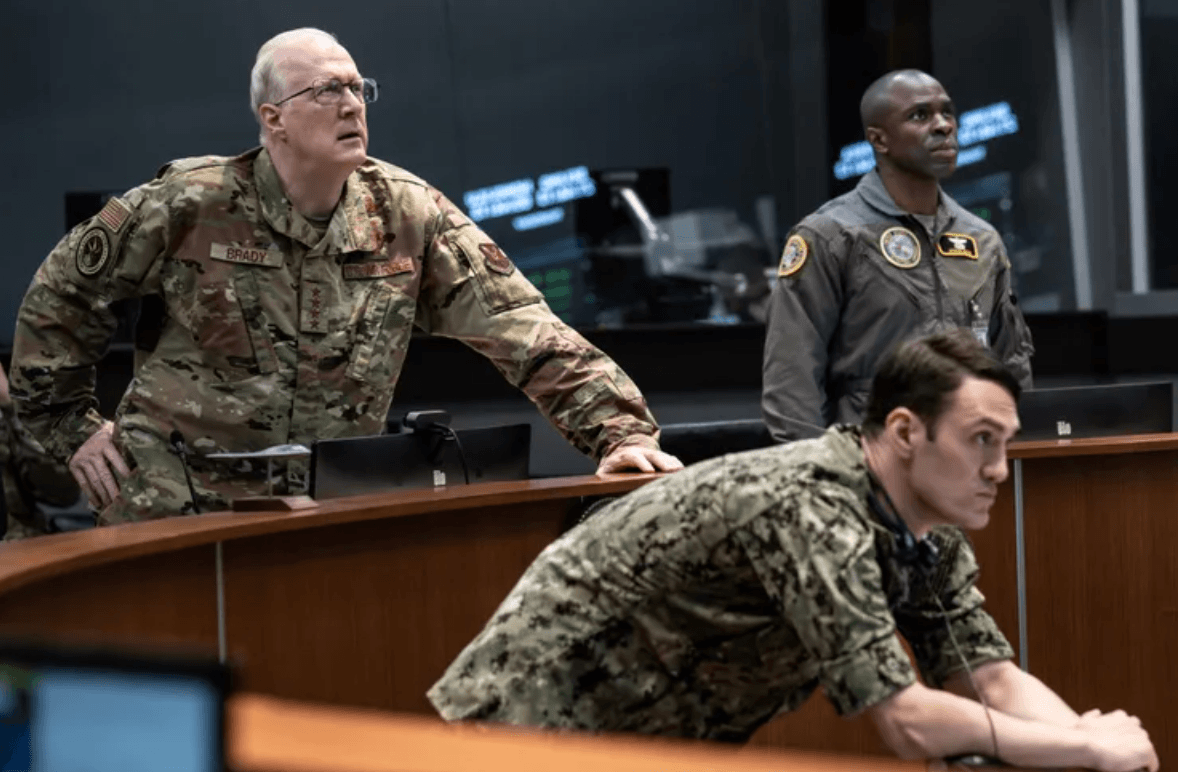

Still from A House of Dynamite.

Kathryn Bigelow is back, and not much has changed. Eight years since her last feature film, the first woman to win the Best Director Oscar for her unwavering depiction of the trauma of the occupier, the American filmmaker has made yet another war film – one that, like The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty, is seeped in the language of responsibility, yet, like those movies, remains problematic at its core.

A House of Dynamite arrives dressed as an anti-war, anti-nuclear weapons story. It claims to confront the horror of nuclear weapons with clear-eyed realism – to show, without melodrama, the suddenness with which the world could unravel. But peel back the surface and the film reveals something far darker: a work of imperial fantasy, a fever dream – wholly detached from any semblance of political reality – in which the United States imagines itself as the victim of the bomb it invented.

The film’s plot is absurd. It imagines a nuclear strike on the US – a missile bound for Chicago, which will wipe out the city and kill ten million people in the blink of an eye. It’s a fantasy that might have made sense in the 1960s, at the height of Cold War paranoia after the October Crisis (Cuban Missile Crisis). In 2025, however, it borders on delusion. No nation on Earth could, or would, launch a nuclear attack on the US. In fact, the only country ever to have used atomic weapons against civilians is the US itself – and not once, but twice. Yet Bigelow asks us to imagine – in 2025, no less – that the empire which annihilated Hiroshima and Nagasaki now trembles beneath its own mushroom cloud.

This inversion is not new to the veteran filmmaker. Bigelow has always filmed the machinery of empire with reverence. In Zero Dark Thirty, torture is procedural, and the lives of Pakistani civilians are afterthoughts – objects in the way of the US manhunt for Bin Laden; collateral ultimately rationalised by the ends. In The Hurt Locker, war is stripped of history and turned into a soldier’s addiction. A House of Dynamite continues the same project but with a slightly different disguise. Gone are the overt symbols of triumphalism or battlefields; in their place, a solemn tragedy. The film mourns American fragility so earnestly that the terror of annihilation becomes one more opportunity for self-mythology.

It follows officials, generals, and analysts struggling to save the homeland, all from different perspectives, which ultimately collapse into the same one anyway. Even as these people repeatedly make comments about how this could spell the deaths of hundreds of millions around the world, the US is all we see. Beyond a token exchange with Russia’s foreign minister, the rest of the world ceases to exist for the duration of the film’s almost two-hour runtime. No one asks what would happen to Pyongyang, Tehran, or Beijing if a nuclear war began; the only catastrophe worth filming is American. The empire’s imagination, it turns out, cannot stretch beyond its own borders. Even at the end of the world, the camera never leaves Washington.

This claustrophobic gaze serves a purpose. By erasing everyone else from the frame, the film plays on the fears baked into American exceptionalism. And so, the dread of sudden obliteration it imagines is less an argument against nuclear weapons and more for endless defence spending. Early in the story, a $50 billion missile-interception system is introduced. It has a 61 per cent chance of success, according to the film. “A coin toss,” as the viewer is constantly told. When it fails, the not-so-subtle implication is this: even as millions of Americans struggle to live paycheck to paycheck, without access to healthcare, the billions going towards the war machine are necessary because what if, one day, an adversary decides to nuke us on a whim?

This logic comes at a time when militarism, in the eyes of the US public, is waning. The US military faces plummeting recruitment, record scepticism, and rising outrage over its global conduct – at the core of which lies its facilitation of Israel’s genocidal assault on Gaza. Within this climate, A House of Dynamite functions as a cultural triage designed to resuscitate faith in the institution by reminding Americans of their supposed vulnerability. Want to protect your family from the next imaginary nuke? Well, you’d better keep funding the war machine that is currently incinerating fishermen in the Caribbean.

Part of what makes the film so insidious is how convincingly it moves. Bigelow’s realism – her eye for detail and her fluency in military ritual – is well regarded. This gives every frame in A House of Dynamite a sheen of authenticity, especially for those unfamiliar with the politics of empire. It is also why Bigelow has long enjoyed privileged access to the security state. The procedural accuracy of Zero Dark Thirty, for example, famously benefited from CIA cooperation. “We really do have a sense that this is going to be the movie on the UBL [Bin Laden] operation – and we all want the CIA to be as well-represented in it as possible,” stated an internal email sent from the CIA’s Office of Public Affairs in June 2011, about that movie. This is how modern propaganda works, not through flag-waving, but through immersion. The more “authentic” it feels, the less you question the fantasy. It is why Zero Dark Thirty retains credibility and reverence among the liberal elite and American critics, and Red Dawn doesn’t.

When A House of Dynamite reaches its climax, the unnamed POTUS (Idris Elba) must decide how to retaliate after the $50-billion coin-toss fails. An adviser mutters to the president about “bad guys” – the script’s actual term, believe it or not – for the possible culprits. The president hesitates, reluctant to start a nuclear holocaust yet seemingly forced to defend the US. Bigelow stages the moment as tragedy, but the politics are obscene. The implication is that even the contemplation of mass murder is a uniquely American burden. There is no anti-war message here, only the self-flattering belief that US violence, even nuclear annihilation, would be reluctant, and therefore righteous.

By the time the film reaches its conclusion, A House of Dynamite has achieved something almost admirable in its cynicism. It transforms a fantasy of impossible destruction into moral theatre. It asks us to sympathise with the empire’s fear while ignoring the empire’s victims. This is propaganda for an age of liberal despair. The danger is never what America does. The danger is what might happen to America.

For all its talk of “the human cost”, A House of Dynamite never imagines a human outside the frame of the US flag. And to put this movie out now – while Gaza starves under American bombs, while arms manufacturers post record profits – is to see how seamlessly culture serves capital. The mushroom cloud over Chicago is fiction; the bombs over Fallujah and Rafah are not.

The post H: Kathryn Bigelow’s Empire of Fear appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed