Still Life by Meredith Frampton

Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital. In The Times this week I wrote about early 2020s cancel culture. At the time we all obsessed about a “culture war” and a “moral revolution”, but in hindsight a lot of what really drove high profile cancellations was just professional envy and resentment.

I also spoke to the splendidly-named Smart Cookies podcast about my perennial theme: how the internet is destroying our minds.

The Decline of DevianceThis enjoyably illustrated essay by Adam Mastroianni argues that people are “less weird than they used to be”. Society is suffering “an epidemic of the mundane”. People are better behaved, less sexually active, less likely to join cults, more likely to wear seat belts and less likely to move to another part of the country.

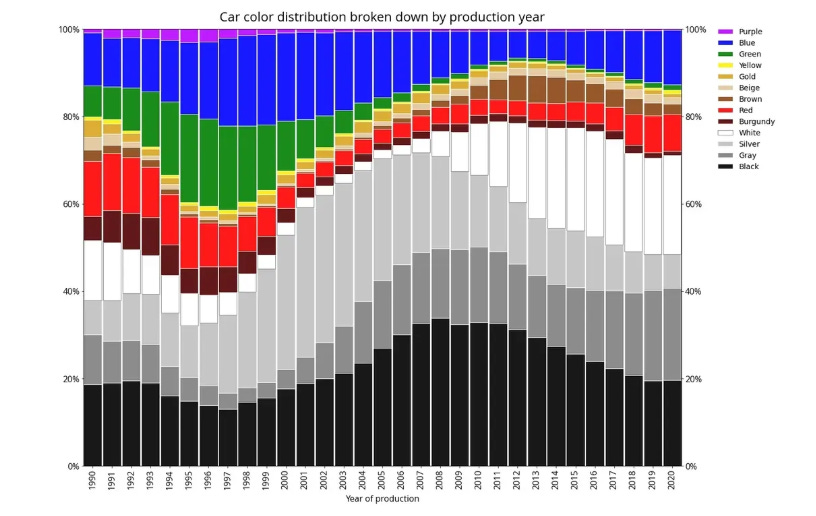

Aesthetics is converging on a kind of bland minimalism: company logos are getting less elaborate, book cover design is converging on a samey aesthetic and even corporate websites look like clones of each other.

Music is becoming more homogeneous and repetitive. Franchise films rehash the same characters and themes. All influencers apparently sound the same — the (new to me) phenomenon of the “influencer accent”. According to the New York Times:

We are now almost a quarter of the way through what looks likely to go down in history as the least innovative, least transformative, least pioneering century for culture since the invention of the printing press.

People are even buying less colourful cars. Black, white and grey have swamped the market. Burgundy (once more popular than white) has been all-but obliterated.

This is all good fun but I’m not sure how far I buy it. It may be that the physical world is becoming more conformist as our internal worlds become more bizarre: conspiracy theories, extreme politics, everyone living in their own hyper-individualised cultural niche etc. Derek Thompson’s “monks in the casino” phenomenon writ large.

We are never going to outer spaceThis entertainingly deflating piece argues that although we tend to look at science fiction fantasies of space flight and interpret them as visions of our species’ future, they are far more outlandish and magical than anything in Lord of the Rings.

We are much more likely to invent magic wands or live among dragons than to work out how to master interstellar flight which is virtually a scientific impossibility:

The ships in Star Trek, Star Wars, Dune etc. are not based on some kind of hypothetical technology that could maybe exist someday with better energy sources and materials. In every case, their tech is the equivalent of just having Albus Dumbledore in the engine room cast a teleportation spell. Their ships skip the vast distances of space entirely, arriving at their destinations many times faster than light itself could have made the trip. Just to be clear, there is absolutely no remotely possible method for doing this, even on paper.

Nobody really grasps how big space is:

The reason space operas rely on literal magic to make their plots work is that there is no non-magic way to get over the fact that stars are way, way farther apart than the average person understands. Picture in your mind the distance between earth and Proxima Centauri, the next closest star. Okay, now mentally multiply that times one billion and you’re probably closer to the truth. “But I can’t mentally picture one billion of anything!” I know, that’s the point. The concept of interstellar travel as it exists in the public imagination is based entirely on that public being physically incapable of understanding the frankly absurd distances involved.

Travelling to our closest star, Proxima Centauri, at current space ship speeds would take half a million years, one hundred times longer than the entire of recorded human history. To get a ship large enough to sustain life to go at the kinds of speed depicted in sci-fi films would “require far more energy than the total that our civilisation has ever produced”. Oh well.

Never going to happen

The age of stupidNew York Magazine’s latest edition is disarmingly titled ‘The Stupid Issue’. In the cover story the magazine’s feature writer Lane Brown makes the case that we are indeed living though the Age of Stupid.

The most remarkable piece of evidence is the reversal of the so-called Flynn effect which describes the way IQ rose consistently throughout the twentieth century.

IQ is now declining. Recently Elizabeth Dworak analysed the results of 394,378 IQ tests. Her data,

showed declines in three important testing categories, including matrix reasoning (abstract visual puzzles), letter and number series (pattern recognition), and verbal reasoning (language-based problem-solving). The first two, in which losses were deepest, measure what psychologists call fluid intelligence, or the power to adapt to new situations and think on the fly.

This point about the disappearance of the stigma around ignorance is a good one:

It’s not just that children have been bombing their standardized tests (ACT scores are at their lowest in more than 30 years, and high-school seniors’ average math scores in a national exam were the lowest since 2005) or that more than a quarter of U.S. adults now read at the lowest proficiency level. It’s also that in nearly all aspects of life, we’re opting for routines, entertainment, and entire belief systems that ask less and less of our brains. The stigma that was once attached to ignorance has disappeared, and the loudest and least informed voices now shape the conversation, forcing everyone else to learn to speak their language.

It wasn’t very long ago that educated middle class people used to feel some shame about watching television. Obnoxious and pretentious in some respects but it probably served to shape better media consumption habits. Nowadays I don’t think people feel any embarrassment at all about watching hours of trivial and infantilising short form video. Maybe snobbery had its uses.

Meanwhile in China…This piece in The Baffler makes some similar arguments about the importance of literacy to civilisation to the ones I put forward in the essay I wrote a few months ago, ‘The Dawn of the Post-Literate Society’. It adds some interesting details. Including this one:

Because China is ruled by an ostensibly Marxist cadre, the country has an ability to restrict electronic opiates far beyond anything an American could imagine. In 2019, China limited under-eighteen-year-olds to ninety minutes of video games a day. In 2021, this was limited to one hour on Fridays, weekends, and holidays, between 8 and 9 p.m. Similar restrictions time-limit youngsters from spending more than 2.48 hours a day on scrolling video.

Meanwhile, a report in The Times a few weeks ago found that British teenagers spend more time playing video games every week than they spend at school. At some point this disparity is going to become a serious problem for the West. Maybe it already is.

Humans are quite niceHuman beings are often compared to their chimpanzee cousins. We are so closely related to chimps and look so similar to them that it seems natural to draw comparisons between chimp behaviour and human behaviour.

This interesting piece by Ed West outlines a strand of thought which holds the comparison is overdone. Humans are extremely social and in many ways closer to other herd animals or co-operative insects like ants or bees.

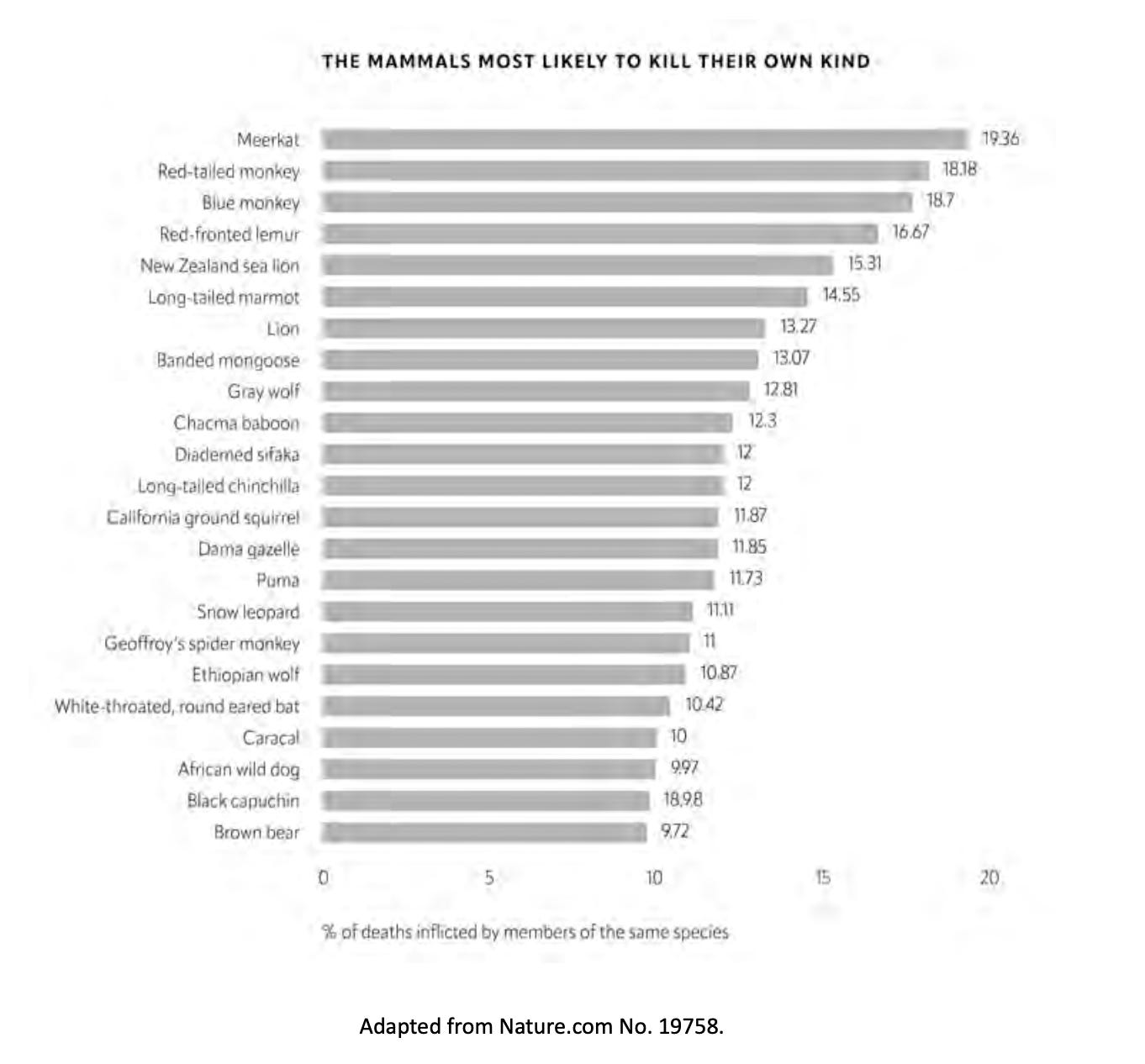

Chimpanzees are violent, unempathetic and uncooperative. Humans, by comparison, are relatively sociable and peaceful. Bonobos — to whom humans are often compared — “are one hundred times as likely as people to engage in physical violence”, Meanwhile:

Humans, in contrast, do not even rank in the top 30 of species who kill their own kind [I assume we’re speaking per capita here], despite the toll of wars. One reason for this relative docility is that our brains have evolved a strong sense of empathy towards other humans, and with it a revulsion to taking innocent life.

Beware meerkats

PhilistinismI have been just loving Vladimir Nabokov’s Lectures on Russian Literature. Nabokov, as I remember every time I read him, is probably my favourite writer. I love his archness, his semi-self-parodying snobbery and (obviously) his very beautiful prose. The lectures aren’t as dazzlingly polished as Pnin or Lolita but they are scattered with enjoyable ironic extravagances, little jokes at the inherent pomposity of lecturing. At one point he calls the nineteenth century a “resplendent orb”.

Nabokov’s tenderly and acutely appreciative chapters on Chekhov and Tolstoy are some of the most enjoyable literary criticism I think I’ve read. Rather than labouring through the books via themes or symbols or theories, he simply guides you through the plot of Anna Karenina or ‘The Lady With the Dog’ pointing out particular landmarks of genius as you go. His lecture on Dostoevsky is entertainingly hostile.

At the end of the book there is a short lecture on philistinism which Nabokov used to deliver annually to his students at Cornell as a warning:

The philistine likes to impress and he likes to be impressed, in consequence of which a world of deception, of mutual cheating, is formed by him and around him. The philistine, in his passionate urge to conform, to belong, to join, is torn between two longings: to act as everybody does, to admire, to use this or that thing because millions of people do; or else he craves to belong to an exclusive set, to an organization, to a club, to a hotel patronage or an ocean liner community (with the captain in white and wonderful food), and to delight in the knowledge that there is the head of a corporation or a European count sitting next to him. The philistine is often a snob. He is thrilled by riches and rank—”Darling, I’ve actually talked to a duchess!”‘

It is amazing how easy it is to think of people who fit this description one way or another. I guess philistinism is an unchanging human trait (perhaps one that is even increasing). Donald Trump is perhaps the apotheosis of the type.

Nabokov illustrated his lecture with this advertisement which he called “the adoration of the spoons”

Until next week!

James

Thanks for reading Cultural Capital! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

From Cultural Capital via this RSS feed