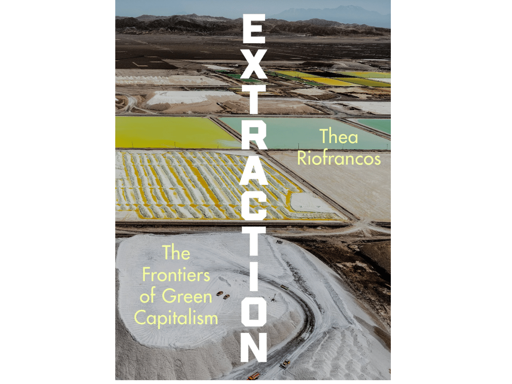

A new book by Thea Riofrancos called, Extraction: The Frontiers of Green Capitalism, shows how the push for critical minerals like lithium and cobalt is creating a new wave of mining while perpetuating old patterns of exploitation and environmental destruction. She writes:

The energy transition is not a peaceful bridge, but a crucible where past, present, and possible futures collide.

She traces the story to the immediate aftermath of World War II. During the post-war years Western oil giants, namely Standard Oil and the Seven Sisters, controlled nearly all Middle Eastern and Venezuelan crude and in doing so established a global system of dependency. The “Seven Sisters” group included:

Standard Oil of New JerseyStandard Oil of New YorkRoyal Dutch ShellAnglo Persian Oil CompanyStandard Oil of CaliforniaGulf Oil, andTexaco

Capitalism, colonialism, and the race for lithium

Riofrancos places lithium at the centre of the green energy transition. The lightweight metal is crucial in modern society, powering rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles, smartphones, and countless more electronic devices used today. Ironically, the foundation for this technology, as she traces, was laid in the 1970s by Exxon when it formed part of Seven Sisters under its previous name, Standard Oil of New Jersey.

Commercial lithium extraction in the US, she contends, is enabled by the 1872 General Mining Law. The legislation still governs lithium mining throughout America, and yet the supposed landmark law lacks environmental safeguards and water protection. As Riofrancos explains:

[it was] explicitly designed at the time of its passage to transfer Indigenous lands to white settlers.

Chile is also central to the story of lithium extraction, as told by Riofrancos, as well as the political changes that rocked Chile during Salvador Allende’s three-year stint as president.

just as copper was central to Allende’s vision of democratic socialism, so, too did it prove pivotal to the coup that deposed him on September 11, 1973.

When Allende moved to nationalise the copper industry, seizing the property of American mining firms, the US response was swift and severe. The Nixon administration hit back severely, leveraging funding strikes and blocking aid — placing Chile’s economy in a chokehold. This created, the author argues, an opening for the ascent of General Augusto Pinochet and his dictatorship (1973 – 1990).

State-owned Codelco now mines just a quarter of Chile’s copper. Meanwhile, firms like SQM control the Atacama’s lithium. Riofrancos notes SQM is “already infamous for its links to the Pinochet dictatorship.” She adds that its “scandals were so many that it boggles the mind.”

The Atacama Salt Flat, which boasts one of the the world’s richest lithium deposits, is now the heart of Chile’s lithium rush. The power conglomerates maintain hold these resources was on full display at the 2019 industry convention. Major producers — SQM, Albemarle and Tianqi — fiercely rejected a plan by London Metal Exchange (LME) to standardise the lithium futures market, fearing greater transparency and a level playing field among lithium producers. Still, beneath these theatrics, local communities remain an afterthought.

More of the same: UK Minerals Strategy

A new UK Critical Minerals Strategy is imminent. Think tanks and environmentalists, including the government-adjacent Royal United Services Institute have demanded a more “muscular” policy. However, based on the 2022 plan proposed by the then-Conservative Government, their strategy perpetuates existing patterns of extraction and inequality. It repackages the old model of extraction that treats the Global South as a resource frontier — more of the same.

The flagship company Pensana abandoned the UK in favour of the US whose incentives tipped the balance in their favour.

However, the core problem was revealed in its plan: the mine is in Angola, but the refinery and jobs were planned for Hull. This shows the UK strategy still treats Angola as a source of raw materials while trying to keep the valuable processing in the Global North, repeating a colonial division of labor where the South provides the resources.

Riofrancos warns that while lithium is needed for climate solutions existing efforts must be decoupled from colonial practices of extraction and exploitation to avoid greenwashing. Though she concedes that there are no easy answers to the current extraction race.

Still, the current path of green extraction empowers the same corporate behemoths. A just transition offers a way out of the centuries-old cycle of extraction. This means less mining, not more; robust public transit over endless electric cars, and a circular economy that prioritises material reuses materials. Above all else, it must restore power over resources to local communities.

Featured image via Thea Riofrancos

By Nandita Lal

From Canary via this RSS feed