This article by Elena Poniatowska originally appeared in the November 23, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper.

Mexico. In the Santa Martha Acatitla prison, the labor leader Valentín Campa was in charge of the apiary and all the prisoners, communists or not, loved the honey that could be bought in good-sized glass jars.

In the large courtyard of the cellblock, Valentín Campa came toward me completely wrapped in plastic sheets, his face covered with a mask, his hair hidden under a hood, and I could only recognize him by his voice. Behind him was the small garden covered in weeds that had nothing to do with the prison. Valentín knew everything about bees, and even more than about the Communist Party, he liked to talk to me about royal jelly. “Here, I’ll give you a jar so that when you’re old you can put this cream on your face because it’s magic and gets rid of wrinkles.” He offered me small bottles of royal jelly capsules that he had made himself, as well as the rejuvenating cream of which he was particularly proud. Is this communism or surrealism? I wondered.

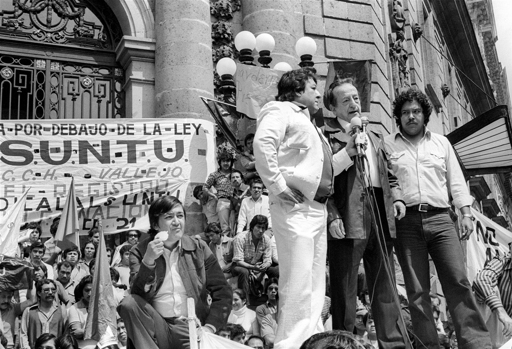

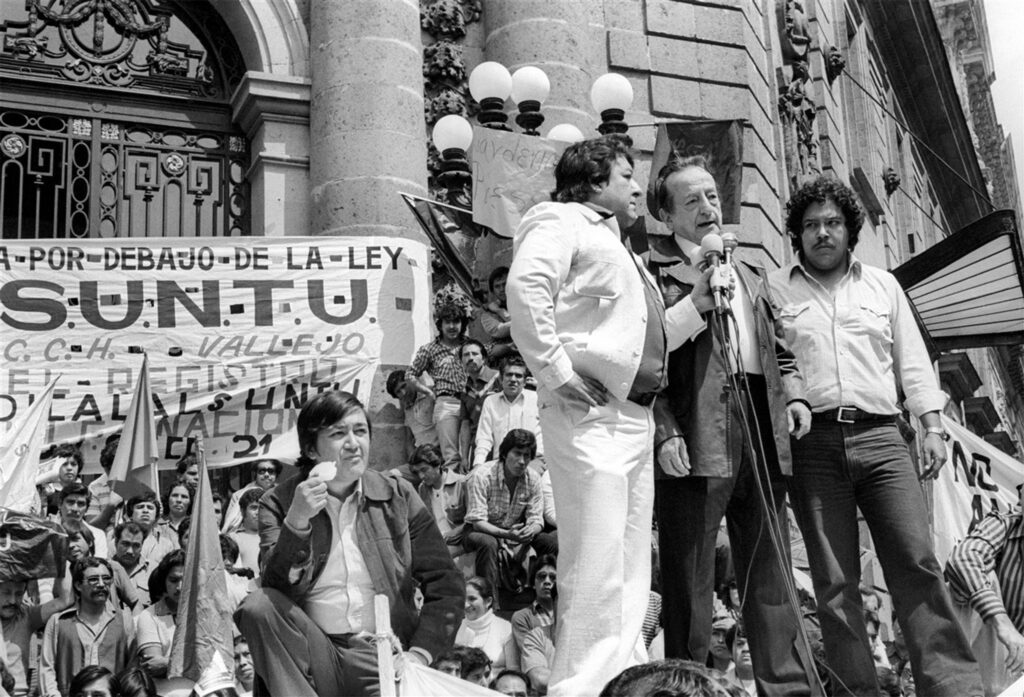

Valentín Campa in Santa Martha Acatitla prison

Demetrio Vallejo, in his immense and luxurious all-white room in the infirmary, was also a surreal apparition, because that place was his prison. Since he was constantly on hunger strike, and was very short in stature, he was barely visible, and even less so when on hunger strike.

“If you’re going to visit Valentín, don’t come see me,” he told me angrily.

I visited both of them, but especially Vallejo, because I intended to write about him as I did in Lecumberri prison.

“When you finish your Vallejo novel, will you do mine?” Valentín Campa asked.

María Fernanda Campa, daughter of María Consuelo Uranga and Valentín Campa, was destined to become a social activist with that background. She was a vibrant and decisive woman, and I must have seemed like a surreal “privileged girl” to her with my obsession with writing about prisoners, jails, and orphans. María Fernanda Campa always had a smile on her face. Even when she entered the Lecumberri Black Palace to see her partner, Raúl Álvarez Garín, she did so with a fighting spirit and a will to survive, inherited from both her father and mother, which ran in her blood. We became friends during Sunday visits, first in Lecumberri, then at the jail on the road to Puebla.

In Lecumberri, Chata (as María Fernanda was known) signed up on the visitor list of Raúl, her husband and the father of her children. He also received visits from his mother, Manuela Garín de Álvarez, who brought food to all the prisoners. They were the ones who advised me to sign up on Gilberto Guevara Niebla’s visitor list, because each prisoner was entitled to four or five visitors every Sunday, but since Gilberto had been born in the north, he had few visitors and it was easy to get on his list.

A visit to the prison always shakes things up and brings you closer to life and death, to freedom and its deprivation, to sadness and to the hope contained in a small phrase that we all repeat like a refrain: “You’ll be out soon; you’ll see that it will all be over soon.”

Campa gave his life to the Communist Party, but he also gave it to the landless, the peasants, the workers, convinced that our country would only become stronger and be for everyone when “we all went to sleep having eaten more or less the same thing.”

“Respect for constitutional freedoms is essential,” Valentín Campa would say, and I would listen to him with respect, even though I knew nothing about laws, nothing about prisons, nothing about injustices and very little about the war, because my mother, Paula Amor, decided to bring my sister and me from France, and although my father, a captain, stayed to fight with De Gaulle, his “V Mail” letters could not give a single piece of information.

Since when have you thought like that, Valentín?

“Since I was 14. I started in the oil industry. At 15, in Coahuila, I was a stevedore on the railroads.”

Weren’t you laying sleepers?

“The ‘sleepers’ were the railroad workers who did not fight for their rights.”

The confidence and conviction with which Valentín spoke inspired great respect in me for this man, always surrounded by bees, as if his ideals were a field in bloom. Today, many years after his death, I remember him with this interview in which we conversed surrounded by bees.

“My first union position was in the Confederation of Transport and Communications, and later I was appointed secretary of the Divisional Council.”

Were you haranguing people?

“Yes, they called me The Bolshevik.”

And wasn’t the CP in bad shape, as it always has been?

“Not always. I joined the party on February 21, 1927, one day before the railway strike, which was the cause of my first imprisonment.”

How many times have you been imprisoned? More times than José Revueltas?

“I’ve been imprisoned 11 times over the course of 14 years: twice in 1927. Calles ordered my execution, and Portes Gil (then governor of Tamaulipas) intervened, saying that my death would cause a conflict. Here in Santa Martha, where you see me, I’ve been here almost as long as Demetrio Vallejo. Miguel Alemán imprisoned me for three years and two months. On other occasions, I’ve been imprisoned for one or two days, even up to three months, not counting the five years I spent in jail when Plutarco Elías Calles was president.”

So, how many years has it been so far that you’ve been a beekeeper, surrounded by the buzzing of bees?

“Things went very badly for me under Calles. I was persecuted for a year and two months after the Railway Workers’ Union uprising. In total, seven years and four months of persecution. Every president has arrested and imprisoned me: Ortiz Rubio, Calles, Abelardo Rodríguez, Portes Gil, Ávila Camacho, Miguel Alemán. Andrés Serra Rojas saved me from going to the Islas Marías in 1930. He was a public prosecutor and was later dismissed. We were imprisoned because a priest shot Ortiz Rubio, leaving him with a crooked mouth.”

Living with Valentín Campa must have been difficult. Consuelo Uranga, Valentina, and María Fernanda Campa must have had a very hard time. Of course, Valentín Campa was a central figure in the Mexican labor movement; he would give his life for his ideals. And although Consuelo Uranga, the mother of his children, was also a great social activist, she couldn’t have lived a peaceful or happy life. “When a man marries his ideals, there’s no room for any other relationship. Political passion consumes everything.”

In 1970, Vallejo and Campa, despite their falling out, left Santa Martha Acatitla prison together. Vallejo, who had been released an hour earlier, had to wait for Campa at the exit gate, surrounded by a throng of photographers and journalists. The two leaders, who hadn’t spoken to each other in prison, had to embrace and shake hands in public. All eyes were on Demetrio Vallejo, because his hunger strike of more than 10 years and his insolent responses, published in the newspapers, had made him a singular figure. As the gate opened, Valentín declared to the press that he was leaving free “without altering my political convictions in the slightest,” and that he wasn’t afraid of returning to prison.

What was I doing in Lecumberri and Santa Marta? Who suggested it might be a good way to get to know and connect with those who didn’t have my privileges? Now there I was, under the sun, with my tape recorder, and at the newspaper Novedades the news editor would also ask: “Elena, what are you doing?”, just as I was asking Campa right now:

What was your life like in prison, Valentín?

“I kept myself in the best physical and mental condition.”

And Vallejo?

“He remained in the infirmary.”

Did you feel abandoned?

“Never. I did notice a decrease in solidarity, for example, before the 1968 student movement, because there were smear campaigns that frightened people. But we felt supported by railway workers, laborers, students, Cardenistas… But I would like to emphasize that the student movement gave a great boost to the struggle for the freedom of political prisoners.”

Now that I can go back from 93 years old to 30 or 40, and remember my privileges, I believe that two great opportunities to love Mexico were given to me by the railroad workers imprisoned in Lecumberri, in the 60s, and by wanting to interview people I would never have met if I hadn’t been a journalist.

Elena Poniatowska is a French writer, journalist and activist who settled in Mexico during World War II and one of Latin America’s most distinguished and innovative living writers.

Valentín Campa

November 24, 2025November 24, 2025

Valentín Campa gave his life to the Communist Party, but he also gave it to the landless, the peasants, the workers; convinced our country would only be strengthened & belong to everyone when “we all went to sleep having eaten more or less the same thing.”

Mexican Farmers Occupy US Border Crossing, Protesting Agricultural Policy

November 24, 2025November 24, 2025

Campesinos are demanding the federal government craft a sovereign agricultural scheme & leave the speculative market of the Chicago Stock Exchange, which forces prices well below production value.

Supreme Court Re-Opens Coca Cola Tax Debt

November 24, 2025November 24, 2025

For decades, a neoliberal-captured Supreme Court allowed corporations to evade and defer massive tax debts to the Mexican state. Recent rulings suggest that era may be over.

The post Valentín Campa appeared first on Mexico Solidarity Media.

From Mexico Solidarity Media via this RSS feed