This is a lightly edited transcript of a talk I gave on Thursday at the Historical Materialism conference in London, as part of a panel on “Contesting Freedom, Equality and Value” that also included presentations by Tom Ladendorf, Luca Basso, and Emma Kauffmann.

The first section of Capital Vol. 1 is “Commodities and Money.” The second is “The Transformation of Money into Capital.” As the title makes clear, that one is transitional between the broad overview of commodities and money in general and the rest of the book. The remaining six sections cover the specific features of the capitalist mode of production—it’s structure, its laws of motion, and in the final section, its historical trajectory from its origins in violent dispossession of peasants to its future demise via the expropriation of the expropriators.

OK, so what’s the relationship between those first two sections—again, “Commodities and Money” and “The Transformation of Money into Capital”?

I agree with the longstanding view held by, most famously, Engels, but also by Rosa Luxemburg and a lot of other people, that Part One isn’t about anything specific to capitalism yet. I think we should take Marx seriously in Ch. 1 n. 15, where he says that “at this stage” of the book, we’re making the simplifying hypothetical assumption that wage labor doesn’t “exist at all.”

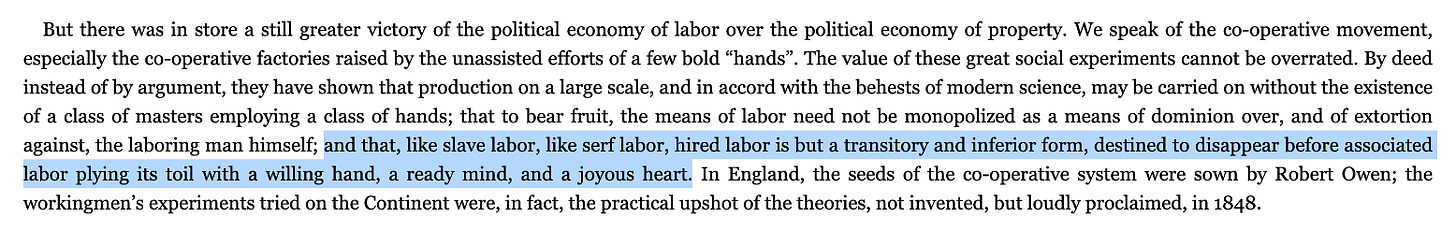

And we should recall Marx’s history of using “wage labor” or “hired labor” as a synonym or near-synonym for the capitalist mode of production, for example, here in an address he gave just a few years before the publication of Capital:

The context in that one, by the way, was his celebration of the importance of worker cooperatives, which he called “great social experiments” whose value can’t be overestimated because they point to the possibility of a post-capitalist future. Let’s put a pin in the subject of cooperatives, though, while we go back to Capital.

Again, assuming that by “capitalism” we mean a society where the predominant mode of production is profit accumulation through the employment of wage labor, that doesn’t exist yet in Pt. 1. What Marx is doing instead, there, is building up a general model of how markets work, before he starts thinking in Pt. 2 about how specifically capitalist markets work. Capitalism is unique in being the first class system to be so thoroughly mediated by market relations, so we can’t understand capitalism until we understand how markets work more generally, but these are still two different tasks.

And one reason I’m belaboring these points is that so much contemporary Marxology rests on the assumption that everything I’m saying right now is wrong. So, for example, if you read Michael Heinrich’s How to Read Marx’s Capital, you’ll see him starting by making great hay of Marx saying in the paragraph of Ch. 1, that “the wealth of societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails” appears as “an immense collection of commodities,” from which Heinrich somehow gleans that Marx’s analysis of commodities is only supposed to apply to commodities as they exist under capitalism. And then, several times later in the book Heinrich takes time to ‘remind’ readers, all on the basis of that first paragraph, that Marx’s analysis of commodities is only supposed to apply under capitalism. This, I have to say, drives me crazy as a reader of Heinrich because that paragraph very obviously entails no such thing.

Similarly, in his book Marx’s Inferno: The Political Theory of Capital, William Clare Roberts claims that Marx’s theory of commodities and value in Pt. 1 only applies under capitalism. He says, and I find this really fascinating, that, Marx is “committed” to the claim that commodities didn’t have values in pre-capitalist societies, like—keep this example in mind!—ancient Athens.

And one more example:

In Soren Mau’s book Mute Compulsion: A Marxist Theory of the Economic Power of Capital, he says that Engels thought Pt. 1 was about a “pre- or non-capitalist” scenario of “simple commodity production” whereas we sophisticated 21st century interpreters know better and we see that it’s totally not that. Mau flatly states that “Capital is about capitalism from the very first page.”

And then later on he says that in Pt. 2 of Capital the autonomous units of commodity production in Pt. 1 were “revealed to be” capitalist firms.

So, the Heinrich/Roberts/Mau view can I think be fairly summed up as:

Disputed Claim #1: Marx’s theory of commodities and their values only applies to commodities that exist in capitalist economies

And I want to argue now against both that claim and a recognizable watered-down variation of it that you often see floating around this literature, which is:

Disputed Claim #2: Whether or not the generalities about commodities and their values in Pt. 1 are supposed to apply to pre-commodity production, Marx’s view is that any society that includes sufficiently widespread commodity production conforming to that description is definitionally capitalist.

I’m calling that a watered-down variation of #1 rather than just its own unrelated thing because the two converge on the idea that Pt. 1 works out to being Marx’s theory of capitalism. I disagree.

As I’d read him, Marx differentiates historical stages like feudalism, capitalism and socialism—I’m very comfortable with what some Marxists consider to be the grave heresy of “stagism”—primarily by which class relations bind the immediate producers to whoever’s extracting surplus labor from them. So, I don’t think Marx identifies capitalism with commodity production either in the Disputed Claim #1 sense or the Disputed Claim #2 sense.

And it’s worth pausing to ask—why anyone would care about this?Like, it’s all very well to be a Marx nerd and to want to get every detail of Capital right for your next reading group, but is there anything more than that at stake?

I think there might be, at least for those of us in the overlap region of the Venn Diagram of (a) thinking Capital is the most enduringly insightful book every written about capitalism, and (b) acknowledging that any kind of socialism that we know how to design at this stage in history would have to include a role for markets as a coordinating mechanism in at least some parts of the economy, even if the autonomous units of production being coordinated in those sectors are worker-controlled firms.

The calculation problems economists started arguing about decades after Marx died are real problems. The pathologies of Soviet-style planning were very real and very bad and can’t be reduced to their computers not being as good as ours yet, and I’m (while this is a subject for another time) I’m just not convinced that a new and radically democratic form of socialism would be able to get past those pathologies any time soon. Obviously if future technological developments or logistical breakthroughs deliver fully marketless fully automated luxury communism, I’m for that! But, that’s at least not in the cards yet, and I want our advocacy of socialism to be an advocacy of a real thing we already know how to implement it. I don’t want socialism to be like a lot of leftists’ commitment to “prison abolitionism,” by which they really just mean that they don’t like prisons and they have a vague normative hope that some day in the distant future we’ll somehow or other find ourselves not needing them any more.

I want it to be something that, if we could get past all the political obstacles and actually win the class war, we’d know how to implement, I do think that means biting the bullet on some market mechanisms. So, one way of framing what could be at stake here (or part of what’s at stake), is whether, if we’re clear-eyed about all of that, Capital can still be a useful intellectual resource for thinking through what capitalism is and how to get past it. It’s not clear whether it would be, at that point, if Marx’s analysis doesn’t leave any room to distinguish between markets in general (at the level of generality at which Part One is pitched) and capitalism per se.

Of course, one thing that’s absolutely not in dispute is that Marx was very far from being a market socialist. In a footnote early in Capital, for example, he says that the labor-time certificates in Robert Owens’s version of communism would no more be money than a theater ticket is money, and Marx definitely presents that as a good thing. He absolutely hoped and expected that when the workers’ movement overcame capitalist property relations they’d be able to simultaneously overcome commodity production and institute some sort of wall-to-wall rational economic planning, so that we’d then have a society without market chaos, the epistemic distortions of commodity fetishism, and the rest. (And again: There really are many good normative reasons to want to advance to a marketless form of socialism if you can have that without unacceptable tradeoffs in terms of economic functionality. Democracy and equality are plausibly better served by society-wide economic planning where everyone in society has a say than by workplace democracy within separated firms, for example.) But none of this is the same question as whether Marx equated capitalism and commodity production (or commodity production of the kind described in Part One of Capital.Here are two pretty straightforward reasons to think that Marx wasn’t committed to any of that:

First, take a look at his discussion of Aristotle in Section 1.3. Marx loves Aristotle so much that if you’d only ever heard of Aristotle from reading Capital you could be forgiven for thinking the man’s full name was “Aristotle, the Greatest Thinker of Antiquity.” And he quotes a passage in the Nicomachean Ethics where Aristotle comes very close to anticipating Marx’s own argument in section 1.1 that the value of a commodity has to be understood in terms of the average socially necessary labor time it take to produce it (once we’ve abstracted away from the particulars of different labor processes to find the common thread of universal human labor). Aristotle gets to the point of seeing that it would explain a lot if there were some common element of all commodities that underlay their exchange-value ratios, but despite his great genius he doesn’t make the final conceptual leap.

So, why didn’t he?

The fascinating thing here is that Marx never once so much as hints that it’s because he doesn’t think commodities in Aristotle’s Athens had labor-time values. In fact, everything about his language pretty straightforwardly implies that they did. Marx says that Aristotle was unable to “decipher” the “secret” of value and then later that Aristotle was unable to “extract” the “fact” that value is universal labor, all of which is incomprehensible if you don’t think there was a reality already there waiting to be discovered. And Marx’s explanation of the failure isn’t remotely ontological—not remotely about what did or didn’t exist in the ancient Athenian economy, I mean—but purely epistemological. He said that human equality had to “acquire the permanence” of a “fixed popular opinion” for anyone in a given society to make the conceptual leap that the labor being done by everyone was, in some ultimate sense, all the same thing.

He claims that Aristotle was blocked from making this leap by the ideological blinders of a slave society. The idea seems to be that citizens of such a society had to deeply convince themselves that slaves were a different category of beings that free workers, or else they wouldn’t have been able to stay sane in that social environment. And whether or not you think that this is a plausible suggestion about the history of philosophy, a plausible diagnosis of Aristotle’s disagreement with Marx about value, there’s just no part of Marx’s explanation that hints at (or is even compatible with) the idea that commodities didn’t have values in ancient Athens.

And then we can turn from Marx being able to detach commodity production from capitalism in *pre-*capitalist contexts to him detaching those two things when thinking about hypothetical post-capitalist scenarios when we look at his discussion of John Stuart Mill.

Marx actually mocks Mill for saying that if commodity-producing collectives of workers collectively owned their own means of production, capitalists would still exist, because workers would be their own capitalists. This is precisely the kind of thing that some contemporary figures who think of themselves as super-duper Marxists would say—that if you’re engaged in commodity production, you’re therefore doing capitalism, even if you’re doing commodity production plus workers’ control of the means of production, that this would just be a sort of collective capitalism.Well, that’s not Marx’s view! Some people think it is, on the basis of a much more ambiguous passage in an unpublished notebook that Engels threw into Vol. 3.

But, here’s exactly what he says, starkly and clearly, at the end of Ch. 16:

Mill might just as well have said that the worker who advances to himself not only the means of subsistence but also the means of production is in reality his own wage-labourer, or, indeed, that the American peasant is his own slave, because he does forced labour for himself instead of doing it for someone who is his master.

Again, Marx is not a market socialist. He doesn’t expect or hope that the scenario Mill has in mind, where autonomous worker-owned units engage in market competition, is what would come to pass after capitalism. Even so, I don’t see an intellectually honest way to conclude that Marx thought that such a set-up would be a form of capitalism.

Thanks for reading Philosophy for the People w/Ben Burgis! This post is public so feel free to share it.

From Philosophy for the People w/Ben Burgis via this RSS feed