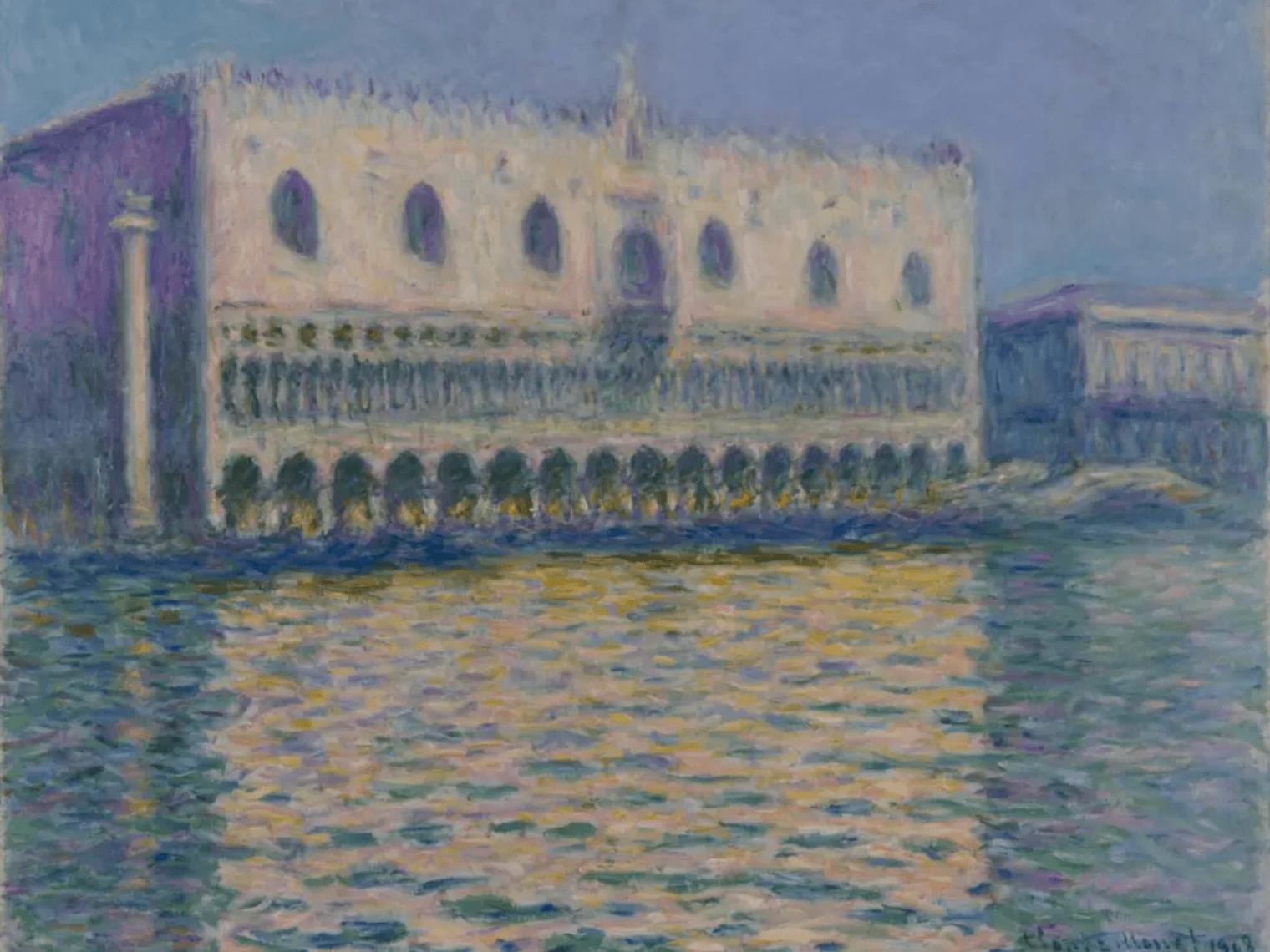

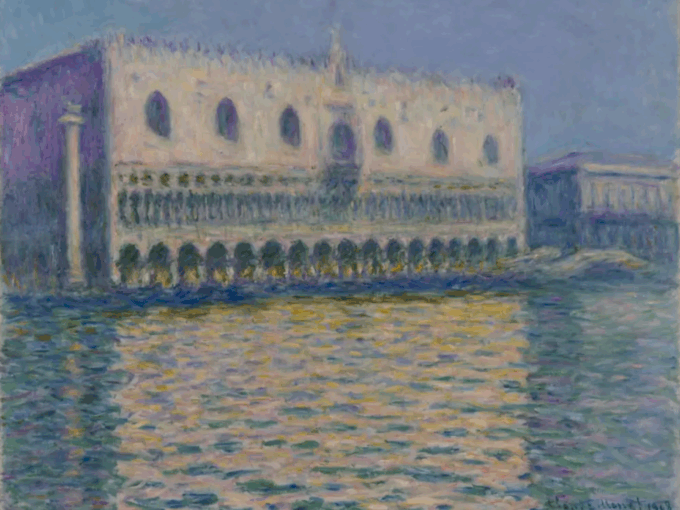

Claude Monet, The Doge’s Palace, 1908. Brooklyn Museum

Monet and Venice

The Brooklyn Museum

October 11, 2025 – February 1, 2026

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, March 21, 2026- July 26, 2026

“One could say, in fact, that Monet attempted to eliminate time as a variable to better concentrate on the interrelationships between atmosphere, light, color — and of course, how the water refracted these elements.”

Joachim. Pissarro, Monet and the Mediterranean

Monet is an excellent subject for an art exhibition, for he is an important, reliably stimulating painter. And also, of course, so is Venice, the home of Giorgione, Titian and all of their illustrious successors. For that reason, it too it is the subject of many exhibitions. But Monet and Venice is a slightly problematic theme. After all, Claude Monet only visited and worked in Venice once, relatively late in his career, in 1908, for just over two months, when he as 68. And so you could curate a major Monet show without including any of his Venetian paintings. By that point, his influential late aesthetic was well established, and it’s not apparent that he was open to further development. In Venice he did make 37 paintings in all, 29 of which are in this show, which is the first exhibition of these works gathered together.

We can view Monet and Venice as his version of such exhibitions as Canaletto and Venice, Guardi and Venice or Turner and Venice, reconstructions of a famous artist’s visual responses to this much-depicted city. Like his predecessors, Monet offers a striking view of Venice. No doubt, of course, one practical concern was also relevant to the curators here: Both Brooklyn and the San Francisco museum, which is the second site for this exhibition, own major Venetian scenes by Monet. But as I said, the problem with Monet’s response to Venice is that it was of relatively limited interest. Turner, who visited Venice repeatedly, worked in a style not unlike Monet. But he depicted a much greater variety of Venetian sites. Suppose you know the cityscapes of Canaletto, Guardi and Turner, which show the rich arrays of luxurious palaces, large and small Venetian boats, and richly dressed pedestrians. In that case, Monet and Venice will seem, in comparison, disappointing. In his paintings no Venetians are in view; the boats include just a few gondolas, generally seen in outline; and he choose to depict only nine distinctive motifs. Thus, we see the entrance to the Grand Canal, the Palazzo Ducale, San Giorgio Maggiore, the Palazzo Dario and just five other vistas. None of the paintings reveal the rich architectural details prominent in even banal photographic images of these Venetian monuments.

In Brooklyn, the whole presentation of this show is extraordinary. You entered through a gallery in which videos of Venice were projected on all sides, visually overwhelming. And then the galleries presenting the Monets are very dimly lit, which makes it almost impossible to read the wall labels. The display of numerous comparative works by other painters who visited Venice only emphasises the oddity of Monet’s pictures. Compare, for example, his works to the two small Corots, which are visually charming. Then you get to the large, circular room in which ten Monets are displayed. Music by composer-in-residence Niles Luther accompanies that part of the show. This controversial association of Monet’s paintings with music was developed long ago by Kermit Swiler Champa, a well-known scholar, in his Masterpiece Studies, Manet, Zola, Van Gogh, & Monet (1994). Oddly, there’s no reference to his account in the catalogue. The extravagant presentation, with video displays at the entrance and music in the last gallery, seems to overcompensate for the weakness of the main attraction, Monet’s paintings of Venice.

If this is the entire story, then Monet and Venice would be an unsatisfying exhibition. No doubt, as the catalogue explains, his interests were in part commercial. There was demand for his images of Venice. The Brooklyn Museum has chosen to focus on a relatively minor, visually frustrating aspect of Monet. I thought that the setting overpowered the art. The light show at the entrance and the dark galleries, with the art in a cave-like effect, seemed distracting to me. That was my initial reaction— that was what I felt until I got home and studied the catalogue. And then I realised there was another, totally different, much more satisfying way to understand this show. And I saw that if the pleasures of seeing picturesque Venice are absent from these pictures, that’s because Monet had other goals in mind in these paintings.

Let us understand Monet and Venice as a bold experimental anticipation of the 1960s conceptual works of Ed Ruscha, the photo realism of Richard Estes (who also depicted Venice) or (even!) Andy Warhol. Monet sought out motifs which would allow him to experiment. Look at the lower part of the painting in any of The Grand Canal, Venices (1908). You see all over fields of parallel strokes of painting, not unlike those in some 1960s abstractions by Joan Mitchell or Sam Francis. Here, mostly detached from its figurative uses, is a luxuriant field of paint. And many of these other pictures achieve the same effect by focusing on the bottom portion of the image, showing the canal waters. In his catalogue essay “Monet’s Venetian Hours” André Dombrowski describes these ways that the artist divides his world, the upper solid architecture set above the waters. That division makes possible the radical visual experimentation,

It’s easy, if we accept this analysis, to understand why Venice was a perfect subject for Monet. Under the guise of depicting this touristic site, he creates radically experimental pictures. That’s why Monet’s artworks contrast so drastically with the paintings by other artists used to fill out this show. I cannot recall an exhibition whose ultimate value depends so crucially upon how it is interpreted. The catalogue provides a great deal of information about Monet’s everyday life in Venice. But it doesn’t tell us how to choose between these two interpretations of the paintings he made there. Perhaps, indeed, there is no need to choose. Philosophers are familiar with the rabbit-duck, the visually ambiguous figure which can be seen as a rabbit or as a duck. Monet and Venice is, analogously, a visually ambiguous exhibition, which can be seen both as a presentation of his banal Venetian cityscapes and, alternatively, as his anticipation of all-over abstraction. As images of a traditional, much-depicted subject, Monet’s depictions of Venice may be minor. But as experimental artworks, they are very fascinating. I grant that, in making these radically original paintings, Monet certainly could not have anticipated 1960s abstractions. He was merely trying to paint a very familiar subject, the city of Venice, in a novel way. But now we can make a fuller sense of the significance of his pictures. And the visual context of this show, which includes many older and more traditional images of Venice, is now essential to understanding what he was doing. Recognising that the tradition of Venetian cityscapes had exhausted itself, he sought a novel way to respond to the city. And by seeing the many other, more traditional images, we are prepared to react to this deeply original achievement.

The post Monet and Venice appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed