On their first day guarding a mall in Minneapolis, the men met in a warehouse on the outskirts of town at 4 a.m. to get “kitted up.” They put on flak jackets and masks. Some had military fatigues. Their boss, Nathan Seabrook, wore a walkie-talkie headset. He packed two pistols and a weapon that dangled from his three-point sling—it could have been a pepper-ball launcher, but in the early morning darkness, it looked like an assault rifle. A patch on Seabrook’s vest displayed the acronym of his company: CRG.

The idea for Conflict Resolution Group emerged in 2020 after a local police officer choked George Floyd to death on camera. Nationwide, protests erupted. Some gave way to rioting, as angry demonstrators smashed windows, looted businesses, and set fire to buildings. In Minneapolis, the 3rd Police Precinct burned on national television. Amid the civil unrest, fears of political violence increased—especially among business owners. As an armed forces veteran and Black man from Minneapolis, Seabrook sought to offer a solution for those wanting a feeling of safety amid chaos. He hired men like himself to provide a private service: For enough money, you could call in your own troops.

In his 50s, with a linebacker frame and salt-and-pepper beard, Seabrook had experience. He fought in both Iraq wars: as a soldier in Operation Desert Storm in 1991 and as a military contractor during the American occupation in 2003. In the late aughts, he did a stint as a police officer at a Veterans Affairs hospital, then spent the 2010s working in “high-threat protection,” guarding United Nations dignitaries across Africa and the Middle East.

In 2018, when Seabrook moved back to Minneapolis, there wasn’t much of a market for military combat experience. But the city changed drastically after the summer of 2020. The post-Floyd unrest, which left more than 1,000 buildings in Minneapolis damaged, cost the city over $350 million by one estimate. Much of the scarring was on Lake Street, a commercial corridor that stretches across the south side of the city from the Mississippi River, past the 3rd Precinct station, all the way to the Seven Points mall in the Uptown neighborhood.

With his hometown at the center of an uprising, Seabrook feared the worst. In his mind, Minneapolis now resembled an overseas war zone. It needed men like him on patrol. The private security industry is dominated by big conglomerates like Allied Universal and GardaWorld; Seabrook created CRG as a boutique firm. Some of his employees had résumés like his: American veterans from foreign wars. One was purportedly a “green badger,” the nickname for contractors who have worked for intelligence agencies like the CIA. The group was more Blackwater than Paul Blart—and decidedly overqualified to guard a struggling shopping center.

Even Seabrook agreed. “Never in a million years,” he later said, could he have imagined putting his former combat experience “into play in Minnesota, of all places.” But everything had shifted. In a now-deleted promotional video, Seabrook introduced CRG as uniquely suited for a new American landscape of “uncertainty,” where “no place is truly safe.” He promised potential clients that his company would provide the “tools, resources, and highly trained personnel to make that uncertainty go away.”

A private security contractor installs razor wire.Chad Davis

But that’s not how things played out. Seabrook and his crew often were the uncertainty, as revealed by a Mother Jones investigation consisting of more than a dozen interviews, scores of court documents, and police and military records. The reporting shows how a lack of accountability for overseas military contractors can boomerang when veterans put their skills “into play” in the homeland.

During his time leading CRG at Seven Points, Seabrook and his team allegedly intimidated, threatened, and surveilled protesters, all while operating as a heavily armed force. (A protester even claims one employee brandished a gun to push her off the property while shouting obscenities.) Seabrook developed individual a series of intelligence briefs on some activists, using information scraped from the internet. To justify such tactics, he inflated the threat the protests posed to public safety, labeling the participants “antifa” and likening them to jihadi terrorist groups he’d encountered abroad. On at least one occasion, an activist said Seabrook warned that he did not want to have to shoot protesters.

“They’re importing a conflict mindset from Iraq and Afghanistan that dehumanizes their surroundings.”

CRG also coordinated directly with the Minneapolis Police Department—even as Seabrook was viewed with skepticism by some police officers. In a typical message, among at least a dozen he sent, Seabrook informed police he had “helped to identify members of an ANTIFA cell” at Seven Points. Some officers, despite cooperation, seemed unsure about CRG. Commenting on work at another site where CRG was hired later in 2021, a ranking officer reportedly described Seabrook in an internal communication as “diabolically manipulative.”

As President Donald Trump deploys armed forces to major cities based on fears of disorder—and after the issuance of an executive order declaring antifa a domestic terror organization—the role CRG played in Minneapolis can be seen as foreshadowing. A group of men in plain clothes, tactical gear, and face coverings patrolled an American city with minimal oversight. Soldiers were deployed on questionable grounds—using tactics from wars abroad—to a town’s floundering business district. Citizens, treated like insurgents, faced men eager to impose law and order, brought in with promises of a payday.

This is what can happen when soldiers are for sale.

Until the summer of 2021, Seabrook was virtually unknown outside the secretive world of security and military contractors. That would soon change.

In April that year, as the city tensed amid the trial of Floyd’s killer—former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin—a different law enforcement official in a nearby suburb shot and killed a 20-year-old Black man named Daunte Wright. A few months later, the city was rocked yet again. On June 3, seven unmarked police vehicles surrounded the car of a 32-year-old Black man, Winston Smith, atop the Seven Points parking garage. Officers involved in a US Marshals-led fugitive task force had planned to arrest Smith for missing a sentencing court date. For years, details of the events were disputed. But in 2025, footage from Smith’s phone was released. It showed him grabbing a gun from his center console and raising it before officers shot and killed him. (Prosecutors deemed the officers’ conduct legal but admonished their lack of de-escalation).

To many locals, Smith’s death, on the heels of Wright’s and not long after Floyd’s, felt like a recurring nightmare. “For the past couple of years, the only thing we have seen is people getting choked out like George Floyd, Daunte Wright getting shot in their car,” Kidale Smith, Winston’s younger brother, told me. “We just kept seeing the same thing over and over.”

In the days and weeks following the Smith shooting, demonstrators congregated next to Seven Points. Near the parking garage where he was killed, spray-painted messages proliferated. One read: Mpls still hates cops. Winston Smith was assassinated. How many more? Red paint was spread on a street leading to the garage. One night, during a string of marches, a group of protesters smashed windows and looted two pharmacies and a T-Mobile store. Another night, protesters set a dumpster on fire and wheeled it into the street.

Graffiti in Uptown, Minneapolis protesting CRG.Chad Davis

Compared to the widespread rioting of 2020, these disturbances were small-scale. But the city’s temperature had changed. In the intervening year, 200 MPD officers had left or were unavailable for service—many cops had taken disability leave for PTSD from the protests. Gun violence was on the rise. And much of the city had not been rebuilt. Local politicians feuded over the future of law enforcement as Minneapolis became the epicenter of a movement to defund the police.

Ten days after Smith’s death, the protests took a dark turn. A drunk driver sped at 80 mph down Lake Street, crashing into barricades and killing a woman, Deona Knajdek. (The driver later was tried and sentenced to 20 years in prison.) After the death, the protesters abandoned the street and established a memorial garden in a vacant lot next to the parking garage. It was a way to say, “We’re not leaving here; we’re not forgetting about what happened,” protester Rachel Lawrence told me.

Initially, Seven Points—owned by the Chicago-based group Northpond Partners—seemed sympathetic to the memorial. The mall publicly supported the garden as a place for “healing.” But soon after, there was a shift. Seven Points accused protesters of property destruction, arson, noise violations, and blocking access to the mall entrance. (A spokesperson for Seven Points did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

It was around this time, a month after Knajdek’s death, that a Minneapolis cop named Patrick Reuben reached out to Nathan Seabrook about work at the mall. Seabrook had just wrapped up a job for CRG’s debut client, attorney Jerry Blackwell—the special prosecutor who secured Chauvin’s murder conviction. Reuben mentioned a new opportunity: Seven Points needed extra security.

A CRG vehicle parked outside of Seven Points Mall.Chad Davis

Seabrook got to work researching the site and drafting a plan. Titled Operation Peaceful Garden, it was written in the form of a military operation order and was modeled on a mission he’d conducted in Libya. (Seabrook had worked for an unspecified client, commandeering an abandoned oil facility, likely following the US-backed ouster of Muammar Gaddafi.) Seven Points was a smaller field of play. In the plan, CRG would evict protesters and set up a base in the parking garage where Smith had been killed. Then, Seabrook said, he and his team would make sure the people maintaining the memorial to Knajdek and Smith “didn’t come back.”

The proposal was aggressive. But Seabrook felt it was needed. He would later explain, when challenged on his work that day, that he respects people’s right to protest—he had fought to protect it abroad. But in his eyes, these were not protesters: They were “agitators” affiliated with “antifa,” and the encampment was their “shrine.” With this in mind, Seabrook foresaw a “high threat operation,” as he drafted Operation Peaceful Garden. The “individuals living in the make shift camp will fight back using both wood clubs and rocks,” the plan said, and “team members should prepare for demonstrators to be armed.” Seabrook told Seven Points management that there was no way his team was going in without their own firepower.

In the wee hours of July 14, 2021, CRG, backed by Minneapolis police, came to push out the protesters. A community violence prevention group called We Push for Peace was also there to help de-escalate a potential confrontation. Despite that, Seabrook’s team came clad in tactical gear, carrying zip ties, with glow sticks hanging from their necks. Videos from the raid show protesters and a We Push for Peace employee reacting to CRG’s heavily armed operatives with alarm and confusion.

“People stopped coming to any kind of protests simply for the fear of the fact [CRG] were there.”

Seabrook’s men encountered no armed resistance. In fact, it was just the opposite: It was their intimidating presence that provoked an uproar. Onlookers wondered why it looked like troops were guarding a parking garage. Reports of the encounter spread quickly. Independent news outlet Unicorn Riot noted Seabrook’s military history and the former soldier’s heavy-handed approach.

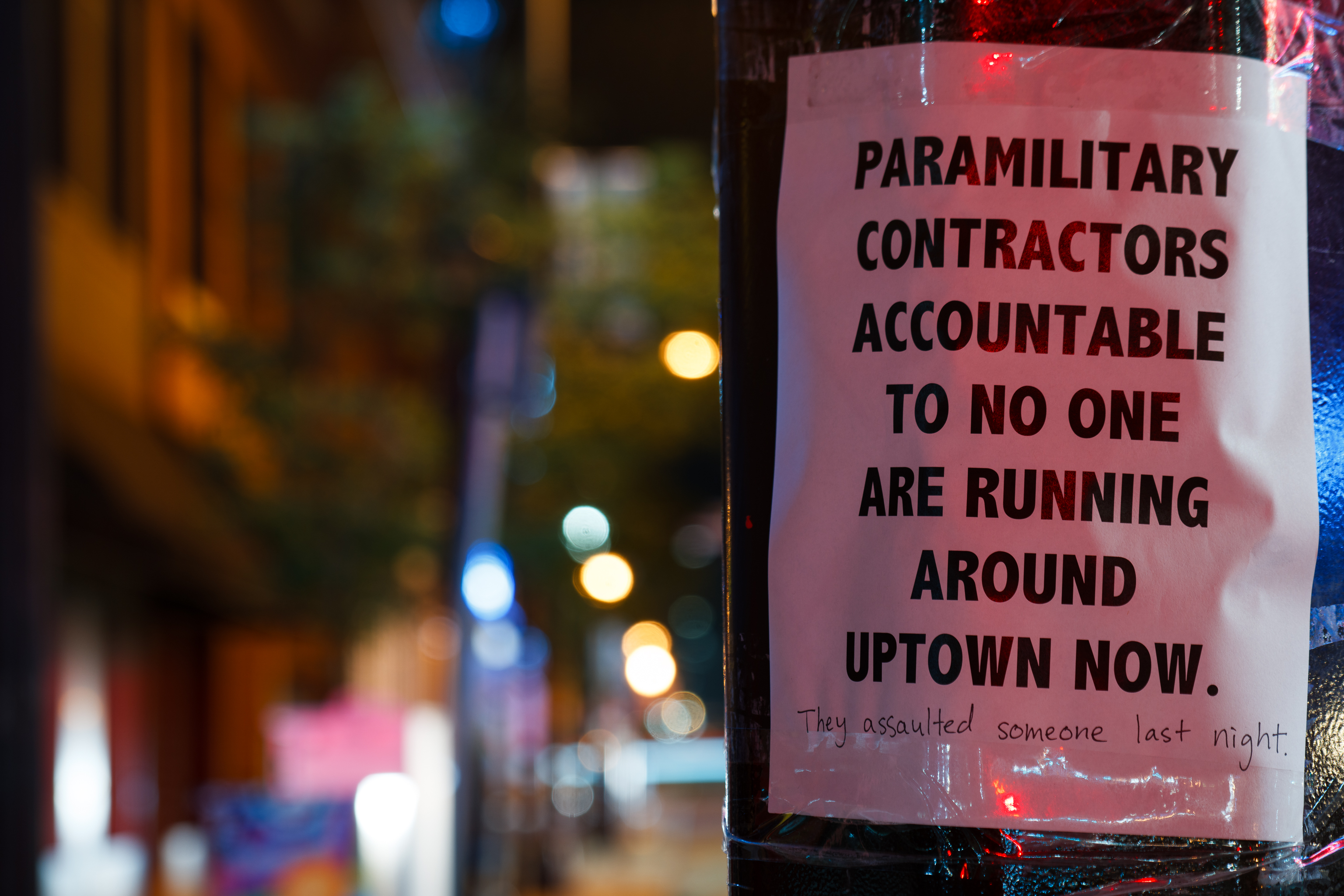

The next week, local activists held a press conference outside Seven Points condemning the “international mercenaries stomping around Minneapolis,” as CRG team members watched from their command perch atop the parking garage. In the weeks after the garden eviction, Seabrook’s men remained on the mall grounds, now fenced, while protesters gathered on a nearby sidewalk.

It was then that things started to get “creepy,” as one protester, Alli Riebel, told me.

At the time, Riebel lived close to Seven Points. She had been around the garden and protests before. When Knajdek died, Riebel was among the group trying to give aid.

In the days leading up to the raid, Riebel was out of town on a camping trip. But the day after CRG’s initial raid, Riebel came to retrieve some of the supplies that hadn’t been thrown away. Seabrook approached her car and asked whether she planned to bring her cat, Miley, with her the next time she went camping. The implication was, Riebel believed: I know what you do in your free time. I know what your vehicle looks like. I know the name of your cat. “It’s never fun to be in your neighborhood and know you’re being watched,” she told me. The experience made her fear for her safety, and Riebel ultimately moved out of state.

There were other signs that Seabrook was watching protesters closely. Through a records request, Mother Jones obtained a proprietary “intelligence packet” Seabrook created on a local activist and sent to Minneapolis police. Part of a series of intelligence briefs, including “threat assessments,” “daily analytical summaries,” and “flash reports,” it was branded with green CRG letterhead and made claims based on social media posts. There was another case of reported surveillance-based intimidation, too. At one mall demonstration, MIT Technology Review reported, CRG blasted a song from loudspeakers—it was an original piece that had been recorded and posted online by one of the protesters.

Protest signs were placed in Uptown, denouncing the presence of CRG.Chad Davis

The tactics proved effective. “People stopped coming to any kind of protests simply for the fear of the fact [CRG] were there,” Lawrence told me. People were afraid of speaking out: “If you did, then you are vulnerable to being antagonized by this group that we really don’t know much about,” she said.

CRG also, in Lawrence’s view, seemed to be working in partnership with the police. And police did talk with Seabrook to coordinate work, reports show. But some officers had doubts. “Guys, we’re going to have to talk more about Nathan Seabrook and his company,” a police lieutenant wrote in an internal email obtained by MIT Technology Review. CRG’s long guns, heavy vests, and skull-patterned masks, the officer noted, made them look like “heavily armed vigilantes.” Another lieutenant said in an email that Seabrook was “diabolically manipulative” and wanted to “lay rotting animal parts” in an alley to scare off potential miscreants. Still, no one stopped CRG from working at the mall.

“This exchange was an internal communication between staff and was not an official statement of MPD or the City,” MPD spokesperson Garrett Parten said in response to a list of questions. He added that the department “interacts daily with many different private business owners, managers, and security personnel throughout the city” and that the intelligence reports CRG sent were “evaluated and processed based on its content,” like all crime tips the department receives. “Currently, MPD has no interaction with Conflict Resolution Group (CRG) and has never had a contract with them,” Parten said.

In October 2021, there was a vigil at the property commemorating the four-month anniversary of Smith’s death. Kim Wooster, a Navy veteran who had been serving as a protest medic since 2020, was there that night wearing scrubs. CRG employees stood atop the parking garage, shining floodlights down on the protesters. During the memorial, Seabrook’s workers played recordings of a Martin Luther King Jr. speech.

Amid an ensuing shouting match, Wooster told me, one of the men pointed his weapon directly at her. (An incomplete video of the interaction shows an employee armed with an assault rifle wave his gun toward her briefly.) “They have no emotional control,” she said. “They have no de-escalation techniques. They’re operating as though they are mercenaries.” It is a matter of time, the veteran recalls thinking, before one of you shoots someone.

CRG’s work at the mall continued, as did Seabrook’s emphasis on surveillance. CRG appeared at the mall multiple times, far past when protests died down, even up to the summer of 2022. In 2023, Seabrook appeared in an advertisement for “mobile surveillance trailers” alongside a local liquor store owner, who said he’d hired CRG based on a police officer’s recommendation. In the video, Seabrook boasts about using cameras to build cases on potential criminals and turning them over to MPD. He added that he’d soon upload “AI software” to his camera systems to “start mapping individuals.”

In May 2023, I also received a worrying message about Seabrook from John Nobles, a volunteer and activist who supports the city’s homeless encampments.

“Dude I’m freaking out,” he wrote.

Nobles told me that he had been shopping for supplies at Home Depot when a man grabbed him by the shoulder and turned him around. The aggressor introduced himself as Nathan Seabrook of Conflict Resolution Group.

Private security surveils protesters in Uptown, Minneapolis.Chad Davis

“I have been watching you on Twitter,” Nobles recalled him saying. “This is going to get settled now.”

Nobles scurried away, but the encounter left him shaken. “Because he’s close to the police, there’s nothing I can do,” he told me. “I’m afraid that he and his goons are going to pull me into an alley and beat me.” Nobles did not report the incident to police.

“Any assessment by MPD of private security businesses would be independent and unaffected by any personal relationships the businesses may have with individual officers,” said Parten, the MPD spokesperson.

During the 2020 summer protests, people around the world took inspiration from what they saw happening in Minneapolis. But less discussed was what happened in the aftermath. In 2021, Minneapolis cops had all but stopped doing their jobs. A Reuters investigation found the department had adopted “a hands-off approach to everyday lawbreaking.” In response, private security firms stepped into the void.

The industry was already thriving even before the pandemic hit. But it took off after 2020. In other cities, the same trend occurred as in Minneapolis: more private cops. An annual industry survey by consulting firm Robert H. Perry & Associates noted that “unprecedented times”—political upheaval, racial tensions, mass demonstrations, mass shootings, and a looming recession—were driving a boom in the private security sector. Pandemic-fueled spikes in gun violence and property crime were also contributing factors, said Steve Amitay, who runs the trade group National Association of Security Companies.

“If you think that society is going to turn around and all of a sudden get a lot more polite and respectful,” Amitay said, “I think that genie is out of the bottle.” The number of private security guards working in the US has doubled over the past 20 years, according to the Security Industry Association. Per the Perry survey, the sector was worth an estimated $36 billion in 2023, up from $20 billion roughly a decade earlier.

As the industry has expanded, military veterans have come home and sought work. Nathan Seabrook was indicative of this period. On trips home from abroad, he dipped into the growing niches where veterans, security contractors, firearms enthusiasts, and survivalist preppers steel themselves for future collapse—or, in their lingo, for when SHTF (shit hits the fan).

In 2016 and 2017, Seabrook appeared several times on a podcast called Warrior Life, often as “Contractor X.” In one interview, he claimed to have fought off a murderous mob of 40 people that surrounded his car in an “undisclosed African hot zone,” armed only with a machete. These hot zones, Warrior Life host Jeff Anderson wrote in a blog post accompanying the interview, were typically in an “armpit of the underworld.” Your American city could be next, he warned.

In 2020, after the pandemic isolated people in their homes, gun sales skyrocketed. Protesters took over the streets of US cities. In 2021, a violent mob ransacked the US Capitol, hoping to reverse the election results. Outlets of respectable thought published serious contemplations of a second US civil war. As Seabrook narrated in his now-deleted CRG promotional video, 2020 was America’s SHTF moment, and he was ready to help.

Experts say it is not a coincidence that a figure like Seabrook would emerge at the same time that a generation of military contractors began seeking out fresh opportunities as the US wars in the Middle East wound down. “They’ve learned a lot over the past 20 years about how to operate,” said Michael Picard, an independent researcher and co-author of a 2022 Transparency International report on the “hidden costs” of private security and military companies. “The US government has never taken the initiative in regulating them domestically or abroad.”

When there’s a market for force, Picard explained, contractors have a financial incentive to overstate the danger of political upheaval. “They’re importing a conflict mindset from Iraq and Afghanistan that dehumanizes their surroundings,” he said. “That leads to more employment and better contracts.”

Around the time CRG launched Operation Peaceful Garden, Seabrook appeared on the podcast Fearless Mindset, hosted by Los Angeles-based security firm owner Mark Ledlow. Their conversation touched on Seabrook’s time in Libya and how that experience compared with his work in Minneapolis, which Ledlow said “had become like a Third World country.”

It was surreal, Seabrook concurred, to see his hometown turned into a “shithole,” almost like the bombed-out cities he’d seen overseas. Companies like his were filling the “vacuum” for understaffed police departments, he said. “We’re having the highest resignation rate for police officers across the country,” Ledlow chimed in. “Who’s going to be keeping the streets safe after they’re all gone? It’s going to be guys like yourself.”

Those guys like Seabrook had returned from overseas with special experience and unexamined pasts, the products of a new paradigm in armed conflict. The recruitment of former soldiers and deployment of military gear by US police departments was already alarming, underscoring a sense of the police as an occupying army and citizens as internal enemies. But there has been a new wrinkle of late. Contractors, who had little oversight abroad, come home to work as private security personnel, and there are few checks on these workers in the US. Neither the police they coordinate with nor the licensing bodies for private security firms have reliable means to scrutinize what these private soldiers may have done overseas.

An armed member of CRG private security surveying a protest at Seven Points Shopping Mall.Chad Davis

Hired guns are as old as warfare. But the corporatized private military firm is a modern invention, a consequence of the end of the Cold War. The 2003 Iraq invasion was the coming-out party for these new companies, which put an “already thriving” industry of military contractors “on steroids,” industry expert Peter Warren Singer has written. By 2008, there were more contractors in Iraq—around 190,000—than US troops.

Some contractors during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan had deals with the Department of Defense, others with the State Department, others with USAID. Hundreds of firms sprouted “like mushrooms after a rainstorm,” former Washington Post war correspondent Steve Fainaru explained in Big Boy Rules: America’s Mercenaries Fighting in Iraq. Their operations ranged from highly professional, with “boards of directors and glass offices,” he wrote, to others that looked like “scarcely more than armed gangs.”

Fainaru described them as men who carried themselves like cowboys patrolling the frontier, in customized vehicles straight out of Mad Max. They did not seem to be part of any military chain of command. “You had tens of thousands of people on the ground who were operating under their own rules,” he told me.

In 2014, Seabrook published a book about how to become a military contractor abroad, Infidels in the Garden of Mesopotamia. He had gotten into the work 10 years earlier, when the industry was in the midst of a gold rush. Here was how you could join, too. The Wild West approach was attractive to many, the money incomparable. One contractor Fainaru interviewed said he made less than $2,000 a month as an Army sergeant; working as a private military contractor in Iraq could fetch you $500 to $2,000 a day.

No surprise then that Seabrook jumped on the “bandwagon,” as he put it. He worked stints for firms that no longer exist, like DEH Global and Securiforce. He also became a manager at an infamous company, Crescent Security Group.

Crescent was like “the Kmart of private security,” Fainaru wrote in Big Boy Rules. “I could never figure out what their minimal hiring standards were.” Founded in 2003 by Franco Picco, an Italian-South African businessman, the firm was based in Kuwait and became “notorious” for corner-cutting and a reported willingness to venture into places most would not, and for less money.

While embedded with Crescent, Fainaru heard rumors about employees smuggling weapons and liquor in homemade “stash boxes” concealed inside trucks. It was “the military without the rules,” Fainaru told me. “The whole thing made me really uneasy.”

A common task for private firms like Crescent was accompanying supply convoys on the long highways from Kuwait across the border into Iraq. Without rules of engagement, Crescent crossed lines, Fainaru reported. After a roadside bomb attack, employees “fired their automatic weapons preemptively whenever they passed through the town” where they had been hit, according to a Washington Post report by Fainaru. A former employee told Fainaru that many other incidents were never reported to the military. “Crescent, as a going concern,” Fainaru wrote, “was not even remotely safe.”

One incident became notorious. In November 2006, Crescent operatives were on a routine mission escorting 37 empty trailers from Kuwait to Tallil Air Base in southern Iraq when they stopped at what they thought was an Iraqi police checkpoint. There, they were ambushed by 30 gunmen. Before help could arrive, five contractors had been abducted.

Seabrook had left Crescent by this time, but he was still intimately connected to the situation. One of the kidnapped men was Crescent medic Paul Reuben, who in 2003 left his job as a police officer in a Minneapolis suburb and decided to work in Iraq on the recommendation of a childhood friend: Seabrook. (His twin brother, Patrick, is the Minneapolis cop who would later connect Seabrook to Seven Points.)

During trips home to Minneapolis in the early aughts, Seabrook was a regular at the gun shop of Mark Koscielski, as were the Reubens. Seabrook would regale Koscielski with his war stories as he worked on his firearms. But the shop owner sensed that Seabrook had come to understand that as a private contractor, the rules did not apply to him.

When Koscielski told Seabrook that one of his desired gun modifications was illegal, Seabrook pulled out a Common Access Card military ID with a GS-15 rating. Seabrook, Koscielski told me, said he acquired the ID fraudulently, and the GS-15 designation enabled him to “go into any military warehouse and check out any equipment I need.”

Another former Crescent employee, Ben Borrowman, corroborated Koscielski’s claims. Borrowman told me that he had been interviewed around 2007 by Army investigators looking into Seabrook and Crescent. He said he told the officials that Seabrook used his access card to get into US bases and take equipment that contractors were not allowed to possess. “Bottle of whiskey later,” Borrowman explained, “you never know what you carried off.”

Seabrook allegedly sold some of the guns to Crescent owner Picco for use by the firm, Borrowman said. “I didn’t realize it was all illegal until [the investigators] called me,” Borrowman told me.

Documents I obtained through a public records request show that the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division (CID) looked into Seabrook. The almost 200-page investigation accused him of fraudulently obtaining at least two military Common Access Cards with GS-15 clearance by providing false documents. In total, the CID investigators alleged that Seabrook stole $1.7 million worth of government-owned weapons and property and provided false statements to investigators. The report does not include a comprehensive account of what Seabrook was accused of stealing, but it mentions a myriad of weapons and vehicles, including four M2 machine guns, two MAG 58 machine guns, three armored personnel cars, and a Humvee. One witness told investigators that Seabrook had “an extensive collection of automatic weapons in his Minneapolis residence.”

In January 2008, federal authorities searched Seabrook’s home. No automatic weapons were found. But a “fraudulently obtained CAC card,” along with several computers and digital hard drives, were seized as evidence, according to a complementary report from the Defense Department inspector general’s office that was included in the record request. Later that year, the investigation was referred for prosecution to the Defense Criminal Investigative Service, an arm of the inspector general’s office.

An office representative told me that after receiving the case from Army CID, the office referred the case to the Minnesota US attorney’s office, which declined to prosecute. A spokesperson for the US attorney would neither confirm nor deny this, but said the office did “not have any records or information on this individual.” When I recently returned for a final comment, the US attorney’s office said it could not consider my inquiry because of “the current lapse in appropriations,” due to the government shutdown.

Somehow, the case against Seabrook seems to have never gone anywhere, despite the extensive investigation. He was never formally prosecuted or charged with any crime. But that does not change how Borrowman views him. He described Seabrook as a “tyrant” and “megalomaniac” who was always testing the limits of what his subordinates were willing to do. “He would tell me to do things that jeopardized security and jeopardized people,” he said of Seabrook’s work as a manager at Crescent. “It was a shit show. Once you ended up in his sights, you became a target and he would manipulate you to get whatever he wanted.”

Seabrook didn’t mention his work with Crescent Security Group in his application to the Minnesota Board of Private Detective and Protective Agent Services. In fact, the board expedited his application because of his status as a military veteran. By December 2020, Seabrook and CRG were open for business.

Richard Hodson, chair of the board, told me that the application requires a complete statement of employment history and confirmed that Crescent was not listed in Seabrook’s application. “If he’s leaving out a significant security-related employment history, that would be something that would probably be worth a review,” Hodson said.

The ease with which someone with Seabrook’s track record was able to transition from a war zone to domestic security speaks to a lack of oversight and communication among local, state, and federal regulatory bodies. That he was accused of serious violations but never charged or prosecuted, and none of the law enforcement agencies involved would explain why, raises questions of just how broad the culture of impunity extended during the so-called war on terror.

When I told former Crescent employee Borrowman that Seabrook had been hired by a mall in Minneapolis to get rid of protesters, he laughed hysterically and brought up the movie Paul Blart: Mall Cop. He then adopted a more serious tone. “He doesn’t know how to do something like that,” Borrowman said. “He doesn’t know how to disseminate people in a peaceful manner. And he will use threats and duress to achieve his goals—at all costs.”

Nathan Seabrook, founder of CRG, on patrol.Chad Davis

Nathan Seabrook declined my request for an interview. Neither he nor his attorney answered a detailed list of questions about his past. (In a letter in response to my interview requests for this article, Seabrook’s attorney also threatened to sue for defamation. He did not follow up on an additional request for clarity around a potential suit.)

Still, I did manage to speak to Seabrook once.

In October 2023, Seabrook testified in a Minneapolis courtroom about his time with CRG at Seven Points. He wore a dark blue suit with faint orange stripes, a white shirt, and brown dress sneakers. His hair and beard were neatly trimmed. Dark-rimmed rectangular frames sat across his weathered face. He looked sullen but resolute. In his quarrels with Minneapolis activists, Seabrook had filed two unsuccessful restraining orders. Now, he was filing a lawsuit.

A local yoga instructor, Hayley Saccomano, alleged that on CRG’s first night at the mall, Seabrook had punched her in the head. She sued him, saying the alleged assault caused a brain injury that dramatically affected her cognitive faculties. Seabrook denied her allegations and countersued, claiming battery and defamation. He alleged that Saccomano maced him after he ordered her off the mall’s property and then defamed him and CRG on social media.

During the four-day trial for Seabrook’s defamation suit, his attorney tried to correct what he claimed was a wrongheaded narrative spread by malicious actors online: namely, that a former mercenary led a paramilitary security firm that had assaulted an innocent, unarmed woman. Under oath, a competing narrative took shape: Seabrook was an Army veteran who’d risked his life serving his country, a widower who returned to the Twin Cities to raise his kids after their mother unexpectedly passed, and a Black small-business owner trying to maintain public safety in the city that made him. Seabrook did not talk about Crescent Security Group on the stand; he only said that he had “worked as a security contractor protecting diplomats in Baghdad.”

In Seabrook’s account, the weeks and months following Operation Peaceful Garden were catastrophic for his life and business. He was doxxed and threatened, he told the court, and sent his 20-year-old daughter—who backed up Seabrook’s trauma in testimony at the trial—to live with out-of-town relatives. In a deposition taken before the trial, Seabrook had said an unidentified group attacked his employees with a BB gun, Molotov cocktails, and “black powder” bombs. Business got harder. CRG’s insurance rates went up. The company lost potential clients. And that wasn’t the worst of it, he said. His voice started to quaver. He paused, took off his glasses, and cleared his throat. There were online accusations that he and his company were part of the racist extremist group the Proud Boys. He began to cry. It stung him, Seabrook said, because his grandfather was killed by the Ku Klux Klan. “I don’t care how tough you are, [it] really affects you. It affects your psyche,” he said, choking back tears.

On the stand, Seabrook compared what he’d experienced in war zones to what he’d experienced in Minneapolis, “with people taking information and posting it online.” He repeatedly used the word “agitator” to describe the Seven Points demonstrators. When CRG arrived at the mall that July morning, they were confronted by agitators. There were multiple attempts of “agitator overrun.” When asked to clarify the difference, Seabrook responded that protesters follow rules and agitators make trouble.

As we awaited the verdict, I approached Seabrook outside the courtroom to ask for an interview. He told me nobody deserves to die as Winston Smith did. He said the whole ordeal had depleted him. He repeated the story of his grandfather’s killing, and his voice began to tremble as though he were going to break into tears once more. Then he said he didn’t want to talk to me anymore.

The next day, Seabrook won parts of his suit. Saccomano had claimed in an Instagram post that CRG employees had assaulted and given brain injuries to multiple people, not only her. During the case, Saccomano also admitted to macing Seabrook. The jury found that Saccomano had committed civil battery, with damages of $5,000. They did not find her guilty of defamation against Seabrook, but did find her liable for defamation against his company, CRG, for $17,500. The assault suit Saccomano brought against Seabrook was later settled out of court. As part of the agreement, she was barred from discussing the case with the press.

After its 2021 stint at Seven Points, CRG continued to operate. Seabrook has refrained from issuing public statements in response to the accusations against him and his company. The exception was one interview with reporter Liz Collin, best known as the producer of The Fall of Minneapolis, a documentary that claims George Floyd wasn’t murdered. The headline on that story read: “Mpls. security expert says leftist groups use Taliban-like tactics to intimidate opponents.”

Otherwise, Seabrook kept his online profile to a minimum. Then, Elon Musk purchased Twitter in 2022. Since then, Seabrook has had stints of prolific posting on the platform, renamed X. From a verified account, using his full legal name, Seabrook has, among other things, justified ICE’s detention of Tufts University student Rümeysa Öztürk; posted memes likening Democratic Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz to Mao Zedong; defended Kyle Rittenhouse, who shot and killed two people during a protest over a police shooting in Wisconsin; taunted the former vice chair of the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, who’d tweeted about patronizing a bakery near Seven Points; replied “Hi” to an OnlyFans model; told at least two X users he’d had sexual relations with their mothers; and congratulated a man named Mike Glover, who had just announced that a domestic violence case against him had been dropped (“Hope your well Mike, great news. This is Nate from Libya.”).

Meanwhile, CRG seems ready to reenter the fray. On CRG’s X page, there is a retweet of Blackwater founder Erik Prince’s call for private security firms to carry out the Trump administration’s plan to deport millions of immigrants. In their masks and civilian plain clothes adorned with tactical gear, the federal ICE agents conducting deportation raids look a lot like Seabrook and his team did in the midst of Operation Peaceful Garden. It’s the same informal uniform worn by many of the private military contractors he worked alongside in Iraq.

The company has a new redesigned website. Whether “a natural disaster, civil disturbance, or executive security concern,” it promises, CRG will be there to “respond with speed, efficiency, and unwavering professionalism.” To illustrate this, the firm advertises its work at the protests over Winston Smith’s killing, safeguarding “a large facility from various groups, maintaining order and securing critical infrastructure.”

After the memorial garden was cleared out, Kidale Smith, Winston Smith’s younger brother, went to meet the Seven Points protesters and pass out fliers to raise awareness about his brother’s killing. He heard about CRG and Seabrook. “I’m not quick to judge,” he told me. “So I went to talk to the guy.”

Over a meal at a Thai restaurant in the mall, Seabrook made a good first impression. “The point he was trying to get across is that [CRG was] a Black-owned organization—he’s for Black people,” Kidale recalled. Seabrook promised to help Kidale get in touch with a retired FBI agent he knew to help investigate his brother’s case. He also said that if Kidale could get the other protesters to leave, he’d allow him to visit the site of his brother’s death to grieve without disturbance.

But then the tone changed, Kidale said. Seabrook took out his phone and showed him pictures of different protesters: “He’s like, ‘Well, see, the thing is, they’re antifa. These people are terrorists and they’re trying to terrorize Uptown. I don’t want to have to shoot nobody’…He’s got this demeanor where it’s like, If you don’t do exactly what I say, I’m gonna do what needs to be done.”

Kidale was baffled by the asymmetry. “Listen, I’m out here. Nobody out here has weapons. Nobody out here has guns,” he recalled telling Seabrook. “He wants to look like the good guy. And the best way to look like a good guy is to label everybody else a bad guy.”

Once the protests dissipated, Kidale never heard back from Seabrook about the proposed help. But when Kidale and his family went to visit the parking garage on the one-year anniversary of his brother’s death, CRG employees were there. In a video Kidale posted on Instagram, a man dressed in tactical gear and a skull mask that conceals his face orders the mourners to leave.

In the end, Kidale said he felt used. “The minute [the protests] were gone, it was like it never happened, business as usual,” he told me. “I felt like a fool…like it was better when people were just up there lighting dumpsters on fire.”

From Mother Jones via this RSS feed