This editorial by Jaime Ortega originally appeared in the November 18, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Mexico Solidarity Media*, or the Mexico Solidarity Project.*

Alain Rouquié said that the term “fascist” revealed more about the person using it than about what they were trying to describe. Indeed, the productive explosion of Latin American social sciences during the 1970s had as one of its central axes the analysis of processes considered fascist. Much of the intellectual energy was focused on deciphering a set of high-intensity political phenomena: military dictatorships. To this end, terms like “dependent,” “creole,” or “underdeveloped” were used. In the theories of the time, it was key to link the notion of capital accumulation with the violent and repressive onslaught of various governments. This was how they sought to understand extreme phenomena such as those led by Duvalier, Somoza, and Trujillo, but also the modernized and ruthless juntas in Chile, Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay.

The array of figures who participated in that debate was impressive: Vania Bambirra, Theotonio dos Santos, Hugo Zemelman, Helio Jaguaribe, Darcy Ribeiro, Marcos Kaplan, Agustín Cueva, Juan Bosch, Alvaro Briones, René Zavaleta, Gerard Pierre-Charles, Suzy Castor, Ruy Mauro Marini, Clodomiro Almeyra, Cayetano Llobet, Eduardo Galeano, and Pedro Vuskovic, as well as the communists Rodney Arismendi and Luis Corvalán. Given the number of authors and the diversity of cases, reaching even minimal consensus was difficult. However, some elements emerged as essential for arguing for or against the use of this category. In this regard, it is striking that in his Late Fascism, Alberto Toscano promises to revisit the discussions of that decade, but completely avoids the Latin American perspective, despite its productivity.

The central theme of the reflections of that group of prominent figures revolved around the mass movement nature of historical fascism, especially the impact of the so-called “petty bourgeoisie.” This was one of the elements on which there was the least agreement, since, with the exception of the Chilean case, there was no significant social mobilization among the experiences analyzed. Secondly, attention was focused on the specific operations of these governments, centered on the extreme use of terrorist and illegal violence; on this point, there was undeniable agreement. Finally, the third element concerned the subordinate integration of these governments into the global economy, such that the “fascist” forms in the region differed substantially from those of the 1930s, as they were not expansionist or ultranationalist, but rather products of dependency.

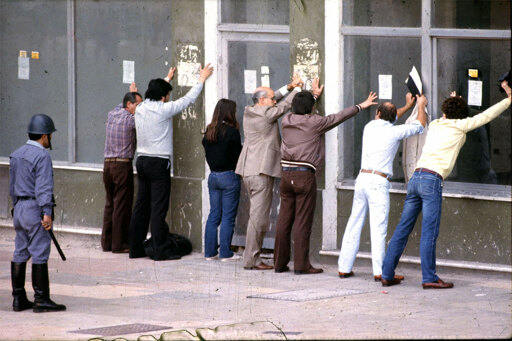

Estadio Nacional de Chile concentration camp, Santiago, 1973

The multiplicity of proposals was accompanied by a political perspective that diverged between those who envisioned revolution as the only response to right-wing processes and those who emphasized the need for a Popular Front process, with broad alliances to restore basic democratic agreements. It is paradoxical that, despite the fact that some of these discussions took place in Mexico, authors from our country, especially those on the left, made little use of this category.

In this context, the magazine Nueva Política is striking, its sixth issue titled: Fascism in Latin America. Such are the paradoxes of the political climate: while Latin American authors used the term to frame it as a “reform or revolution” dichotomy, in Mexico the situation was quite different. Some of those who contributed to that publication had recently declared their political support for then-candidate Luis Echeverría, under the slogan “Echeverría or fascism.” Thus, in the 1970 election, the PRI had resorted to the fascist tactic as a way to close ranks, as Enrique Semo critically explained a few years later. Although the Marxist historian acknowledged the existence of fascist groups in society, he saw neither mass influence nor the sympathy of the oligarchies: “By raising the specter of fascism in Mexico, the spokespeople for the PRI are taking advantage of pressure from imperialism and its local associates to breathe new life into the right-wing monster,” he warned.

Revisiting those discussions is significant, as it allows us to draw the lines of demarcation with respect to our present. Today, right-wing experiences are diverse, with little homogeneity in their economic programs, appealing to sectors that extend beyond large financiers and the “middle classes.” However, what is most striking about them is the absence of a vision for the future, since their activation is a result of nihilism, of which they are also victims. Thus, today’s right-wing movements resort to the past as a destructive nostalgia, wield power without a clear guiding principle, and employ irrational violence in their role as the opposition. However, as the intellectuals of the 1970s did, it is necessary to delve deeper than general perspectives and fully engage with local contradictions, because the right wing is not exempt from the national imprint that evokes contemporary times, becoming both heirs to and participants in a history they did not choose, but which also shapes them.

Jaime Ortega is the Director of Memoria, the Magazine of Militant Criticism, a researcher at UAM, and the author of La raíz nacional-popular: las izquierdas más allá de la transición.

The Category of Fascism & the Latin American Debate

November 20, 2025November 20, 2025

Today, right-wing experiences are diverse, with little homogeneity in economic programs, appealing to sectors extending beyond large financiers & the “middle classes.” However, what is most striking about them is the absence of a vision for the future.

Soberanía 85: Exposing the Astroturf ‘Gen Z’ Protest in Mexico

November 19, 2025

The truth behind what was billed as a “youth” march and instead was a by-the-book, attempt at astroturfed destablization.

Reducing Inflation with Cheap Imports is Costly

November 19, 2025November 19, 2025

Mexico’s imports are equivalent to 48% of agricultural production, resulting in a year-on-year loss of food sovereignty and a greater dependence on capital inflows which benefits the financial sector at the expense of national public & private sectors.

The post The Category of Fascism & the Latin American Debate appeared first on Mexico Solidarity Media.

From Mexico Solidarity Media via this RSS feed