![]() ⏵ Listen to Opinião - As Cantadeiras

⏵ Listen to Opinião - As Cantadeiras

[Listen to ‘Opinião’ by Zé Keti, who became a symbol of resistance to Brazil’s dictatorship. He was featured in Augusto Boal’s 1964 post-coup show that called for unity between rural workers, the urban poor, especially Black communities, and politicised middle-class sectors. This recording is by the MST band, As Cantadeiras.]

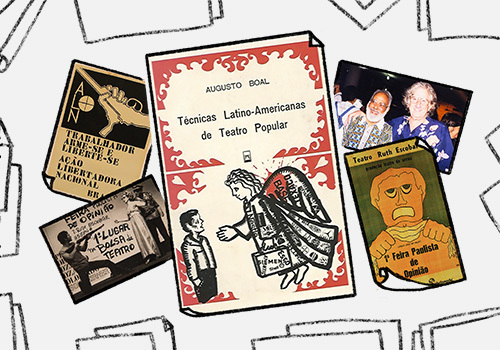

While in exile fifty years ago, in 1975, the Brazilian theatrologist Augusto Boal published Técnicas Latino-americanas de teatro popular (‘Latin American Techniques of Popular Theatre’), a book released just months after his world-renowned classic, Theatre of the Oppressed. While the latter would project Boal to the global stage, Técnicas has remained untranslated into English and largely unknown to audiences beyond Latin America.

As Julian Boal, a teacher, researcher, and theatre practitioner who worked alongside his father for two decades, said in a conversation with us, it is a book with ‘a subterranean legacy’ whose radical ideas have been ‘little published’. To revisit Técnicas today is not an act of mere historical curiosity; it has a political impetus. The book is not a footnote to Theatre of the Oppressed but has its rightful place as a foundational document of cultural struggle in Latin America and beyond, guided by its provocative subtitle: uma revolução copernicana ao revés (‘a Copernican revolution in reverse’).

Building a Popular Latin American Theatre for Liberation

![]()

Boal’s ‘Primeira Feira Paulista de Opinião’ theatre spectacle during Brazil’s military dictatorship (1968).

Augusto Boal’s theatre was not born on bourgeois stages nor in university lecture halls; it was forged in the heat of class and anti-imperialist struggle. His theoretical formulations were the direct result of his lived militancy, a praxis developed to meet the urgent needs of a revolutionary movement. Before his exile, Boal was a part of the so-called ‘network of collaborators’ of Ação Libertadora Nacional (ALN), a Brazilian armed struggle organisation resisting the US-backed military dictatorship. For this work, he was arrested, imprisoned, and brutally tortured in 1971, an experience that marked him and his work indelibly.

His political formation began much earlier, working in the 1950s with Abdias do Nascimento, the founder of Black Experimental Theatre. Through Nascimento, a leading figure of the Pan-Africanist movement in Brazil, Boal was steeped in the anti-colonial traditions of Négritude, drawn from thinkers such as Aimé Césaire and Léopold Sédar Senghor. This grounding in Black liberation struggles provided a crucial anti-racist and anti-colonial foundation for his later work.

Boal’s personal journey was inseparable from the era’s seismic political shifts. The 1959 triumph of the Cuban Revolution sent shockwaves of hope across the region. This new energy culminated in the 1966 Tricontinental Conference in Havana, which brought together delegates from 82 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America to forge a common front against imperialism. From the Tricontinental emerged the Organización Latinoamericana de Solidaridad (OLAS – Latin American Solidarity Organisation) in 1967, an initiative of President Salvador Allende. It was after attending an OLAS meeting in Cuba that Carlos Marighella returned to Brazil to found the ALN, the very organisation Boal would join. Boal was not an artist observing politics from the sidelines; he was a cultural worker embedded in a revolutionary current that flowed directly from Havana. His exile, forced upon him by the dictatorship, was not a retreat but a strategic redeployment that continued until 1975. During his travels across Latin America, he deepened his theatrical concepts through direct contact with the continent’s social struggles.

![]()

Left: ALN poster (c. 1960s); Right: Abdias Nascimento and Augusto Boal (2000).

During his exile, Boal did not work in isolation. He documented and helped to build a collective, internationalist movement – a ‘continental project’ as Argentine historian Marina Pianca calls it in El teatro de nuestra América: un proyecto continental, 1959–1989. This project sought to construct a ‘new culture’ for a new, liberated Latin America. A key arena for this project was the Latin American Theatre Festival of Manizales in Colombia, which began in 1968. For Boal, as he writes in Técnicas, Manizales was more than a festival; it was the ‘first possibility of dialogue between Latin American groups’ and, more pointedly, the ‘battlefield between Latin American theatre and colonialist theatre’.

What began at Manizales as a site of encounter and debate soon matured into a structured political body. This process of articulation, which spanned national and international meetings across the continent, reached its height in 1974 with the consolidation of the Frente de Trabalhadores da Cultura de Nuestra América (Front of Cultural Workers for Our America). The evolution from a festival to a front signified a profound leap in political consciousness and organisational capacity. This was not an ad-hoc network but the deliberate construction of a revolutionary cultural infrastructure, a parallel ecosystem built by and for the people, outside the confines of bourgeois state theatres and commercial circuits.

The front’s scope was truly continental, embodying José Martí’s ideal of ‘Nuestra América’ (‘Our America’). It incorporated the Chicano theatre movement from the United States, the teatro campesino (‘rural theatre’) of Mexico, and groups working with indigenous peoples and in the Caribbean. This vast network was sustained by its own institutions. A Permanent Committee of International Festivals was created to ensure continuity, and the Cuban magazine Conjunto, published by the prestigious Casa de las Américas, became what Boal called a kind of central organ for the movement.

Becoming the Centre of our Artistic Universe

![]()

Left: Cover of first Portuguese edition of Técnicas (1977); Right: Fidel Castro’s closing speech at the Cultural Congress of Havana (1968).

At the heart of Técnicas is the ‘Copernican revolution in reverse’ which unfolds in two simultaneous, interconnected movements: one geopolitical, the other aesthetic.

The first inversion was a radical reorientation of the continent’s cultural geography. For centuries, Latin American art had been defined by its relationship to the colonial and neocolonial metropoles of Europe and the United States. For Boal, Latin American and Caribbean countries that had been ‘satellites of metropolitan art’ would be the ‘centre of our artistic universe’. This was a declaration against ‘cultural colonialism’, a fight for cultural sovereignty waged on the ‘battlefield’ of Manizales. This struggle was ideologically nourished by the 1968 Cultural Congress of Havana, the debates of which inspired Boal when he visited Cuba shortly after. The congress, itself an offshoot of the Tricontinental Conference, issued resolutions condemning the new and old techniques by which ‘imperialism sharpens every day more the effort of cultural colonisation and neocolonisation’.

This new, self-centred universe was not isolationist; it was internationalist, in solidarity with other Third World nations. The symbolic reference of Vietnam was immense. In Técnicas, Boal includes a journalist’s report on a performance by a theatre group from the National Liberation Front (FNL) of Vietnam for an audience of 6,000 people. This was a conscious act of alignment, linking the Latin American struggle to the heroic resistance of the Vietnamese people and echoing the call by Che Guevara in his letter to the Tricontinental Conference to create ‘two, three, many Vietnams’.

Spectators Must Also be Producers

![]()

Augusto Boal training MST militants (2005).

The second inversion was an aesthetic one. Boal argued that true cultural decolonisation required a revolution in the relationship between the artist and the people. If, before, artists occupied the centre of the relationship with the public, he insisted, ‘now it must be the opposite, the spectator (the people), must be the centre of the aesthetic phenomenon’.

Not a liberal plea for more audience participation, this was a revolutionary dismantling of the separation between the producer and the consumer of art, between the active creator and the passive spectator. ‘Spectators must also be producers’, Boal declared. The role of the popular artist was transformed: ‘the true popular artist is the one who, besides knowing how to produce art, must know how to teach the people to produce it’. This leads to the book’s central thesis, a direct application of Marxist principles to the field of culture: ‘what must be popularised is not the finished product but the means of production’.

These two revolutions are dialectically inseparable. Boal understood that there would be no cultural liberation without popular liberation. Similarly, there could be no cultural liberation in one country, without it being connected with an international anti-imperialist struggle. True liberation demands a simultaneous advance on both fronts: the people must seize the means of cultural production to break the cultural dominance of the metropolis.

Boal’s Legacy for Today’s Global South

![]()

International Theatre Meeting at the MST’s Florestan Fernandes National School, including Julian Boal (2016).

Fifty years on, Boal’s Copernican revolution is more relevant than ever. His project is not a historical curiosity but a living praxis for the struggles of our time. As Julian Boal argues, the task for movements of the Global South today is not merely to appropriate the existing means of production but to fundamentally transform them, to reinvent them so that their potential emancipatory aspects become truly effective.

Nowhere is this living legacy more apparent than in the work of Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement (MST), which has undertaken a project to re-edit and publish Técnicas Latino-americanas de teatro popular, demonstrating that its themes still resonate powerfully on the frontlines of the class struggle. The MST understands that its fight is not just for land, but for a new society and a new culture built on that land. The experiences of the Network of Theatre Schools of Nuestra América – organised in part by the MST across the continent – offer another example of the lasting influence of this project.

In the 1970s, Boal described theatre as a rehearsal for the revolution, a way for movements in opposition to prepare for the seizure of power. Today, the challenge for Global South countries, perhaps less steeped in the revolutionary spirit of liberation, is still carrying on the unfinished project of transforming the international world order – to see this Copernican revolution in reverse carried to its inevitable conclusion, in which the peoples of the Global South can seize the stage to write and perform their own history.

![]()

Patrice Lumumba exhibition in Venezuela (2025).

In Other News…

On 2 July, to mark the centenary of Congolese revolutionary, Patrice Lumumba, the Venezuelan Foreign Ministry organised an event to celebrate the African independence hero, including an exhibition organised by Utopix, including artwork from our institute. Speakers, including Foreign Minister Yvan Gil and Lumumba’s son Ronald, highlighted Lumumba’s legacy, and its relevance for today’s struggles. View Lumumba’s portrait and others featured in our July gallery.

Warmly,

Douglas Estevam, member of MST’s National Culture Collective and the Political Pedagogical Coordination of the Florestan Fernandes National School

Tings Chak, Art Director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

From | Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research via this RSS feed