Photographs by Elinor Carucci

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. somehow knew, even as a little boy, that fate can lead a person to terrible places. “I always had the feeling that we were all involved in some great crusade,” Kennedy once wrote, “that the world was a battleground for good and evil, and that our lives would be consumed in that conflict.” He was 9 years old when his uncle was assassinated and 14 when his father suffered the same fate. I happened to be sitting next to him this fall when he learned that his friend Charlie Kirk had been shot. We were on an Air National Guard C-40C Clipper en route from Chicago to Washington, D.C., and one of Kennedy’s advisers, her eyes filling with tears, whispered the news in his ear. “Oh my God,” he said.

National Guard stewards handed out reheated chicken quesadillas, which Kennedy declined in favor of the quart of plain, organic, grass-fed yogurt his body man had secured for him. A few weeks earlier, a man who believed that he’d been poisoned by a COVID vaccine had fired nearly 200 bullets at the CDC’s campus in Atlanta, hitting six buildings and killing a police officer. Kennedy, who as secretary of Health and Human Services oversees the CDC, had just told me that his security team recently circulated a memo warning him of threats to his own life. “It said the resentments against me had elevated ‘above the threshold of lethality,’ ” he said. Kennedy greeted the threat assessment with remarkable equanimity. He put down his spoon in order to finish his yogurt in gulps directly from the container.

In an atmosphere of rising distrust of U.S. institutions, where even once-untouchable bastions of expertise such as the scientific establishment had been badly weakened by the coronavirus pandemic, Kennedy had emerged as a Rorschach test—truth-telling crusader, or brain-wormed loon?—for how Americans understood the populist furies riling the country. I’d told him that I wanted to understand his journey from liberal Democrat and environmental activist to MAGA insider and Kennedy-family heretic, on the theory that by examining his odyssey, I might better understand what separates us and help narrow the political divide. He was sympathetic but skeptical. “Yeah, if you pull that off …,” he said, trailing off with a laugh.

Kennedy himself has done much to fuel the rising distrust. He views some of the world’s most celebrated scientific and political leaders as charlatans. He calls some of the experts who work under him at HHS “biostitutes,” because he considers their integrity for sale to the industries they regulate. He rejects much of the scientific consensus regarding vaccines, arguing that they have likely seeded the growing epidemic of chronic illnesses. During a Senate Finance Committee hearing just days before our flight from Chicago, Kennedy had called one U.S. senator a liar and another ridiculous. A bipartisan majority of the panel, including two Republican doctors, voiced concerns that vaccine policies he supported threatened the lives of American children. Kennedy argues that journalists like me are complicit, along with the public-health establishment, in hiding truth from the American people. The nation was tearing itself apart, and Kennedy had positioned himself at the seams.

“The whole medical establishment has huge stakes and equities that I’m now threatening,” he told me. “And I’m shocked President Trump lets me do it.”

A year earlier, Kirk, the founder of the conservative youth group Turning Point USA, had hosted an event with Kennedy the same day the candidate ended his quixotic presidential campaign and endorsed Donald Trump. JFK and RFK Sr. “are looking down right now and they are very, very proud,” Trump had said on the occasion. Now, as we flew over Ohio, no one knew if Kirk would live. At the front of the plane, aides to Attorney General Pam Bondi, who was also on board, were using the in-flight Wi-Fi to stream the gruesome videos of the shooting on social media. Kennedy’s adviser came back with a draft post for the secretary’s X account: “Praying for you, Charlie.”

“Say ‘We love you, Charlie.’ ” Kennedy instructed.

Three days later, Kennedy had just returned from a Saturday-morning 12-step meeting for addiction near his new house in Georgetown—a neighborhood that the extended Kennedy clan had long called home but that he now described as a “liberal enclave”—when he texted me saying that he wanted to continue our conversation about the country’s social breakdown.

A majority of the people in his recovery meeting, he said, “were probably horrified the first time I walked in, because, you know, they read The New York Times and they watch CNN, and so I’m kind of like a monster to them,” he said. “Over time, I became very welcome.”

This gave him hope that, outside the rooms of recovery, we could shrink our divisions. Parts of society, he said, are supposed to function independent of politics. Science is one of them. “The entire purpose of science is to search for existential truths,” he said. “It’s not subjective. It should be objective. I believe science is a place where you can find unity if you can get a conversation going.”

The problem is that the conversation had long since broken down. In 1900, the top three causes of death in the United States were pneumonia, tuberculosis, and diarrheal diseases, which collectively killed nearly 1 percent of the country every year. A staggering 30 percent of all deaths occurred in children younger than 5. By the end of the century, vaccinations, antibiotics, clean water, improved sewage treatment, and pest control had drastically reduced the lethality of infectious diseases. Today, young children account for less than 1 percent of U.S. deaths. Life expectancy has been extended by nearly 30 years. This is a monumental accomplishment, attributable to the efforts of scientists and lawmakers who tested hypotheses, built consensus to pass policies, and then corrected that consensus when new evidence arose.

But since about 2010, the long, steady increase in life expectancy has flatlined. Chronic illnesses such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and lung disease now top our mortality tables—affecting some 130 million Americans and accounting for 90 percent of our $4.9 trillion annual health-care expenditure. We are the world’s least healthy high-income nation, bombarded with prescription-drug ads and buffeted by a wellness industry of alternative fixes. A September poll by Navigator, a Democratic public-opinion firm, found that seven in 10 Americans are convinced that the health system “is designed so drug and insurance companies make more money when Americans are sick.”

Kennedy aims to channel the frustrations of that majority to remake public health. He arrived at this goal by way of his decades as a trial lawyer focused on contamination of the nation’s water by polluting corporations. In the latter part of his career, he has come to perceive a comparable contamination of American health by pharmaceutical and food companies. A central premise of Kennedy’s leadership at HHS is that modern science is infected with bias that costs lives—that the regulatory agencies have been captured by industry, that medical journals are corrupted by the need to turn a profit, that even respected organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics operate with a myopic groupthink that hurts kids.

Elinor Carucci for The Atlantic

For years, Kennedy was a gadfly outsider. The scientific establishment ignored him. Even now that he sits atop America’s health bureaucracy, Kennedy told me, public-health authorities—whose convictions, he said, are more akin to religion than science—will not engage with him. He blamed his opponents for dodging his arguments on vaccines. “Why for 15 years have they refused to have a conversation with me? I’ve been asking for 15 years for somebody to come up and debate me on this,” he told me. “Their reaction to that is ‘Oh, don’t debate him. He’s too crazy. You don’t want to give him a platform.’ ”

In 2017, Kennedy thought he’d finally gotten the audience that would allow him to make his case about vaccines. At Trump’s insistence, Kennedy and some allies, including Aaron Siri, a vaccine-safety litigator, came to the National Institutes of Health with a stack of 84 studies that they said supported their claims about the unrecognized dangers of vaccines.

“We tried to engage him. We were trying to debate him,” Joshua Gordon, the former director of the National Institute of Mental Health, told me. He and his colleagues attended the meeting to argue that existing studies demonstrated no connection between vaccines and conditions such as autism, and to explain why Kennedy’s papers “were suspect.” But, Gordon said, “Kennedy and Siri refused to engage.”

Kennedy and Siri insist that it was the doctors and scientists who refused to engage, and Siri has published emails showing that Gordon eventually ended the conversation by referring them to the CDC. The meeting solidified Kennedy’s conviction that he was dealing with a cult unwilling to look at evidence that challenged its worldview.

Today, a similar pattern is playing out between Kennedy and his own staff. In late August, Kennedy asked that Trump fire Kennedy’s handpicked CDC director, just four weeks after she’d been confirmed by the Senate, because Kennedy was convinced that she was aligning herself with her agency’s scientific staff and against him. He replaced the members of the CDC’s vaccine advisory committee because he’d concluded that their COVID-era decision making had been unscientific and industry-influenced. His team uses social media to attack science reporters by name.

Even some members of Kennedy’s newly adopted party are alarmed. Last February, Senator Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, a gastroenterologist and the Republican chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, cast the deciding vote to confirm Kennedy as HHS secretary. A liver specialist, Cassidy has treated patients with cirrhosis caused by having been born with hepatitis B, a condition that can be avoided with newborn vaccination. Though Cassidy has thus far declined to renounce his endorsement of Kennedy, he rejects the secretary’s suggestion that the hepatitis vaccine might be dangerous when given to newborns.

“I’ve invited Bill Cassidy and others to sit down with me and go through the studies and let’s figure out which ones are right,” Kennedy told me. “That has to happen through real debate and conversation, and there’s no real place to have that in the current political milieu.”

When I conveyed Kennedy’s frustrations to Cassidy, the senator said that he and the HHS secretary regularly share scientific articles and papers with each other. “I find that he often will send me the same article more than once,” Cassidy told me. Yet whenever Cassidy points out “statistical flaws” in the article, he said, Kennedy says he considers those “immaterial.”

I had been having a similar experience. As I reported this article, Kennedy referred me to many studies meant to convince me there are not two valid sides to this debate, that his is the only valid one. I’m not a scientist. I’ve admittedly been inconsistent in getting my yearly COVID and flu boosters, confused about their benefits. Now the most powerful public-health official in the U.S. was asking me, a political reporter, to referee a medical debate with life-and-death stakes.

I called Paul Offit, a pediatrician and the director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and one of the most outspoken critics of Kennedy’s vaccine views. Offit helped invent a rotavirus vaccine that has mitigated a major cause of early-childhood hospitalization around the world. Kennedy routinely attacks him as a paragon of financial conflict because the owners of the vaccine patent, including his hospital, gave him some of the proceeds from its sale. The accusation relies entirely on circumstantial evidence: Offit’s early rotavirus research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, not private industry; he advocates for vaccination and sells books about the benefits of vaccines, but nothing suggests that he has ever done anything untoward in pursuit of profit. Like many of the people I spoke with for this article, Offit has faced death threats from radicals who believe his vaccine advocacy is deadly. Some have targeted his children.

Offit told me that Kennedy is a “liar” and a “terrible human being.” I asked him to explain. “It doesn’t matter what I say,” Offit said. “He thinks the medical journals are in the pocket of the industry, he thinks that the government is in the pocket of the industry, he thinks I’m in the pocket of industry, and he’s wrong.” Offit continued: “If he has data showing he’s right, then fucking publish it. He can’t, because he doesn’t have those data.”

I asked Offit if he saw a way to reverse the public’s rising distrust in science. “I don’t think there is any way to regain that trust other than have the viruses do the education, and the bacteria do the education, and then people will realize they paid way too high a cost,” he said.

From 2011 to 2024, the percentage of kindergarten students whose families asked for nonmedical exemptions to vaccine mandates doubled, to more than 3 percent, according to the CDC. Florida just announced an end to school vaccine mandates, and Idaho passed a law banning them. Cassidy’s office has been monitoring rising rates of pertussis, a bacterial infection also known as whooping cough; symptomatic infection is avoidable with a vaccine. Cassidy’s working hypothesis is that declining vaccination rates in red states will show up in the data. Kennedy counters that existing data are not specific enough to show whether the new infections are among the unvaccinated.

I first interviewed Kennedy for this story in June, in his office on the sixth floor of HHS headquarters, a brutalist gray block of concrete that resembles a giant air-conditioning unit. Kennedy’s staff jokes that the building feels like a prison; the secretary pointed out the great view he would have of the U.S. Capitol’s dome, if not for the building’s deep-set windows.

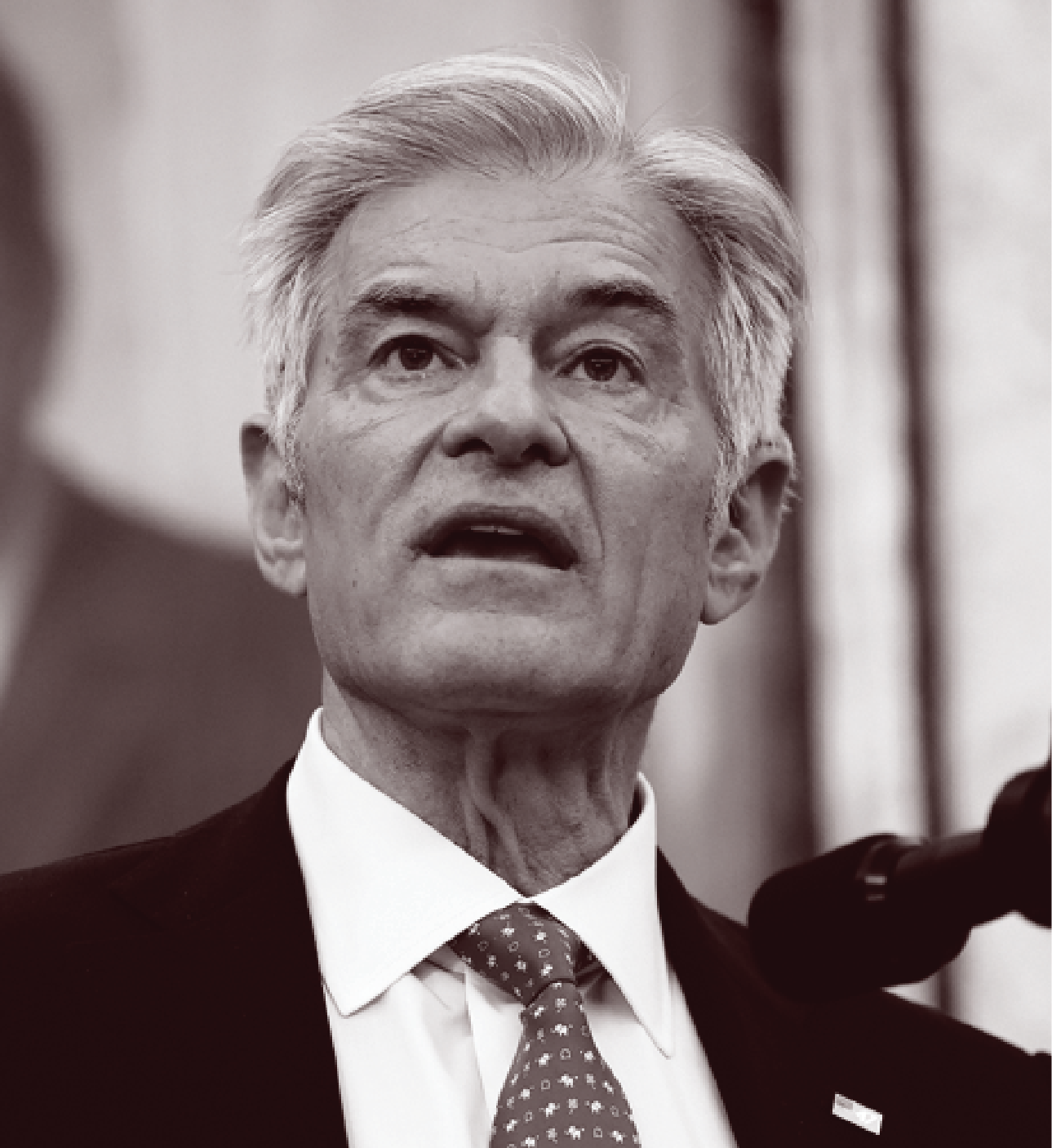

Kennedy is 71, but with the help of weight lifting, artificial tanning, a careful diet, and testosterone-replacement therapy, he looks more like a comic-book character than a senior citizen, his bronzed face all chiseled angles, his eyes sky blue. He adheres to a strict uniform at work—dark, embroidered skinny ties like his father sometimes wore, with suit jackets that bulge over his bodybuilder’s chest and biceps. He regularly pulls Zyn nicotine pouches from his shirt pocket or desk drawers to tuck between his lower lip and gum. When I asked him to square his nicotine habit and the time he spends tanning with the federal health advisories against both, he shifted in his chair. “I’m not telling people that they should do anything that I do,” he said. “I just say ‘Get in shape.’ ”

Kennedy told me his staff believed that speaking with me was a mistake. For the first half century of his life, national magazines hailed him as a public servant, a potential heir to the Kennedy kingdom—even, as Time magazine put it in 1999, a “Hero for the Planet.” “The Kennedy Who Matters,” New York magazine declared in 1995, saluting RFK Jr.’s environmental advocacy. In 2006, Vanity Fair posed him on the cover of its “green issue” with George Clooney and Julia Roberts.

But the favorable coverage dried up about 20 years ago, when he began arguing that mercury additives in vaccines were likely causing an epidemic of autism. This claim was contradicted even at the time by epidemiological studies by the CDC and others. Editors who did not want to discourage lifesaving vaccination stopped running flattering articles and started running critical ones. “All-out hit pieces,” he told me, “every one of them—like, ugly, hateful stuff.” For 20 years now, he said, only “bad articles” have been written about him.

Yet in the aftermath of COVID, his popularity has surged. Like Trump, Kennedy has drafted on the currents of populist backlash against expert authority. “When I’m on the street, I get stopped three times a block by people saying that they love me,” he said. Kennedy is among the most popular members of Trump’s Cabinet, according to an August Gallup survey: 42 percent of the country holds a favorable view of him, on par with the president himself. The public attacks on Kennedy’s character and integrity bother him, naturally, but he wanted me to know that I was not a threat. “If he screws us on this,” he recounted telling his staff, “it’s just another shitty article in a liberal paper, which doesn’t really hurt me.”

He believed that I’d screwed him before, anyway. I’d first met him in the spring of 2023, when he was challenging President Joe Biden for the Democratic Party’s nomination. The Washington Post story I wrote focused on his argument that the powerful were lying to the American people—about vaccines, environmental threats, the assassinations of his father and uncle, and much else. He hated the story largely because I’d used the word conspiratorial in the headline, which he argued was an elitist epithet for tinfoil hat. I placed him in the tradition of what the political scientist Richard Hofstadter described as America’s paranoid style, while acknowledging that secret conspiracies of the powerful—tobacco companies, the intelligence community—sometimes do exist.

He responded by sending me an email nearly twice the length of my original article, with 78 footnotes. (At the time, he was suing the Post for its role in a consortium designed to combat misinformation online.) “Your reporting on me reflects, exquisitely, the overt aspirations by your employer and its co-conspirators to crush nonconformist viewpoints in order to secure their own economic self-interests,” he wrote. Weeks later, on a podcast, he accused me of being “part of a conspiracy, a true conspiracy.”

I had never received an email like that from a politician. If I was hopelessly corrupt, why spend hours writing a response? It struck me that Kennedy believed himself to be on a ferocious quest. “There is nothing that is a show about what you are seeing,” Mike Papantonio, a former legal partner of Kennedy’s who co-hosted a program with him on the liberal radio network Air America in the mid-aughts, told me. “That is real rage.”

Kennedy and I stayed in touch. In October 2023, getting little traction from Democratic-primary voters, he relaunched his presidential campaign as an independent. Despite not having a clear path to even a single electoral vote, he didn’t stop until August 2024, when he endorsed Trump, a man he had weeks earlier publicly described as appealing to “some of the darkest impulses in the national psyche.”

As we talked more recently in his wood-paneled HHS office, he leaned back in his chair behind an oversize desk, with one of his five book-length attacks on the federal medical establishment, The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health, displayed nearby. From that seat, he oversees one out of every four dollars in the federal budget and regulates about 17 percent of the nation’s economy. How, I asked him, did he explain going from scorned activist to the boss of the public-health apparatus?

“I would say in one word: providential,” Kennedy said.

If I were to do this story right, Kennedy told me, I needed to talk with his top deputies: Jay Bhattacharya, the director of the NIH; Marty Makary, the commissioner of the FDA; and Mehmet Oz, the cardiothoracic surgeon turned TV doctor known for having hyped dubious “miracle” cures, who is now running the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. All three of these physicians, like Kennedy, say that they were transformed by the pandemic, which they thought public-health authorities had mishandled. They had dissented from government edicts regarding vaccine mandates and masking. Although they do not embrace all of Kennedy’s views on vaccines, his deputies share his big-picture view that America’s public-health system is broken.

Early in the pandemic, Bhattacharya, a Stanford University physician and health economist, co-wrote the 2020 “Great Barrington Declaration,” a document that argued against universal COVID lockdowns in favor of allowing healthy people to gather while isolating only those groups at greatest risk of severe illness or death, such as the elderly and the infirm. For this, Bhattacharya was ostracized by colleagues at Stanford and the broader scientific community: An email that later became public shows Francis Collins, then the NIH director, telling colleagues that they needed a “quick and devastating published take down” of the declaration. (Tens of thousands of Americans a month were dying from COVID at that time; overstrained hospitals were at risk of collapse.) Death threats—a recurring feature of public-health work these days—followed for Bhattacharya, who now compares the COVID years to pre-Enlightenment Europe, when Galileo Galilei was imprisoned by Catholic leaders for arguing that the Earth orbited the sun.

“What you had is a relatively small number of scientists who could decide what is true or false for all of science and all of society,” Bhattacharya told me. Today, even some of those who led the public-health response during those years admit that COVID-vaccine mandates may have been counterproductive, that social distancing lasted too long, and that masking may not have done much to limit transmission—though it is also true that we cannot know now how much higher the death rate would have been without those measures in place.

The COVID vaccines led to a substantial reduction in hospitalization and death from the disease, according to peer-reviewed studies. But Kennedy likes to emphasize that, as the virus evolved, the vaccines failed to prevent infection, as scientific authorities had initially suggested they would. Kennedy also dismisses the mathematical modeling of the lives saved, and says CDC estimates of the COVID death toll were inflated by “data chaos” in the government. What no one doubts is that the severity of the pandemic—more than 95,000 Americans were reported dead in one month at its height—has transformed the nation’s relationship with medical authority. From 2020 to 2022, public confidence in the CDC dropped from 82 to 56 percent, according to a study by researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The country has still not recovered.

Jim Watson / Getty

Bill Clark / Getty

Kevin Dietsch / Getty

Kennedy’s deputies: Jay Bhattacharya, the NIH director; Marty Makary, the FDA commissioner; and Mehmet Oz, who oversees Medicare and Medicaid

Kennedy’s team blames its Biden-era government predecessors. When I met with Makary, who worked as a pancreatic surgeon before being named FDA commissioner, he said that, in times of uncertainty, a dangerous and self-defeating “groupthink” can take over. Kennedy and his allies point to how public-health authorities urged social-media platforms to curb the posting of COVID misinformation, stifling debate. Kennedy himself got kicked off Instagram. In one social-media post, he called the death of the baseball great Hank Aaron at age 86 “part of a wave of suspicious deaths among elderly closely following” COVID-vaccine shots. Critics accused Kennedy of speculating baselessly about Aaron’s cause of death, and quoted the medical examiner’s office saying Aaron had died of natural causes. Kennedy, in turn, accused his critics of ruling out a vaccine connection without a proper autopsy, and demanded that one be done.

The COVID experience bonded Kennedy, Makary, Bhattacharya, and Oz in a fellowship of the ostracized. “We became renegades, personae non gratae, because we asked questions which you would think, certainly within academic medicine, you should be able to ask,” Oz told me in his office, where he keeps a taxidermic honey badger to symbolize fearlessness and aggression.

After Trump’s reelection, Kennedy’s HHS-leadership-team-in-waiting gathered at Oz’s 10-bedroom, 18,559-square-foot Palm Beach house, not far from Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate. The house was built by the same architect who built the mansion down the beach where Kennedy had spent vacations during his childhood. “It has the same smell to it,” he said. In the mornings, Kennedy would call on anyone who was around to go swimming in the ocean or throw a football with him, before his team settled down to plan the future of U.S. medicine. Kennedy’s friend Russell Brand—a comedian, an actor, and a fellow recovering addict who has pleaded not guilty to rape and sexual-assault charges in England—would sometimes join them. Kennedy says that those months in Palm Beach validated his decision to walk further away from the Democratic Party and most of his own family, who remained prominent Trump opponents. The Republicans hanging around Oz’s house, Kennedy told me, “were all very idealistic people, which was not my view of the Republican Party growing up. To me the most breathtaking and refreshing part of being down there is that people were not sitting in rooms, as the Democrats imagine, thinking, How do we cut taxes for rich people and screw the poor? They were saying, ‘How do you make every American better?’ ”

At one point, leaders of Stanford visited, only to be grilled by Kennedy and Oz about why the university had opened an investigation into Bhattacharya’s professional conduct during the pandemic. The outcasts had become the authorities.

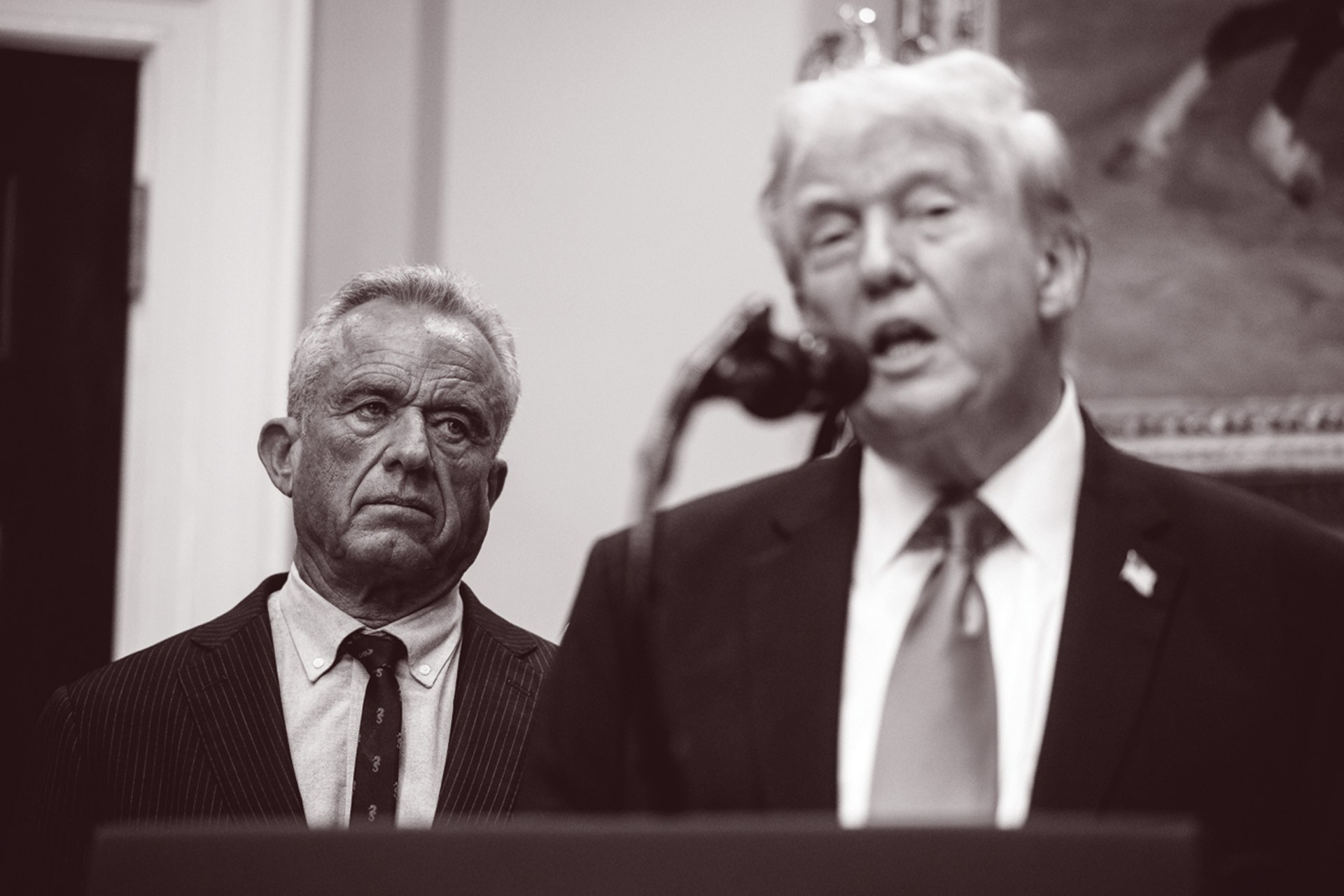

Kennedy now compares his relationship with the president to “when you’re dating somebody that you keep liking more and more.” They began meeting after the failed assassination attempt on Trump in July 2024. Kennedy came to believe that his previous impressions of Trump—that he was a “bombastic narcissist” who lacked curiosity and didn’t read books—had been wrong. “One day he sat on the plane with me. We were talking about Syria, and he drew a map of the Mideast for me. And it was a perfect map,” Kennedy told me. “Then he drew in the troop strength of each country, and also the troop strength on various borders.” Trump would recite sports trivia to Kennedy, and recount the net worth of major Wall Street financiers.

“I had to start seeing Trump as a populist who is standing up to really entrenched power and the deep state and that merger of state and corporate power,” Kennedy told me. He acknowledges that this makes Trump a strange “paradox”—“because he’s the most business-friendly guy at least since George W. Bush.”

That’s saying something coming from Kennedy, who in the early 2000s compared Bush’s pro-corporate environmental policies to the work of European fascists. I asked how he reconciled his criticism of Bush with working in the Cabinet of a president who appointed an oil executive, Chris Wright—who recently called Al Gore’s climate-change warnings “nonsense”—as energy secretary. “Chris Wright has a diverse worldview,” Kennedy told me.

For decades, RFK Jr. continued to call himself an “FDR/Kennedy liberal.” The embrace of MAGA has lost Kennedy friends and strained his family. At a rally against vaccine mandates in 2022, Kennedy described the U.S. COVID response as totalitarian, and warned that new technologies would give the government greater power to control Americans than the Nazis had over Anne Frank in Europe. In response, his sister Kerry Kennedy posted on X, “Bobby’s lies and fear-mongering yesterday were both sickening and destructive.” When RFK Jr.’s own wife, Cheryl Hines, famous for playing Larry David’s wife on the HBO show Curb Your Enthusiasm, publicly criticized him for those remarks, he apologized. Kennedy and Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democratic senator from Rhode Island, were once such close friends that they were in each other’s weddings. Now, when Whitehouse questions Kennedy at public hearings, his voice drips with disdain. “You have my cellphone,” Kennedy told his former friend during their last Finance Committee confrontation, in September. “I’ve never heard from you in seven months. Call me up. I’d love to meet with you.” (Kennedy says Whitehouse replied to his offer in late October and said he would meet, after Whitehouse’s Senate office had declined a request for comment from The Atlantic.) More recently, his cousin Tatiana Schlossberg, one of JFK’s granddaughters, who has terminal cancer, wrote in The New Yorker that she “watched from my hospital bed as Bobby, in the face of logic and common sense,” became HHS secretary, and admonished him for cutting cancer-research funding. (Kennedy declined to comment.)

“To stay on course despite that jeering really tells you a lot about his messianic self-regard,” the New York Democratic politician Mark Green, another former friend of Kennedy’s, told me recently. “He is sadly off his rocker to argue that Biden was more anti-speech and fascist than Donald Trump.”

Over time, Kennedy and his team united around an organizing theory of their department. “It’s a $1.73 trillion bundle of perverse incentives,” he told me. “The doctors, the hospitals, the insurance companies, the other providers, the pharmaceutical companies are all incentivized to make money by keeping people sick.” Fixing this would require radical measures.

The ensuing year has been a whirlwind of controversy, destruction, and new initiatives. Kennedy and the Trump White House pushed out, through firings and induced retirements, about one in four HHS employees, including much of the senior career staff and thousands of workers at the CDC, which Kennedy described to me as a “snake pit.” Early on, working with Elon Musk’s team at the Department of Government Efficiency, Kennedy canceled hundreds of millions of dollars in research grants, and defended a White House budget proposal that cut 40 percent of the NIH’s funding, even while saying that he would accept more money if Congress decided differently. “I talked to Elon a lot about this,” Kennedy told me. “You have to do something disruptive at the beginning.” If you don’t, “you lose momentum.”

On May 27, he shook scientists at the CDC by announcing that his department would no longer recommend COVID boosters for healthy children or pregnant women, on the grounds that clinical trials had not sufficiently demonstrated safety and efficacy for those populations. The career staff was outraged; Kennedy presented no new data on potential harm that would have compelled rescinding the existing recommendation, and it is well established that COVID infection increases the danger to both mother and fetus. “I knew that those decisions were going to harm people,” Lakshmi Panagiotakopoulos, a top adviser on COVID vaccines for the CDC, who resigned in response to Kennedy’s new policy, told me. “From my perspective as a scientist and someone who has done this her entire career, he has a lot of blood on his hands.”

Days later, Kennedy removed the 17 members of the CDC committee responsible for recommending vaccination schedules and replaced them with a smaller group that promptly ordered the removal of a mercury preservative, thimerosal, from flu vaccines, even though the CDC continues to describe thimerosal as “very safe.” Kennedy’s new committee put up barriers against a single shot to vaccinate children for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella, citing past studies by Merck and the CDC that found a higher incidence of febrile seizures following the combined vaccine. Kennedy also canceled $500 million in federal grants for mRNA-vaccine research, citing his conclusions, disputed by medical associations, that the technology performs poorly against fast-mutating respiratory viruses.

In other areas, he’s pushed for changes that health activists and wellness influencers on the left, as well as many in the scientific mainstream, have long sought. He launched initiatives to review baby-formula ingredients, issue new guidelines for fluoride use, limit student cellphone use, stop the sale of illegal flavored vapes, and remove restrictions on whole-milk sales at schools, and he persuaded governors in 12 states to ban the use of food stamps to buy sugary sodas. He announced plans to explore limits on direct pharmaceutical advertising and the marketing of unhealthy food to children, increase nutrition education for doctors, reduce prices on some drugs, add front-of-package labeling on ultra-processed foods, and require more testing of food additives. Under pressure from Kennedy’s HHS, major food producers announced that they would remove certain petroleum-based food dyes from cereals and candy.

Kennedy’s deputies describe him as endlessly curious about new science, and willing to listen to dissenting views. Bhattacharya told me that, during the 2025 measles outbreak in Texas, the worst in decades in the U.S., he privately advised Kennedy to endorse the measles vaccine as the most effective way to prevent the disease. “When you give him the evidence, he changes his mind along the lines of what the evidence says,” Bhattacharya said. Kennedy did go on to call the measles vaccine effective—while also emphasizing that parents should make their own decisions and promoting disputed treatments such as cod-liver oil for measles symptoms.

Bloomberg / GettyKennedy and President Donald Trump in the Roosevelt Room of the White House on September 22, 2025, when the president urged pregnant women not to take Tylenol, enraging the medical community

The secretary also consumes scientific studies by the bushel. In August, Andrea Baccarelli, the dean of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, published a review of the existing science suggesting a possible connection between taking Tylenol during pregnancy and the development of autism or attention deficit disorder in children. Kennedy told me he spent a weekend reading 70 studies related to this. He spoke with Baccarelli, started texting directly with another researcher on the topic, and asked the CEO of Kenvue, the company that now owns the Tylenol brand, to bring scientists to HHS to brief him.

Kennedy arrived at a rather nuanced set of conclusions—more nuanced than what his boss would subsequently express. High fevers in pregnant women are known to cause bad outcomes in newborns. So any public-health advice recommending against Tylenol, which reduces fevers, would have to be carefully weighed, he told me. But when he briefed Trump on his findings, Kennedy said, the president’s response was to suggest immediately posting a Tylenol warning on social media.

“You can’t do that,” Kennedy said he told the president. “There’s nuance to it, and you can’t scare people away from Tylenol, and you’re going to get a huge amount of pushback from powerful pharmaceutical companies.” Trump’s reply: “I don’t give a shit about that.” The FDA-advisory note that Marty Makary released to accompany the announcement weeks later asked doctors to exercise caution in using the medication for low-grade fevers but said that there was as yet no proof of a causal link between Tylenol and developmental disorders.

Trump, however, has less patience for nuance. “Don’t take Tylenol. Don’t take it,” the president said at a press conference on September 22. “Fight like hell not to take it.” The medical community responded with outrage. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and other prominent health organizations put out statements advising doctors and patients to disregard Trump’s recommendation.

Through all this, Kennedy has praised the president’s fearlessness and compassion. A few months earlier, at a White House event, RFK Jr. compared Trump to President Kennedy, who had worked with the biologist Rachel Carson in the early 1960s to reduce the use of pesticides. “My uncle tried to do this, but he was killed and it never got done,” Kennedy said, sitting alongside Trump. “And ever since then, we’ve been waiting for a president who would stand up and speak on behalf of the health of the American people.”

In a family steeped in its own mythology, RFK Jr. was always particularly susceptible to the pathos and grandeur of the Camelot mystique. His father encouraged him to read heroic poems like Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “Ulysses*,*” and as a child Bobby Jr. memorized Rudyard Kipling’s “If—” and “Gunga Din.”

The legend of King Arthur resonated with a boy who was more interested in catching salamanders and snakes in the forest than in schoolwork. T. H. White’s novel The Once and Future King, which tells the story of young Arthur’s tutelage under Merlyn, was a particular favorite. “That was how I got interested in falconry,” Kennedy told me. When he was 11, his father gave him his first red-tailed hawk. Kennedy named the bird Morgan le Fay, after Arthur’s sorcerer half sister.

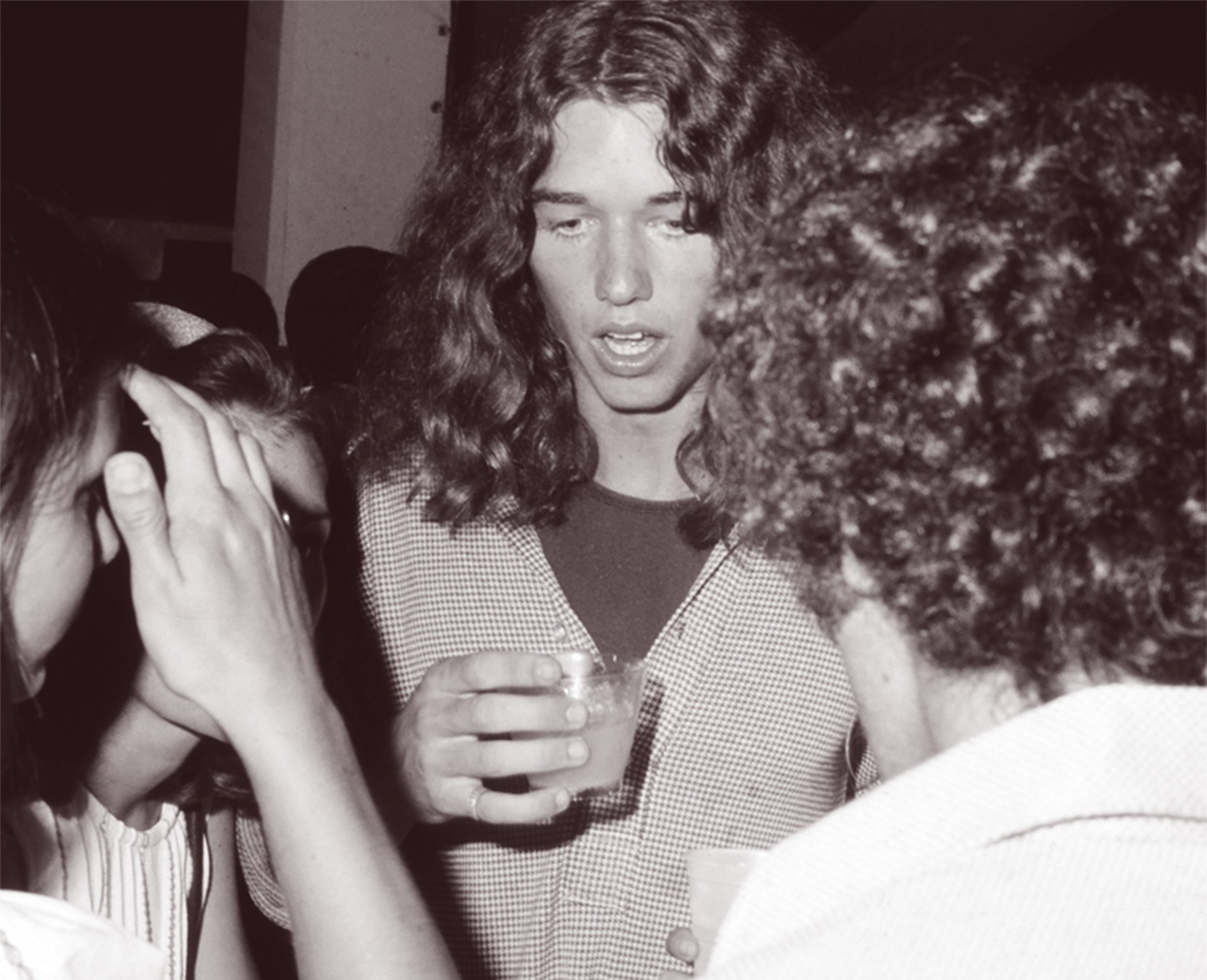

Associated PressRobert F. Kennedy, campaigning for president in 1968, three months before he was assassinated

But when his father was murdered, Ethel Kennedy, Bobby Jr.’s mother, was left to care for 11 children in a world churning with youthful rebellion. One day in the summer of 1969, Kennedy remembers, he attended a farewell party on Cape Cod for a young soldier heading off to Vietnam. He said LSD had arrived from California that summer, and while he was hitchhiking home that night, someone offered him a dose. His favorite comic book at the time, Turok, Son of Stone, followed the exploits of Native Americans who lived among prehistoric animals. In one of the comic’s storylines, the Native Americans consume a hallucinogenic fruit. “Will I see dinosaurs?” Kennedy told me he asked the person offering him the LSD. “I had a deep interest in paleontology,” he explained to me. That was perhaps the first time this particular reason has ever been given for deciding to take psychedelics.

A picture of his dead father and uncle behind the counter of a local diner as the drug wore off spoiled his trip. At which point another group of kids offered him a line of crystal meth. The initial rush was strong enough to set him on a new life path. Within months, he was traveling to New York City to buy $2 heroin on 72nd Street. “I had been administering drugs and giving shots to animals since I was a kid. And so it wasn’t a hard jump for me,” he said, about using needles to inject himself with drugs. “There were other kids in my town who were shooting speed.” He was 15.

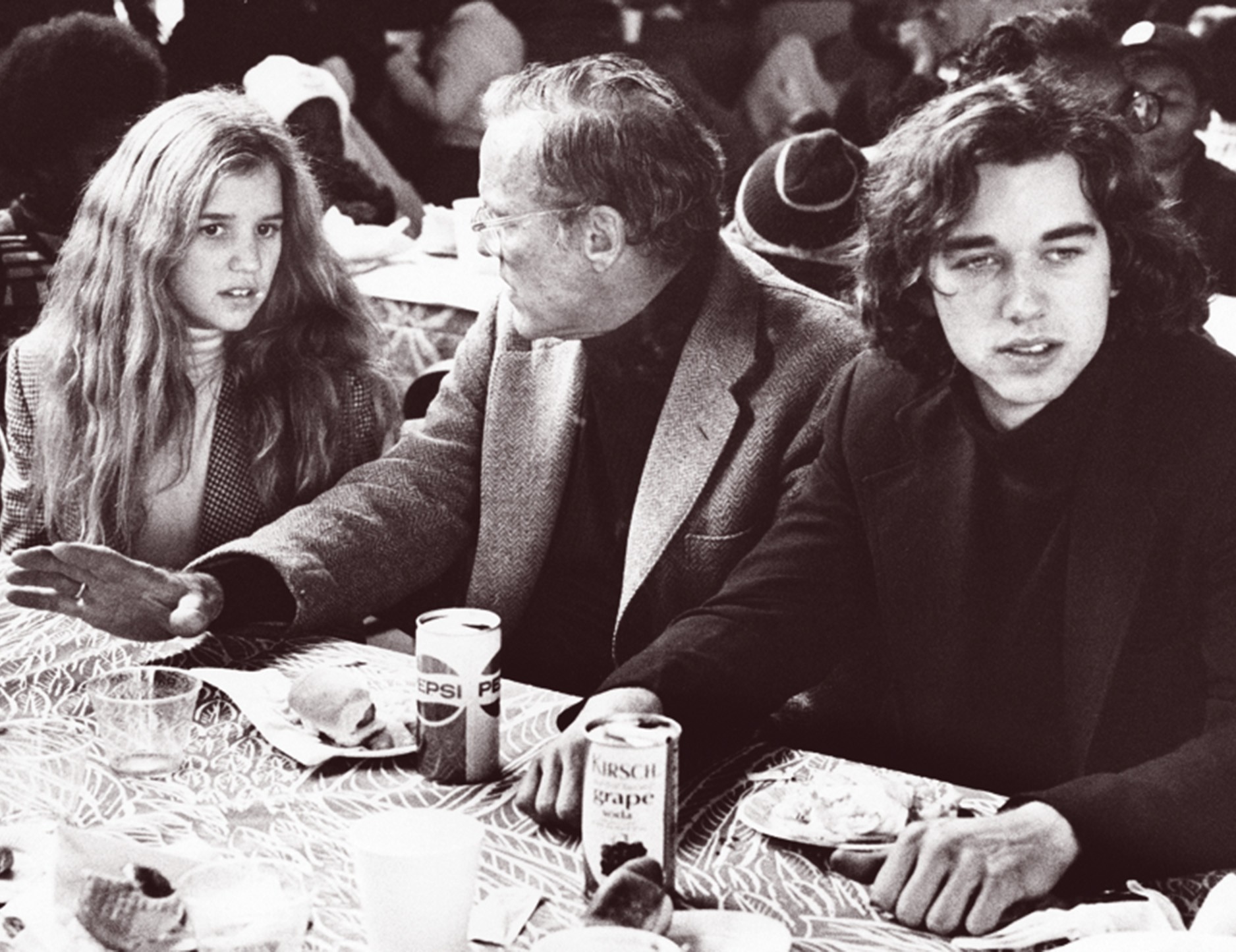

In January 2025, after Trump announced that he would be nominating Kennedy as HHS secretary, his cousin Caroline Kennedy, JFK’s daughter, wrote a public letter opposing his confirmation, in part because of what she’d witnessed during his years as a young drug user; she blamed him for leading others in the family “down the path of addiction.” She described young Bobby as a “predator” like the raptors he’d raised, saying he had grown “addicted to attention and power.” “His basement, his garage, and his dorm room were the centers of the action where drugs were available, and he enjoyed showing off how he put baby chickens and mice in the blender to feed his hawks,” she wrote. “It was often a perverse scene of despair and violence.”

When I read Kennedy those words, he barely reacted. “I would not contest it that much,” he said. “Addiction is kind of narcissistic.”

By the time he was accepted into Harvard (his father, his uncles, and his grandfather had all gone there), he had been pushed out of multiple boarding schools, been arrested for marijuana possession, and become estranged from his mother. When he was still a teenager, he hopped trains to Haight-Ashbury, in San Francisco, to hang with the hippies, and worked in a Colorado lumber camp. His heroin addiction would last 14 years, continuing during his time as a law student at the University of Virginia, as well as through his first marriage, to Emily Black, a fellow UVA law student, whom he married in 1982. In September 1983, he overdosed on a flight to South Dakota. He was charged with heroin possession, for which he was sentenced to two years’ probation, and spent the next five months in a rehab facility in New Jersey. Shortly after he left treatment, his brother David Kennedy, younger by about a year, died of a drug overdose in a Palm Beach hotel room while other family members were gathered at the Kennedy estate nearby.

Ron Galella / GettyRFK Jr. at a celebrity tennis tournament in 1972, the summer before starting college.

Ron Galella / GettyKennedy and his sister Kerry Kennedy, one of the family members who recently called for him to resign from government, in 1974.

Although Kennedy says he has not taken heroin since he got clean, he still considers his brain to be a sort of “formulation pharmacy,” able to transform anything—rock climbing, falconry, sex—into a drug. In 2024, New York magazine parted ways with its reporter Olivia Nuzzi after learning of what it deemed was an inappropriate personal relationship with Kennedy, whom she’d profiled the previous year. (After the print edition of this article went to press, more detailed allegations about his relationship with Nuzzi emerged. Kennedy declined to comment.) A former babysitter for Kennedy’s children told Vanity Fair that he had groped her when she was 23 and he was 45. Kennedy apologized to the babysitter in a text message after the article’s publication, though he said he did not remember the incidents she described. “I am not a church boy,” he said publicly. “I have so many skeletons in my closet that if they could all vote, I could run for king of the world.”

After his time in rehab in the early 1980s, Kennedy says he remade himself through the routines and principles of Alcoholics Anonymous—a combination of spiritual devotion, radical transparency, and a focus on service. As a presidential candidate, he told his security detail that he had to attend a 12-step meeting every day, no matter where he traveled. He has continued that practice since moving to Washington from Los Angeles. I asked him how much being an addict in recovery still affects him. “I think it’s shaped everything,” he said. Even as HHS secretary, he sponsors others in recovery. “I take calls all the time.”

[Content truncated due to length…]

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed