The Great Enclosure by Caspar David Friedrich

Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital. This week in The Times I wrote an entirely frivolous column on the joy of neologisms. I also spoke to the NPR show Think about the death of reading.

Thanks for reading Cultural Capital! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

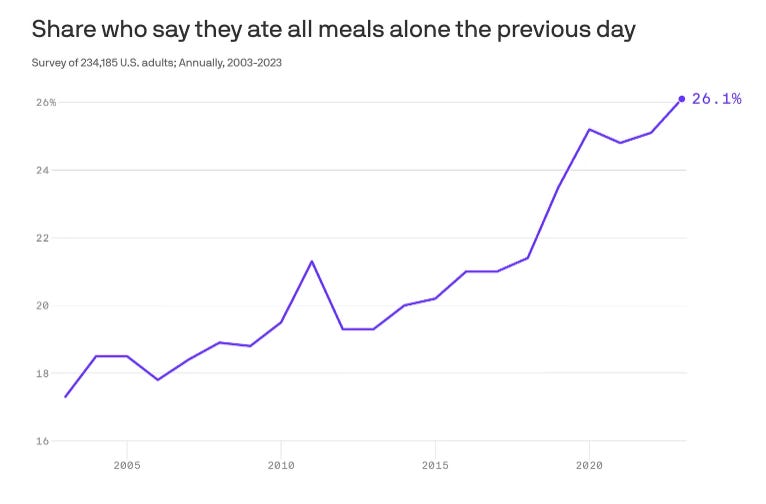

The monks in the casinoA couple of years ago Derek Thompson introduced me to the idea of the “secular monks”, young single men who lead lonely ascetic lives of self-improvement: eating alone, going to the gym alone, working from home alone:

When porn seems less fraught than sexual partners, and when late night parties seem lower status than early-morning Pilates, a toxic asceticism is spreading throughout American life. No, the problem is not loneliness. The problem is that we’ve forgotten how to feel lonely in the first place.

In this interesting new piece Thompson argues that many young men might be better described as “monks in the casino”. They live solitary and boring lives in the physical world but in the virtual world they are surrounded by addictive casino-like screens:

“We talk a lot about the ‘male loneliness crisis’ but in my estimation we don’t talk enough about the ‘male suckerfication crisis,’” Max Read wrote. Young men are “continuously cultivated” by their media to become dupes and suckers “in service of the profits of an ever-expanding roster of gambling and gambling-adjacent industries

A lot of young men are addicted to pornography or video games or, increasingly, online betting:

Roughly half of men between the ages of 18-49 have a sports betting account. In New Jersey, nearly one in five men aged 18-24 is on the spectrum of having a gambling problem

And so a bleak paradox develops. The real-world lives of these young single men are uneventful, risk free and monk-like: no relationships, no friendships, no parties, no drinking, no sex. But their virtual screen lives are highly risky and charged: extreme pornography, dangerous gambling scams, heroic virtual adventures in games.

Cancel Culture FlashbackThe new BBC Radio 4 documentary about the infamous cancellation of the author Kate Clanchy is a vivid reminder of how crazy and terrifying Twitter was back in 2021 (of course it’s crazy and terrifying in a much worse way now). I wrote about the documentary in The Times here.

Though I was never remotedly Clanchey-ed, the documentary brought back some unpleasant memories.

In my early years as a journalist I caught a lot of flak on Twitter. For a while a reliable way to go moderately viral was to screenshot the headline of my latest article with my provokingly baby-faced byline picture and scoff at whatever idiocy Marriott had come out with now.

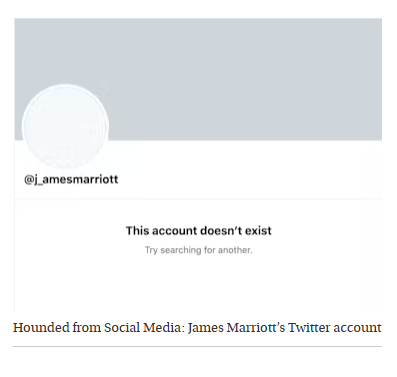

On a few occasions I was moved to leave the site for a few days in the hope things would cool off in my absence. A rookie error! Leaving strikes observers as a dramatic overreaction and you discover you’ve been “hounded from Twitter”.

One of my houndings was amusingly (in hindsight) written up as an article:

the unfortunate Marriott was firstly bombarded by insults and criticism, and then, at the time of writing, driven off Twitter altogether. One blogger’s reaction was to call the piece, which he had not read in full, ‘a pointless exercise in ageism and middlebrow whatiffery’, and concluded ‘Marriot’s [sic] article is behind a paywall so I don’t know whose views he solicited, but perhaps he should expand his circle of acquaintances, and broaden his reading horizons. Or just shut the fuck up.’

The unfortunate Marriott

I would like to say I didn’t care about all this but I did find it intimidating. Being dragged on Twitter was both humiliating (all your friends and colleagues were watching) and frightening (you were always aware people’s reputations really were destroyed this way).

The experience of a 2021-style pile-on which seemed at the time like an essential feature of the internet no longer quite exists. Social media has fragmented (right wingers on Twitter; lefties on Bluesky) and no single platform seems to be able to assemble the critical mass of life-destroying condemnation. Perhaps we will look back on cancellation as an ephemeral phenomenon of the early internet.

What’s it like to be sixteen in 2025This long report on the media environment of sixteen year olds from the think tank Demos is written in an upbeat tone but I found it dystopian:

On average, they watch nearly five to six hours of video a day, much of it on mobile; scrolling, swiping, and absorbing without pause. Young people are not following one person’s ‘ideology’.

They follow and are ‘influenced’ by tens if not hundreds of creators. Their feeds are shaped by algorithms, not loyalty. They scroll from a MrBeast giveaway to a Bonnie Blue thirst trap, then onto a Jordan Peterson rant about how Mark Carney is the devil reincarnated, a News Daddy news clipping, or a HasanAbi protest livestream, all within a matter of minutes.

One student said it best: “I don’t follow one person. It’s more like, whoever the algorithm throws at me.” Another said: “Even if you don’t want to see certain people, they’ll still come up. You don’t choose who influences you.”

The report says that Andrew Tate — endlessly referenced in media articles about teenage boys — is no longer relevant.

“We are told Andrew Tate is still the big thing. He’s not. Bonnie Blue is.” You’d have thought the disappearance of Tate would be a good thing but this actually seems to be a bad development:

Many creators slip easily between everyday vlogging and explicit adult material. This is reshaping how young people think about sex, intimacy and their own self worth…Bonnie Blue’s appearance on ITV’s This Morning shocked viewers but it also forced mainstream audiences to confront a reality that young people already take for granted (Wright, 2024).

Sex work is not hidden away on obscure corners of the internet anymore; it sits just a click away from TikTok or Instagram. In our listening sessions, young people frequently referenced encountering OnlyFans content, often unintentionally. A student in Sheffield explained it clearly: “It’s literally everywhere now. You can be scrolling on Instagram and suddenly you’re watching someone who’s basically an OnlyFans model. It’s not even something you choose.”

Thank god I’m old (despite the byline picture).

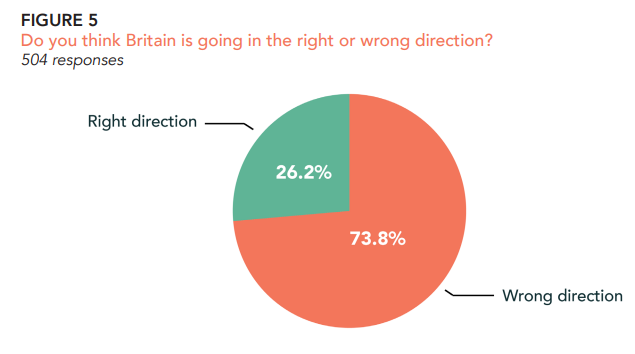

Well, at least our young people are optimistic

The problem with critical thinkingI agree with Daisy Christodoulou’s argument against the fashionable idea that children need to be taught “critical thinking” rather than boring old facts.

The evidence that teaching critical thinking skills actually improves critical thinking is dubious at best:

In a 2007 article, the cognitive scientist Dan Willingham noted that over the last 20 years, programmes designed to teach critical thinking had become very popular, but they were not very effective. He concludes with the following:

“Can critical thinking actually be taught? Decades of cognitive research point to a disappointing answer: not really.”

He makes the same point about the limitations of teaching maxims.

“If you remind a student to ‘look at an issue from multiple perspectives’ often enough, he will learn that he ought to do so, but if he doesn’t know much about an issue, he can’t think about it from multiple perspectives.”

The problem is that you can’t just teach abstract “critical thinking” that is magically disembodied from the world. How are you supposed to think critically without facts?

I think history teachers in the UK have similar experiences of the challenges of trying to teach students to evaluate truth claims with general principles. Are sources written by individuals more or less reliable than ones written by governments? Are sources written by eyewitnesses more or less reliable than ones written centuries after the event? Are sources written for publication more or less reliable than private diaries or letters?

The answer in every case is “it depends”.

You can’t evaluate the world if you don’t know anything about the world.

How new words boost IQIn my column about neologisms I was glad to be able to mention one of my favourite recent facts which I encountered in Steven Pinker’s book The Sense of Style.

The spread of new words from the fields of science and technology may have helped boost IQ in the twentieth century:

In a very real sense such neologisms make it easier to think. The philosopher James Flynn, who discovered that IQ scores rose by three points a decade throughout the twentieth century, attributes part of the rise to the trickling down of technical ideas from academia and technology into the everyday thinking of laypeople.

The transfer was expedited by the dissemination of shorthand terms for abstract concepts such as causation, circular argument, control group, cost-benefit analysis, correlation, empirical, false positive, percentage, placebo, post hoc, proportional, statistical, tradeof , and variability. It is foolish, and fortunately impossible, to choke off the influx of new words and freeze English vocabulary in its current state, thereby preventing its speakers from acquiring the tools to share new ideas efficiently.

Until next week!

James

From Cultural Capital via this RSS feed