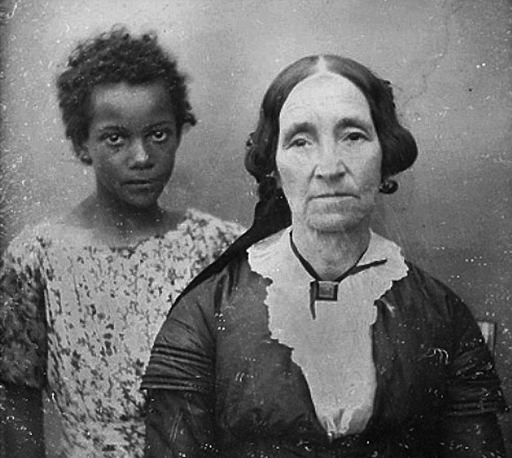

Portrait of an older woman in New Orleans with her enslaved servant girl in the mid-19th century – Public Domain

In Slavery in the British Empire and its Legacy in the Modern World (Monthly Review Press, 2025), Steve Cushion lays bare the underreported history of that vile institution. To this end, he makes the case, persuasively, that enslaved African labor for centuries is at the root of financial and industrial wealth, then and now. In other words, chattel slavery was central to the rise of modern capitalism, ecologically and economically, with all that follows from those aspects of social life.

Cushion broadens and deepens the Marxian critique of Eric Williams’ seminal Slavery and Capitalism (Andre Deutsche, 1944). Cushion writes: “An aim of this book is to situate the past crime of enslavement and the modern-day dangers of climate change within the business practices that place profit before people.”

That is, the modern business enterprise of an employer class owning and controlling its labor force via the wages system flows from the past exploitative and extractive commerce of owning living human beings as capital.

In brief, the ruling class’s theft under the British Empire of unpaid African labor for reasons of capital accumulation and class power propelled the rise of financial and industrial development for corporations and the wealthy. To drive his thesis, Cushion unpacks the money-slavery legacy of the Drax Family in Britain. Its exploitation of enslaved Africans in Barbados, cultivating sugarcane, paved the way for robust profits to flow into their English pockets, in part to buy up commoners’ land available from their eviction resulting from the Enclosures.

Numbers matter. In the first chapter, Cushion introduces a relative income and wealth measure per person over time in the business of enslaving Africans. The past amounts compared parenthetically with today’s figures are staggering—multiple trillions of dollars. Cushion is a historian, not a macroeconomist.

The corporate-government nexus is central to the early days of this coercive social relationship. Three examples are the Royal African Company, the East India Company and the South Sea Company. Accordingly, the fascist trend underway today has a history rooted in early capitalist labor exploitation. Cushion dispels the notion of an economy separate from a polity, the so-called free market of buyers and sellers absent an active government role. That role evolves from a protectionist state to help the British and American slavocracy to a “free trade” regime of maximum capital mobility.

The political economy of the British Atlantic Empire and plantation management, chapters two and three, respectively, articulate in part the role of the ecology, or Nature. The connections between New England and the West Indies, trafficking of enslaved Africans, and indigenous genocide, soil depletion and scientific management, and last but not least, Christian slavery, cohere into a totality.

Law and order, the title of chapter 4, takes up the character and form of the state and its role in extracting a surplus from the enslaved labor force in the British colonies. The business of slavery required an active role from the government to, for instance, protect capital investment with force.

The role of creditors receives abundant treatment in Cushion’s book. Consider his fifth chapter, Finance and Industry. He writes: “The financing of industrial development cannot be separated from the more general banks, investment houses, lenders, finance companies, real estate, brokers, and insurance companies, commonly known as the financial services industry.” Subsequently, he fleshes out relevant and significant historical details and links to the institution of coerced and unpaid labor.

Resistance of workers to slavery outside the homeland of British imperialism (the enslaved) and inside (the waged), is a stirring theme in Cushion’s book. For example, a little-known example of international solidarity between English cotton workers and enslaved Africans in the American South during the Civil War deserves a younger and wider audience. I, for one, failed to learn this remarkable story of workers’ cross-border solidarity until I was an adult.

Further, the revolt of the enslaved Africans in the colony of Demerara in Guyana sent shockwaves there and in England. Meanwhile, enslaved African women, workers in ways big and small (reproductive, especially), also played central roles as liberators. “Just as enslaved women were an integral part of the workforce,” according to Cushion, “so they were also central to the opposition to enslavement, frequently playing an important role of encouraging a culture of resistance. Although the male chauvinism and white supremacy of contemporary chroniclers have meant that women’s roles were often neglected, women and men reacted to enslavement, punishment, and torture in similar ways, from everyday resistance to outright rebellion.“

Current demands for slavery reparations from governments in the Caribbean to compensate the descendants of African enslavement are picking up steam. Social movements can and do change the consciousness of people, with the pro-Palestine solidarity movement in the U.S. shifting public opinion away from blind support of Israeli apartheid. Expanding the power of the ruling ideology via institutional indoctrination is a priority among the social ruling class. Pushing back in dissent are scholars such as Cushion. His new book is a wind in the sails of the slavery reparations movement for historical justice.

The post Situating Slavery’s Legacy appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed