Photo by Jametlene Reskp

“Bend down low let me tell you what I know” – Bob Marley

The word “lowdown” has all kinds of meanings. Not a whole lot of them good ones. One exception is in relation to jazz, where we might say, “Come on, Miles, give us the lowdown,” meaning favor us with the relevant information to feed the soul. Lowdown suggests down-and-out, street-level survival, fits and starts, and maybe even homelessness. Like a Vietnam vet who’s seen Apocalypse Now one too many times and got hisself good and lost, or an itinerant Lived Experience Expert (LEE) on a barking mad memoir tour. Lowdown maybe suggests the kind of poverty and suffering and pointless desire that drove the Buddha, riding high on his royal elephant limousine one fine privileged morning, to form a nihilistic religion, albeit on the sunny side of the darkness otherwise all around us. But lowdown is also loaded terminology. The Urban Dictionary, known for its straightforward definitions, provides some synonyms to consider:

Beneath repute; skeevy; skanky; shady; sordid; nasty; dirty; contemptuous; deceitful

The buyer’s realtor tried to make a lowdown dirty offer.

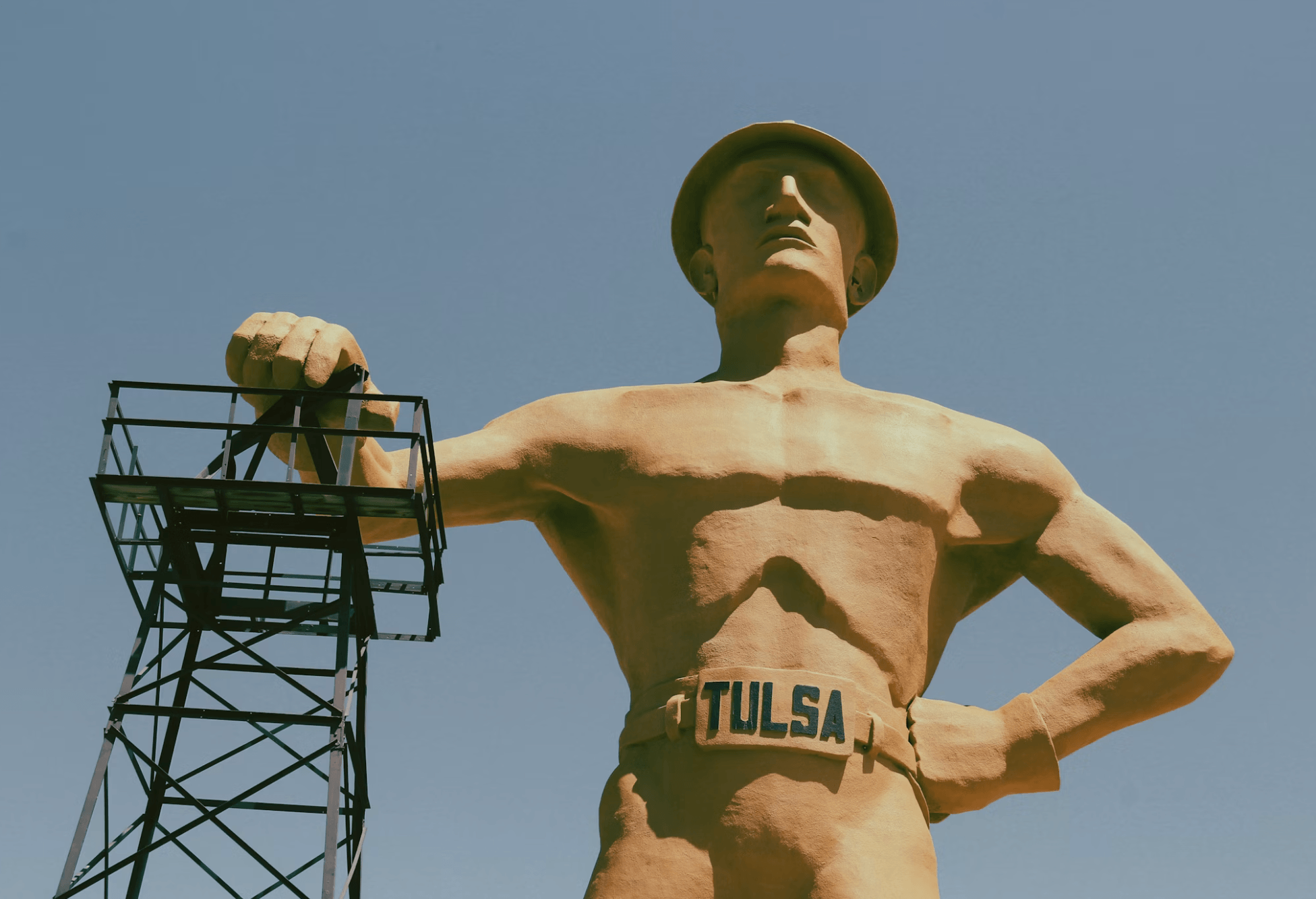

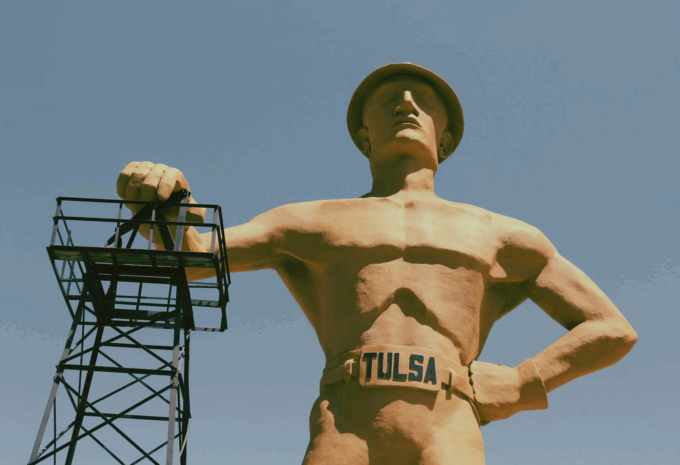

I don’t know about your experiences, reader-responder, but I have felt lowdown at times in my life. I have suffered. Jesus, have I suffered. And believe me, I know all about the “Why have you forsaken me” question. I have been careless with my caring, similar to Lee Raybon, a Tulsa bookstore owner who became a reporter; he cannot tolerate the corruption surrounding him and decides to investigate a murder, believing that exposing the darkness may help eliminate its evil. Even if it means risking everything he has left of his precarious life, he is determined to bring some sanitization to the situation in his impoverished hometown, which is populated by down-and-out cowboys and ind’gens. Lee is a reader and writer surrounded by mostly illiterates and cultural underachievers.

Lee Raybon, the bookstore owner and freelance journalist alluded to above, is the protagonist of a new streaming 8-part series—The Lowdown, starring Ethan Hawke. It’s set in an edge neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma. It’s a lonely-lookin’ decrepit little space in time. American Indians who are off their reservation, poor whites, and some colorful token Blacks coexist in this area, creating a feeling that an underworld of white Christian corruption is present. The dreaded clans. IMDB describes the premise of the series thusly: “A determined bookstore owner in Tulsa moonlights as an investigative journalist, digging into local corruption. When his reporting uncovers sinister connections, he must protect both his family and the truth.” But it’s way more laid-back and comically scummier than that. Lee quotes from books—he loves Jim Harrison, novelist (Legends of the Fall) and memoirist—and suggests to a book-browser (a ghost of the story’s murder victim) in his shop that he read The Man Who Fell to Earth by Walter Tavis.

Relatively recently, Hawke has cameoed in the role of a deserting father who returns many years late to meet his teenage daughter in an episode (S3E9) of the ind’gen reservation series Reservation Dogs (2021-2023). More recently, he stars in Blue Moon (2025), about the life of musical lyricist Lorenz Hart and his struggle with alcoholism and mental illness leading up to the premiere of Oklahoma! These roles have no doubt enriched and informed his representation of being a scrivener of the anthropological complexity of energies that wrestle around him. It is advantageous that he maintains a tolerant and easygoing attitude and that his compassion and sense of humanity are among his greatest strengths.

Some townsfolk refer to Lee as “the man who knew too much,” but we discover, with the episodes, that he doesn’t know what he doesn’t know until the end. In reality, as Lee uncovers details of the murder, his journalistic curiosity about it is treated as quaint and unusual. Quaint and unusual was the way some of us saw those writers who wrote for the MassPIRG newspaper that carried the weight of the burden of good citizenship, brought to us first by Ralph Nader (who inspired PIRG with his 1971 book, Action for a Change). A Black friend queries Lee’s devotion to the cause at one point and receives back Lee’s earnest desire to shed light on the cover-up in order to make the world better. “Oh, you’re the tragedy of the white man who cares.”

The cast is excellent for what amounts to a slow-burn story among folks burdened with little nuance. People are just getting by, trying to stay afloat, in a world drowning in its own bullshit. Ethan Hawke is joined by Kyle MacLachlan as Donald Washberg, the murder victim’s brother and a politician running for the governor’s office. Jeanne Tripplehorn plays Betty Jo Washberg, Donald’s ex-wife, who seduces Lee for information. Ryan Kiera Armstrong as Francis Raybon, Lee’s teenaged daughter who lives with her mom, plays a delicate doll-eyed girl whose innocence and devotion to Lee help keep him tethered and resistant to bitterness. Keith David as Marty Brunner, Washberg’s confidante and bodyguard. Scott Shepherd as Allen Murphy, a local contractor and mob associate. And an assortment of Native Americans, one or two, like Waylon (played by Cody Lightning), who hang around the bookstore, gesturing rudely to passersby, and Lee’s bookstore assistant Samantha (played by Kaniehtiio Horn from the Mohawk Nation) hasn’t been paid in some time.

There’s a trailer for the series embedded below, but it’s a bit tricky to describe the synergy involved with the characters and the setting, which makes this biography and drama comedy work so well. The People’s Wikipedia accurately and adequately describes the pilot of the series this way:

“In Tulsa, Oklahoma, self-styled “truthstorian” and bookseller Lee Raybon has published an exposé about the powerful Washberg clan; Dale Washberg, the black sheep of the family, hides a letter before being found dead of an apparent suicide. Investigating the Akron real estate development group, Lee is approached by a stranger named Marty and is later attacked by skinheads Blackie and Berta. At Dale’s estate sale, Lee discovers the letter, which reveals Dale hid more letters about a family conspiracy in his collection of Jim Thompson novels. Lee convinces antiques dealer Ray to acquire the collection for him in exchange for a stolen Joe Brainard painting, while tabloid editor Cyrus agrees to publish Lee’s follow-up article and gives him a gun for protection. Dale’s brother Donald is running for governor, and Lee deduces that he is having an affair with Dale’s widow, Betty Jo. Blackie and Berta kidnap Lee to deliver him to Akron contractor Allen Murphy, who kills the skinheads instead, unaware Lee is in their trunk. Freed by Marty, who has been following him, Lee flees in Blackie’s car and discovers a large envelope of cash.”

Power to the People, right on!

Lee gives the impression that he might be a bit nuts. Missing some screws. Another loveable loser, like Jeffrey Lebowski. Yes, he finds a bundle of cash in the vehicle of his kidnappers, who have been offed by a mob associate, and immediately begins spreading the wealth around, paying old debts and some overdue salary to Samantha, and chore payments to the curbside ind’gens out front, etc. It doesn’t seem to occur to him that someone might come looking for the money. Something has happened to him to make him this way. His quirkiness may have cost him his marriage. His daughter keeps a watchful eye on his doings and acts as a reality check for his decision-making that is poignant and true.

Also, worth noting about the plot outline above, the tabloid mentioned is essentially an x-rated flesh publication with ads for meetups at pleasure points. This is a funny realization, knowing that almost everyone in the town has read the exposé in the skin rag. One recalles the heyday of Playboy magazine that would tackle issues too hot for the mainstream media to handle.

The Lowdown brings to mind the film Killers of the Flower Moon, which details the real-life theft of Osage Nation oil by white thieves. The Lowdown conjures up the social milieu of the Osage boomtown, built and maintained as a place for newly enriched Osage Indians to essentially go to purchase and conspicuously consume goods from all over the world with their riches—cars, jewelry, furniture, clothing, and white men’s services. (Remember how we laughed for years at the schemers who approached the Clampetts in The Beverly Hillbillies to help them spend their oil money? Jedddd!). Flower Moon tells us the story of the Osage Nation’s forced removal from Kansas and relocation to Oklahoma, where removers hoped they’d find hardscrabble land and a miserable life ahead. But just under the Osage land was a massive deposit of oil, and overnight it became perhaps the richest society in the world. Then after white people heard of their discovery, they moved in, and the secondary wave of westward migration helped the natives deposit some of their money in white men’s banks and rent their services. David Grann, author of The Killers of the Flower Moon, described the population this way:

“Once, the tribe’s enemies had battled them on the plains; now they came in the form of train robbers and stickup men and other desperadoes. The passage of Prohibition had only compounded the territory’s feeling of lawlessness by encouraging organized crime and creating, in the words of one historian, ‘the greatest criminal bonanza in American history.’”

The land was essentially lawless, as wealthy Osage individuals hired “lawmen” to safeguard their interests. What we get in The Lowdown is a fast-forward into the future after all of the riches are gone, like some wealthy paper mill town now completely gone bust and filled with government-subsidized poor people dependent on food stamps, who can’t afford to move on; you hang on. The original corruption Lee writes about has to do with a previous generation’s theft of Osage land, but Lee sees the corruption as still alive and festering.

At the same time, The Lowdown also recalled the delicate characterizations painted in the streaming series Reservation Dogs, Sterling Harjo’s previous streaming project. Harjo, a Muscogee descendant, does a laudable job presenting a kind of silence that emanates from Native Americans. In Reservation Dogs, which is about the lives of some teenagers who hang out together sharing the dream of one day escaping from reservation life, children are seen with a troubled quietude that is full of dignity and beauty, even at times heartbreaking, as when the gang gets up to mischief and struggles with the moral consequences of their actions. Reservation Dogs features an offbeat police officer who is more of a guardian of peace than a pursuer of malfeasance and who is always gentle with the children. Lowdown also depicts some unusual cops who act childishly and casually insult Lee. In The Lowdown, Francis, Lee’s daughter, similarly possesses a still point that Lee reads carefully and steadies himself by. “Dad, you can tell me the truth.” Francis is there to remind him not to lose his own integrity in fighting the corrupt forces of the world. Harjo’s framing of children as fragile and soulful offers a perspective this viewer rarely sees in contemporary depictions of children, one that predates their exploitation by our culture.

Likewise, Harjo’s depictions of “little persons” (dwarves, wince) are drawn with respect, egalitarianism, and humor, in both Reservation Dogs, which features rap-spouting twins riding high-bar banana-seat bikes, and in The Lowdown, where Peter Dinklage plays Wendell (“the richest dwarf in the world,” according to TikTok—wince). In his only scene, Wendell, who is Lee’s cocky former business associate, assists Lee with a crucial detail in his investigation. (As a side note, Queen Goss tells us that Dinklage is universally hated among “little people” for saying dwarves should not be hired by Hollywood to play dwarves— wince.) Psssst. Pass it on.

The tragedy of the white man who cares. This is not quite a leitmotif, but after two thugs kidnap Lee for his journalism, it is almost a prophecy. The series doesn’t say, “Don’t be caring”—alas, no; but be careful out there, it’s a wild world and shit happens. This is particularly true in Oklahoma, where the former dominant white population resides. “Ain’t nothing sadder than a white man who cares,” his Black friend with the triple X tabloid tells him, “but okay, I’ll print your story.” Somehow or other, we’re told the story spread nationally like a textually transmitted disease.

The name Harjo is a war title and surname derived from the Muscogee word háco, meaning “active” or “crazy.” And his Natives are generally more than just a little restless. In Reservation Dogs, there is a ghost who shows up at the reservation from the castration event known as Little Big Horn, who died after falling off his horse; he visits the kids, talks trash, and lets out little battle squawks. Crazy horse he had. Stupid white man.

Harjo also conjures up another Harjo: Joy, a citizen of the Muscogee Nation and poet, who went on to become the first Native American poet laureate of the USA. She reads here a wonderful excerpt from her children’s book of poems, Remember (2023):

One can imagine Lee reading such a poem to his sleepy daughter Francis; although neither is a Native American, both are, like the Natives, people. Power to the People, Right On!

The Lowdown is an offbeat crime drama with humor. Sterling Harjo is an outstanding teller of tales who comes from a tradition where the telling of story is still not only appreciated but vital to the oral culture that formed it. You may find yourself wanting to have a look at Reservation Dogs or see Killers of the Flower Moon through a different lens.

The post Corruption and the Tragedy of Carin appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed