A voluntary plan to curb fossil fuels, a goal to triple adaptation finance and new efforts to “strengthen” climate targets have been launched at the COP30 climate summit in Brazil.

After all-night negotiations in the Amazonian city of Belém, the Brazilian presidency released a final package termed the “global mutirão” – a name meaning “collective efforts”.

It was an attempt to draw together controversial issues that had divided the fortnight of talks, including finance, trade policies and meeting the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C temperature goal.

A “mechanism” to help ensure a “just transition” globally and a set of measures to track climate-adaptation efforts were also among COP30’s notable outcomes.

Scores of nations that had backed plans to “transition away” from fossil fuels and “reverse deforestation” instead accepted COP30 president André Corrêa do Lago’s compromise proposal of “roadmaps” outside the formal UN regime.

Billed as a COP of “truth” and “implementation”, the event – which took place 10 years on from the Paris Agreement – was seen as a moment to showcase international cooperation.

Yet, the lack of consensus on key issues and rising salience of “unilateral trade measures” and financial shortfalls revealed deep divisions.

The event itself also faced numerous logistical challenges, including a lengthy delay to negotiations when a fire broke out, forcing thousands of attendees to evacuate.

Here, Carbon Brief provides in-depth analysis of all the key outcomes in Belém – both inside and outside the COP.

Brazilian leadership‘Global mutirão’AdaptationAmbition and 1.5CClimate finance‘Unilateral trade measures’Climate scienceJust transition work programmeLoss and damageGenderArticle 6Agriculture and food securityMitigation work programme

COP reformAround the COP Fossil-fuel roadmap‘Action agenda’DeforestationChina at COP30Global leadersCountry pledgesNew climate scienceFood systems and waterProtests and accessRoad to COP31 and beyond

(See Carbon Brief’s coverage of COP29, COP28, COP27, COP26, COP25, COP24, COP23, COP22, COP21 and COP20.)

Formal negotiations

Brazilian leadership

Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva first made his bid to host an “Amazon COP” at COP27 in Egypt in 2022, fresh from an election victory.

Speaking in front of a cheering crowd, he laid out a vision for reversing deforestation in Brazil and hosting a rainforest COP in 2025, telling delegates:

“I advocate in a very strong way that the conference should be held in the Amazon.”

Lula faced no challenges from other countries and, at COP28 in Dubai in 2023, it was formally confirmed that Brazil would host COP30, representing the Latin American and Caribbean Group (GRULAC).

Lula’s insistence that COP should take place in the Amazon left only a few viable host city options, including Manaus, the capital of Amazonas state, and Belém, capital of Pará state.

Though Manaus offered some advantages, such as having its own stadium built for the World Cup in 2014, Lula opted for Belém – with some suggesting the decision was linked to Pará state governor, Helder Barbadlho, being a key ally of Lula’s Workers’ party.

After Belém was chosen, concerns were immediately raised that the city would not have enough accommodation for COP30’s 56,000 registered delegates.

In February, Lula caused consternation when, according to Folha de São Paulo, he responded to the fears by saying:

“If you don’t have a four-star hotel, sleep in a three-star hotel. If you don’t have a three-star hotel, sleep [under the] stars in the sky, which will be wonderful…They have to know how much a carapanã [a common mosquito in the Amazon] bite hurts.”

Though rumours swirled that the conference would have to be relocated to Rio de Janeiro, preparations in Belém continued, with the number of available rooms increasing from 18,000 to 36,000 from January to May, according to Brasil de Fato.

In August, just three months before COP30, the Brazilian government launched the summit’s accommodation booking platform, following pressure to do so from a UN committee, Climate Home News reported.

Despite this, “markups and sky-high prices remained”, raising worries that delegates from developing countries would not be able to afford to access the talks, it added.

Just days before the talks began, the COP30 presidency attempted to address concerns by offering free cabins on cruise ships to delegates from African countries, small island states and the least-developed countries (LDCs) group, Reuters said.

The environmental credentials of Lula’s government also came under scrutiny in the run up to the talks.

In August, Lula signed into law what many called the “devastation bill” for its impact on Brazil’s environmental licensing structure, after it was approved by the nation’s largely opposition-led congress, Sumaúma reported.

Just weeks before the talks, Lula’s government approved new oil and gas drilling at the mouth of the Amazon river, drawing condemnation from environmental groups, Mongabay said.

Unusually for a COP, the two-day “high level segment” – where world leaders give speeches with their views and plans on climate change – took place before the summit’s official opening from 6-7 November.

The COP30 presidency said this was to allow more time to rally action – and to avoid the summit’s accommodation crisis.

Reflecting a difficult geopolitical situation heading into COP30, the leaders of China, the US and India – the “planet’s three biggest polluters” – were “notably absent” from the leaders summit, reported the Associated Press.

Lula used his speech at the event to call for “roadmaps” away from deforestation and fossil fuels – he later repeated this in his speech during COP30’s opening. (His call sparked a movement of countries to push for roadmaps in Belém. (See: Fossil-fuel roadmap and deforestation.)

André Corrêa do Lago – a Brazilian economist, diplomat and former climate negotiator – was appointed the president of COP30. (He is the first former negotiator to take up this position.)

André Corrêa do Lago, President-designate of the COP30 in Belém. Credit: Kay Nietfeld / Alamy Stock Photo.

Ahead of the opening plenary on the summit’s first day, his team managed to avoid a time-consuming “agenda fight” by telling parties that the presidency would hold consultations on four items some blocs had sought to add to the agenda. These “big four” were on trade measures, climate finance, ambitions to keep global warming to 1.5C and data transparency.

Corrêa do Lago said that the presidency consultations would be followed by a special “stocktaking plenary” on Wednesday, where it would be decided how to take the discussions forward.

Proceedings were disrupted on Tuesday evening, when dozens of Indigenous protesters forced their way into COP’s “blue zone”, leading to clashes with security staff who sustained minor injuries, Reuters said. The protesters were expressing anger at a lack of access to the negotiations, according to the newswire.

The breach prompted UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) executive secretary, Simon Stiell, to write to both the COP30 presidency and the Brazilian government, to raise concerns about the “wellbeing of delegates and personnel”, Bloomberg reported.

Along with security concerns, Stiell said that delegates had been facing dangerously high temperatures due to faulty air conditioning units, in addition to water leakages and flooding inside the venue, the publication said. The presidency responded by promising to resolve all issues as quickly as possible.

At a press conference on Wednesday afternoon in the first week, COP30 strategy director Túlio Andrade gave an update on the presidency consultations for the additional items on trade measures, climate finance, 1.5C and transparency.

He said that seven hours of consultations had been held and stated that parties had been working together in a manner not witnessed in a “long, long time”.

Alongside him, Corrêa do Lago promised that the stocktaking plenary, scheduled for later that day, would bring “good news” for all, and agreed that the consultations had been “super constructive”.

However, when the plenary began just a few hours later, it ended abruptly, with Corrêa do Lago announcing that more consultations were needed and that the meeting would be rescheduled for Saturday.

As days passed with few new updates, some delegates theorised that the additional items would most likely be taken forward by some kind of “cover text” – an overarching political document that COP presidencies can choose to introduce, to summarise key negotiated outcomes, along with issues not on the official agenda.

However, Corrêa do Lago refused to be drawn on the possibility of a cover text in daily press conferences.

He also largely batted away questions about whether the outcome would include a reference to a “fossil-fuel roadmap” – as called for by Lula and a growing number of developed and developing countries at the summit.

On Thursday, the presidency announced the ministerial pairs of developed and developing nations that would steer key topics in the second week of negotiations.

This included the UK and Kenya on finance, Norway and UAE on the “global stocktake”, Germany and Gambia on adaptation, Spain and Egypt on mitigation, as well as Poland and Mexico on just transition.

On Saturday evening, Corrêa do Lago held the stocktaking plenary session, where he said the presidency consultations had been “rich with ideas”.

The following night, he then published a five-page “summary note”, which listed various options for how the discussions could be taken forward.

One of the possible outcomes listed was a “mutirão decision”, widely interpreted as a possible overarching text containing the key agreements from COP30.

On Monday afternoon, Corrêa do Lago held a muddled press conference, where he floated the possibility of “two packages” coming out of the summit: a “political package” covering the “big four” themes in consultations and another on negotiated tracks, plus other items.

After Corrêa do Lago rushed out to resume meetings, COP30 CEO Ana Toni became the first in the presidency to make an open reference to a “cover text”.

The presidency later followed up with a letter clarifying its position that it was looking to pursue an overall “Belém political package”, rather than a cover text.

The letter added that the presidency hoped to “complete a significant part of our work by tomorrow [Tuesday] evening, so that a plenary to gavel the Belém political package may take place by the middle of the week”.

The idea of finding agreement on the summit’s key text several days before the COP was scheduled to finish was something that had never been achieved before at international climate talks.

In the end, an early deal failed to materialise.

‘Global mutirão’

COP30 saw countries agree to a new “global mutirão” decision, a text calling for a tripling of adaptation finance by 2035 (later than some hoped), a new “Belem mission” to increase collective actions to cut emissions and – to the disappoint of many countries – no new “roadmaps” on transitioning away from fossil fuels and reversing deforestation.

(See Carbon Brief’s snap analysis and further detail in: Adaptation; Ambition and 1.5C, “Unilateral trade measures”; Fossil-fuel roadmap; and Deforestation.)

The first draft “global mutirão” text appeared during the summit’s second week, in the early hours of Tuesday morning.

“Mutirão” is a Portuguese word originating in the Indigenous Tupi-Guarani language that refers to people working together towards a common aim with a community spirit – something the COP30 presidency was keen to emphasise.

The presidency was also keen to stress that the mutirão text was not a cover text (sometimes referred to as a “cover decision”). However, like a cover text, it sought to bring together important issues that were not on the formal agenda with negotiated targets, acting as the key agreement from COP30.

The first draft drew together the “big four” issues of finance, trade, transparency and ambition.

For most of the major elements, the first draft listed various options.

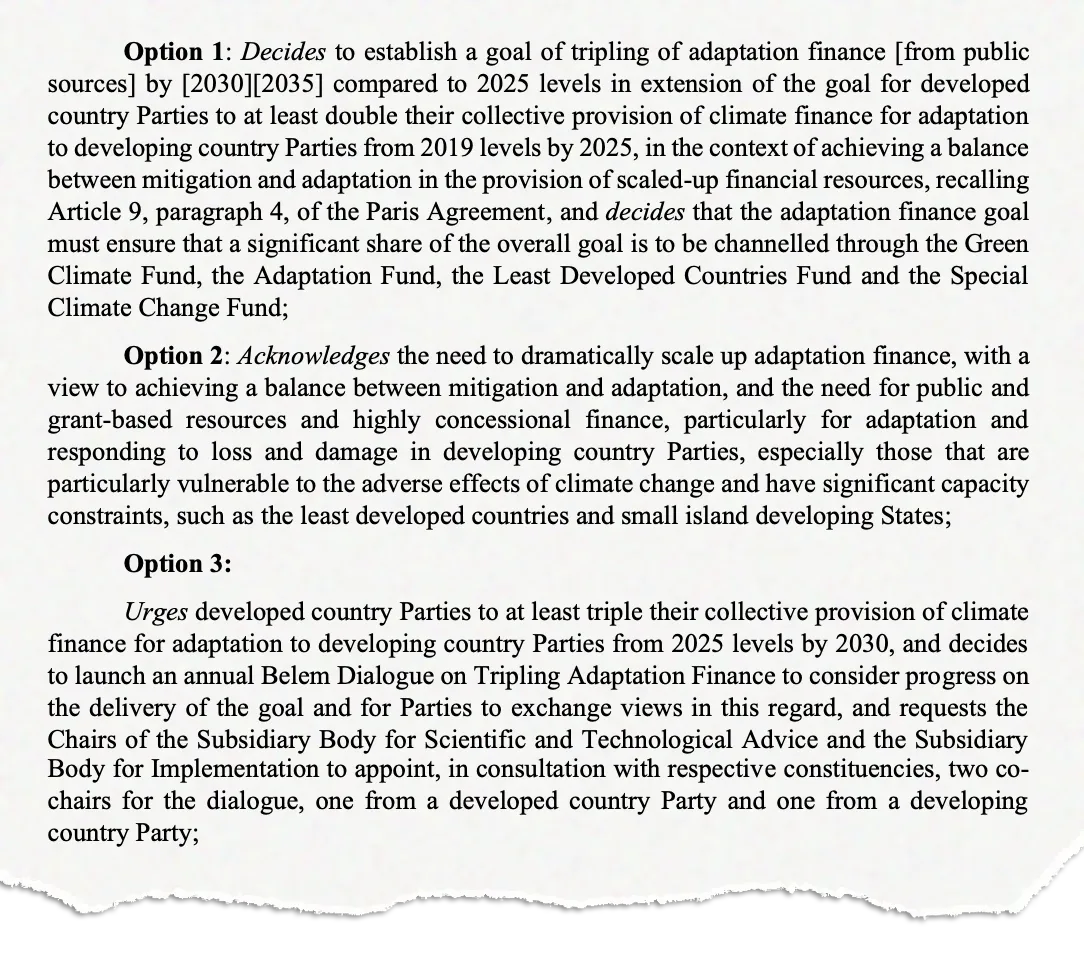

For example, paragraph 56 listed three different options for how developed countries might triple spending on adaptation finance, while paragraph 35 floated three options for a possible “roadmap” away from fossil fuels, including one that simply said “no text”.

The first draft drew immediate condemnation from a group of 82 nations that wanted to see a more ambitious and certain call for a fossil-fuel “roadmap” included in the mutirão.

However, COP30 CEO Ana Toni told a press conference attended by Carbon Brief later that day that a “great majority” of country groups they had consulted saw a fossil-fuel roadmap as a “red line”. (A list of such countries was never made public.)

Lula returned to Belém on Wednesday and – as hopes of an early deal evaporated – he spent his time conducting bilateral meetings with delegations from different negotiating groups with the hope of moving negotiations forward.

Despite negotiations running late into the night on Wednesday, no new mutirão texts emerged by Thursday.

At around 2pm on Thursday, a major fire broke out in the Africa pavilion inside the COP venue, with large orange flames engulfing the surrounding area and burning a hole through the roof. The fire sent delegates in the pavilions area running for the exits.

The COP30 presidency and UNFCCC put out a joint statement saying the fire was extinguished within six minutes, all delegates were evacuated safely and 13 people were treated for smoke inhalation.

Pará state governor Helder Barbalho told local news outlet G1 that a generator failure or a short circuit in the pavilion may have started the fire, NPR reported.

(Carbon Brief understands there was also a fire in the green zone in the first week of the summit, also caused by an electrical fault.)

The fire temporarily put the negotiations on pause, but they were able to resume after 8pm on Thursday night, organisers said.

Early on Friday morning, a long-awaited second version of the draft “mutirão” text emerged.

This text called “for efforts to triple adaptation finance” by 2030, a presidency-led “Belém mission to 1.5C” and a voluntary “implementation accelerator”, as well as a series of “dialogues” on trade.

It did not refer to a “fossil-fuel roadmap”, sparking condemnation from some countries and campaigners. (See: Fossil-fuel roadmap.)

With different countries still poles apart on key issues in the mutirão, negotiations dragged all through Friday.

At one point on Friday afternoon, talks had “descended into turmoil”, as the presidency tried to move discussions into three “huddles” on trade, adaptation finance and ambition, according to several observers speaking to Carbon Brief.

Many countries objected to the lack of a huddle on fossil fuels, while Saudi Arabia said the idea of targeting the energy sector was “off the table”, the observers told Carbon Brief.

After a break, talks resumed, with four huddles being formed, including one on fossil fuels.

During the night, as tensions were rising, UK special climate envoy Rachel Kyte posted on LinkedIn saying that “ministers and negotiators are clutched in huddles, trying to negotiate with each other as opposed to having everything mediated through the Brazilian presidency”.

Speaking to a group of journalists on Saturday morning, EU climate commissioner Wopke Hoekstra described it as a “difficult and intense evening”.

At 10am, the presidency sent an email to delegates saying a new text would soon be circulated and that a closing plenary would follow.

The final version of the mutirão text emerged, “calling for” a tripling of adaptation finance, but with no clear baseline year and a target date of 2035, five years later than an earlier draft. It also contained no fossil-fuel roadmap. (See: Adaptation.)

At a closing plenary, the text was adopted with no objections.

After brief applause, Corrêa do Lago acknowledged that some countries were hoping for “more ambitious” outcomes from the text.

He then announced that the COP30 presidency would bring forward two roadmaps, on transitioning away from fossil fuels and deforestation, to present at the next COP.

He added that the fossil-fuel roadmap will be guided by an upcoming conference on transitioning away from fossil fuels hosted by Colombia and the Netherlands in April.

Corrêa do Lago went on to rapidly gavel more of COP30’s key texts, including on the “global goal on adaptation” (GGA), and the just transition and mitigation work programmes.

However, Panama, supported by other Latin American countries and the EU, took to the floor in plenary to say its attempt to raise an intervention ahead of the GGA being gavelled was ignored by the Brazilian presidency.

Colombia also took the floor, to say that its attempt to raise a flag before the adoption of the mitigation work programme was also ignored.

The closing plenary was suspended for an hour to allow for further consultations between the presidency and parties unhappy with the adoption process.

After the plenary resumed, delegates spent another six hours gavelling through more texts, including on gender equality and a host of more technical items, in addition to hearing more statements from countries and observers.

According to Carbon Brief calculations, in total, there were more than 150 pages of decision text adopted across the various bodies meeting at the COP.

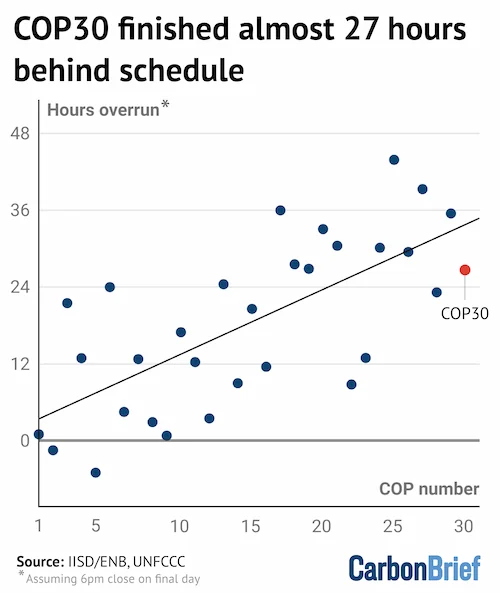

COP30 officially finished at 8:44pm on Saturday evening, making it only the 11th longest climate talks in history.

Chart and analysis by Joe Goodman for Carbon Brief

Adaptation

One of the biggest negotiated outcomes at COP30 concerned efforts to adapt to the impacts of climate change, with Corrêa do Lago dubbing it the “COP of adaptation”.

In particular, negotiators were expected to agree to a list of “indicators” that would allow countries to measure their progress under the global goal on adaptation (GGA). A much-reduced set of indicators was, ultimately, agreed at COP30.

However, calls for a new adaptation finance target quickly drew focus. The key “global mutirão” decision at the talks “calls on” countries to triple adaptation finance by 2035.

This followed a request from the LDCs at climate talks in Bonn earlier this year for a target to triple adaptation finance by 2030.

In 2021, a target to double adaptation finance to $40bn by 2025 was agreed at COP26 in Glasgow, UK.

However, a recent report from the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) found that, in 2023, developed nations provided just $26bn in adaptation finance to developing nations.

This marks a drop from $28bn in 2022 and is far short of the annual adaptation-finance needs for these nations, which UNEP puts at around $310bn annually out to 2035.

UNEP warned that, based on current trends, developed nations will miss the Glasgow goal.

A negotiation on a new adaptation-finance target for the years after 2025 was not included in the COP30 agenda. Over the course of the first week, a new goal was proposed in discussions on the GGA, national adaptation plans (NAPs) and the adaptation fund.

The LDCs’ proposal to triple finance to $120bn by 2030 was supported by small-island states (AOSIS), the African group, Grupo Sur and others.

It faced opposition, primarily from developed countries in the EU and the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG), the latter of whom noted that reference to such a target would be construed as an attempt to renegotiate the “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG).

Speaking during a press huddle, Aichetou Seck, an LDC adaptation negotiator from Senegal, said:

“We cannot keep returning to debate figures; the figures will only grow if action does not follow. What is needed now is a COP that elevates adaptation and sends a clear signal that adaptation finance is indispensable.”

With no official home, the question of a new adaptation-finance target was taken up within the presidency consultations. (See: Global mutirão.)

The first mutirão draft included a number of options, including one to “establish a goal” of developed countries tripling their provision of adaptation finance, with options for this to come exclusively “from public sources” and proposed deadlines of either 2030 or 2035.

There were also less ambitious proposals, merely “urging” a tripling of adaptation finance or “acknowledging” the need for a general increase in this finance.

Draft global mutirão published on 18 November. Source: UNFCCC.

Simultaneously, negotiations got underway on the GGA. Over the past two years, experts worked to turn a list of 10,000 potential indicators for tracking adaptation into just 100.

Cracks quickly emerged at COP30. Unity within the G77 and China coalition of developing countries fractured on the first day of negotiations, when the African group proposed a two-year “political refinement” process ahead of indicator adoption. Latin American countries called for adoption at COP30.

The African group argued that the indicators were “intrusive” and that African countries required more adaptation finance to take them on.

Richard Muyungi, African group chair, told Carbon Brief in the first week:

“We need to put guardrails or caveats on the adoption [of the indicators]. For example…the indicators should not infringe on the sovereignty of countries, asking countries to change their laws, their strategies. I mean, you cannot ask my country to change laws, because they want to address the global goal.”

Speaking during a press conference, Jacobo Ocharan, head of political strategies at Climate Action Network (CAN) International, noted that 48 of the indicators required support and finance in order to be actionable.

He asked: “What are you going to measure…in two years if that finance is not there?”

Other areas of disagreement within the GGA included opposing views on topics such as the Baku adaptation roadmap, the concept of “transformational adaptation” and language on “cross-cutting considerations”.

However, the key sticking point remained the indicators. Jeffrey Qi, policy advisor with IISD’s resilience program, told Carbon Brief that negotiators were trying to find a “tricky” balance. He said this included keeping indicators around domestic resource mobilisation that developed countries wanted, but which developing nations opposed.

The issue was complicated by the continued divide within the developing-country groups.

Speaking in a media huddle, Latin American ministers highlighted adaptation finance, but continued to emphasise the need to adopt the indicators. Edgardo Ortuño Silva, environment minister of Uruguay, said:

“We will not accept less in our conference than the adoption of action indicators and implementation means consistent with the [UNFCCC] and the Paris Agreement.”

Draft negotiation texts showed little progress in the second week, with the number of undecided, bracketed parts of the text doubling to nearly 100.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Bethan Laughlin, senior policy specialist at the Zoological Society of London, said that the “massive elephant in the room is the lack of adaptation finance”, but that a goal within the presidency text could “unlock a huge amount of it”.

As negotiations drew to a close a new text seemingly found a landing ground. It included an annex of 59 of the potential 100 indicators, emphasising that they “do not create new financial obligations or commitments”.

The text also contained plans for a two-year “Belém-Addis vision” to further refine the indicators.

The only remaining bracket within the text was a placeholder for the final adaptation finance target from the mutirão.

This text was released on the same day and included weakened language that merely “call[ed] for efforts” to triple adaptation finance compared to 2025 levels by 2030.

Ana Mulio Alvarez, researcher on adaptation at thinktank E3G, told Carbon Brief that the indicator compromise was “satisfactory”, as it allowed the framework to advance while including further refinement, but that some aspects remained “ambiguous”.

She added that a small group of negotiators had altered some of the indicators, “render[ing] some unusable, suggesting the list may need to be revised again”.

The final GGA text retained the adoption of the 59 indicators and the two-year programme “aimed at developing guidance for operationalising the Belém adaptation indicators”.

The GGA was gavelled through during the closing plenary, but met with a mixed response. While there was clapping in the room, Latin American countries, the EU, Canada and others voiced criticism and said they could not support the outcome.

Panama, for example, referred to it as a “rushed draft” and argued that this “is not how we reach a global goal on adaptation”. The statement was met with a round of applause.

Following a pause in the plenary, Corrêa do Lago requested further work on the GGA at the Bonn climate talks in June 2026.

The GGA text retained the placeholder for an adaptation-finance goal within the final mutirão text.

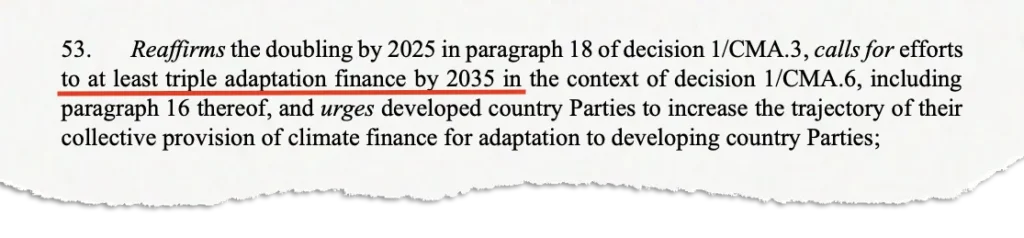

Ultimately, this “reaffirm[ed]” the doubling goal from Glasgow, “call[ed] for efforts” to triple adaptation finance and “urge[ed]” developed countries to increase the “trajectory” of their finance provisions, largely mirroring the previous draft.

Final section on adaptation finance in the mutirão text. Source: UNFCCC.

However, the deadline for the tripling target was pushed back by five years and the reference to 2025 as the baseline for this goal was removed.

Joe Thwaites, a senior advocate for international climate finance at NRDC, told Carbon Brief there was “ambiguity” in the goal, but added:

“The decision to triple was taken in 2025 and the old goal expires in 2025, so absent anything saying otherwise, that should be the assumption.”

Carbon Brief understands that, with no baseline officially in the text, the Standing Committee on Finance could provide a space where the baseline is defined by parties.

Beyond the GGA and adaptation finance, negotiations on NAPs followed on from tense sessions at COP29 and in Bonn, both of which ended without agreement.

According to Qi, within the NAP negotiations, “finance is the main issue…if you look at the text, it’s the same issue over and over again. So you just need to streamline everything.”

Ultimately, a decision was adopted in COP30’s closing plenary, marking an end to the stalemate in NAP negotiations.

[Content truncated due to length…]

From Carbon Brief via this RSS feed