To understand what just happened in this week’s elections—notably Zohran Mamdani’s win in New York City, Mikie Sherrill’s win in New Jersey, and Abigail Spanberger’s win in Virginia—wind back the clock five years.

In 2020, Joe Biden won by promising that he could restore normalcy to American life. That did not happen. As the biological emergency of the coronavirus pandemic wound down, the economic emergency (inflation) took off. An affordability crisis broke out around the world. The public revolted. Last year, practically every incumbent party in every developed country lost ground at the ballot box.

So it went in the United States. In 2024, Donald Trump won an “affordability election.” I’m calling it that because affordability is what Trump’s voters said they wanted more of. Gallup found that the economy was the only issue that a majority of voters considered “extremely important.” A CBS analysis of exit-poll data found that eight in 10 of those who said they were worse off financially compared with four years ago backed Trump. The AP’s 120,000-respondent VoteCast survey found that voters who cited inflation as their most important factor were almost twice as likely to back Trump.

So Trump won. And for the second straight election, the president has violated his mandate to restore normalcy. Elected to be an affordability president, Trump has governed as an authoritarian dilettante. He has raised tariffs without the consultation of Congress, openly threatened comedians who made jokes about him, pardoned billionaires who gave him and his family money, arrested people without due process, overseen the unconstitutional obliteration of the federal-government workforce, and, with the bulldozing of the White House East Wing, provided an admirably vivid metaphor for his general approach to governance, norms, and decorum.

[Read: ‘None of this is good for Republicans’]

A recent NBC poll asked voters whether they thought Trump had lived up to their expectations for getting inflation under control and improving the cost of living. Only 30 percent said yes. It was his lowest number for any issue polled. The affordability issue, which seemed to be a rocket exploding upwards 12 months ago, now looks more like a bomb to which the Republican Party finds itself tightly strapped.

So again, we have an affordability election on our hands.

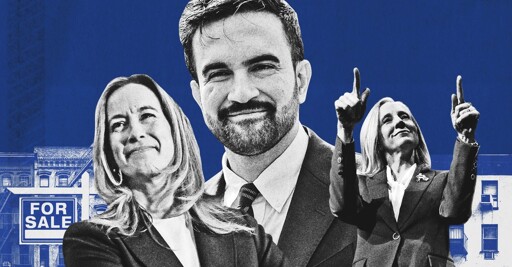

On the surface, Mamdani, Spanberger, and Sherrill emerged victorious in three very different campaigns. Mamdani defeated an older Democrat in an ocean-blue metropolis. In Virginia, Spanberger crushed a bizarre Republican candidate in a state that was ground zero for DOGE cuts. In New Jersey, Sherrill—whose victory margin was the surprise of the evening—romped in a state that had been sliding toward the Republican column.

Despite these cosmetic differences, what unified the three victories was the Democratic candidates’ ability to turn the affordability curse against the sitting president, transforming Republicans’ 2024 advantage into a 2025 albatross. Here’s Shane Goldmacher at The New York Times:

Democratic victories in New Jersey and Virginia were built on promises to address the sky-high cost of living in those states while blaming Mr. Trump and his allies for all that ails those places. In New York City, the sudden rise of Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, the democratic socialist with an ambitious agenda to lower the cost of living, put a punctuation mark on affordability as a political force in 2025.

Each candidate arguably got more out of affordability than any other approach. Mamdani’s focus on the cost of living in New York—which included some genuinely brilliant ads on, for example, “Halalflation” and street-vendor permits—has been widely covered. Less ballyhooed, but just as important, is that Spanberger and Sherrill also found that the affordability message had the biggest bang-for-buck in their own advertisements. An analysis shared with me by the polling and data firm Blue Rose Research found that “the best-testing ads in both Virginia and New Jersey focused on affordability, tying rising costs to Trump and Congressional Republicans.”

Tuesday night showed what affordability can be for the Democratic Party—not a policy, but a prompt, an opportunity for Democrats to fit different messages under the same tentpole while contributing to a shared national party identity: The president’s a crook, and we care about the cost of living. In New York City, Mamdani won renters by 24 percentage points with a specific promise: freeze the rent. In New Jersey, Sherrill won with a day-one pledge to declare a state of emergency on utility costs, which would allow her to halt rates and delete red tape that holds back energy generation. (The opening line of her mission statement: “Life in New Jersey is too expensive and every single New Jerseyan who pays the bills knows it.”) In Virginia, Spanberger went another way, relentlessly blaming rising costs on Trump.

What’s notable is not just what the above messages have in common but what they don’t. Sherrill focused on utility costs, whereas Mamdani focused on rent. Mamdani ran a socialist campaign to energize a young left-wing electorate, whereas Spanberger’s task was to win a purple state with an outgoing Republican governor. Each candidate answered the affordability prompt with a message tailored to the electorate: Affordability is a big tent.

The affordability message was especially successful at bringing young voters back to the Democratic fold. After the 2024 election, it looked like young people were listing to the right. Tuesday night was not the ideal test of that theory, because off-year elections tend to have a smaller and more educated (and therefore more naturally anti-Trump) electorate. But the pollster John Della Volpe reported that young voters “anchored the Democratic turnaround” in Virginia, where 18-to-29-year-olds delivered a 35-point margin for Spanberger, the largest for Democrats since 2017.

It’s easy to understand why young voters would appreciate an emphasis on the cost of living. Just this week, the National Association of Realtors announced that the median age of first-time U.S. homebuyers has jumped to a new record of 40. “Zohran’s campaign centered cost-of-living issues, and he at least appeared consistently willing to look for answers wherever they may present themselves,” Daniel Racz, a 23-year-old sport-data analyst who lives in New York, told me. “I think of his mentions of the history of sewer socialism, proposed trial runs of public grocery stores on an experimental basis, and his past free bus-pilot program, which showcased a political curiosity grounded in gathering information to improve his constituents’ lives.”

Amanda Litman, a co-founder and the president of Run for Something, oversees a national recruitment effort to help progressives run for downballot office. On Tuesday, the organization had 222 candidates in general elections across the country. “Nearly every candidate who won an election for municipal or state legislative office was talking about affordability, especially as it relates to housing,” she told me. “Housing is the No. 1 issue we’ve seen people bring up as a reason to run for office this year.”

The affordability approach has several strengths. Because it is a prompt rather than a policy, it allows Democrats to be organized in their thematic positioning but heterodox in their policies. A socialist can run on affordability in a blue city and win with socialist policies; a moderate can run on affordability in a purple state and win with the sort of supply-side reforms for housing and energy that animate the abundance movement. At a time when Democrats are screaming at one another online and off about populism versus moderation, the affordability tent allows them to be diverse yet united: They can run on tying Trump to the affordability crisis while creating messages fit for their respective electorates.

[Read: An antidote to shamelessness]

This next bit is a bit speculative, but another advantage of centering affordability may be that it is easier for members of a political coalition to negotiate on material politics than on post-material politics. Put differently, economic disagreements within a group are more likely to produce debate and even compromise, whereas cultural disagreements are more likely to produce purity tests and excommunication. If a YIMBY left-centrist and a democratic socialist disagree about the correct balance of price controls and supply-side reforms to reduce housing inflation in New York City, that might lead to a perfectly pleasant conversation. But perfectly pleasant conversations between political commentators about, say, ICE deportations or trans women in college sports don’t seem common. If this is true, it would suggest that the spotlight of Democratic attention shifting toward affordability might ameliorate the culture of progressive purity tests in a way that would make for a bigger tent.

Affordability politics also poses a distinct challenge. At the national level, Democrats do not have their hands on the price levers, and they won’t for at least four more calendar years. Even if they did, the best ways to reduce prices at the national level include higher interest rates (painful), meaningful spending cuts (excruciating), or a national tax increase (dial 911). Even at the local level, affordability politics in an age of elevated inflation, rapidly growing AI, and complex impediments to affordable housing can easily promise too much—or, to be more exact, offer a set of dangerously falsifiable promises.

Affordability politics thrives because of the specificity and clarity of its pledge: Prices are too high; I’ll fix it if you give me power. But politics isn’t just about the words you put on your bumper stickers; it’s about what you do if the bumper stickers work. Building houses takes time, even after reducing barriers to development and improving access to financing. Actually lowering prices can take even longer. Energy inflation is a bear of a problem, with transmission prices rising and data-center construction exploding. After Americans learn whose affordability messages win at the ballot box, they’ll learn whose affordability policies actually work and (perhaps) keep them in office.

Affordability is good politics, and a Democratic Party that focuses on affordability at the national level, and supports motley approaches to solving the cost-of-living crisis at the local level, is in a strong position going into 2026. But saying the word affordability over and over doesn’t necessarily guarantee good policy outcomes. In fact, it doesn’t guarantee anything. Which is why at some point on the road back to relevance, the Democratic Party needs to become obsessed with not only winning back power but also governing effectively in the places where they have it.

This article was adapted from a post on Derek Thompson’s Substack.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed