Photo by Magda Ehlers, via Pexels/Canva

Listen! Listen to the truth-tellers who renamed Thanksgiving a day of mourning. It started in Connecticut—but not the way we were told at school.

In 1637, the English colonizers carried out a pre-dawn raid on a Pequot community. When the Pequot fought back against the marauders, the English brought firebrands into the wigwams, and set the villages afire. They killed hundreds of Pequot villagers—adults and children alike. And then the colonizers celebrated this spectacular obliteration of a people who had lived in a place for ten thousand years. Governor John Winthrop of the Massachusetts Bay Colony made the massacre date.) an annual holiday.

Surviving Pequot were executed, or sold into slavery.

Rick Green described it in 2002 in The Hartford Courant:

Among the Pequots caught in the bog in what’s now part of Fairfield, a group of perhaps 17, mostly children, were thought to have been exported as slaves. Others were handed out to soldiers as wartime booty. Historians believe these 17 Pequots later ended up on an island off Nicaragua. Like many of the Indian slaves sent from America over the next century, there is little record of what happened to them.

The Treaty of Hartford (1638) declared that any Pequot still alive could no longer return to their land, or even exist as Pequot. The Pequot language went extinct.

This story became a series. All told, the U.S. colonizers would pull more than 1.5 billion acres out from under Indigenous people. Upon these violent takings, U.S. history took shape.

According to the New Haven Museum, George Washington dubbed Thursday, November 26, 1789 a day for “public thanksgiving and prayer” in the first U.S. capital, New York City. Abraham Lincoln re-affirmed Thanksgiving as an official federal holiday in 1863—not even a year after greenlighting the nation’s largest ever mass execution—the hanging of 38 Sioux in December 1862.

Trump wasn’t around to build a Riviera at the Mystic Seaport, where the Pequot once lived. But the place has been duly developed, with gaudy distractions, including an aquarium that touts “exciting up-close-and personal interactions” with trained seals, sea lions, and penguins—so-called “animal ambassadors” who could have lived free if we hadn’t ripped them from their habitats. The impacts of colonial exploits on our natural world and its living communities tend to mirror the impacts we have on each other.

The Lenni Lenape (Delaware) people once lived on the land where I write. Now, our local post office displays Alfred Crimi’s mural of General Anthony Wayne, sword in hand and eagle on shoulder, wearing tall riding boots and literally stepping over the dying bodies of Native people at Fallen Timbers.

As the colonists moved, they assigned much of the land they took to the states. Land-grant colleges slathered animal agribusiness over the Great Plains. To this day, we bury the land under feed crops, feedlots, herbicides and pesticides because we fail to respect the interests of river otters, whooping cranes, burrowing owls, long-billed curlews, black-footed ferrets, wolves, coyotes and kit foxes. U.S. territory leads the world in extinctions of nonhuman life.

We need to protect and restore what’s salvageable. We need to appreciate the role of every living community on this one and only Earth. To say “no” to the weapons and the wars; to take down the walls. To understand that genocide and ecocide must never be excused, let alone celebrated.

But What Shall We Have for Dinner?

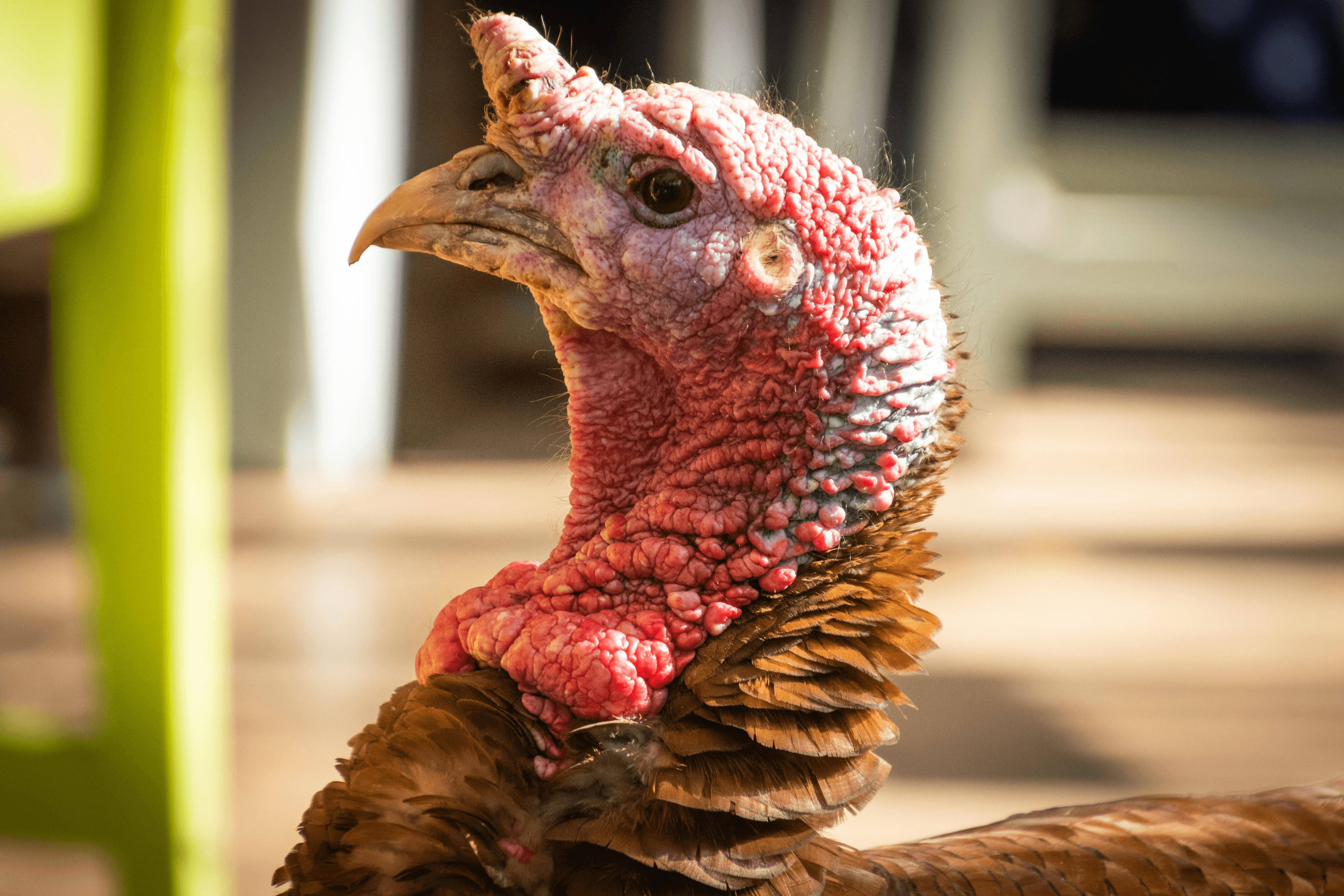

Let me share my signature dish with you. I haven’t eaten a turkey’s body since the 20th century. For this, I give thanks. I received a recipe for holiday cashew nut roast from my friend Robin Lane in 1983. It became my annual tradition. No chasing; no killing; no cooked body; no bones. Give it a try.

Coarsely grind two cups of cashews, by running a rolling pin or jar over the bagged nuts. In addition to the cashews, gather these ingredients (organic, to the extent possible):

4 ounces (before cooking) brown rice;

6 ounces of rye toast crumbs—including the caraway seeds (or add a dash of celery seed);

1 medium onion, chopped;

2 cloves garlic, minced;

2 large, ripe tomatoes;

4 tablespoons olive oil;

Up to ¼ cup vegetable broth;

2 teaspoons brewer’s yeast powder;

A teaspoon of blended dried basil and thyme; and

A squeeze of lemon and a pinch of ground pepper.

Cook the rice; then mix it with the ground cashews. Chop the onion and garlic finely; brown them in a slightly oiled pan. Chop one tomato and simmer it with the onion and garlic, adding a wee bit of broth. Combine all (except the second tomato) and press into two pie baking dishes.

Decorate the top of the roasts with slices of the second tomato. Dab olive oil and pepper over the slices. Bake at 350°F / 175°C for 30 minutes or a bit longer until the top begins to brown.

And as we sit down to share our meal, may we stay mindful of the colonial violence that rages in some areas, and reverberates in others. From Palestine to the sacred Sioux territory wanted for pipeline construction, to the communities, human and other, along any government’s border wall. May we defend and sustain those who resist. May we contemplate how an honestly humane humanity could emerge from our history, and all the discoveries it will make.

The post Make Thanksgiving Day History appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed