Jeffrey Epstein with unidentified soldiers in Africa. Photo from Epstein’s “birthday book.”

Jeffrey Epstein and Ehud Barak were specialists in war profiteering. At the end of his tenure as Israel’s defense minister and after his supposed “retirement,” Barak embraced a role as a salesman of Israeli security services to embattled governments, opening the door for Israeli intelligence leaders to shape the security apparatuses of several African nations, including the country of Côte d’Ivoire.

Quietly facilitating these efforts was Jeffrey Epstein, who died in jail in 2019. Epstein wrote at one point to Barak: “with civil unrest exploding […] and the desperation of those in power, isn’t this perfect for you.” Barak replied:, “You’re right [in] a way. But not simple to transform it into a cash flow.” Transforming unrest into cash flow, in the case of Côte d’Ivoire, involved brokering deals between the Israeli state and the embattled West African nation.

New details about Epstein’s role in Israeli intelligence operations in Africa have emerged from two sets of documents: an archive of leaked emails released by the Handala hacking group and hosted by non-profit whistleblower site Distributed Denial of Secrets and documents released by the U.S. House Oversight Committee last month. The latter set includes Epstein’s personal emails and appointment calendars, which provide clear evidence of Epstein’s involvement in Israel’s West African security negotiations in 2012, while Barak was still Israel’s Defense Minister.

The two men worked together as a conduit for Israel’s intelligence sector in Côte d’Ivoire, where Barak was welcomed as a representative of the Israeli government even after leaving public office. Epstein helped Barak deliver a proposal for mass surveillance of Ivorian phone and internet communications, crafted by former Israeli intelligence officials.

As in Mongolia, Epstein and Barak’s private deal-making evolved seamlessly into an official security agreement between Israel and Côte d’Ivoire in 2014. Since the agreement was signed, over a decade ago, President Alassane Ouattara has tightened his grip on power, banning public demonstrations and arresting peaceful protestors. In this October’s election, the octogenarian won a fourth term, in defiance of constitutional term limits, while opposition candidates were barred from participation.

Today, Ouattara continues to enjoy the support of Israeli security firms to help him maintain power. His Israeli-backed police state has squashed civic organizations and silenced critics. In the wake of the recent election, exiled activist Boga Sako Gervais denounced Ouattara’s authoritarian slide: “Under Ouattara, since 2011, freedoms of opinion, thought, and expression have been criminalized,” he said. “It has become forbidden to criticize the head of state.”

The story of Israel’s security agreement with Côte d’Ivoire is only one chapter in the saga of Epstein and Barak’s covert activities in Africa—it is reported here as the next entry in an ongoing series on Epstein’s ties to Israel’s intelligence.

Drop Site needs your help. An investigation we published last December is now the subject of a lawsuit filed by a top editor at the BBC. We stand firmly behind our journalism and will defend it vigorously. But we can only win—and we are confident we will—if we have the resources to fight. We’ve already spent roughly $40,000 defending our reporting, with significant ongoing legal and liability insurance costs ahead. Prolonged legal proceedings burden independent reporters and chill important work. But if our community of readers steps in to backstop us, that sends a message to litigants that they can file suit, but we can fight back.

Epstein, Israel, Ivory Coast: How Israeli Intelligence Built a Police State In West Africa

In late 2010, a disputed presidential election in the west African nation of Côte d’Ivoire triggered political upheaval and violence that rapidly destabilized the country. The UN certified Alassane Ouattara as the winner of a November 2010 runoff vote. But the outcome was not accepted by the rival incumbent, Laurent Gbago. After months of violence, a French and UN military intervention was launched in April 2011 to remove Gbago and drive him from the country.

After Gbagbo’s exile, Ouattara inherited a security apparatus fractured by the crisis, and his own hold on power was uncertain. The new president announced that his government had foiled a coup plot against him by officers still loyal to Gbagbo in June 2012.

Five days after that announcement, the new Ivorian president, who had a long career as an economist at the International Monetary Fund and a reputation as a technocrat, traveled to Jerusalem to meet Defense Minister Ehud Barak and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and discuss cooperation on science, technology, and counterterrorism. The following month, an Israeli delegation visited Côte d’Ivoire to field Ouattara’s questions about Israel’s security apparatus and rebuilding the Ivorian presidential army.

While Israeli and Ivorian officials sat in hotel conference rooms and took press photographs, American financier Jeffrey Epstein was across the globe, engaged in shadow diplomacy to develop further ties between Israel and the new Ivorian leader.

On June 18, 2012, the very same day Barak was meeting with Alassane Ouattara in Jerusalem, according to Epstein schedules released by the U.S. House Oversight Committee, his son David Dramane Ouattara was in New York City for an appointment with Epstein.

On September 12, three months later, Epstein met with Ouattara’s niece Nina Keita, whom he had known since at least 2002; as a young fashion model in Jean Luc Brunel’s Karin Models agency, she had traveled on his “Lolita Express” plane between New York and Paris. After Keita’s visit, records show that Epstein went straight to the Regency Hotel in New York for a private meeting with the Israeli defense minister.The next month, Epstein flew to Africa. In a note to his assistant, he instructed her to arrange to switch planes in London before flying to Côte d’Ivoire, Angola, and Senegal. There are no flight logs documenting the Africa trip.

The flurry of visits appeared to pay dividends for Epstein, Barak, and the Israeli government. Two weeks after Epstein’s trip to Africa, the Ivorian Interior Minister Hamed Bakayoko was in Tel Aviv to meet with Barak and discuss a bilateral security accord focused on intelligence and cybercrime.

Epstein’s assistant sends schedule for DC meeting with Barak. Source: House Oversight documents.

Epstein discusses October travel with his assistant, including stop in Côte d’Ivoire. Source: House Oversight documents.

Barak has previously claimed his “private investments” with Epstein were conducted as a private citizen and unrelated to official Israeli state affairs. The documents released by the House in October, however, suggest that Epstein played the same “fixer” role while Barak was still the sitting Defense Minister of Israel. Barak did not respond to a request for comment.

Less than a year later, Barak resigned from the Israeli government. In 2011, Barak had split from Israel’s Labor Party and formed a small “centrist” faction called Independence. Despite his long history in government, including a past stint as prime minister, his tiny party was predicted to get wiped out in the January 2013 Knesset election.

He left his position as defense minister on March 18, 2013, before an agreement with Côte d’Ivoire was reached. Barak’s departure from government did not end his role negotiating security agreements for Israel, however. After he left his formal government role, emails and private records show that he finished negotiating the intelligence deal with Côte d’Ivoire covertly. In these efforts, Epstein provided critical assistance.

On March 19, 2013, one day after leaving his government post, Barak received an email from his business partner and brother-in-law Doron Cohen, containing materials prepared by MF Group, a French-Israeli security contractor run by Michel Farjon. The consortium of companies, spread across several European countries, did security work in Africa; the group had been involved in a controversial sale of military helicopters to the government of Cameroon.

An email address associated with Farjon sent details of MF Group’s planned projects in Côte d’Ivoire: a mobile and internet communications surveillance center and a video monitoring center in Abidjan. According to email logs, Barak and Farjon met three days later, on the fourth floor of G Tower in Tel Aviv, on March 22, 2013.

Barak and Cohen made efforts to keep these communications secret. Farjon’s emails to Cohen never mentioned Barak by name—instead using cryptic subject lines like “files to be transferred to your friend”—and Barak and Cohen’s emails referred to Farjon by his initials “MF,” often in connection with another player called “AM,” or “Maoz.” Cohen took precautions to ensure their conversations were not overheard; on April 12, he emailed Barak: “I had a good meeting today with MF and AM. I’ll be glad [to] update you. I’ll be in the car alone at 0415 am until 5am.”

Reached for comment by Drop Site at the same email address that appears in the files, Farjon acknowledged that the documents containing proposals for Côte d’Ivoire had originated from his company. But, he said, his company did not actually engage in business in the country and denied that he had ties with Barak and Cohen. “The documents are accurate as previously stated. No cooperation with Barack, Cohen, Epstein. No deal with Ivory Coast, nor any cooperation,” Farjon said. Drop Site was unable to reach Cohen.

Although the talks were proceeding briskly, the momentum was halted after an unexpected report came from the United Nations.

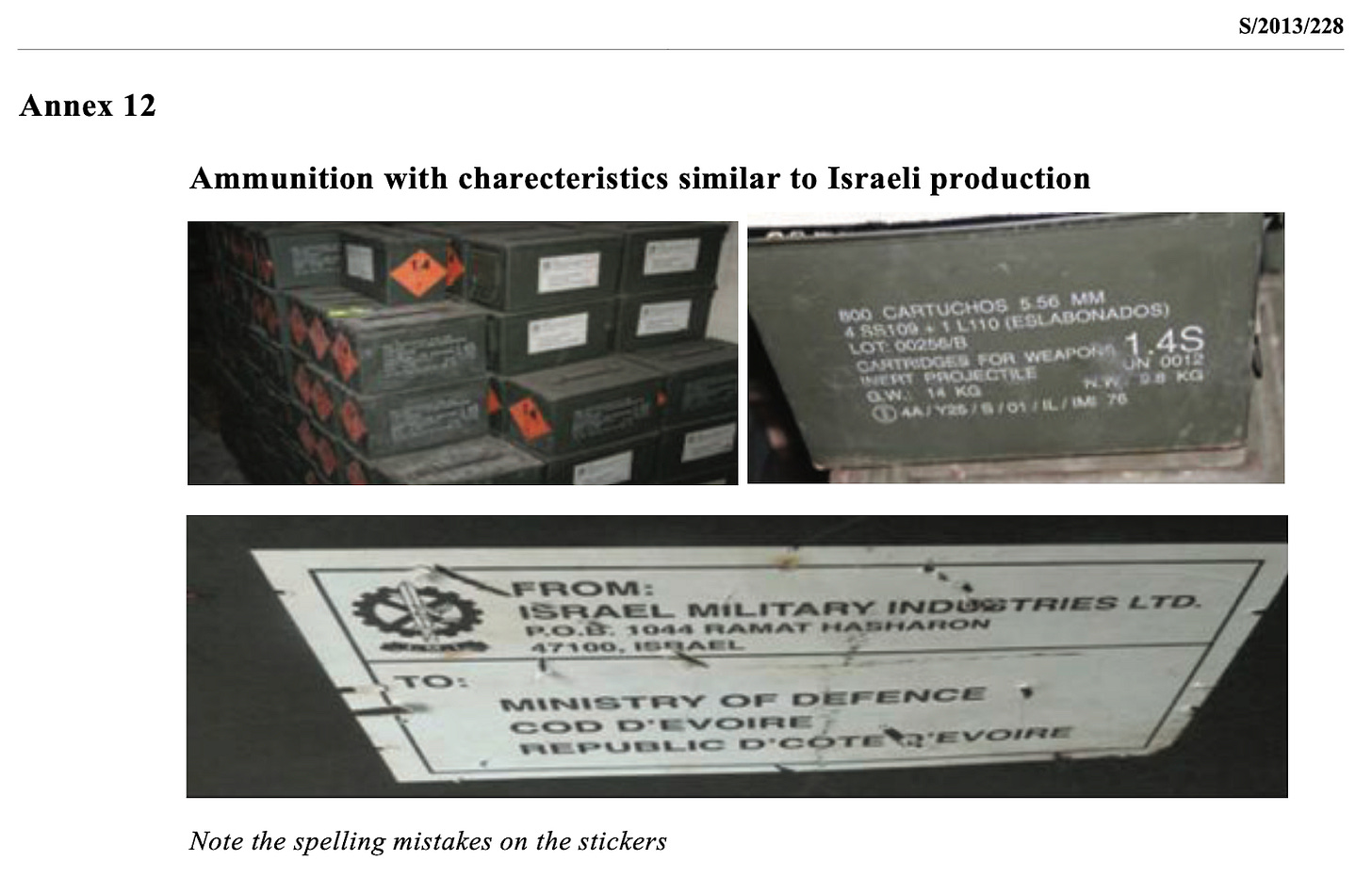

Since 2004, during the country’s first civil war, Côte d’Ivoire had been subject to a UN arms embargo that blocked weapons sales and applied strict requirements for even “non-lethal” training and equipment transfers. On April 17, 2013, the UN Security Council reported the discovery of “dozens of crates” of Israeli ammunition at the presidential palace and the Attécoubé naval base, likely transferred to Gbagbo’s security forces during the 2010-2011 crisis. The crates had Israel Military Industries labels and Spanish markings; the report suggested the ammunition had been relabelled and retransferred to Côte d’Ivoire from a third country.

UN Group of Experts Report, suspected Israeli ammunition crates with Spanish markings

On April 21, Cohen emailed Barak: “I met with MF and AM last night. We are facing a problem. We need to schedule a serious talk about them.” Cohen refrained from discussing the problem over email. Four days later, the Security Council announced it was extending the arms embargo on Côte d’Ivoire for another year.

Immediately upon his return to Israel, Barak made phone calls to Israeli security leaders with some connection to Côte d’Ivoire. On May 15, he called Amos Malka, the former head of Israeli intelligence and a recent chairman of Israeli armor manufacturer Plasan. Plasan had also been swept up in the sanctions enforcement: in addition to the Spanish-marked ammunition crates, UN embargo monitors had flagged a five-ton shipment of Plasan body armor to Abidjan.

Malka, like Barak, occupied a blurred public-private boundary in Israeli intelligence. Malka’s company Logic Industries was installing a surveillance apparatus in the United Arab Emirates under contract with a Swiss company, as Israel and the U.A.E. did not have direct security ties. The email logs do not disclose the subject matter of Barak and Malka’s phone call—but, after hanging up, Barak emailed Malka the résumé of a Spanish-Israeli logistics expert at the “Prime Minister’s Office,” a cover name for Shin Bet, Israel’s counterintelligence service.

“I have never worked with Mr. Barak since my retirement,” Malka told Drop Site when reached for comment, referencing his departure from the security services in 2002. “I know him very well but no business together.”

Barak called one more stakeholder on May 19, 2023: the Honorary Consul of Côte d’Ivoire in Israel, Michael “Micky” Federmann, chairman of the Israeli military technology giant, Elbit Systems. Federmann was experienced at navigating UN sanctions and West African politics; Elbit had supplied military helicopters to Côte d’Ivoire during the first Ivorian civil war.

Finally, on May 27, Barak called Sidi Tiémoko Touré, Chef de Cabinet (head of office) of President Ouattara. Barak emailed Touré after the call to formally request an audience with Ouattara, and they arranged a meeting in Abidjan in August.

In preparation for his West Africa trip, Barak asked private intelligence firm Ergo to prepare a briefing on Côte d’Ivoire. It contained a dossier on Ouattara and his inner circle and detailed organization charts of the state’s defense and internal security organs.

Meanwhile, Barak prepared paperwork for a “non-security” pretext to visit West Africa. On July 22, he received a document from his son-in-law Michael Menkin, a manager at the medical equipment supplier Elsmed, containing a brief proposal to build hospitals and diagnostic centers in Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire.

Barak arrived in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire on the first of August. According to an itinerary sent to him by Touré, Barak met with Marcel Amon-Tanoh, Ouattara’s chief of staff, and Hamed Bakayoko, Minister of the Interior and Security, on August 2, 2013, who shared more information about the Ivorian security apparatus. Barak and his wife even visited Amon-Tanoh’s home, and met his two daughters, both Oxford-educated graduate students in London. The next day, August 3, Barak met with President Ouattara and Paul Koffi Koffi, the deputy in charge of Defense.

Farjon, of MF Group, told Drop Site that he learned independently that Barak had indeed met with Ouattara, but said he did not know how his materials became involved. “I don’t see how or why Barak could have accessed my documents. Keep digging,” he told Drop Site.

Ehud Barak and wife Nili Priel at hotel Le bélier de Yamoussoukro, Côte d’Ivoire (August 2013). Photograph taken by Maud Amon-Tanoh, daughter of Marcel Amon-Tanoh, chief of staff of Alassane Ouattara.

“How Can We Move Forward”

Barak finally returned to Israel late at night in August. Upon arriving, emails show that Barak made a phone call to Stanley Fischer, the governor of the Bank of Israel and a close friend of Ouattara from their days at the International Monetary Fund during the late 1990s.

A few days later, Barak was contacted by Jean-Baptiste Gomis, the Ivorian ambassador to Israel, bearing gifts from Côte d’Ivoire. Gomis wrote: “i seize this opportunity to ask you for a meeting to talk about your impression of your visit in Cote d Ivoire and moreover how can we move forward.” Barak visited Gomis at his home soon after.

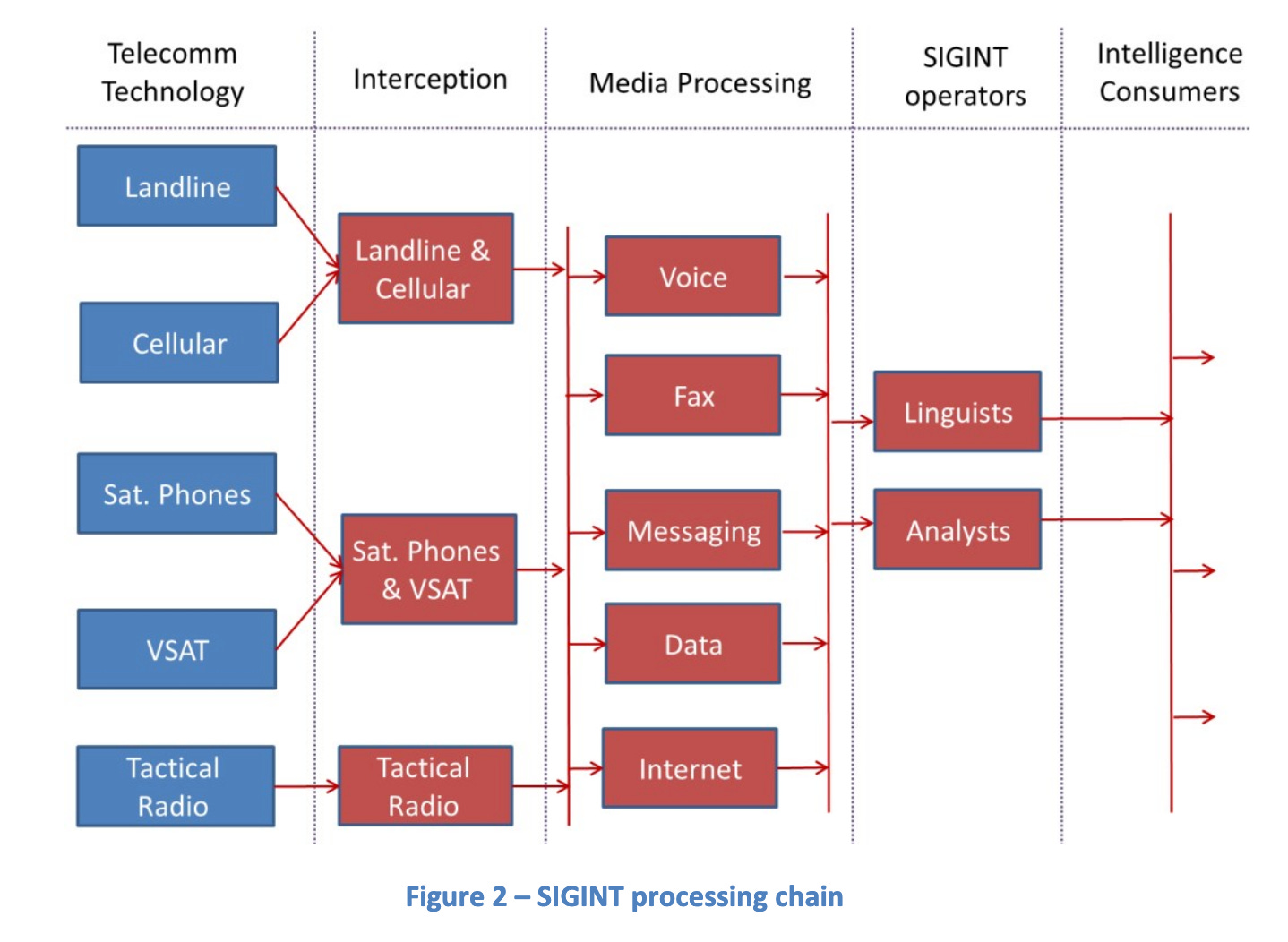

On September 16, 2013 the details of Israel’s offer arrived in Barak’s inbox. Barak received a proposal from Aharon Ze’evi-Farkash, former head of Israeli intelligence, for a SIGINT (“signals intelligence”) organization in Côte d’Ivoire.

The document, a 13-page PDF, mapped out the complete architecture for eavesdropping on phone calls, satellites, tactical radio, and “special targets” like cyber cafés. The data streams flowed to “media processing” servers, to be reviewed by analysts, then synthesized into reports for security leaders.

SIGINT processing chain included in proposal document.

The document was authored by Farkash and Amnon Unger, who developed these systems in occupied Palestine during the two periods of Intifada between 1990 and 2005. The two men had been senior commanders in Israel’s Unit 8200 signals intelligence unit, before branching off to other roles in the military and private sector.

Ic Preliminary Proposal1.37MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload

Farkash reminded Barak that he was operating in a gray area by sharing planning documents with a foreign country. He wrote to Barak in Hebrew: “The document is based on experience that has been accumulated during Amnon’s and my service in the unit… I believe this meets the ‘export‑of‑knowledge’ test. I thought it appropriate to bring this to your attention.” “Export-of-knowledge” (יצוא ידע) refers to Israel’s Defense Export Control Act, which requires a license for transfer of “defense know-how,” even unclassified, exploratory material like a technical spec.Barak replied to inform Farkash that he would “probably be in touch with the client toward the end of the month.” A few days later, Barak flew to New York where he visited Epstein, during the 68th Session of the United Nations General Assembly. Epstein had been coordinating meetings for Barak for that week.

Epstein had been helping manage Barak’s itinerary in anticipation of his visit, writing that “we should try to scheudle some people for dinners or lunches when you are here.” Epstein proposed several prominent business and political leaders: New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, British Ambassador Peter Mandelson, banker Ariane de Rothschild, and Joshua Cooper Ramo, advisor to former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

Epstein also planned a meeting for Barak with another, less famous guest—Sidi Tiémoko Touré, Chef de Cabinet for President Ouattara. Before arranging the meet, he made a phone call to Ouattara’s niece, Nina Keita, according to last month’s House Oversight release.

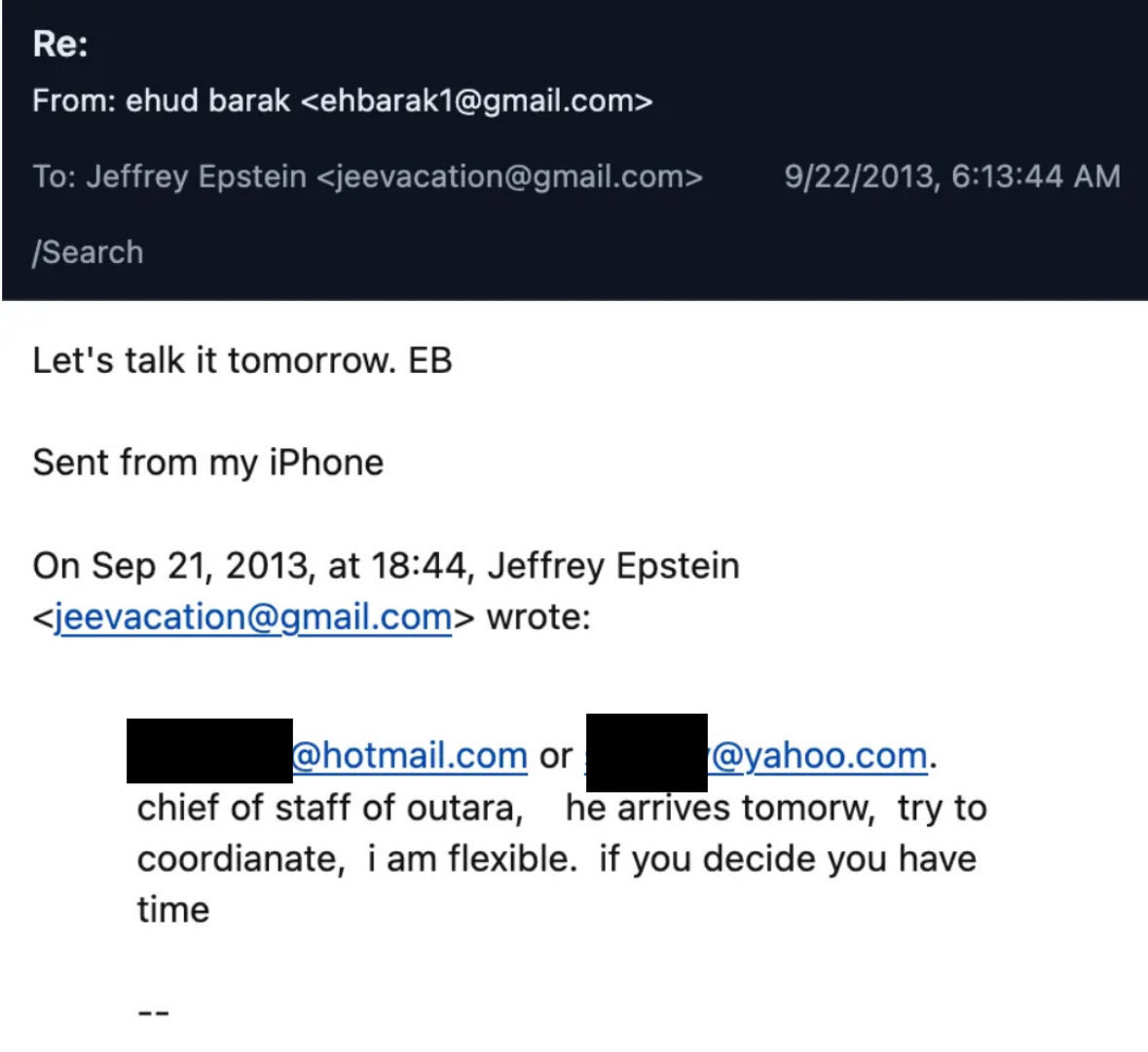

On September 21, Epstein sent Barak a message with Touré’s personal email address: “chief of staff of outara, he arrives tomorw, try to coordianate, i am flexible. if you decide you have time.” Barak planned to visit Epstein’s house the next morning for coffee: “Let’s talk it tomorrow.”

Emails between Epstein to Barak, September 21 and 22, 2013.

For several months, Barak’s email logs showed no further discussion of the Côte d’Ivoire plan. But Epstein’s calendars, released by Congress, show another meeting with Nina Keita on November 7, 2013—the same day UN peacekeepers launched a joint operation with Ivorian security forces to dismantle armed militias and remove illegal checkpoints. The security operation, followed by a UN Security Council meeting two weeks later, set the stage for the lifting of sanctions.

In March 2014, a piece was printed in the Israeli publication Calcalist about the pending Ivorian security deal, with glowing remarks about Barak’s business acumen and his reputation in the global defense industry. Barak gave a quote coyly denying his involvement, saying “These are private conversations, and the public has no interest in them.” Barak’s brother Avinoam emailed him a link to the story, and Barak replied, “Creative minds. HaLevay Alay,” a Hebrew saying for “I wish it were me.”

As winter turned to spring, the key players were mobilized again. Ouattara made preparations for a sweeping re-organization of the Ivorian intelligence apparatus. On April 10, 2014, he dissolved the intelligence service, Agence nationale de la stratégie et de l’intelligence (ANSI), and transferred its resources into a new body, the Coordination nationale du Renseignement (CNR).

Four days later, the UN Group of Experts issued a new recommendation to the UN Security Council to ease the arms embargo in Côte d’Ivoire and lift a decades-long ban on diamond exports. Non-lethal equipment used for maintaining “public order” no longer required notification to the UN Sanctions Committee. Barak’s wife Nili emailed Ivorian ambassador Gomis to arrange a meeting with Barak.

The UN embargoes were officially lifted on April 29, 2014. After Gomis returned to Israel from Abidjan in May, Barak’s wife invited the ambassador to G Tower for a meeting with Barak and Danny Yatom, the former head of Mossad. Gomis replied to the invitation: “I WAS IN COTE D IVOIRE LAST WEEK AND HAD A CHANCE TO TALK TO THE PRESIDENT HE IS WILLING TO TALK TO THE PRIME MINISTER EHUD BARAK NOT TO ANYONE ELSE.”

Barak emailed his wife: “Just tell Danny that following their request I will meet alone first and then arrange for a trilateral meeting.” Barak and Gomis met in the afternoon on May 29, 2014, and Gomis sent Barak’s wife a thank-you note afterward:

erev tovi would like to thank your husband for the nice meeting we had yesterdayi will report to the presidentthank you again for your patience

Two weeks later, on June 13, 2014, Avigdor Liberman, Israel’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, arrived in Côte d’Ivoire to sign an agreement on defense and internal security, accompanied by more than 50 businessmen, who came to evaluate prospective investments in the country. The dollar amounts of the deals conducted were not made public.

The efforts that Barak had taken with the assistance of contacts like Epstein bore fruit with this formal agreement signed between Israel and Côte d’Ivoire. But the deal was only one of several that the two men were orchestrating on behalf of Israeli interests on the continent.

On August 17, 2014, Doron Cohen emailed Barak with an update on their other endeavors in Africa: “I met the man who has some money in the bank in Africa. Very interesting and very generous offer. Let’s talk.” This time, even Barak was confused by the cryptic message. He replied: “Who is the man who has money in Africa and what does he offer[?] Catch me on the mobile to explain.”

Read more of Drop Site’s reporting on Jeffrey Epstein and Ehud Barak:

Jeffrey Epstein Helped Broker Israeli Security Agreement With Mongolia

From Drop Site News via this RSS feed