This story was co-published with The Trace, a nonprofit newsroom covering gun violence in America.

In September, the US Department of Justice sued the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, alleging that it had deprived “thousands of law-abiding” Californians of their fundamental rights. The lawsuit—spearheaded by the DOJ’s storied Civil Rights Division—was unusual. It didn’t take aim at the notorious “deputy gangs” that have operated inside the sheriff’s department for decades. Nor did it target the department’s former leadership for allegedly stonewalling outside investigations of deputies suspected of abusing detainees. Instead, the DOJ accused LA County’s top cop of slow-walking concealed carry permits in a “systematic obstruction” of Second Amendment rights.

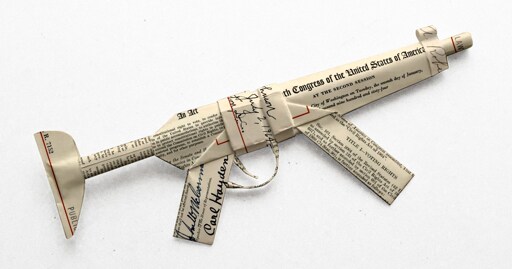

Under Trump and Dhillon, the Civil Rights Division has morphed into a potent weapon in MAGA’s nonstop culture battles.

The case—which the Trump administration touted as the DOJ’s first-ever “affirmative lawsuit in support of gun owners”—relies on a decades-old statute intended to help the feds crack down on local law enforcement agencies engaged in a “pattern or practice” of civil rights violations. It’s the latest sign that under President Donald Trump, the Civil Rights Division has made a hard break with its onetime commitment to protecting the politically disempowered and has morphed into a potent weapon in MAGA’s nonstop culture battles.

“First-of-its-kind lawsuit dropped—the Second Amendment rights of Californians will NOT be trampled,” Harmeet Dhillon, a Republican activist and lawyer Trump picked to lead the Civil Rights Division, posted on X after filing the suit.

First-of-its-kind lawsuit dropped—the Second Amendment rights of Californians will NOT be trampled. This @CivilRights Division will fight LA’s deliberate delays on concealed carry permits, defending your 2A rights!

https://t.co/Egh11Rivn5 pic.twitter.com/ArJXqCfNKL

— AAGHarmeetDhillon (@AAGDhillon) September 30, 2025

Seven months into Dhillon’s tenure, the Civil Rights Division is unrecognizable. Founded in 1957, it focused initially on ensuring that Black Americans in the South had access to the ballot. Its mandate grew with the 1964 Civil Rights Act and other legislation barring discrimination based on traits such as race, religion, sex, and national origin. Congress enacted the “pattern or practice” law in 1994, three years after the videotaped police beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles. The provision quickly became the DOJ’s chief tool for bringing oversight when officers engage in rampant, unchecked misconduct against marginalized groups.

Under the Obama administration, the DOJ used the law to force a settlement with the same LA Sheriff’s Department after finding in 2013 that officers had subjected Black and Latino people to brutal violence, illegal searches, and other forms of discrimination. Until this year, the law had never been invoked on behalf of gun owners, whose right to possess firearms for self-defense the Supreme Court recognized only in 2008.

In interviews, Civil Rights Division veterans who left during the current or previous administrations said various Trump executive orders—which often seek to undermine existing civil rights policies—are guiding enforcement. Christy Lopez, a professor at Georgetown Law who served in the division and led the Obama-era investigation of the LA sheriff, said, “It’s clear that they are co-opting the division to serve an agenda that is in some ways antithetical to civil rights.”

Dhillon has an appetite for provocation and dispute. In 1988, as the editor of Dartmouth College’s right-wing student paper, she cited the school’s “liberal fascism” in defense of her decision to publish a satirical opinion piece by another student that likened the college president to Adolf Hitler and campus conservatives to Holocaust victims.

She earned a law degree in 1993 from the University of Virginia, where she was president of the school’s Federalist Society. This year, Dhillon and a DOJ deputy who is also a UVA alum went after diversity efforts at the school, intensifying a broader conservative pressure campaign to get rid of university President James Ryan, who resigned in June.

“Gun owners are not in any way an oppressed minority.”

Dhillon’s advocacy work hasn’t always been on behalf of right-wing interests. After the September 11 terrorist attacks, Dhillon, a practicing Sikh who immigrated from India to London to the United States as a child, helped lead efforts to protect her community from growing harassment. “While my brother, a turbaned Sikh lawyer, was being called ‘Osama’ at Candlestick Park and Sikh taxi drivers were being assaulted, we made it a priority to keep Sikhs and other Americans safe from this irrational and discriminatory violence,” she told the Senate Judiciary Committee in a written questionnaire this year. “I spent hundreds of hours drafting legal memoranda and advocacy materials for publications, training for law enforcement, and more.” Her efforts drew the notice of the ACLU of Northern California, which appointed her to a two-year stint on its board.

In the Trump era, Dhillon has become a MAGA world star. She co-chaired Lawyers for Trump in 2020, spread doubts about that year’s election results, and called on the Supreme Court to intervene on Trump’s behalf. Her private San Francisco-based firm collected $10 million from Trump’s political operation in the 2024 cycle, and it has fought against gender transition for minors, alleged anti-white bias, and the perceived stifling of conservative speech.

Dhillon has drawn occasional heat from some extreme elements on the right. Her faith became an issue in a failed 2023 bid to chair the Republican National Committee. She told Politico at the time that it had been hurtful to discover that “a handful of RNC members” had “chosen to question my fitness to run the RNC by using my devout Sikh faith as a weapon against me.” Dhillon delivered a Sikh prayer at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee in 2024, prompting a particularly venomous response from some commentators.

But Dhillon retained Trump’s loyalty. She’s become a key figure in implementing the president’s legal agenda and has worked overtime to mollify powerful firearms groups that, at times, have criticized the Trump DOJ for being insufficiently aggressive in opposing gun control laws.

Satisfying the gun rights crowd is work that Dhillon—whose former private firm dabbles in Second Amendment law—touts publicly. Neither she nor the DOJ responded to written questions for this story. But in a recent issue of the Dartmouth alumni magazine, Dhillon suggested that the division’s gun rights work is just getting underway, telling an interviewer that “we’re forming a Second Amendment section of the Civil Rights Division. That’s never been done before.”

The concealed carry lawsuit against the LA Sheriff’s Department, which is the division’s highest-profile move on behalf of gun interests, isn’t frivolous. The county’s permit program has indeed been plagued by delays, and last year, in a lawsuit brought by gun rights groups, a federal judge found that the agency had likely violated the plaintiffs’ Second Amendment rights.

Yet the existence of a well-resourced private lawsuit highlights another way in which the Civil Rights Division’s intervention marks a departure from past practice. Historically, it has stepped in to uphold the rights of those with limited political clout and access to levers of power. “Proponents of Second Amendment rights have an abundance of political power that has allowed them to not only protect, but dramatically extend their rights,” said Lopez, the former DOJ official now at Georgetown. “Just because they don’t always get what they want, or because there are some process issues in getting them what they want, doesn’t mean they are a politically marginalized group.”

“It was extremely shocking to see the press release.”

Before bringing a pattern or practice suit, the DOJ typically issues a report that sums up evidence the government has collected. These reports alert the public to substantiated misconduct and can be a basis for settlements. When the DOJ settled with the LA sheriff in 2015, reforms were tailored to the findings that the DOJ had made public two years before. The DOJ released no such report before filing its concealed carry suit in September. In March, when the agency first announced its investigation of the permit delays, lawyers who specialized in law enforcement oversight were caught unaware, said several division attorneys who left this year. “It was extremely shocking to see the press release,” said one, who spoke anonymously to share internal details of the episode. “It was just such a sharp departure from the norm.”

Lopez has written critically of the division across administrations, arguing that it has too often favored symbolic gestures over aggressive enforcement and that it has been overly attuned to political considerations. Though imperfect, she said the division has done vital work. While allowing that a scenario like the permit delays in LA may lead to constitutional rights violations, she said the suit is a dubious use of limited resources. Lopez fears that such moves could undermine the legitimacy of the division and the broader federal government.

“I am worried that once this administration is gone, the ability of the division to enforce civil rights protections will be forever compromised,” Lopez said. “And it will be viewed as what it is now, this cynical, entirely political division, which is actually pushing an anti-equity agenda.”

Career staff and leadership have been forced out under Dhillon. Figures the DOJ gave Congress and a list of departures released in October by Justice Connection, a network of agency alumni, suggest that nearly 400 people, including 75 percent of attorneys, have left the division since January. When Dhillon gave an interview to her former client Tucker Carlson in May, she described the reaction of career DOJ attorneys to her arrival. “They had crying sessions, struggle sessions,” she said. “There was open crying in the halls.”

A recently departed DOJ lawyer, who spoke anonymously to provide details on the current situation, said: “It’s almost impossible to quantify losing three-quarters of the expertise of the Civil Rights Division. The people who are left, God bless them, are treading water and cannot pursue the work that is necessary to defend the constitutional rights of every American.”

The division’s focus, the lawyer noted, has shifted dramatically. Under Trump and Dhillon, “it has targeted universities that allowed peaceful student protests, rather than standing up to landlords extorting sex from vulnerable women, police departments engaged in widespread use of excessive force, and the jailing of people who are unable to pay petty fines.”

Before Trump was reelected, there were more than 30 attorneys in the unit enforcing the pattern or practice law, the lawyer said. There are now three, they said. In the private suit brought by gun groups against the LA sheriff—in which the parties reached a tentative settlement October 31—six attorneys represented the plaintiffs.

Lawyers newly tapped to serve in Dhillon’s division include an attorney who represented January 6 rioters and likened them to victims of the Nazis and a GOP activist from Florida who called Covid-19 vaccines “the mark of the beast.” There have been wholesale mission reversals. Citing concerns over “election integrity,” the division has sued to obtain voter information in blue states and dispatched staff to six heavily Latino counties in California and New Jersey to “ensure transparency, ballot security, and compliance with federal law.” Last week, the division joined a suit filed by the California GOP, alleging that congressional maps recently approved by state voters—an effort by Democrats to counteract recent Republican-led gerrymandering in Texas and elsewhere—are themselves illegal. Dhillon’s former law firm is representing the state GOP in the case, and Dhillon is recused from the case.

Entire areas of work, like oversight of police departments and prisons, have been largely shelved and the division’s work wholly subordinated, in Dhillon’s words, “to the priorities of the president.” Among those priorities, Dhillon’s focus on Second Amendment rights stands out as entirely new terrain for the division. In part, the modern gun rights movement arose in the 1970s amid a broader conservative reaction to the upheaval and shifting societal norms of the 1960s, which the Civil Rights Division reflected. In the decades since, gun advocates have adopted the resonant language and narratives of the civil rights struggle and deployed them on behalf of gun owners, who are predominantly white and male.

Timothy Zick, a professor at William & Mary Law School who has studied the rhetoric of the gun debate, said arguments that gun owners are misunderstood victims of discrimination and judicial bias are, like most underdog stories, potent. However, he said there are good reasons to doubt that the Second Amendment has been relegated to “second class” status, as advocates maintain. Most states now allow gun owners to carry in public without a permit and constrain local firearms restrictions. Many states have passed anti-discrimination laws to protect gun rights, and multiple jurisdictions nationwide have refused to enforce gun laws, declaring themselves Second Amendment sanctuaries.

“Gun owners are not in any way an oppressed minority,” Zick said. “If anything, the Supreme Court and lower courts are treating the Second Amendment as a super-right. It has privileged status.”

In a federal financial disclosure completed before being confirmed as head of the Civil Rights Division, Dhillon said she planned to sell her private firm to her brother. Since her departure, Dhillon Law Group has continued to bring suits against federal agencies, including one filed in May against the DOJ seeking agency records related to former President Joe Biden’s “mental fitness.”

At the Dhillon firm, gun rights litigation has been a modest part of the practice. Firm attorneys have sued over pandemic restrictions that stifled a gun rights rally on the grounds of California’s State Capitol building, a state data breach that exposed confidential personal details of gun permit holders, and San Jose’s requirement that gun owners carry liability insurance.

The firm’s highest-profile gun rights work has been representing Rare Breed Triggers in cases involving the DOJ. Rare Breed makes forced reset triggers, which allow certain semiautomatic rifles to fire more rapidly. The company’s founder is also behind an apparel company called Pipe Hitters Union—“pipe hitter” is slang for special operations military personnel—and another that sells Spartan- and Christian Crusader-themed AR-15 components.

In a complaint that Merrick Garland’s DOJ brought against Rare Breed in 2023, the government alleged that company principals were brazen in their defiance of the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, continuing to sell forced reset triggers after being told it was illegal to do so. Rare Breed objected to the basis of the suit, arguing that the government’s classification of its product as an illegal machine gun was bogus.

In August 2021, the complaint states, the ATF received a call from a number associated with the law office of one of Rare Breed’s owners. The caller said that the government was engaging in “treasonous” behavior and that they planned to assemble and protest at an ATF office. “We are bringing the rocket launcher,” the caller said. The Rare Breed owner denied any involvement in the threatening call, and a federal judge ultimately found that the government had failed to prove otherwise.

Representing Rare Breed for Dhillon Law Group in those cases was David Warrington, a founder of the National Association for Gun Rights, which was involved in related DOJ litigation. Gary Lawkowski, another attorney at the firm, represented the gun rights association. Trump named Warrington, who had worked on his campaign, as White House counsel on December 4, 2024, and Lawkowski joined him as a deputy. Trump nominated Dhillon five days later.

On May 16, the DOJ announced a settlement with Rare Breed that allows the company to sell its triggers. The settlement requires Rare Breed to refrain from selling similar devices for handguns and “to take all reasonable efforts” to enforce its patent by seeking court injunctions against copycat manufacturers. Public safety is the stated rationale for these requirements, but some in the gun world have questioned the deal, suggesting that the DOJ awarded Rare Breed a market monopoly for a product the government had previously asserted was illegal.

Patent law experts I contacted were perplexed. “It’s just strange,” said David Schwartz, who teaches intellectual property at Northwestern University’s law school. “I’ve never seen an agreement to enforce a patent as part of a settlement with the government—and this is not even a patent case.” Schwartz said the agreement could help Rare Breed defend its turf. After finding that a patent has been infringed, courts balance several factors, including the public interest, when deciding whether an injunction is warranted, he said, and the settlement could bolster Rare Breed’s arguments.

Charles Duan, a law professor at American University, said by email that the settlement confers a clear edge. “Rare Breed’s device is now effectively safe-harbored from regulation, whereas other producers would still be at risk, giving the company a huge market advantage given the patent,” Duan wrote. “The question in my mind is: Are other companies going to lobby the DOJ now to favor their patents similarly?”

Warrington withdrew from the case days before Trump’s inauguration. According to a White House official who provided information on background, neither Warrington nor Lawkowski were involved in the settlement. There is no indication that Dhillon played any role in the case. Rare Breed officials and current Dhillon Law Group attorneys who represented the company did not respond to requests for comment.

Questioned on the settlement in a June interview posted to YouTube, Rare Breed’s president, Lawrence DeMonico, dismissed the notion that the DOJ had awarded a monopoly, saying Rare Breed had always intended to enforce its IP rights, settlement or not. “We already have a government-sanctioned monopoly,” he said. “It’s called a patent.”

In addition to filing suit against the LA sheriff, Dhillon, in her DOJ role, has filed several briefs in support of gun rights groups seeking to strike down firearms restrictions. On September 22, a federal appeals court heard arguments in a challenge to an Illinois law that restricts the sale of assault weapons and high-capacity magazines. The DOJ intervened, and Dhillon personally appeared in court to argue against the legislation.

“The United States has a strong interest in ensuring that the Second Amendment is not relegated to a second-class right,” she told the court, “and that all of the law-abiding citizens of this circuit remain able to enjoy the full exercise of their Second Amendment rights.” Dhillon chronicled her involvement on X, posting about her consuming preparation and noting that she was unwinding by making a needlepoint image of an eagle.

“The United States has a strong interest in ensuring that the Second Amendment is not relegated to a second-class right.”

In May, she filed a brief with the Supreme Court on behalf of challengers to a Hawaii law that restricts the carrying of guns on private property; the court will hear the case in January. Then in September, Dhillon filed a brief with the 3rd US Circuit Court of Appeals backing a challenge to New Jersey’s assault weapon and large-capacity magazine bans.

Until now, every appeals court to consider an assault weapon or high-capacity magazine challenge has upheld those laws, but judges in the Illinois and New Jersey cases have yet to rule. If the plaintiffs in either case prevail, it will increase the already-high likelihood that the Supreme Court will soon consider such bans, which could result in the prohibitions—one or both of which are in place in 14 Democratic-leaning states and the District of Columbia—being declared unconstitutional.

Still, gun rights groups have not been happy with all of the Trump DOJ’s moves on guns. In January, for instance, the 5th Circuit struck down a federal law that prohibits firearms dealers from selling handguns to those under 21. But the DOJ convinced a lower court to issue a narrow ruling applying only to the individual plaintiffs and members of the gun rights group behind the suit. The DOJ also urged the Supreme Court not to consider a separate challenge to the same law.

Andrew Willinger, executive director of the Duke Center for Firearms Law, said those moves are consistent with a broader pattern: Trump’s DOJ has been eager to challenge firearms restrictions in blue states, but quick to protect federal gun laws, particularly those that allow the government to prohibit certain classes of people—drug users and felons, for example—from owning guns.

“It seems as if they don’t want courts telling them whether these prohibitions are constitutional,” Willinger said of the DOJ, which is establishing a program that will allow some felons to have their gun rights restored. “They want to decide, as an executive branch matter, who is sufficiently reformed to get their guns back.”

Willinger said there’s an element of performance to the DOJ’s involvement in these cases—the agency clearly wants to be seen as crusading for gun rights. And he expects the DOJ to ally with gun rights groups in cases in which “it can most successfully characterize state or government actions as motivated by anti-gun animus.”

Among the Second Amendment groups expressing dissatisfaction with the DOJ has been the National Association for Gun Rights, the Dhillon Law Group client founded by Warrington, who now serves as White House counsel. On October 10, citing DOJ legal moves aimed at preserving federal gun laws, the group accused Attorney General Pam Bondi of having “failed the Second Amendment” and called for her firing, leading Dhillon to defend her boss.

“Please trust and believe that this is the most Second Amendment friendly Department of Justice in history,” Dhillon said in a video posted to X. “Yes, that’s a low bar, yet we’ve managed to rise way above it.”

From Mother Jones via this RSS feed