Today’s games have forgotten the lessons of history, according to veteran RPG developer and Fallout co-creator Tim Cain. In a YouTube video uploaded this week in response to a viewer who asked whether old games could offer any “lost wisdom” for today’s game developers and designers, Cain responded with an emphatic “Yes.”

Today’s games, Cain said, suffer from an identity crisis: “They don’t really know what they want to be,” he explained. “They try to be everything to everyone: designed by committee, making a publisher happy, trying to guess what the largest demographic wants.” Old games, he said, had a stronger focus—because they had no other choice.

When Cain says old games, he means old games. We’re not talking about his work on the first Fallout here, which is already more than a quarter of a century old. Instead, Cain said we should hearken back to games from the '80s, when he started working in the games industry as a teen.

Computer hardware in the '80s was, obviously, less capable. And crucially, Cain said, there were no shared hardware and software standards, even as “games were being made for PC, for Apple, for Atari, for Commodore, for a wild assortment of consoles.”

Game developers, meanwhile, were less specialized. Programmers were also artists and sound designers, working without documentation to figure out how to get games to run within the hardware constraints of the era.

“These games were really focused, because they had to be,” Cain said.

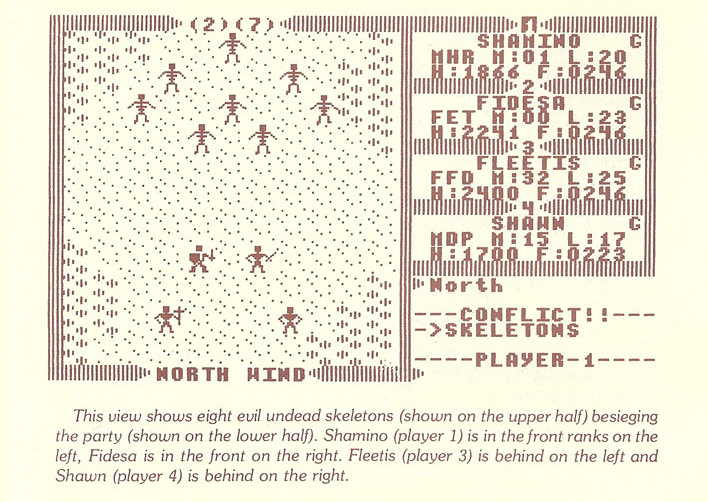

An image from the manual of Ultima 3, a game which is old. (Image credit: Origin Systems)

The first lesson the games of today can learn from their early forebears, Cain said, is efficiency. The limited memory and processor capabilities of the '80s left programmers with such tight margins that they had to time the display of individual pixels down to the millisecond, or creatively juggle the values stored at specific memory locations.

“It’s not that you want to be efficient, or ‘wouldn’t it be cool if we were efficient,’” Cain said. “It was ‘you write efficient code or your game doesn’t work on the Atari console.’”

That efficiency, by necessity, was equally present in the era’s gameplay design. Games today have accreted layers of peripheral activities and systems: An action game might have crafting, and puzzles, and companion progression mechanics all pushing and pulling on each other. Designers in the '80s had to be more deliberate.

Wizardry, an old videogame. (Image credit: Sir-Tech)

“You couldn’t do all that,” Cain said. “You had to pick: What segment of all that gameplay do I want to represent? And then you did that. The idea that you could have a core game loop that was a huge variety of actions just did not exist.”

Because they could only be so broad, '80s games naturally emphasized the impact and execution of their narrower focus: If the entirety of Gauntlet is entering a dungeon to fight things for treasure, it had better nail fighting things for their treasure.

As a result, Cain says, '80s games avoided the danger of “becoming indulgent” like modern games have. “They add too many things, thinking more of those things make the game better,” Cain said, “when really what they do is dilute the game.”

As he often does, Cain illustrated his point with food, comparing '80s game development to a high-end restaurant where a skilled chef can cook delicious food using just a few ingredients of the best quality. The implication is that today’s big budget games are something more like a buffet, where the variety of flavors has a higher priority—even if the quality suffers.

“The difficulty is when you start making a game, it’s easy to go ‘I want to add this, and I like this, and I just played a game that had this so I want to pull it in,’” Cain said, noting that indie games with small teams often benefit from a tighter scope than bigger game productions.

“You need to be simple. You need to stay focused and whatever you do has to be extremely well executed. And then you’ll be like that fancy restaurant. You don’t got a lot of ingredients in that meal, but that meal was delicious.”

2025 games: This year’s upcoming releasesBest PC games: Our all-time favoritesFree PC games: Freebie festBest FPS games: Finest gunplayBest RPGs: Grand adventuresBest co-op games: Better together

From PCGamer latest via this RSS feed

Yes, yes, and more yes.

Video games are the perfect platform to get weird and specific because the player doesn’t have to be the mass market. It just has to be something that market hasn’t seen before.

One of my favorite games of all time is Okami and there’s almost nothing like it on the market before or since. That game isn’t good because it appeals to everyone. It’s good because it does things no other game does.

For every dozen generic military shooter released, there’s a hidden gem waiting for you specifically. The big games are popular, but once you’d played a few, you’ve played them all.