Image by Eric Krull.

Political movements without music may still be called movements, but they are not worth joining. No recent scholarship on music and politics has proven this more thoroughly than that of anarchist graphic designer and archivist Josh MacPhee. Over the past decade, MacPhee has produced groundbreaking, encyclopedic work on the musical activity of twentieth-century left-wing and labor organizations. MacPhee’s An Encyclopedia of Political Record Labels (EPRL), first published in 2017, was a revelation for politically-committed musicians. Although MacPhee maintained the book was “not intended to be read from cover to cover, but to be bounced around in,” I vividly remember the intensity with which I systematically worked through my copy the day it arrived in the mail. Three years later, in 2020, MacPhee produced an equally essential addendum to the EPRL titled Bonus Tracks. In the years since, EPRL and Bonus Tracks have been my constant, dog-eared companions, aiding my research and practice as a politically-committed scholar of music.

The real intellectual thrust of the EPRL is the vast, international infrastructure of left-wing audio production it reveals and the resulting musical relationships it uncovers. Left-wing record labels like Chile’s Discoteca del Cantar Popular (DICAP), France’s Expression Spontenée, and the United States’ Paredon Records were part of a massive, interconnected means of audio production and distribution that structurally linked Víctor Jara to Bernice Johnson Reagon, Mikis Theodorakis to Carlos Puebla. As MacPhee points out, the development of this infrastructure followed a distinct historical arc. Its rise paralleled the mid-century consolidation of the international, capitalist recording industry around the technological format of the vinyl record. Its fall, too, corresponds with the disintegration of the physical-media-based capitalist record industry in the aughts. For a period of forty years, however, the international Left successfully appropriated capital’s model and means of audio production for its own ends, producing a massive archive of politically-committed music.

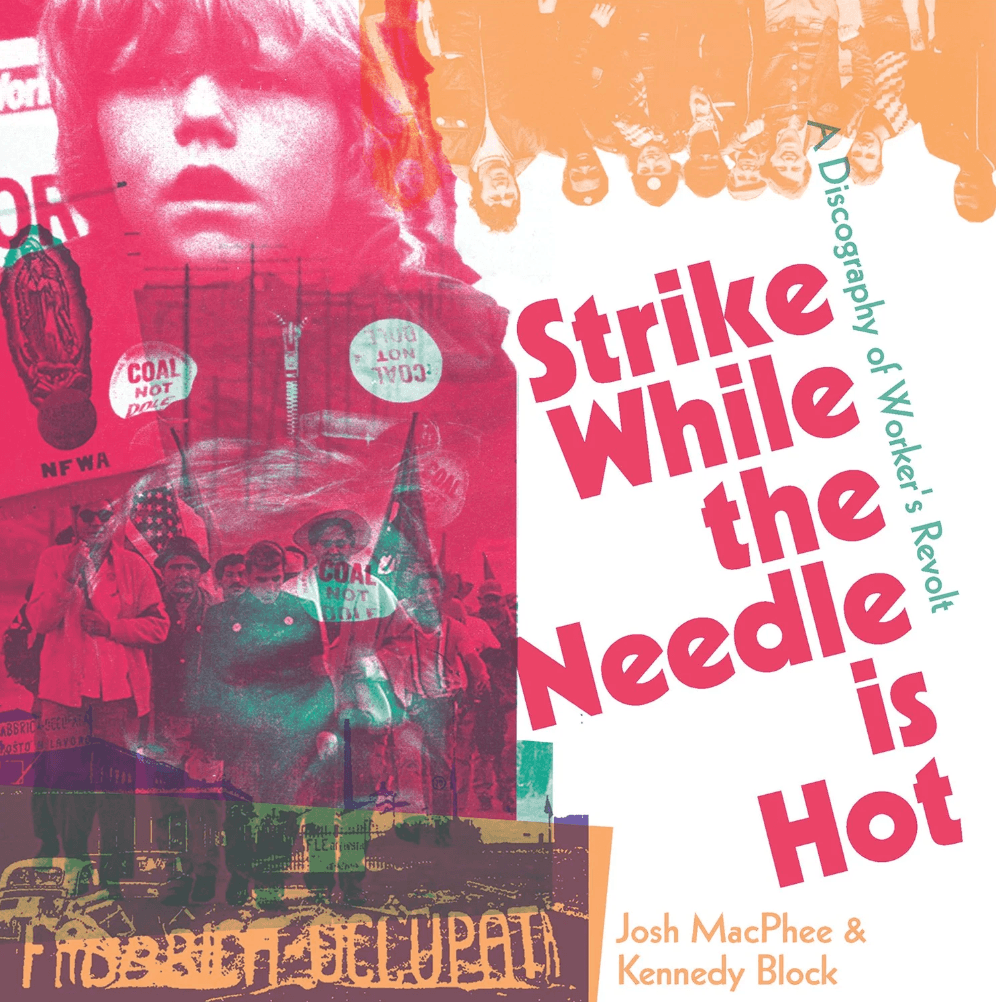

MacPhee, along with co-author Kennedy Block, has recently followed up the EPRL with an equally impressive work. Strike While the Needle is Hot: A Discography of Workers’ Revolt compiles and annotates eighty recordings produced by trade unions, workers’ organizations, and left-wing groups for specific strikes between (with one exception) 1960 and 1990.

While the EPRL provides a macroscopic view of left-wing and labor-affiliated vinyl audio production during this period, Strike While the Needle is Hot tacks in the opposite direction, offering a complementary, microscopic perspective on the same activity. As MacPhee puts it, each “entry drops you into a specific strike, more than likely a fight that has been forgotten, at least by those who weren’t active participants.” This approach allows MacPhee to draw more specific conclusions with regard to the strategic function of this activity than was possible in the EPRL. MacPhee’s analysis reveals “a plethora” of strategic objectives, “sometimes singular, other times multiple, often overlapping, and almost always clearly understood and articulated by the workers and unions.”

Unsurprisingly, vinyl audio production among left-wing and labor organizations was often mobilized to serve strike publicity and fundraising. An entire section of the book is given over to analyzing the tactical function of vinyl audio production in the service of these objectives during a single action: the 1984/85 UK Miners’ Strike. The sheer amount of records produced to publicize and fund the Strike provides MacPhee and Block the raw material necessary for a comparative analysis of “the fine grain variation in method and argumentation for something as clear and direct as donating to an official centralized fund.”

These records framed the miners in varying ways. Some, like a 1985 compilation produced for Northumberland and Durham miners titled Heroes, presented the strikers as protagonists, highlighting their active political role. Others, like the Chris Cutler-produced The Last Nightingale compilation, chose to emphasize the miners’ status as Christly victims “suffering their hardships to save not only their jobs but also the mining industry itself – a nationalized industry & therefore a national asset – for us, for the country as a whole.” It’s impossible to know who the intended market for each record was, but the competing discursive strategies were likely the result of different demographic targets.

However, one would be wrong to assume that the majority of left-wing and labor vinyl audio production served these strategic ends alone. Outside the 1984/85 UK Miners’ Strike, in which publicity and fundraising were primary, MacPhee and Block reveal that this activity often served more subtle, inward-facing goals. While publicity and fundraising always exist at the margins as secondary objectives, many records “foreground[ed] experimentation in culture, popularization, and research.” In other words, the strategic objective of many of these records was workers’ construction of an alternative civic space to those provided by capitalist firms and the state.

Vinyl records in the twentieth century were a particular kind of capitalist commodity. They not only served to realize surplus value, but, like all so-called “cultural” commodities, reproduced the social continuity of capitalist civilization through their critical consumption. The shared, cross-class experience of consuming capitalist popular music daily reintegrated capitalist civilization’s discontinuous social elements, reproducing the shared, usually national, subjectivity of worker and owner. Musicians involved in the capitalist recording industry could resist this logic to a certain extent, composing material that, through musical and lyrical persuasion, impaired the smooth process of consumption. But the records MacPhee and Kennedy present do something fundamentally different. They break the logic of the capitalist recording industry rather than subvert it. While the EPRL uncovers the complex result of many thousands of these breaks, Strike While the Needle is Hot examines the simple particularity of small exertions of agency, from which each record emerged as a crystallization of workers’ autonomous activity.

The most profound insight of Strike While the Needle is Hot, as well as the EPRL, is the implicit postulate that workers’ appropriation of capitalists’ means of producing subjectivity is fundamental to proletarian liberation. Audre Lorde’s famous aphorism, that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” is regularly invoked in US left-wing writing, yet a fundamental proposal of the socialist movement is the transformative expropriation of the owners’ tools by the workers. Both the EPRL and Strike While the Needle is Hot reveal the extent to which the twentieth-century international labor movement appropriated the means through which the capitalist recording industry produced a shared subjectivity between worker and owner: the vinyl record. Each time a group of workers appropriated this form for their own ends, they were, in effect, expropriating the capitalist recording industry of the monopoly it maintained over its use. The vinyl record was one tool in the masters’ collection, but workers transformed it into a weapon of their own.

The post Without a Discography, We Have Nothing: A Review of Strike While the Needle is Hot appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed