A new series of articles published in The Lancet examines the influence of the ultra-processed food (UPF) industry on today’s food systems, identifying it as a central driver of an increasingly urgent public health crisis. Researchers and activists from around the world warn that despite strong scientific evidence on the harms of UPF-dominated diets – and despite the availability of policies that could address them – UPF producers and their allies continue to obstruct reform.

“We propose that the key driver of the global rise in UPFs is the growing economic and political power of the UPF industry, and its restructuring of food systems for profitability above all else – especially by the business practices of its leading corporations – in an increasingly financially-driven, capitalist world economy,” the authors of one article write.

Read more: Is corporate lobbying influencing US positions at the WHO?

Between 2009 and 2023, global UPF sales rose from USD 1.5 trillion to USD 1.9 trillion. This growth has benefited not only corporate giants headquartered in North America and Western Europe, such as Nestlé, Coca-Cola, and Mondelez, but also their suppliers, marketing firms, and affiliated researchers. The article notes that the industry’s model rests precisely on profit maximization. UPF manufacturers rely on cheap ingredients and industrial processing to keep production costs low compared with traditional and local food systems; this allows them to create food-like products using inexpensive compounds, while simultaneously driving consumption through aggressive advertising and the engineered palatability of these products.

“In capitalist economies,” the authors write, “where investments flow to the most profitable firms and industries, this drives the structural transformation of food systems in favor of ultra-processed diets.” This dynamic creates a vicious cycle where the UPF industry depletes food systems worldwide yet is rewarded financially, including through shareholder payouts. Between 1962 and 2021, the article suggests, more than half of the USD 2.9 trillion in shareholder payments linked to US food production came from the UPF sector, further boosting the industry’s appeal.

But internal profit logic is not the only factor behind the industry’s rise. Major UPF corporations – notably Nestlé, Coca-Cola, Unilever, PepsiCo, Danone, Mars, Mondelez, and Ferrero – have mirrored tactics long associated with the tobacco, alcohol, and fossil fuel industries. These include lobbying governments, shaping policy language and models, and hijacking public debate. This kind of political activity, the authors argue, “is the most important barrier to the implementation of effective public policies to reduce UPF-related harms.”

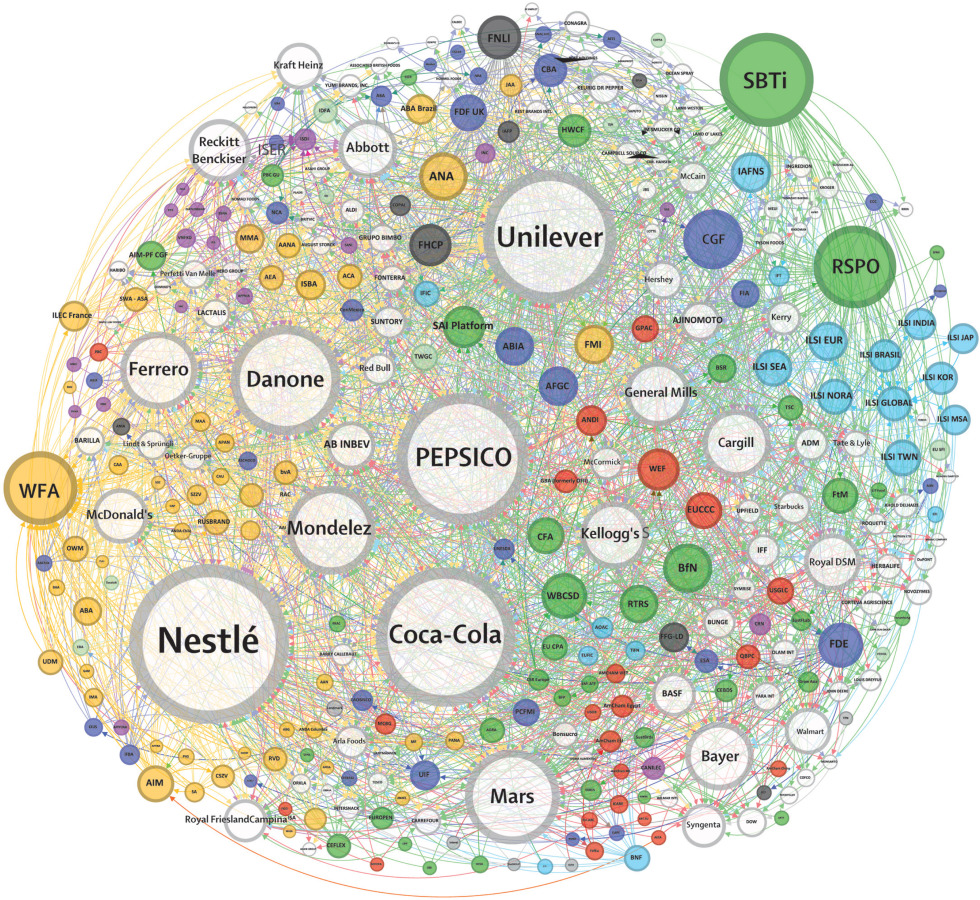

Circle size shows how many links each group has in the UPF industry network. Colors indicate different types of organizations: corporations, business associations, advertising groups, CSR and multi-stakeholder initiatives, food and beverage industry associations, infant nutrition groups, agribusiness organizations, and industry-funded science and consumer groups. Lines show declared memberships drawn from publicly available disclosures. Source: “Towards unified global action on ultra-processed foods: understanding commercial determinants, countering corporate power, and mobilizing a public health response”. Baker, Phillip et al. The Lancet, November 18, 2025

Crucially, these corporations do not operate in isolation. The articles series identifies around 200 interconnected interest groups, ranging from manufacturers’ associations to advertising and agroindustry lobby organizations, through which UPF producers organize their influence. Through this web of relations, the industry is able to impose its agenda, undermine progressive public health regulations, and sideline independent research.

Read more: Mexico raises the flag for health sovereignty

Just like in the case of other harmful industries, governments in the Global North remain deeply influenced by UPF actors, often advancing their priorities through institutions such as the World Trade Organization. Yet the articles insist that today offers an important opportunity to change course. Despite industry pushback, scientific understanding of UPF-associated harms is expanding, and some countries have already introduced meaningful regulations. “Successes in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa show that effectively regulating UPF production, marketing, and consumption is possible through multi-component policies, even in the face of strong industry resistance,” the authors note, citing progress in Mexico and Ghana, among others.

Still, they argue, fully transforming food systems requires far more coordinated action from policymakers, civil society, and activists, including broad coalitions capable of countering corporate pressure and advancing a just transformation of food systems. The series adds that such a transformation must be grounded in food sovereignty and adapted to local contexts, ensuring that workers currently employed in the UPF industry are not left behind. Potential policy solutions leading to this outcome, according to the articles, include stricter regulation of marketing, adequate taxes on actors profiting from UPF production and sales, but also – importantly – public investment in collective food provisioning such as school meal programs and community kitchens.

People’s Health Dispatch is a fortnightly bulletin published by the People’s Health Movement and Peoples Dispatch*. For more articles and to subscribe to People’s Health Dispatch, click* here.

The post Industry remains biggest barrier to tackling ultra-processed food harm appeared first on Peoples Dispatch.

From Peoples Dispatch via this RSS feed