Last night, Russia attacked Ukrainian civilians with more than five hundred drones, cruise missiles, and rockets. Most were shot down, but one rocket got through to Ternopil in western Ukraine, struck an apartment building, and killed at least twenty-five civilians, including three children. Across the country apartment buildings, shops, post offices, and power plants were in flames. This is is latest enormous war crime in Russia’s criminal war.

Meanwhile, we learn that Putin and Trump (or their emissaries) have been secretly consulting about a settlement to the war that Russia likes. Given the inherent traps of allowing an aggressor to decide the outcome of his war, I will try to take a step back and give a quick historically-informed sense of how negotiations might actually work. Here are ten basic principles.

In effective negotiations, concessions are not made in advance. No one yet knows what we are conceding (in the name of Ukrainians) in the present proposal, but in the past the Trump administration has floated enormous concessions: that Ukraine should not join NATO; that Russians should not be tried for war crimes; that Russia not pay war reparations. It is counterproductive and unjust to make concessions in advance in exchange for nothing — and especially to make them in the name of other people.

Ukrainians must be heard. Officials of the Russian aggressor state are happy that their position is the basis of the US proposal. Americans should listen to Ukrainians. The Russians know why they invaded Ukraine. They know how they believe they can dominate Ukraine and destroy its independence. There is little sign that this administration has registered that these are Russia’s goals or understands enough about how the Ukrainian and Russian states function to recognize the danger. If Ukrainians are not allowed to point out the obvious, not only they but all of us will suffer. In earlier posts I go into detail on the issues.

Settlements that exclude relevant parties are unlikely to succeed. After the First World War, countries that were deemed aggressors were essentially excluded from the meaningful part of the negotiations. There were other sources of the Second World War, but this was one of them. The situation today is much more dramatic: the country that is obviously the victim, Ukraine, has been excluded. Which leads to:

It matters how the war started. Since the Second World War, a basic principle of international order has been that aggression to change state borders is illegal. A settlement that rewards Russia weakens international order and makes future war more likely. A settlement that defends Ukraine does the opposite: it strengthens world order and makes future war less likely.

Nuclear war would be a bad outcome. By resisting Russia successfully, Ukraine makes the risk of nuclear war much lower. But if Ukraine is seen to be defeated (for example, by being forced into an unjust settlement), other countries, in Europe and Asia, will draw the conclusion that they need to build nuclear weapons to deter a future Russian (or Chinese) invasion. This is already widely discussed and is generally known. Nuclear proliferation will lead to a far more dangerous world, and a mathematically greater chance of nuclear war. To prevent this, Ukraine must be seen by the wider world as having defended itself successfully. That is a reasonable check on any proposed settlement.

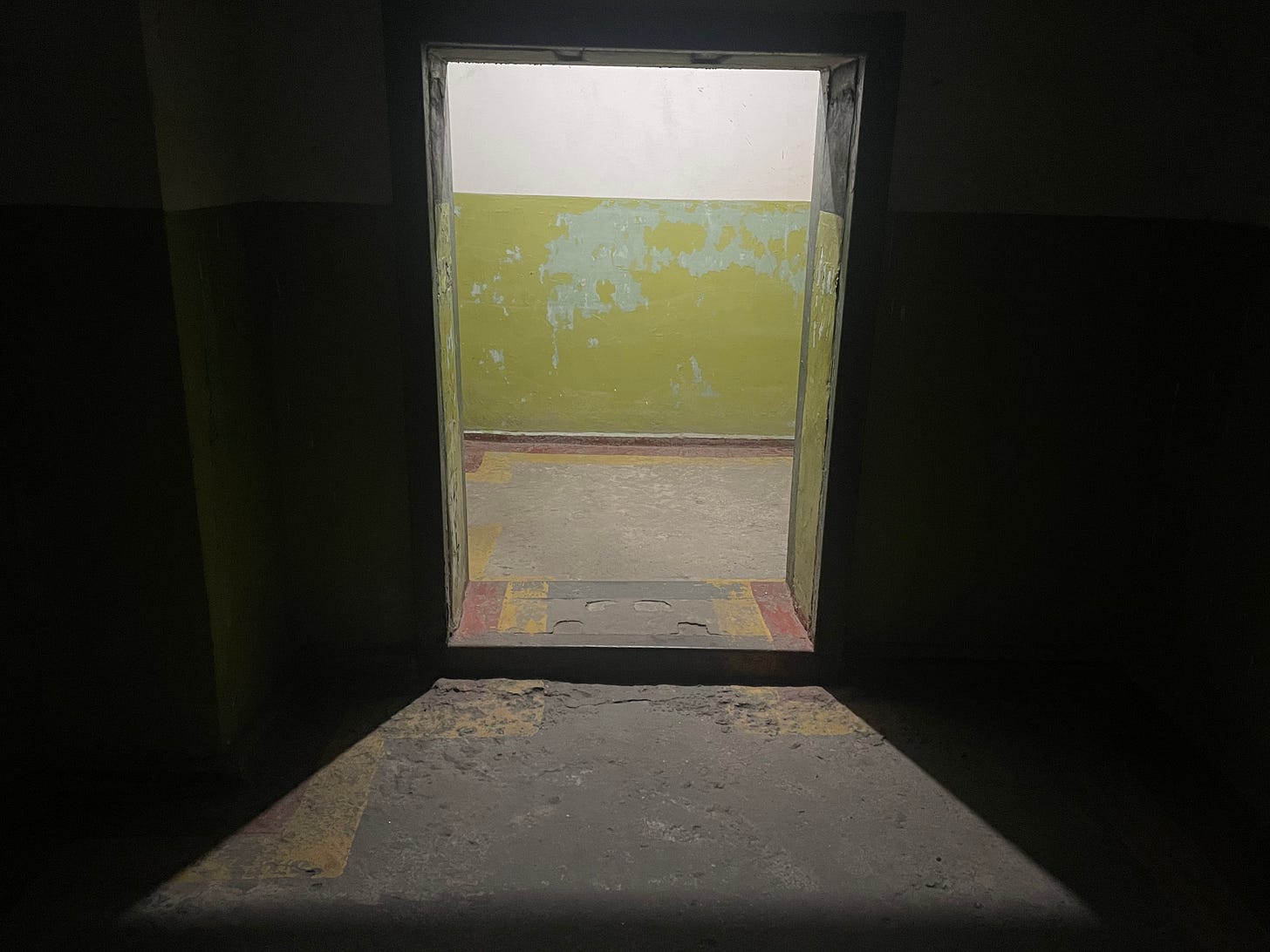

A cold-war-era bomb shelter in Nikopol, Ukraine. Built for nuclear war, it has been adapted as a shelter for factory workers targeted by Russian missiles and drones. Photo TS September 2025.

Participants should account for their own vulnerabilities. President Trump’s desire to win the Nobel Peace Prize is perhaps the best-known emotional vulnerability in the history of international relations. But if this desire leads to a hasty and ill-considered attempt at a peace settlement, the war will only get worse. The Russians will be all too happy to support a PR campaign for Trump to get the prize even as they escalate their war against Ukraine after an unwise attempt at settlement.

The politics inside countries matter. Democracies are different that tyrannies, and fight for different reasons. Russia is fighting because Putin has personal ideas about his place in history and so on. Ukraine is fighting because Ukrainians do not wish to be subjugated. It follows that inducing Ukraine to end the war has to involve the Ukrainian people, and not just President Zelens’kyi. The US administration seems to proceed from the premise that the war is essentially a kind of real estate disagreement between two men. But Ukrainians are not fighting for Zelens’kyi. They are fighting for their lives and for a sense of what a decent life means. Although we might do so, they cannot forget mass murder campaigns, mass torture, and the mass kidnapping of children. “Security guarantees” are therefore not an abstraction.

Enforcement mechanisms are necessary. Russia has violated every agreement it has ever made with Ukraine. Assurances from Moscow that Russia will not attack are worse than meaningless. Assurances that we we will somehow help are also without substance — we gave such assurances in 1994 when Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons, and they did not help. Enforcement mechanisms mean actions that are automatically triggered by new Russian aggression. And that is really only possible within institutions. Ukrainians are right to want to join NATO. It is a meaningful security guarantee. Russia attacks countries that are not NATO members. It does not attack countries that are NATO members.

For Ukraine, the crucial concept is sovereignty. As it is for Russia: the aim is to ensure that this war leads to a situation in which there is no sovereign Ukrainian state. This means that negotiators have to be very sensitive to avoid any Russian intrusion on Ukrainian domestic politics: like, for example, demanding changes to the constitution, or demanding that this or that law be passed. On the other side, it also means that negotiators have to respect the basic elements of a country’s foreign police: to choose its own allies; to decide whether foreign troops are stationed on its territory; to make its own defense or foreign policy. A settlement that does not respect Ukrainian sovereignty in these basic ways will would be not only illegal and unjust: it would reward Russian aggression in the most fundamental way, guarantee more of it, and destabilize the region and the world.

Peace is more than the absence of hostilities at a given moment. Peace has to mean that Ukraine rebuilds. If the reconstruction of Ukraine is not at the center of a peace settlement, the peace cannot hold. Reconstruction will involve huge business opportunities for Ukraine’s allies — far more meaningful and predictable than anything available in Russia. Ukraine needs long-term aid to its non-governmental organizations, to its regions, and to its central government, as well as membership in the European Union. This is not something that can be achieved if negotiators are in a hurry. And of course it requires the participation of all of Ukraine’s allies.

In an earlier post, I went into some detail about the likely issues — in greater detail than here. In an earlier video, I discussed some of the underlying problems of negotiating with Russia. I am hoping that this essay will be clarifying amidst the present confusion.

This war can be brought to an end, but the basic logic remains what it always was: the Ukrainians have to be supported so that Russia no longer aspires to destroy their country. That is the foundation. Negotiations will work when that has been achieved.

Thinking about… is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

For positive solutions see On Freedom

Julia Davis’s book In Their Own Words

From Thinking about… via this RSS feed