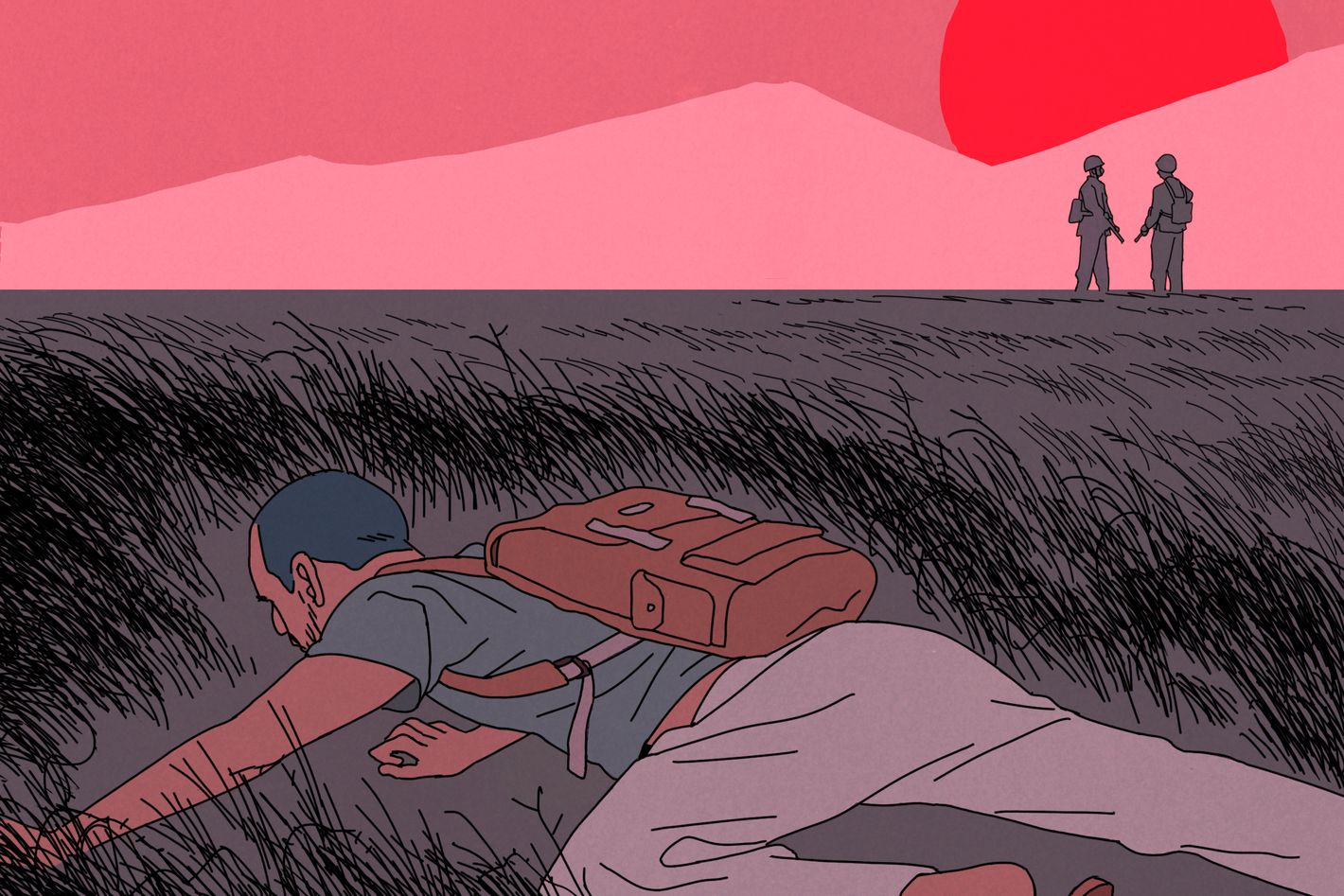

Illustration: Patrick Leger

One cloudy morning this past March, 36-year-old Aasis Subedi found himself back in the country his family had fled when he was 4. At the airport in Bhutan, he recognized the traditional bakhu dress of the approaching government officials; a surge of anxiety passed through him.

Subedi had arrived alongside nine other Bhutanese men who had immigrated to the U.S. legally but were deported because of criminal convictions ranging from substance abuse and trespassing to assault and burglary. Although they had been born in Bhutan, all the men were ethnically Nepali — a group that, beginning in the 1980s, was stripped by the Bhutanese government of their citizenship. Over the years, Bhutanese Nepalis have been imprisoned, tortured, and, in many cases, chased off their land and expelled from the country. Subedi’s family had fled in 1993, and he’d grown up in a refugee camp in Nepal before arriving in the U.S. more than a decade ago. Then, in 2023, he was convicted of sexual misconduct against a minor.

The deportees knew that Bhutan still does not recognize them as citizens and had heard that the country was still imprisoning ethnic Nepalis, so they were sure they were headed to jail. “We thought it was over,” Subedi said, “and we’d never see anyone we knew ever again.” Immediately after they landed, Bhutanese officials confiscated their belongings. They placed their documents in plastic bags and collected their phones, jewelry, watches, and cash. Subedi handed over the $575 he had carried with him from Ohio. Within a day, officials told him in a language he barely understood that he and the other prisoners would not be given legal status in Bhutan, but if they agreed to go to Nepal, Bhutan would offer them money for the journey. Subedi and the others were then loaded onto a bus with some plainclothes government agents. As they neared the Indian border, officials gave them around $300 in Nepali rupees and handed back their phones. Their documents were never returned to them.

For his crime, Subedi served a sentence of two years. Then, last November, right before he was scheduled to be released, he received a deportation order. Before Trump took office, Subedi would have likely been released from ICE custody despite that deportation order and allowed to remain in the country as long as he routinely checked in with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Deportations resulting from criminal convictions are common, but they were rarely, if ever, carried out if the countries of origin refused to accept the deportees, as was the case with Bhutan. But, in 2025, the Trump administration reportedly pressured the country to admit deportees under threat of being put on a travel-ban list. ICE also cannot, by law, send people to places where they may face persecution. All of which is to say that, prior to this year, deportations to Bhutan “simply were not happening at any kind of systemic level,” said Aisa Villarosa, an attorney at Asian Law Caucus.

Now, deportations and detainments of all kinds have been fast-tracked. Subedi was on the first deportation flight to Bhutan, and several more have followed. As of July, 53 Nepali-speaking Bhutanese have been deported to the country — then swiftly deported out of it. “I wouldn’t say that this is a very clear-cut third-country-removal situation, but it almost is in spirit because no one has been allowed to stay in Bhutan,” said Villarosa. As a result, Subedi and others have been rendered stateless — without rights or prospects to restart their lives.

They now live in Nepali refugee camps or in other temporary housing with no money or resolution in sight. One of them, a man named Sanjil Rai, was recently found dead by suicide. A second person has been debilitated by depression, unable to leave his home. The deportation has permanently exiled them into what Gopal Krishna Siwakoti, president of the Nepalese human-rights group INHURED International, calls a “black hole.” They are regarded by others in the refugee camp as failures who wasted their opportunity in America — or as beggars and criminals. Now that Nepal is in the midst of a rocky transition after months of violent protests, the possibility of getting any kind of status or rights grows even more remote. “My name is Aasis; people I know call me Aasis. But I have no ID, nothing,” Subedi said in Hindi. There is no country, he said, that he could call on for protection. “How can I prove to them I am who I say I am?”

Subedi grew up in the Khujunawadi refugee camp in Nepal, one of the seven in the Jhapa district that were set up in the 1990s in response to Bhutan’s ethnic cleansing of the Nepali-speaking population. He was 27 years old and driving a village taxi when the U.N. brokered his resettlement to the U.S. in 2016. That July, he said good-bye to his family and flew to Chicago, then to Omaha, Nebraska. With refugee documents in hand, he began work at a Tyson meat-processing plant. He was an “all-round” player, he said, working the labor line, operating machines, and serving in the factory’s frock room. At first, he felt intimidated by English, but he liked practicing with employees at work, many of whom were immigrants from Southeast Asia. They would often teach other snippets of their own languages, starting with the bad words. In 2018, he got his green card.

In 202o, Subedi moved to Missouri. There, he met his partner at a cheese company where they both worked, and they later moved to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where there is a large Bhutanese community. By 2021, his partner was pregnant. Their daughter was born the following year, but, by that point, their relationship had become strained. After one fight, Subedi left to stay with some friends in Ohio. Those same friends were the ones who called the police on him for sexually assaulting a young girl in the family. Documents noted that the victim was 12 at the time. By July 2023, he had spent 11 months in jail when a judge delivered a sentence: two years, credited for the time he’d already spent in pretrial detention, for “gross sexual imposition” — a serious felony in Ohio. It qualified as “a crime involving moral turpitude,” which is a broad category of crimes under U.S. immigration law that can be grounds for deportation. But having heard from friends and family that stateless Bhutanese were seldom actually deported, Subedi pleaded guilty without contest. He spent another ten months in prison post-conviction before moving to a Correction Reception Center, where incarcerated people are given classes to help them transition back to life outside prison.

Then, in August 2024, two days before he was set to be released, ICE picked him up and took him to the Seneca County Jail in Ohio. There, Subedi learned that the government does not provide lawyers for immigration cases. Money in his household was tight; the whole time he’d been in prison, the family had been dependent on the goodwill of friends and family, so Subedi didn’t feel like he had any right to hire a private immigration attorney. He decided to represent himself and filed for asylum as a defense against deportation. In his application, he wrote that his father, who remained back in a refugee camp in Nepal, was beaten back in 1993 by the Bhutanese government. He feared mistreatment and torture, he said, if he returned. “Yes, I fear because I am child of the person who was severely harmed,” he wrote. Nevertheless, three months later, an immigration judge ruled that he could be deported to Nepal or Bhutan. He waived appeal because he still didn’t believe he would be deported — a belief, he said, ICE officers confirmed up until this March.

After receiving a deportation order and an asylum denial, immigrants still have legal options. Lawyers can file motions to reopen and reconsider a decision, for instance. But, after Trump took office, ICE’s policies changed. Deportations started happening suddenly and without transparency or due process on a wider scale than ever before. “There simply wasn’t any human amount of time to assess individual legal cases or to look for those possible challenges,” Villarosa, the attorney, said. “Even seasoned lawyers were caught off guard.”

It was only after Subedi was flown to New Jersey and given a boarding pass that clearly stated he was going to Bhutan that he understood what was happening. Panicking, he asked to speak with his family through a video call. He wanted to see his daughter. But when she came on-camera, he wasn’t sure what to say except a hasty good-bye.

Advocacy organizations often avoid the subject of immigrants with criminal convictions, focusing instead on sympathetic stories to counter the widespread (though inaccurate) claim on the right that immigrants commit crimes at higher rates. Because of their records, Subedi and the other deportees to Bhutan all fit the description of the type of immigrant the Trump administration says it is targeting, even though most of the immigrants currently in custody have no criminal records and many of the ones that do have committed minor offenses like traffic crimes and DUIs. While Democrats also prioritized expelling immigrants with criminal records, the Trump administration has put deportations of this group on hyperdrive — and sent them to third countries with unprecedented frequency.

Cubans with criminal convictions have been deported to Mexico; Laotians and Vietnamese were expelled to South Sudan, even though it is in the midst of a violent conflict. A Jamaican man who served a 25-year sentence for murder was working at a men’s shelter when ICE picked him up and deported him to Eswatini. A number of African migrants with criminal records were recently sent to Ghana, after which some were repatriated to their home countries they fled in fear for their lives — in violation of U.S. court orders. Some of the Bhutanese refugee convictions were decades old, according to the Asian Law Caucus, while others may have been a result of heavier policing of refugee teens. A few Bhutanese were deported for crimes that no longer meet the criteria for deportation, like substance use or trespassing.

Many have been deported after serving out their full sentences — “What we call double jeopardy or double punishment,” said Jeff Migliozzi, communications director of Freedom for Immigrants. Those who are thrown into what Migliozzi refers to as the “prison-to-ICE pipeline” tend to be long-term legal immigrants — permanent residents and immigrant-visa holders — who have spent a substantial amount of time and established deep roots in the U.S. Effectively, the system is “punishing people twice, or in this case, even three times, based on where someone was born,” he said. “That is the deciding factor here — if they were born in the United States, they would otherwise be going home.”

Subedi and the two men in his car crossed into Nepal after convincing one of their drivers to help smuggle them in from India. They walked across on foot for hours in open-toed shoes through brambles and stones to cross from West Bengal, India into Kakarvitta in Nepal after nightfall. They couldn’t see much in the night because the Indian Army was posted at various spots along the border. Subedi called his father from the nearest hotel in Nepal; he told him to make his way over to a nearby refugee camp along with the other two men.

Shortly after they arrived, on March 29, police arrested the three men for illegally entering Nepal and took them to jail, where they remained for almost a month. His father, with the help of local advocates, filed a petition, and, almost a month later, a judge in Nepal ruled that they could be released while the court case progressed.

On June 20, authorities in Nepal announced their decision: Subedi and others would be deported — again. This time, to their “place of domicile,” explained Siwakoti, the Nepali human-rights advocate, which could be interpreted as Bhutan or the U.S., the two countries that had already deported these men months prior. The court also ruled that the men would also be fined 5,000 Nepali rupees each, along with $8 per day in fees for every day they had been in the country illegally (excluding the days they spent in detention). Nepalese authorities, currently in the midst of a tumultuous regime change, are not enforcing the deportation orders, so deportees have remained in refugee camps or in other temporary housing without status. But their cases aren’t priorities for resolution in court either, Siwakoti said.

Subedi has paid the fine, but he and his father are strained for money, particularly because they have been hosting some of the other men from the U.S. who came in subsequent rounds of deportation. One is staying with them at the moment. They have been asking advocates to help fund meal rations and tea through private donations — and often asking family members for help. It simply isn’t sustainable, Subedi said. “For how long will we keep saying, ‘Give me money, give me money,’” he said. “We lived there; we know how much everything in America costs.”

If they had wanted to punish him further for his crime, the authorities should have tacked on extra time to his sentence, Subedi said, instead of deporting him. He is losing hope that he will ever return. Waiting two-to-three years for the political winds in America to change feels like “a long time in this place,” he said. “By then, everyone will forget. I don’t think anyone will want to help us.”

From Intelligencer - Daily News, Politics, Business, and Tech via this RSS feed