Illustration: Pablo Delcan

Last winter, the federal government released the results of its semi-annual reading and math tests of fourth- and eighth-graders, assessments that are considered the most authoritative measure of the state of learning in American elementary and middle schools. In nearly every category, the scores had plunged to levels unseen for decades — or ever. On reading tests, 40 percent of fourth-graders and one-third of eighth-graders performed below “basic,” the lowest threshold. A separate assessment of 12th-graders conducted this past spring — the first since schools were shuttered by the COVID pandemic — yielded similarly crushing results. Many graduated from high school without the ability to decipher this sentence. How can I assume that? The test asked them to define the word decipher, and 24 percent got it wrong.

“You can’t believe how low ‘below basic’ is,” says Carol Jago, a former public-school teacher who has served on the board that oversees the test, which is called the National Assessment of Educational Progress. “The things that those kids aren’t able to do is frightening.” Fourth-graders were presented with a multiple-choice question about a passage from the children’s book The Tale of Despereaux, asking why the main character, a mouse, decides not to eat a book. Nearly 30 percent could not pick the answer (“He wants to read it instead”). A similar proportion of eighth-graders failed to come up with the following sum:

12 + (-4) + 12 + 4 = _______.

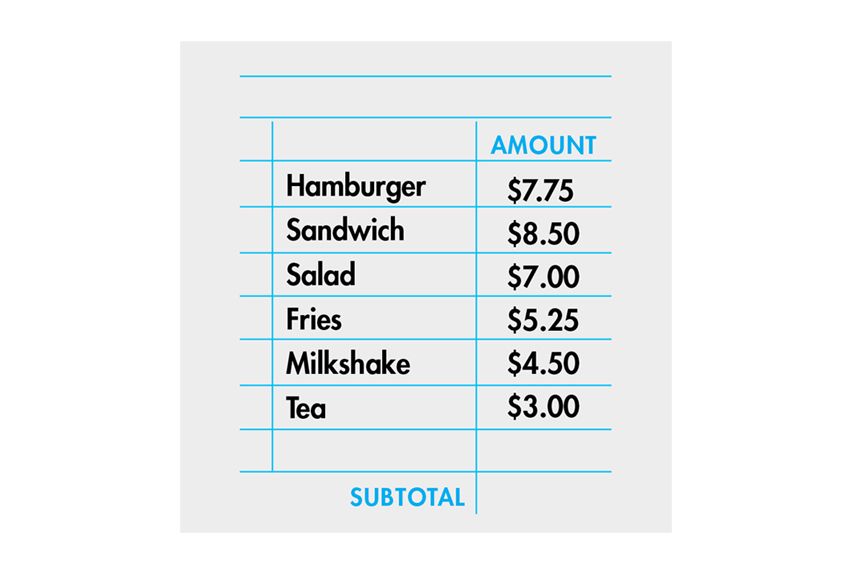

By the 12th grade, students are asked by the National Assessment to demonstrate fundamental capacities of a thinking adult, like recognizing the point of a persuasive essay. One math problem set out a scenario involving a restaurant check:

Graphic:

Test-takers were asked to add the costs of these six items and calculate a 20 percent tip. Three-quarters of the high-schoolers were unable to correctly answer one or both parts of the question.

If you, like me, are a middle-aged parent, you may remember that adults complained that education was crumbling when you were a kid too and you turned out fine anyway. You may be proud of your public school and have the magnetic car decal to prove it. You may think that, whatever the headlines say, your child is progressing well enough toward literacy and numeracy. You may be deluded.

“I don’t think parents know that their kids are behind,” says Chad Aldeman, a former Obama-administration education official who has analyzed declines in student achievement. Annual standardized-test results often arrive after the school year is over and can be hard to interpret. Teacher feedback is subjective. And a report card can offer false comfort if grading standards have gotten easier; some education-policy wonks speak of “B-flation.” While test scores can be made to mean too much, and no one likes seeing a process as magical as a child’s intellectual development reduced to a number, the hard data does tell us something we can’t otherwise know.

“There’s just been a tremendous amount of obfuscation,” says Thomas Kane, a Harvard University professor who is the co-leader of a project called the Education Recovery Scorecard. The willful ignorance starts at the top with Donald Trump, who fired the head of the Department of Education’s data division and much of its staff earlier this year, and flows down through the state governments to the district level. Kane’s project has tried to reckon the lost ground. Using a database of test results for some 35 million students in elementary and middle school, compiled with researchers at Stanford University, his group found that, on average, students are about a half a grade level behind their pre-pandemic counterparts in both math and reading. That top-line figure is troubling enough, since learning is cumulative and it’s hard for kids to catch up, but the averages mask what experts call a “fanning” effect — a widening disparity between the scores of high-performing and low-performing students.

If you look at a chart of test scores from the 1990s to the present, it arcs happily upward until the middle of the last decade as each generation incrementally learned a little more. To take but one example: In 2015, fourth-graders registered their highest reading scores ever, about a full grade level above their counterparts in 2000. Average increases like these were primarily driven by outsize gains by the lowest-scoring cohort of students as they caught up to the kids at the top. Disparities between the performance of white students and Black students narrowed. The gender gap in math disappeared, and girls were performing just as well as boys.

Then, about a decade ago, that progress began to reverse. The students scoring in the 90th percentile — the effortless and self-motivated learners — are still doing about as well on standardized tests, and in some cases better than ever, but the bottom-performing cohort is now doing far worse. “At the tenth percentile, achievement has declined by almost two grade equivalents,” Kane says. The old racial and gender gaps have once again started to grow larger. Girls are now behind boys in math by a third of a grade level. By the time those record-setting fourth-graders of 2015 graduated as the class of 2023, high-school students were registering all-time lows in reading.

Something disastrous happened here, and academics are nearly united in the opinion that the problem is not simply a product of the pandemic. The declines started before 2020 and have continued since. COVID was an accelerant, but it seems education is suffering from something deeper and more ineradicable than a disease. Adults with the best view inside the system — teachers and administrators — will tell you it starts at the beginning. Kindergartners are performing worse on assessments that measure their ability to perform simple cognitive tasks, like identifying a trait that lions and tigers share from a list. A former first-grade teacher says a substantial number of children who went through kindergarten on Zoom showed up in her classroom without the ability to visually process text, let alone read it.

In middle school, a math teacher in the affluent suburb of Bethesda, Maryland, says some of his regular students cannot calculate perfect squares in their heads; some English-language learners in his summer-school class were still doing math with their fingers. At a STEM-focused magnet high school in New Jersey, an English teacher says her students used to take 20 minutes to read short stories in class; now the task consumes nearly a whole period. Harvard has introduced a remedial algebra course to address learning gaps in its incoming first-year students — and if they can’t do math, what does that mean for the rest?

“I’ve got kids who don’t know what the word seldom means or appoint or sanctuary,” says a veteran Bay Area high-school history teacher. “The pandemic didn’t do shit. It just stripped bare for suburban parents the reality of what was happening.”

America’s atomized school system, with its emphasis on local control, assures that every district is unhappy in its own way. Mine is in Montclair, New Jersey, a town that fancies itself an island of suburban urbanity and a place that must be home to more writers, journalists, cable-news producers, podcasters, late-night talk-show hosts (okay, just one of those: Stephen Colbert), and more-a-comment-than-a-question callers to The Brian Lehrer Show per capita than any municipality in the country. It’s a place brainy people move to — lately, paying a million dollars or more for a house — because they desire to be around like-minded folks with liberal values who care about the quality of our public education, which we finance via exorbitant property taxes. We love our schools, and we repeat that mantra to ourselves even in the face of mounting evidence that we have let them languish. In this, we are far from exceptional.

I moved to Montclair in 2015, the year my son entered preschool, which was also the very moment that student achievement began to decline. (Lucky boy.) At the time, political battles were raging over the use and misuse of standardized-test scores. In retrospect, these conflicts can be seen as the death throes of a period of centrist consensus about education policy, which ran through the administrations of Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama, all of whom shared a basic belief that improving student achievement was a governmental priority and a civil-rights concern. No Child Left Behind, a signature piece of Bush legislation, created a regimen of testing and accountability measures for districts, schools, and teachers. Many left-of-center interest groups — teachers unions especially — despised the law and the education-reform movement that formed around it, especially after its most zealous adherents started to use test scores to justify divisive actions like revoking union tenure protections for teachers and directing public resources to charter schools. Progressive parents rallied around traditional public schools and their teachers and rebelled against the rote mind-set that an overemphasis on test scores created, which sucked creativity and joy out of the classroom. In 2015, it was common to see anti-testing yard signs around Montclair. Some 40 percent of its students opted out of the state exams that year.

“They were using those test scores to beat the hell out of everybody,” says Julie Borst, executive director of a progressive advocacy group called Save Our Schools NJ. It is unsurprising that scores increased, opponents of testing argue, when the policy put testing at the center of everything schools did. They say that No Child Left Behind’s goal of bringing all children to “proficiency,” a technical term for mastery of grade-level skills, was unrealistic and cite a long line of studies that have found student achievement is far more dependent on outside factors, like demographic makeup and family-income levels, than anything schools can control. “This data has been telling you the exact same thing since the 1980s,” Borst says. “ ‘It’s poverty, stupid.’ ” Schools didn’t need more incentives to teach children, the progressives argued. They needed more money.

If you wanted to test the proposition that money matters more than any other factor when it comes to student achievement, there might be no better place to do it than Montclair. Our community is wealthy and, by the standards of suburban districts, racially mixed — Black and Hispanic students and students with multiple racial backgrounds represent about 45 percent of the district’s enrollment. Since the 1970s, Montclair has operated a magnet system designed to maintain racial balance at its schools; the district currently spends around $10 million a year on bus transportation to make it work. It has historically paid its teachers better than most New Jersey districts. A few years ago, 80 percent of voters approved a referendum to spend $188 million on building upgrades, paying for necessities like replacement boilers as well as nice things like athletic fields and solar panels. All told, our district spent around $27,600 per pupil, according to Census Bureau data, which put it in the 95th percentile for school systems of its size.

“We came here thinking that this is a utopia for kids of color,” says Obie Miranda-Woodley, who is Puerto Rican and has two children in the school system. Her biracial family moved from New York in 2013 and soon discovered cracks in Montclair’s admirable façade. There were continual controversies surrounding claims of unequal treatment of white and Black children in the schools, particularly in the areas of discipline and access to advanced academic programs. But most troubling to Miranda-Woodley was what she perceived as a lack of discussion of equity in the context where it was most important: learning.

Before the pandemic, Black students had persistently lower rates of proficiency on state tests than their white classmates. The gap was around 35 points in reading and 40 points in math. Miranda-Woodley, who says her own children were at times “achievement-gap statistics,” became active in local school politics, trying to get other parents and administrators to face up to the district’s underperformance, but the community seemed to shrug off what the test scores were saying. “It’s like a buzzword: equity. ‘I care about equity as my priority,’ ’’ Miranda-Woodley says. “But the district has one or two meetings a year where they say, ‘This is the data.’ And there is no explanation about how they are going to improve it.”

For well-off white parents like me, it was easy to ignore standardized-test results entirely. Two years ago, I participated in sessions that took community input on the development of the district’s five-year strategic plan. While the final product lists “achievement for all” as its top priority and includes objectives for curriculum design and teacher training, it contains no numerical goals or any mention of how it plans to measure success. The district does not make standardized-test scores easy for parents to find, let alone act on. Individual spring testing results are posted the following fall on a web page buried inside a parent portal. An above-average score can reinforce your impression that your child is thriving until you realize all the students are declining as a group.

That is what started to happen, without much public notice, in Montclair about a decade ago. The Education Recovery Scorecard project, which charts district-level performance data, found Montclair scores fell by about a grade level in reading and half a grade level in math between 2013 and 2019. Then COVID closed the schools and exacerbated everything. Seventy percent of the district’s students scored at the lowest level on an assessment given at the beginning of the 2021 school year, indicating they needed strong support.

Amid the misery, there was hopeful news: The district had more money to spend. Congress passed pandemic stimulus bills that directed nearly $190 billion in aid to public schools, the largest education-spending intervention in history. I expected the district to use our cut of the money to address the emergency: mobilizing an army of tutors, working after school and during the summer, to compensate for the months lost to the lockdown. But the MASH unit never arrived. The Biden administration put few restrictions on how the pandemic funding could be spent. Of the nearly $8 million it received, Montclair used $2 million to buy Chromebooks for all its students and allocated similar amounts for building upgrades and professional services, including architects’ fees related to long-postponed HVAC renovations and “culturally responsive training” for teachers and administrators. It appears to have spent relatively little of the aid on instruction. “The district had the teachers keep moving forward,” Miranda-Woodley says, “without addressing how these kids fell behind.”

Michael Hartney, a research fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford, tells me that the pandemic created an unfortunate but instructive “natural experiment” to test the influence of resources on education. “This helicopter money was dumped out,” he says, “and then it was, ‘How are you going to spend it?’ ” Studies have concluded that the billions in federal aid did help close learning deficits a little, particularly in low-income school districts, which received the largest proportion of it. But its impact was disappointing relative to its size. Many district superintendents used aid to plug budget holes or went on hiring sprees, creating permanent roles with temporary funds. The number of public-school employees nationwide currently sits at an all-time high, even as enrollment has fallen along with birth rates. Most of the growth has been in ancillary roles: special-education paraprofessionals, instructional coordinators, guidance counselors, administrators. About the only staff category that is decreasing: librarians.

People who work inside the school system say the increase in staffing is a reflection not of bloat but rather the ever-expanding list of things schools are expected to deliver in addition to education. “There is only so much teachers can do,” says Sarah Mulhern Gross, a longtime high-school English instructor in another New Jersey town. “We’re not parents, we’re not therapists, we’re not doctors, but those are the roles we are taking on.” Since the pandemic, districts have been forced to contend with an explosion in the number of children reporting mental-health problems or being diagnosed with learning disabilities, which must be addressed by federal law. “Every year, I’m cutting a high-school math class and adding three for special education,” estimates Mike Citta, the superintendent in Toms River, a large South Jersey district where student test scores have fallen by about one and a half grade levels in reading and math over the past decade.

This past spring, five years after the pandemic, Montclair introduced a pilot high-intensity tutoring program for third- through sixth-graders. (It was funded by a competitive grant, not pandemic aid.) Of course, parents who could afford it had already been paying for private tutors for years. “We have spent thousands of dollars to provide educational support to our kids,” Miranda-Woodley tells me. She is hardly the only Montclair parent who bemoans inequity while grudgingly subsidizing it. (Guilty.) Martin West, a Harvard professor who has studied the fanning effect in the National Assessment data, tells me private tutoring is likely one of its drivers. According to a paper West co-authored, “Kumon In,” there are 10,000 or so for-profit tutoring centers nationwide. By contrast, there are slightly fewer CVS pharmacies.

Yet even many of our most privileged and thoroughly drilled children seem to lack some basic skills. At barbecues and in the bleachers, we middle-school parents often share anecdotal observations about what our kids don’t seem to know. How to sign their names. (They never learned cursive.) How to spell. (They do all their assignments in Google docs, which autocorrect.) How to crack open a textbook and study. That last one is a moot point because they have no textbooks to crack. Since using federal aid to buy all its students laptops, Montclair has made the devices a primary delivery mechanism. Where once kids brought home worksheets, now they toil on platforms. These software programs cost districts millions a year. A Wall Street Journal story found that one big vendor our district uses, IXL, commissioned a study and then declined to publish it once it concluded its products had little positive effect. Other research suggests that students retain more information when they read and work on paper.

As a writer, I’ve felt particularly aggrieved by the disappearance of books from my son’s backpack, and last year I went to a meeting of the Montclair board of education to ask if students could have the option of requesting hard copies in addition to PDFs. (My crusade went nowhere.) The night I attended coincided with the annual presentation of the district’s performance on state standardized tests. Administrators gave a slideshow highlighting some positive results. Montclair has rebounded from the pandemic relatively well by national standards, and it outperforms the averages for New Jersey, which is traditionally one of the best-performing states in the country. From a distance, it looked like we were doing just fine.

But if you dug into the data, you saw the fanning effect again: The largest gains came among white students and those who were classified as “not low income.” Black, Hispanic, and low-income students were still scoring far below their classmates. Their scores in math had dropped significantly since the pandemic, enlarging the achievement gap. In my son’s cohort, only 15 percent of Black students were doing math at grade level, and the entire age group had registered a ten-point drop in reading and math between the fifth and sixth grades. Just 36 percent of Black 11th-graders scored above the minimum “graduation ready” threshold on the state’s mandatory high-school exit exam in 2024. Montclair’s schools budget had increased by more than 50 percent, to nearly $200 million annually, over the prior decade, but it was still nowhere close to delivering achievement for all. That was bad enough. Then we discovered the district was broke.

Our financial debacle began with a human tragedy. Last year, the superintendent who had run the district through the pandemic, a relatively young man, died suddenly. As the school board embarked on the process of hiring a replacement, I participated in listening sessions conducted by its outside recruiters. The board eventually hired Ruth Turner, an administrator in Rochester with a background in social work and restorative justice. Initially, it seemed a curious choice. Rochester is a Rust Belt city with abysmal test scores and serious fiscal constraints, which have led to school closures. But the relevance of Turner’s experience soon became clear. In July, Turner sent out an ominous mass email announcing that in four days, she would hold a town-hall meeting about the budget. Along with a few dozen other citizens, I sat in a school auditorium and listened, dumbfounded, as she announced we were running out of cash.

It was no secret that the district had a budget problem. There were inflating costs for special education, bus transportation, and the collectively bargained benefits and salaries for teachers, which increase annually at a rate that exceeds the 2 percent cap, set by law, on the amount that the district can raise property taxes without holding a referendum. But what was once a concern was now a crisis: Turner said the district’s business administrator, who had just resigned, left behind around $12 million in unpaid bills. (Some of them, Turner later told me, were found jammed in desk drawers.) “We didn’t know what we didn’t know,” she said. By December, there would not be enough money to make payroll. Cuts were unavoidable, though Turner promised to try her best to avoid ones that impacted learning. “The classroom is sacred,” she said. “As much as possible, that will stay sacred ground.”

Our budget deficit has activated Montclair in a way its learning deficits never have. My fellow parents, confident in the capacity of their collective brainpower, have been frantically putting together spreadsheets, forming working groups, and playing amateur auditor, trying to get to the bottom of the budget mess. I have been more interested in another mystery: Why didn’t all that money we spent make a difference?

As I talked with people all over the country about the state of schools, I discovered there are a lot of communities like Montclair, other places where parents had high expectations for public education that their districts were disappointing. “The house is on fire,” a parent in Evanston, Illinois, told me. His town, a desirable and diverse Chicago suburb that is home to Northwestern University, has seen state test scores for elementary- and middle-schoolers fall by a grade level in reading and math over the past decade. A Stanford study found that its racial achievement gap is one of the largest in the country. Its enrollment has declined by almost 25 percent over six years. And it’s currently dealing with its own budget crisis, left behind by a superintendent who overspent on ambitious projects like an expensive new elementary school. (He was recently indicted on federal criminal charges related to an alleged kickback scheme.)

I heard similar reports of dysfunction from towns like Ann Arbor, Michigan, where reading and math scores have fallen by a grade level since 2018 and the school board is slashing the budget, and Newton, Massachusetts, a Boston suburb where achievement has dropped off and some parents and teachers have been rallying against “de-leveling,” a move to eliminate advanced classes on the grounds that they exacerbate inequality. The local details varied, but the common theme was that residents were being jarred out of their long-held assumptions about the excellence of their schools. “The big story is really that it’s 2025 and you and I are having this conversation,” says Tim Daly, an education expert and Substack columnist who has examined the agonies of suburban districts. “Why did it take so long for us to recognize these problems and engage with them?” Daly has described the national decline in student achievement as a “nameless depression.”

The academic researchers who are trying to explain the underlying causes of that depression say its timing is their best clue. Test scores started to fall when the children born during the first year of the iPad, 2010, started to enter the school system, and, to some, that points to a simple explanation: It’s the screens. As intuitive as that answer may seem, it cannot account for why girls have again fallen so far behind boys in math, for instance. The use of devices is universal, and educational regression is unevenly distributed. “I think screens are an excuse right now,” says Carol Jago.

To policy players of the education-reform movement, the timing suggests a vindicating explanation: Regression began after they started to lose political battles over the value of testing. Chris Cerf, a Democrat who served as a top New York City schools official under Mayor Michael Bloomberg and as New Jersey’s state education commissioner for Republican governor Chris Christie, says, “The old reform hawks, like me, blame this on a radical abandonment of a playbook that was showing real progress.” He points out that even as test scores plummet, grades are inflating and graduation rates continue to rise. “It’s in everyone’s interest, except of course the children’s, to essentially turn a blind eye to the achievement trends.”

You might call this the Declining Standards Hypothesis. In its telling of history, the significant event in the past decade came in 2015 with the passage of a federal law signed by Obama that rolled back No Child Left Behind and left it to states to decide how to enforce accountability. “There was an idea that we were in a transition to something better,” Daly says. “It turned out to be a transition to something much worse.” Many states, particularly Democratic ones with strong unions, began to back away from using tests to guide policy decisions. Then during the pandemic, standardized testing was mostly suspended. When students came back, it seemed unfair to judge them — and by extension, their schools — too harshly for their inadequacies.

Advocates of the Declining Standards Hypothesis can point to many indicators of softening expectations. New York, Massachusetts, and Oregon have abolished, suspended, or announced an intention to phase out graduation exams that require high-schoolers to demonstrate proficiency in core subjects. Other states, including New Jersey, have lowered “cut scores,” making it easier to show proficiency by defining it down. Programs for gifted students, another continual flash point, have been scaled back in many places. Critics of these programs say they have long reinforced in-school segregation, offering students unequal opportunities. But instead of providing everyone who wants access to accelerated classes the support required to succeed, some districts have found it easier to do away with them entirely, resulting in what Shlomit Azgad-Tromer, a Brookline, Massachusetts, mother who started a group to defend advanced classes in her district, calls “mediocrity as policy.” Formally and informally, many districts have made grading more forgiving, for example, by putting in a floor on scores to make it easier for students to pull up an F. Superintendents get to hand out more diplomas and reap the applause and career benefits. But graduation rates are often not what they seem. An Asbury Park Press investigation earlier this year found students in that low-income shore town, where graduations had soared, were earning credit for tasks like babysitting and doing laundry.

The rationale linking all these policies is that supposedly uniform standards are applied unevenly against those who are already disadvantaged, often with devastating life consequences. Still, it is not hard to understand why even some Democratic officeholders in San Francisco erupted in ridicule when its school board recently proposed a “grading for equity” plan that made a score as low as 41 percent a C. Failure is harsh, but sending teenagers into the world without a basic education is neither popular nor progressive. “In lots of weird ways, the political left has used equity to diminish high expectations for kids,” says Aldeman, the former Obama-administration official.

The centrist education reformers like to highlight the counterintuitive success of a handful of outliers: Some southern states, once laggards in public education, have been making huge strides in student achievement, even as northeastern states have fallen back in the pack. Economically disadvantaged fourth-graders in Mississippi and Louisiana have been scoring better on the National Assessment than their counterparts in New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts. Since 2013, Mississippi’s scores for fourth-graders have gone from the bottom of the state rankings on the National Assessment to ninth in reading and 16th in math.

Academic researchers have only just begun to examine the “southern surge.” Some credit concerted teacher training, coaching efforts, and a back-to-basics philosophy that makes use of old-fashioned teaching tools, like math flash cards. Some point to the “science of reading,” a phonics-based curriculum that Mississippi was early to embrace and that is now being implemented all over the country (including in New York City, which just announced a jump in reading test scores). Another thing that the conservative southern states tend to share is a continued commitment to test-based accountability measures, which their teachers have had to swallow because they have weaker unions. In Mississippi, children are also held accountable. Third-graders who fail to show reading proficiency are held back by law, which may help to explain why its fourth-graders test so well.

A year ago, the superintendent of education who led Mississippi through the period when it began to climb the rankings, Carey Wright, was hired to run the schools in Maryland. Over the prior decade, despite increasing its education spending by 37 percent, Maryland saw its reading scores for fourth-graders drop by around 20 points on the National Assessment, according to data compiled by the Georgetown Edunomics Lab. Wright proposed implementing the same third-grade retention policy that Mississippi uses, but she ran into opposition. Parents bombarded her department with hostile emails. Politicians voiced nervous objections, questioning the policy’s impact on the neediest students. Wright had to retreat. “The context was different here,” she says.

As America has split into cells — communities of the like-minded — the politics of education has likewise divided into polarized realities. There are education researchers on the left who insist that the “Mississippi miracle,” as it has been called, must be an illusion or the product of test-score trickery. (One data point the skeptics cite: If you look at Mississippi’s eighth-graders, their performance falls back to earth.) At an October debate, New Jersey’s next governor, Mikie Sherrill — a Montclair parent — attacked her Republican opponent for “citing places like Louisiana and Mississippi, I think, some of the worst schools in the entire nation.” She said, “If that’s where he wants to drive us to, I think voters should be aware.” In many liberal communities, talking of test scores — or even using the word achievement — has come to sound right-coded.

“I think it’s ironic,” Kane says of his post-pandemic recovery findings, “that the very places that purport to care the most about equity have done the worst job in terms of catch-up.” Complacency about education is a luxury that parents can purchase by buying a home in the right Zip Code. And yet it’s still natural to wonder whether you have read them the right books, taken the right approach to screen time, asked the right questions at the teacher conference, even settled down in the right place. Earlier this year, posters began to appear on New Jersey commuter trains that seemed designed to stoke these anxieties. MARCUS WILL NEVER BE AN ARCHITECT, read one, which was illustrated with a photo of a sweetly smiling child carrying a backpack. The advertisements cited scary statistics — 55% OF NEW JERSEY’S FOURTH GRADERS CAN’T DO MATH AT GRADE LEVEL — and included a QR code that led to a website for a nonprofit organization called Wake Up Call New Jersey. Its objectives were mysterious.

The group turned out to be the personal project of Laura Overdeck, an education philanthropist who is married to a hedge-fund manager worth an estimated $8 billion. (They are currently going through a well-publicized divorce.) A decade ago, Overdeck started a nonprofit to promote childhood math skills, which she says led to a realization that parents need to be alerted to achievement declines. This school year, her new advocacy group chose to paper two particular New Jersey school districts, one of which was mine, with glossy flyers. ATTENTION PARENTS: MONTCLAIR STUDENTS ARE FALLING BEHIND, one read on the front. On the back, it cited our standardized-test results: 38% OF MONTCLAIR FOURTH GRADERS ARE BEHIND GRADE LEVEL IN MATH. One day, an electronic-billboard truck with the same message parked outside my son’s middle school as it let out. The concerted blitz extended even to YouTube ads that were seen by kids.

When I spoke to Overdeck in October, she told me she meant to provoke a reaction. “There’s been a lot of effort to get parents to not like tests and to be mistrustful of them,” she says. “Society has got to take the red pill on this.” She hopes parents will be inspired to look closely at their own children’s test scores and initiate “difficult conversations” with their teachers about them — and, from there, agitate for broader change in their districts.

Understandably, the targets of Overdeck’s blitz were defensive, suspicious, and angry that their kids were being confronted with marketing material that implied they might be dumb. On Facebook and WhatsApp, Montclair parents massed like white blood cells to attack the invasive agent. They questioned Overdeck’s motives: Was she pushing vouchers or charter schools? Fighting the Republican culture war? Trying to defeat Sherrill? Overdeck, a Republican, had donated $500,000 to a PAC supporting Republican candidate Jack Ciattarelli. (She says her group is nonpartisan and has no position on vouchers or charter schools.) A middle-school teacher, the father of a local Democratic officeholder, appeared at a school-board meeting and waved a flyer to decry the interference of “a well-funded right-wing organization.” If Overdeck’s intention was, as she claimed, to start a local conversation — or even a movement — she had accomplished the opposite, poisoning the discourse. It hardly mattered that her numbers were correct.

A cynic might say this shows that Democrats believe in data only until it elucidates their shortcomings. But an inability to face the facts is bipartisan. And Republicans’ preferred solution to this crisis of public education is its abandonment. Beyond Trump’s slashing of federal education, including programs aimed at improving low-income-student achievement, numerous conservative states have instituted “school choice” programs that redirect public funds to private schools. Vladimir Kogan, an Ohio State professor who studies the politics of education, says many Republicans turned against standardized testing when studies began to cast doubt on the effectiveness of vouchers. “Amongst conservatives, there is skepticism,” he says, “because some of their favorite programs don’t lead to better test scores.”

Kogan recently published a book, No Adult Left Behind, which seeks to locate the source of all this systemic failure. He told me he was inspired by his experience as a parent of two adopted children of color in Columbus, Ohio, during the pandemic. As he watched his city’s school board bicker over reopening plans and other issues, he started working on his book, which delves into the way public education is governed on the local level. In most places, districts are overseen by elected boards that are supposed to represent the best interests of the system’s beneficiaries: the students. But it often does not work that way in practice. In his research, Kogan analyzed the results of more than 50,000 school-board races in 16 states and found, in general, they are characterized by low turnout and dominated by “mostly childless, overwhelmingly white upper-income voters.” This creates what Kogan calls a “democratic deficit,” in which those with the most at stake have less influence. “Adult political considerations and adult political objectives ultimately drive policy,” he says. “It’s not that people don’t care about kids, but those considerations are of secondary importance.”

Kogan’s book argues that the kids get the system the grown-ups deserve. We adults express ourselves through our arguments and our votes, by posting on social media and staking signs in our front yards, but our systems signal what we really value in another language: money. Maybe this is one reason people in Montclair were so comfortable in their assumptions about their schools. They couldn’t be so bad if we spent so much on them, could they? It wasn’t until the new superintendent arrived and exposed the district’s mismanagement that we began to wonder if the money had been going to the wrong places. Turner told the school board she had never worked in a district that invested less in curriculum and instruction. Even as Montclair’s budget has spiraled out of control, the amount it devoted per pupil to core educational expenses actually declined over the three most recent years.

Since the superintendent first informed us of our unpaid debts, the news about our district’s finances has grown only more bleak: Further investigation determined that it was on pace for a $7 million shortfall this school year, bringing the amount the district has to find to around $20 million, or more than 10 percent of its total budget. By the time Back to School Night rolled around, the chatter on Facebook and WhatsApp was all indicators of budgetary stress. Field trips were called off. The schools were out of copy paper. (It turned out the district had not paid a large bill to Staples.) The musical at Buzz Aldrin Middle School, where my son goes, was likely to be canceled because there was no money to pay for after-school clubs. (The PTA launched a drive to raise the necessary $12,000.) Turner held another town-hall meeting in late September where she outlined a plan that involved taking an emergency loan from the state to pay off our debt and then holding a special election in December to ask voters to approve taxes to cover the sum required to pay back the loan and close the deficit. If the vote fails, the district will end up under the management of a state monitor who can unilaterally slash staff and programs. “Everything is on the table,” Turner said. My son had come along, a civic interest I attribute to his fascination with adult misbehavior. He and a friend sat in the back row, absorbing the bad news.

Speaker after speaker demanded a forensic audit to probe for corruption, but Turner offered a more banal explanation: We had been living beyond our means. It appeared that under her deceased predecessor, the district had begun to conceal a growing structural deficit by kicking unpaid bills from one year to the next. Now, someone was going to have to pay — either the taxpayers or the kids.

“If we can’t afford it, we can’t have it,” Turner told me in late October. She said she knew asking voters to raise their own taxes was an iffy proposition, and so she was preparing a plan B in case the town voted “no.” “It certainly will be something that Montclair has never experienced,” she said. A few days before, the district had sent advance notice to more than 100 staff members who would lose their jobs. There would be cuts to language and restorative-justice programs, extracurricular activities, and athletics. Positions that provide extra instruction for struggling students during the school day would be eliminated. She said she would have to consider extreme measures, like closing schools. Under a state monitor, even our treasured magnet system could be vulnerable because it is dependent on expensive busing, which might be scaled back.

If the referendum wins, Turner said, a realistic approach to budgeting would still mean “right-sizing” staff levels and class offerings. “We’re going to have to struggle through this painful process, because we might have to let go of things that we’ve had for a very long time,” she told me. “But it’s not necessarily a bad thing. It might be for something better.” In the interim, children, like my son, who suffered through remote learning in their elementary years will now face austerity in high school. That is, if they go there: Private-school open houses are packed.

I thought about all the little issues Montclair had been agonizing over these past few years. There were protests about cutting down a few old-growth trees to make way for our new artificial-turf baseball field. There was a campaign for equity for the high-school robotics team, which is now funded like an athletics program. There was an argument over whether to retain an inclusive calendar that adjourns for holidays including Diwali and Lunar New Year, interrupting instruction and pushing the school year late into June. Meanwhile, we had lost track of the big thing.

In November, at the end of yet another exhausting school-board meeting, district administrators presented the results of the spring’s tests. There were some modest signs of improvement from the year before, but not many. “I’m almost speechless,” said one board member. Less than half of all Algebra 1 students scored at or above grade level, and just 14 percent of Black students did — a figure another board member called “the most distressing number” in “a sea of distressing numbers.” Pressed for an explanation, the new superintendent was direct. “Our budget reflects our priorities,” Turner said. “I don’t know how much of a priority teaching and learning has honestly been.” We had asked our schools to do so much. And we ended up with so much less than we expected.

More From the Stupid Issue

Quiz: Are You Smarter Than an Eighth-Grader From 1899?A Theory of Dumb

From Intelligencer - Daily News, Politics, Business, and Tech via this RSS feed