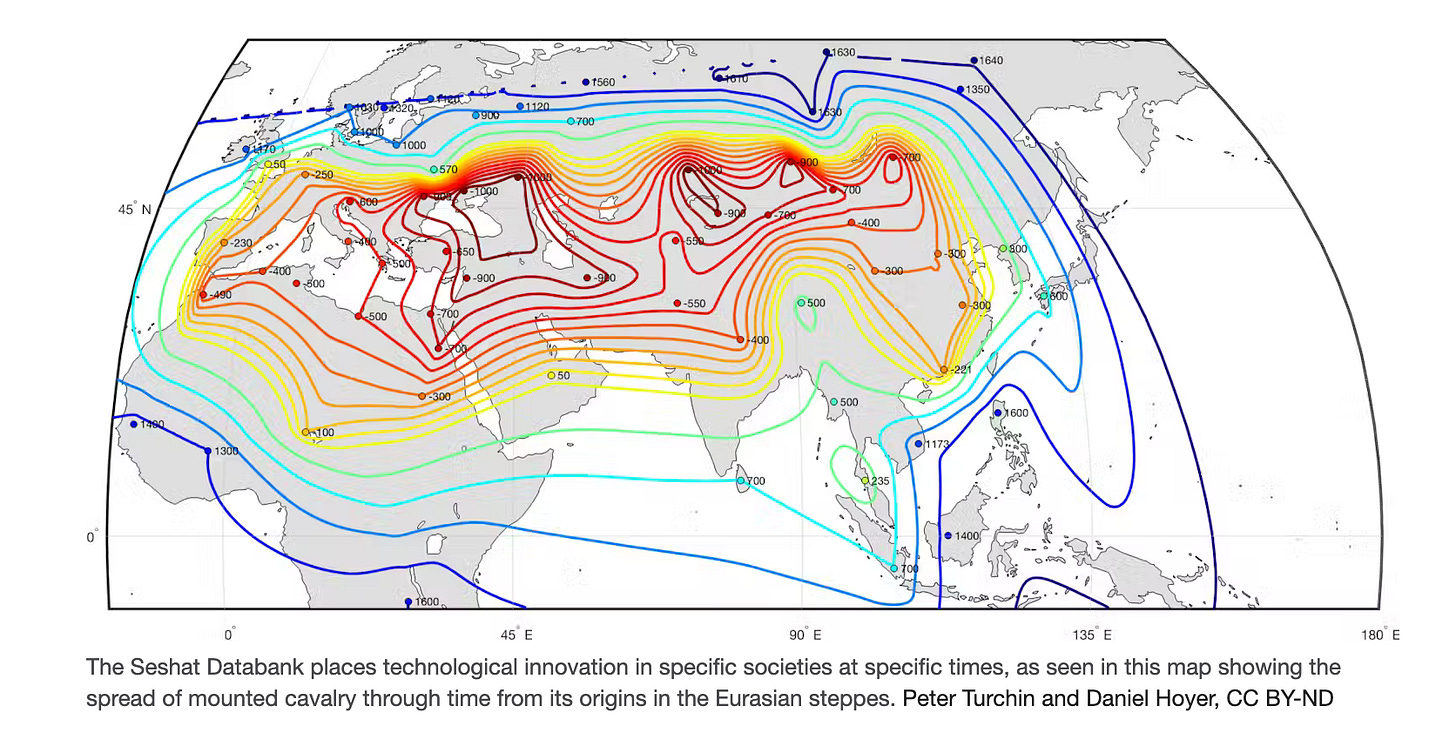

Human history is shaped by co-evolution too. For instance human-horse co-evolution enabled the development of cavalry and the spread of the first great Eurasian empires:

two mutations enabled humans to ride horses. The first one (ZFPM1) made horses less mean, while the second one (GSDMC) enabled them to better bear weight. Both gene variants were very rare at the beginning of the third millennium BCE, but became common by the end of the millennium. Clearly, there was very strong (artificial) selection that drove this genetic shift. . . It would not be much exaggeration to say that it was thanks to ZFPM1 that mega-empires and mega-religions appeared during the Axial Age.

And, of course, as Klaas interestingly explains in his essay, societies co-evolve not just with animals but with each other.

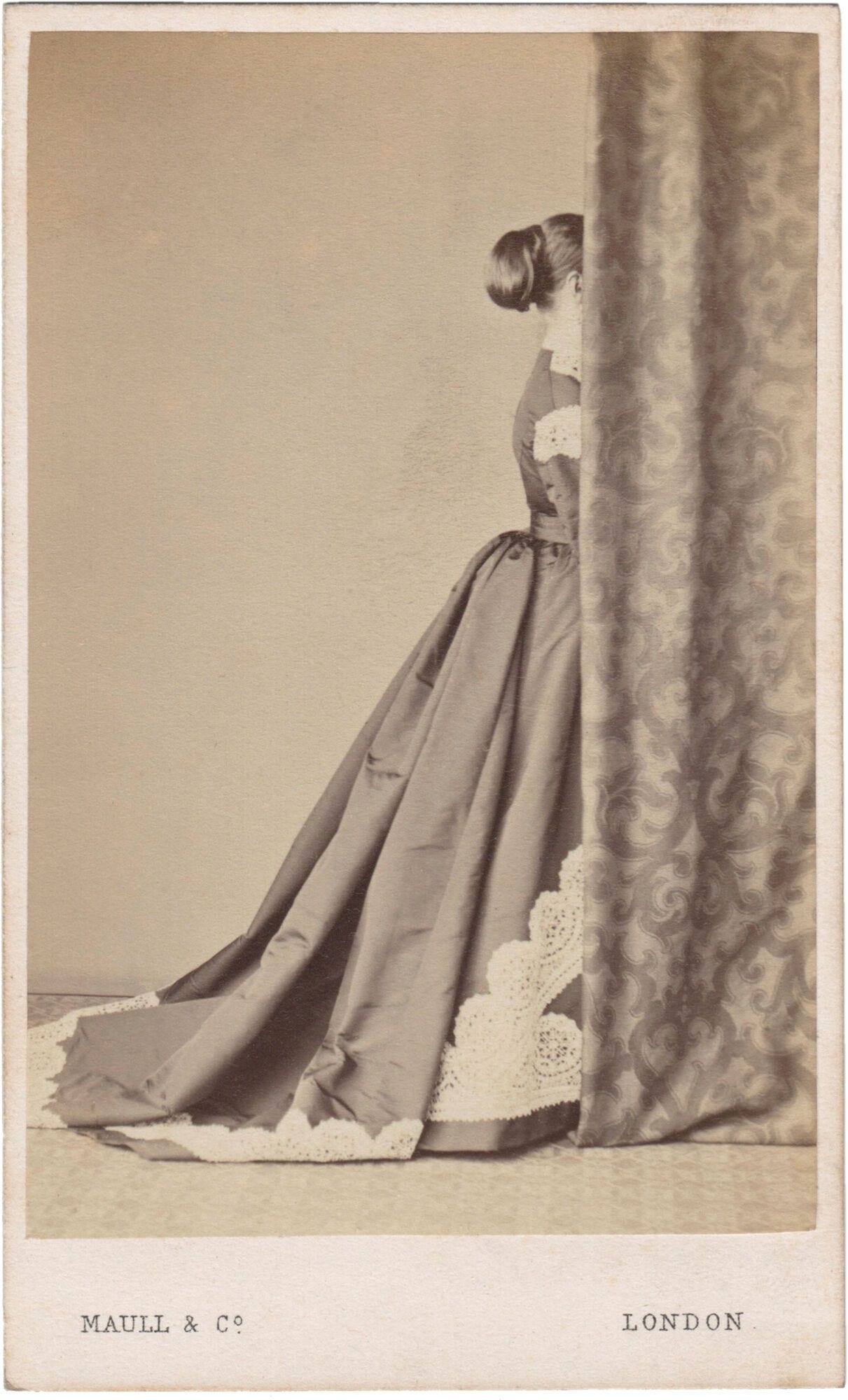

Cartes de visitesI missed it when it came out earlier this year but this is a wonderful piece by Tom Crewe on the Victorian craze for "carte de visite” portrait photographs.

The Victorians went mad for them and the world filled up with photographs — in homes, in shop windows, in the press. As Crewe says, “the carte de visite made the world visible to itself”.

The “effect was as radical as film or television or the internet”.

Anybody and anything could be photographed, and the photograph could travel anywhere.” For instance,

Max Beerbohm remembered going as a child to inspect the London Stereoscopic Company’s ‘great long double window on the eastern side of Regent Street’ and realising for the first time that his political heroes, read about in the papers and cartooned in Punch, existed as real people, ‘tailored and hosier’d as men’. What was on offer was a new kind of physical and imaginative intimacy with distant lives.

The idea you could buy and own a photograph of a distinguished person (even a monarch) shook people’s sense of how the world is supposed to work:

It was so unexpected of Queen Victoria to decide in late 1862 to make available for purchase images of herself and her children grieving for Prince Albert (gazing at his bust, wreathing it in flowers etc) that at least one writer in the Photographic News was convinced they were fake

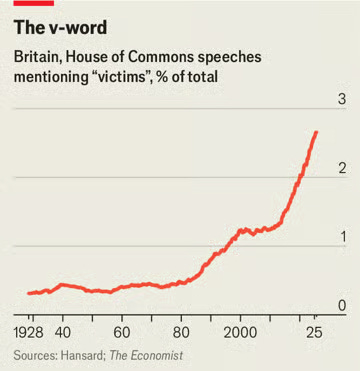

How victims took over politicsThis is an interesting piece from The Economist on how victims took over British politics: “Since the start of 2020 “victims” have been mentioned in Parliament 16,515 times, more than “Brexit” (10,797 times), “welfare” (9,978), “immigration” (8,644), “pensioners” (3,438) and “voters” (2,540).”

Victims, The Economist argues are “apex stakeholders” in politics.

Normal rules for decisions—risk, cost, proportionality—are thrown away when they are involved. What if a headline suggests ministers snubbed victims? Write the cheque. Civil servants, always cautious, become cowards. Campaigners know this. The unedifying spectacle of a grieving parent wheeled in front of cameras to push a particular policy, whether limits on smartphones or ninja swords, has become a political trump card.

The problem, of course, is that what is best for one newsworthy victim isn’t necessarily what’s best for society as a whole. This hyper-personalisation of social issues distorts policy. It makes it hard for politicians to take into account trade-offs and wider structural challenges. For instance “Martyn’s law, named after a victim of a suicide-bombing at a concert in Manchester in 2017, requires any venue that can hold more than 200 people to have an anti-terror plan, even if it is a village hall.”

Frederick the GreatI’m currently reading Tim Blanning’s biography of Frederick the Great. As I’ve often said, Tim Blanning is one of our greatest living historians and the book is brilliant.

Frederick the Great not only conquered tracts of northern Europe, he had a remarkable cultural hinterland. He corresponded with Voltaire, designed buildings and composed 121 flute sonatas. He also wrote erotic and satirical verse and an opera about the Aztec emperor Montezuma.

This was his routine:

The Austrian ambassador reported that immediately on rising at – or before – the crack of dawn, Frederick paced up and down playing his flute while waiting for his coffee to appear. Once the morning military and political business had been completed, he returned to his inner sanctum and his instrument until it was time for the main meal of the day. He told d’Alembert that he never knew what he was playing, but that his improvisations helped him to think.

Every evening, starting between six and seven o’clock, there was a private concert lasting around two hours and usually attended only by the seven to ten musicians involved, although occasionally guests were admitted. At these, Frederick performed three to five concertos and a number of sonatas, composed either by himself or by [the court virtuoso] Quantz.

Well, I suppose Keir Starmer also plays the flute…

How the fall of Rome prefigures modern declineHere is the cultural historian Peter Gay writing about the moral and intellectual decay of the Roman Empire. The parallels with our own time are remarkable:

As the second century went on, the rage abated, but regret swallowed creativity, and pessimism became the pervasive undertone in philosophy and poetry alike.

There was nothing new about this lassitude, this gradual but irreversible return from thought to myth, from independence to nostalgia: symptoms of this “failure of nerve” (as Gilbert Murray has called it) were visible as early as the last years of the Republic.

By the second century the symptoms were marked, and everywhere: the Roman Empire was swarming with superstitions and elaborate mystery religions; the masses and even educated men were overwhelmed by a disturbing feeling of sinfulness and of dependence on inscrutable powers, a growing desire for immortality and an obsessive fear of demons, a curiosity about religion that moved from intellectual inquiry to the pathetic hope for salvation.

It seemed as though the traditional choice offered by the great philosophers—the life of reason, responsibility, autonomy, and freedom from dependence on myth—was too strenuous, or too frightening, for the world of the Roman Empire, a world marked by severe social dislocation, the disappearance of local loyalties, the devastating contrasts of shameless luxury with abject poverty, and perhaps worst of all, the insurmountable separation of a narrow elite from the masses, crude in their beliefs, brutal in their conduct of life, childlike in their dependence on irrational powers.

The philosophers did not deign to educate the believers, and in time the believers overwhelmed the philosophers.

Some philosophers proudly resisted the barbarization of their culture and the dilution of their rationalist heritage; but others converted their philosophy into authoritarian dogmas or ecstatic experiences, seeking in it certainty and salvation rather than intellectual clarity and the opportunity for continued questioning. This was, perhaps, the most threatening symptom of all: the blending of religion and philosophy.

This is just an aside in Gay’s brilliant history of the Enlightenment (which I’m also reading at the moment and highly recommend). I know that as an account of the decline of the Roman Empire this passage is a bit outdated but still it’s remarkable how relevant it sounds.

On that cheerful note…

Until next time!

James

From Cultural Capital via this RSS feed