John Rawls famously claims that a just society is that one rational agents would endorse from behind the Veil of Ignorance. As he explains in A Theory of Justice, the society-designers in his thought experiment are maximally well-informed about all of the relevant third-person facts about, for example, how different economic systems would play out in practice, but

no one knows his place in society, his class position or social status, nor does any one know his fortune in the distribution of natural assets and abilities, his intelligence, strength, and the like.

Many of the consequences of this limitation are clear enough. Not knowing their race, they wouldn’t endorse anything like the racial laws of apartheid-era South Africa. Not knowing their gender, they wouldn’t endorse anything the gender laws of contemporary Saudi Arabia.

When it comes to economics, though, things are more complicated. Rawls thinks the society-designers (who are, remember, just trying to advance their own interests) might permit some distributive inequalities, if they were necessary to raise the economic floor for everyone. It’s true that, for all you know from behind the Veil of Ignorance, you’ll end up with the worst-off position in a less equal arrangement. But, you might still be better off than you would be in the more equal alternative with a lower floor. Rawls thinks that, as long as inequalities pass this test, and the better-off positions are available to all under conditions of “fair equality of opportunity,” there’s nothing unjust about the resulting distribution of resources.

G.A. Cohen disagrees, although Rawls and Cohen don’t disagree about as much as you might think. For one thing, this feels like a disagreement between a socialist and a defender of “the free market” but it’s really not. Many of the inequalities built into capitalist ownership relations pretty clearly fail Rawls’s tests, which Rawls himself—in a characteristically cautious and tentative way—acknowledged in his 2001 book Justice as Fairness: A Restatement. I wrote about that here.

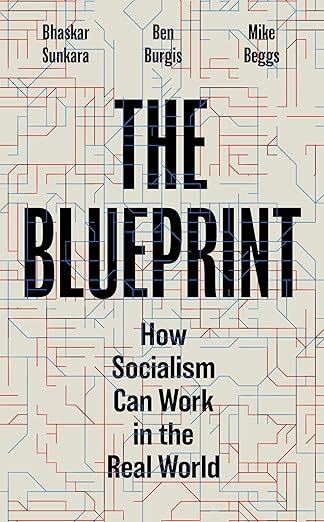

Let’s put capitalism aside, then, and think about what could come next. I recently wrote a book with Bhaskar Sunkara and Mike Beggs called The Blueprint: How Socialism Can Work in the Real World. (Out next year!) In it, we try to think through a grounded, realistic view of the kind of economy that we’d know how to implement “five minutes after capitalism.” Perhaps one day future technological progress or logistical insights or both will show our descendants how to get past the informational and incentive problems that plague attempts at totally marketless wall-to-wall economic planning. But, Bhaskar and Mike and I don’t think we need to wait for that to transcend capitalist ownership relations.

I previewed our model a while back and again last week. We’d considerably expand the fully public sector of the economy, crucially to commanding heights like energy, transportation, and finance. Businesses in the market sector would be partnerships between worker-owned firms and publicly owned banks, such that the workers would essentially be renting publicly owned means of production.

The bulk of our attention in the book is on trying to show that this would be economically viable (and thus that there is a realistic way of transcending capitalism at this stage of history). But, how just would it be?

Bhaskar and Mike and I are certainly committed enough egalitarians that, even in a scenario where class inequality has been ended, we’d worry about the extent of inequalities between more and less lucrative sectors of the economy, between different firms within sectors, and even within firms. Our model has a number of mechanisms to try to reduce all of these inequalities, from how grant payments work in different sectors to all the standard social democratic mechanisms for redistribution (now enhanced to the point that all adult citizens would receive one portion of their income directly from state funds) to state labor boards setting income benchmarks to limit any drive toward “self-exploitation.”

Even so, there are various sources of income inequality that we wouldn’t be able to eliminate entirely—at least, not without eliminating incentives we need to keep the economic wheels running smoothly.

To see the Rawls vs. Cohen aspect of all this the most clearly, let’s focus in intra-firm inequality. Existing worker cooperatives don’t have absolutely flat wage scales (even if they look that way compared to capitalist firms where CEOs might make hundreds of times the income of ordinary workers). It’s likely that income differences would be even more compressed in a world where worker-owned firms didn’t have to compete with traditional capitalist companies for managerial and technical talent. Even so, I expect workers would typically vote for wage scales that enticed people to take various kinds of jobs by offering higher salaries.

On one end, there are dirty and dangerous jobs. Under capitalism, sheer desperation produces a steady supply of applicants, but given more egalitarian background conditions, people would presumably have to be enticed with better renumeration. On the other end, there are jobs requiring rare skills or talents and/or involving lots of stress and responsibility.

On both ends, there are cases where this might not really violate strictly egalitarian principles at all. Different people value different things, or weigh how much they value each thing differently, so different packages of goods like physical comfort and safety, higher consumption, or more free time might give everyone exactly as much of what each person values. But, there are also many jobs that you’re more likely to be able to do (or at least be able to do well) not just because of the years you invested in your education, but because of the starting point you have due to your innate talents. To the extent that this is what gave some people the bargaining power to command higher wages (even in worker-owned firms), is the resulting inequality unjust?

This is where we arrive at a genuine Rawls/Cohen disagreement. The inequality I’ve just described would pass Rawls’s tests. In fact, sticking to the narrow context of the inequality within each firm, this is a particularly easy case for Rawlsians. We don’t have to think about what people would choose from behind the Veil of Ignorance where they thought they might end up holding the short end of the stick. The people left holding it know they’re holding it and they actually get to vote on the lengths of each stick-end.

Nevertheless, Cohen thinks there’s some injustice here. As it happens, I agree.

Here’s a second way in which Rawls and Cohen don’t disagree about as much as you might think:Their disagreement about whether distributive injustice remains in scenarios like this one doesn’t mean that they would necessarily, like, vote differently if they were both still alive and a referendum were held tomorrow where the three options were to (a) stick with capitalism, (b) implement Blueprint-style market socialism, or © take another shot at economy-wide planning and hope that it goes better than it did in the state socialist experiments of the twentieth century.

Cohen agrees that, as Rawls memorably puts it in A Theory of Justice:

Justice is the first virtue of social institutions, as truth is of systems of thought.

Where things get more complicated is that Cohen might disagree with the next line (depending on how it’s interpreted):

A theory however elegant and economical must be rejected or revised if it is untrue; likewise laws and institutions no matter how efficient and well-arranged must be reformed or abolished if they are unjust.

Cohen formulates his view about distributive justice as “luck-egalitarianism” in his more academic work, and as “socialist equality of opportunity” in his more popularized short book Why Not Socialism? Basically, he thinks inequalities are unjust to whatever extent they’re outside of the control of whoever’s left worst off.

But, that doesn’t necessarily mean that he thinks the overall right thing to do, at any given time, is to reform or abolish any distributive arrangements that fall short of the luck-egalitarian ideal. Cohen thinks that the pursuit of distributive justice has to be balanced against other important considerations, and he explicitly includes economic efficiency on that list.

While Rawls is very concerned about nailing down a precise “lexical ordering” scheme to figure out what to do when different principles collide, Cohen is comfortable acknowledging that some things are loose and fuzzy judgment calls. (If you really know your twentieth-century history of analytic philosophy, you’ll recognize this as a difference between how Cohen’s academic mentors at Oxford operated and the way that Rawls and his friends did things at Harvard.) Nevertheless, if we try to push on exactly when Cohen would be likely to say that economic efficiency can trump distributive justice, it seems likely that the circumstances where Cohen would see an injustice that we have to live with at this stage of history, though we should try to figure out how to get rid of it later if we can would look a whole lot like the circumstances where Rawls would see an inequality that wasn’t unjust because it conforms to his “maximin” principle (maximizing the minimum position).I’m inclined to think, though, that there’s more than just a semantic difference here. Cohen wants us to focus on the luck-egalitarian ideal as our north star. So, even if he and Rawls both voted for option (b) in the referendum, Cohen would be less satisfied with the result than Rawls. He’d want us (or our descendants) to restlessly continue to look for ways to go even further in an egalitarian direction when that becomes possible.

As I’ve said, I pretty much agree with all that. I view the model in The Blueprint as the best we know how to do at this stage of history, rather than as the endpoint of human progress.

That said, I don’t agree with all of Cohen’s reasons for holding this position. And the more I’ve thought about why not, the more it’s made me dwell on a question someone asked me years ago at a conference. (I didn’t have a good answer at the time.)

The conference was in late 2021 or early 2022, and I doubt this was the exact wording, but the gist of it was something like, “What does your luck-egalitarianism entail about an overall moral theory?” or “What does your luck-egalitarianism say about interpersonal morality?”

Part of the reason I didn’t have a good answer was that my immediate, instinctive answer was “nothing” (or at least “very little”). But, I don’t remember saying anything very convincing about why not.1

One way of fleshing it out might go like this:

Luck-egalitarianism is a position on what counts a just distribution of resources. While that’s certainly a moral question, a position on this one particular question might be consistent with lots of different positions on lots of other moral questions.

Probably, that’s what I would said in the moment if I’d been thinking a little more clearly. And I still think it’s a reasonable answer as far as it goes. But, I think we can expand on it in an interesting way, inspired by Rawls’s turn of phrase about justice being the “first virtue of social institutions.”

There’s an aspect of the Rawls/Cohen disagreement buried in that phrase “of social institutions” that I haven’t broached yet. It’s going to be central to the rest of what I have to say, though, so let’s go ahead and broach it now.

Rawls believes in something called the “basic structure constraint.” This means that he thinks that the proper subject matter of a theory of justice is the basic legal, political, and economic institutions of a society. Interpersonal morality is a different subject.Some of Cohen’s arguments against accepting even maximin equalities as unjust relies on rejecting this constraint. Cohen thinks that it’s unjust not only for institutions to be structured but for individual people to behave in ways that result in inequalities outside of the control of the worse-off.

Thus, in his book Rescuing Justice and Equality, Cohen analogizes agreeing to pay people with useful natural talents more to entice them to put those talents to use to work for the common good to paying ransom to a kidnapper so he returns your child. It may be true that the parents have a moral obligation to their child to pay the kidnapper, but that doesn’t mean that in a situation where the ransom has been paid and the child has been returned, nothing immoral has taken place. Cohen obviously doesn’t think playing hardball in wage negotiations with the rest of your worker cooperative (or just gravitating to the one that pays best for jobs like yours) is as bad as kidnapping, but he does think that the principles of justice give talented people a reason not to do so.

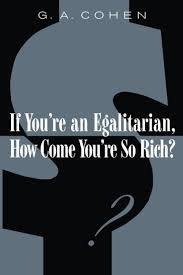

In 1995-6, Cohen gave the Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh. These were later revised and edited into a book I have very mixed feelings about called, If You’re an Egalitarian, How Come You’re So Rich?

A few years ago, when I was carrying it around to read it, my standard joke when people asked about it was that my goal is to get to a place in life where asking that question would be a good way to own me.2 In all seriousness, though, I just disagree that the question in the title is a particularly compelling one. My feelings are mixed because I liked most of the rest of the book. When I got to the part the title is drawn from, though, I got pretty impatient.

Cohen grew up in a working-class Jewish communist family in Montreal, surrounded by Communist Party members and fellow travelers. And interestingly enough, in If You’re an Egalitarian…, he awkwardly acknowledges that his family would have also rolled their eyes at that part of the book.

I was raised as a Marxist, in a working-class communist home, and it goes against my inherited Marxist grain to place wealthy individuals under what the Marxists of my childhood would have regarded as an unduly moralistic focus. I was taught, as a child, to concentrate my judgment on the unjust structure of society, and away from the individuals who happen to benefit from that injustice.

In other words, the comrades back in Montreal would have been on Rawls’s side. In a less philosophically well-articulated way, they all basically accepted the basic structure constraint. I think they were right, and Rawls was right, and that this is all entirely consistent with anti-Rawlsian luck-egalitarianism as a view about the design of social institutions.

Some of my family members were also involved in the socialist Left in one form or another at different times. My upbringing was very different than Cohen’s, but I got generally sympathetic answers when I asked questions about Marxism and socialism, and I too arrived at my politics at a pretty early age. So, maybe one of the reasons all this bugs me so much is that Cohen’s individualistic moralizing about what people are obliged to individually give away to charity goes against my own “inherited Marxist grain.”But, I also think there’s a more philosophically interesting question lurking in all of this about how to think about different domains of moral discourse. The way I’m increasingly inclined to think of it is that the larger issue is the relationship between justice and virtue.

If you want to think hard about virtue, a good move is always to go back to Aristotle. Without endorsing all the details of his moral theory, the man was, as Marx says several times in Capital, “the greatest thinker of antiquity.” Certainly, he’s the first person whose writings have survived who thought in a really deep and thorough way about some of these topics.In Aristotelian terms, “virtue” can mean two things. The broad way of using it is to describe the specific excellence of a thing—so, the “virtue” of a knife is to be sharp. The narrower and more usual way of using it is to talk about the kind of excellence most appropriate for human beings, which is living a good and “virtuous” life. Specific virtues like bravery or compassion help get you to that more general kind of virtuousness.

The word “virtue,” in popular context, has taken on all sorts of connotations that are unhelpful here. (“Virtuous” sounds like it means being an annoying embodiment of a particularly puritanical and tiresome life-ideal, and there’s even a Victorian sort of association about sexual ‘virtue’ that continues to float around in popular uses of the term.) But, “a virtue” in the sense I’m talking aboiut just means something like, a positive character trait, such that someone who has enough virtues that have been developed enough can be reasonably counted as a good person, someone living the way they should. And even if you aren’t accustomed to thinking about it in these terms, just about all of us do in fact have some vision of what counts as a good person or a well-lived life.

Rawls’s phrase about justice being the “first virtue of social institutions” nicely bridges the gap between the broader and narrower Aristotelian uses of the term “virtue.” Rawls is using the term in a moral way, but he’s also using it in a way that reminds us that different kinds of entities can have different kinds of characteristic virtues.

Human institutions are made of individual human beings, but that no more means Margaret Thatcher was right to say that there’s no such thing as society than tables being made of molecules means that there’s no such thing as a table or that everything that’s true of each individual molecule is true of the table. Similarly, Aleksandr Dugin is wrong to deny that individual human beings exist as morally important entities in their own right, with their own lives to lead, and to say that the individual no more has rights against society than the parts of your body have rights against you.

Individuals exist. The social institutions they come together to constitute exist. And these two kinds of entities have different characteristic virtues.

If we can figure out a good way to make the economic wheels turn without markets (and hence in greater conformity to luck-egalitarian ideals) at some point in the future, I agree with Cohen that we should do so. I find luck-egalitarianism more plausible than Rawlsianism as a theory of which institutionally generated inequalities should be troubling and why.In other words, the part of Cohen’s argument for that conclusion I’m on board with is that, in trying to build pragmatic considerations into his conception of justice itself, so he doesn’t recognize anything unjust about the result of historically necessary pragmatic compromises, Rawls gives us less moral clarity instead of more.

This is how I put it in an essay here last year:

Politics….is full of heartbreaking tradeoffs. Sometimes the trade is worth making. But, let’s at least be clear-eyed about what’s being traded away.

To the extent that this is his point, I’m with Cohen. But, to the extent that some of his arguments rely on rejecting the basic structure constraint, I get off the bus. The ransom analogy, for example, leaves me pretty cold.

Trying to work out all the details and give a fully convincing positive argument for this combination of views would be a massive undertaking, but right now I want to at least clarify how, and at least gesture at why, I diverge from Cohen on this point.

I think that what makes a social institution a good institution is a fundamentally different question from what makes a person a good person. Of course, the two questions overlap. They just don’t overlap the way Cohen thinks they do.

Here’s Cohen’s view:If you have a bigger share of society’s resources than you would in a luck-egalitarian utopia, this gives you reason to give your money away to those who have less, in the same way that considerations of distributive justice give us a good reason to support socialist politics on the institutional level.3Of course, Cohen acknowledges you might have other good reasons to act in other ways, and that you have to balance those other reasons against your commitment to egalitarian justice. For example, if you have children, your special obligation to them might give you a reason to make sure you have enough that you’d always be able to help them if they need it. But, once all the competing considerations have been properly weighed, Cohen seems to think anyone who cares about luck-egalitarian justice will for that reason give some away at least part of their excess wealth.

Here’s my view:Distributive justice and personal virtue overlap in the sense that a good person living in a bad society would want to do their bit to bring about a good society. And a good person who lives in a good society would want to be a good citizen of that society, helping to perpetuate its institutions.Crucially, a good society means (at least in so far as we’re thinking about distributive justice) a society whose economic institutions don’t tend to generate inequalities that are outside of the control of the worst off. If you live a society as bad as ours, you can contribute to the fight to make it a better one by doing things like organizing a labor union at your workplace or joining one if it’s already up and running, not crossing other people’s picket lines, and voting for socialist political parties. Some people, of course, will do much more than this, and there can certainly be something especially virtuous about that, although it’s still only one component of an overall good life. I’m not in favor of turning yourself into a robot for the cause. But, I do think that, within reason, you should try to make yourself useful to the cause as one aspect of how you conduct yourself as a well-rounded human being.

Speaking of being a well-rounded human being, here’s a second way that justice and virtue overlap:A good society would be one in which it would be easier to be a good person, living a good life. There are virtues it’s a lot easier to cultivate when we don’t all have to scramble over each other to climb up upward-mobility ladders, or when we don’t have to learn to avoid eye contact with the homeless so we can psychologically function in the presence of persistent poverty. The desirability of more people getting to be virtuous in these ways is another reason, in addition to distributive justice properly speaking, to fight for a better society. But again, that’s a fight that takes place at the level of economic and political institutions.

If you have lots of money, giving some of it away to help people in need is a virtuous thing to do, because it’s a compassionate thing to do. But that has nothing whatsoever to do with distributive justice. Losing sight of that distinction takes our eye off the ball. And whatever else Cohen’s Stalinist relatives in Montreal may have gotten wrong when he was growing up, they were absolutely correct about the location of the ball.

Thanks for reading Philosophy for the People w/Ben Burgis! This post is public so feel free to share it.

In fact, I think I probably just said, “Hmm, let me think about that.”Not one of my best moments.

Podcasting, freelance writing, and adjunct-ing all being what they are, that probably won’t happen any time soon.

In both cases, Cohen doesn’t claim that luck-egalitarianism is the only reason to do these things, just that it gives us a reason to do them.

From Philosophy for the People w/Ben Burgis via this RSS feed