The COP30 climate summit – held in the city of Belém, on the edge of the Amazon rainforest – saw the Brazilian presidency launch a new forest fund and promise a “roadmap” to put an end to deforestation.

Almost every country in the world signed off on a final COP30 package called the “global mutirão” – meaning “collective efforts” – after two weeks of talks ran into overtime amid deepening divisions, compromises and even a fire in the conference venue.

Countries also agreed on a set of indicators for countries to track their efforts on climate adaptation, including within the food and agriculture sectors.

Brazil’s much-anticipated tropical forest fund, launched just before COP30 officially began, raised $6.6bn, more than half of which will come from Norway and Germany.

In the second week of the negotiations, dozens of countries backed plans to agree on roadmaps to guide the move away from fossil fuels and deforestation.

Although these roadmaps did not make it into the final negotiated text, COP30 president André Corrêa do Lago said they will be developed outside the formal UN process.

The final mutirão text mentioned biodiversity loss, land rights and deforestation, but did not feature food – which disappointed some observers, including one expert who said food systems had been “erased” from COP30.

Meanwhile, the formal agriculture negotiations ended without a substantive outcome and talks are expected to continue next year.

Indigenous peoples featured strongly at COP30 and attended the summit in larger numbers than ever before. During the talks, $1.8bn was pledged for land rights and Brazil announced new Indigenous territories.

Below, Carbon Brief breaks down the main COP30 outcomes on food, forests, land and nature.

‘Global mutirão’AdaptationTropical Forest Forever Facility and other forest pledges Other forest fundsAgriculture and food securityArticle 6Deforestation roadmap

‘Unilateral trade measures’BiofuelsFood systems and waterClimate and nature ‘synergies’Indigenous representationMethaneAgricultural greenwashing

(See Carbon Brief’s coverage of key outcomes for food, forests, land and nature from COP29, COP28, COP27 and COP26.)

‘Global mutirão’

COP30 saw countries agree to a new “global mutirão” decision, a text calling for a tripling of adaptation finance by 2035 (later than some hoped), a new “Belem mission” to increase collective actions to cut emissions and – to the disappoint of many countries – no new “roadmaps” on transitioning away from fossil fuels and reversing deforestation. (See Carbon Brief’s snap analysis.)

“Mutirão” is a Portuguese word originating in the Indigenous Tupi-Guarani language that refers to people working together towards a common aim with a community spirit – something the COP30 presidency was keen to emphasise.

The presidency was also keen to stress that the mutirão text was not a cover text (sometimes referred to as a “cover decision”). However, like a cover text, it sought to bring together important issues that were not on the formal agenda with negotiated targets, acting as the key agreement from COP30.

The first draft of the mutirão put forward by the Brazilian presidency on 18 November included optional text to create a “high-level ministerial round table”, aimed at supporting countries to develop their own national roadmaps on transitioning away from fossil fuels and halting and reversing deforestation. (See: Deforestation roadmap.)

The language around this was criticised as weak by some observers, but its inclusion was widely welcomed.

Option two for paragraph 35 of the first draft of the mutirão decision, published on 18 November. Source: UNFCCC (2025)

The final mutirão decision did not mention fossil fuel or deforestation roadmaps. It did mention deforestation once, “emphasising” the importance of boosting efforts to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030 to help achieve the Paris temperature goal.

It noted that this is “in accordance with Article 5 of the Paris Agreement”, which is a section of the landmark climate deal that calls for strengthening of the world’s carbon sinks, including forests. (Carbon Brief understands that a large group of rainforest nations, called the Coalition of Rainforest Nations, were particularly keen to have Article 5 referenced in the final mutirão decision.)

The final text of the global mutirão decision, referencing aims to reverse deforestation and forest degradation by 2030. Source: UNFCCC (2025)

The final mutirão decision makes multiple brief mentions of nature and the need to tackle climate change and biodiversity loss in a synergistic way.

Paragraph two of the agreement, in the section sometimes called the “preamble”, “emphasises” the importance of “conserving, protecting and restoring nature and ecosystem”.

Further down, in a section “recalling” the first global stocktake of climate action conducted at COP28 in Dubai in 2023, the text “underlines” the “urgent need to address, in a comprehensive and synergetic manner, the interlinked global crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, and land and ocean degradation in the broader context of achieving sustainable development”.

This inclusion likely reflects the presidency’s keenness to prioritise “synergies” between climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation. (See: Climate and nature ‘synergies’.)

While the mutirão text included references to safeguarding Indigenous rights, conserving biodiversity and maintaining nature-based stores of carbon, no mention of food or agriculture appeared in any draft of the text.

Prof Raj Patel, a member of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food), said in a statement that it was as if food systems were “erased” from the negotiations, adding:

“Two years ago, 160 countries signed a Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture with great ceremony. Today, they cannot bring themselves to mention the word ‘food’ in the mutirão decision.”

Adaptation

One of the major negotiated outcomes of the Belém summit was the agreement of a set of indicators for countries to measure their progress towards the global goal on adaptation (GGA).

The GGA, agreed at COP28 in Dubai, sets out 10 targets for countries to measure their progress towards, including targets on water scarcity, climate-resilient food systems and reducing climate impacts on ecosystems.

The initial list of indicators for these targets numbered 10,000. These had been whittled down by experts since COP28 and, at COP30, negotiators were tasked with agreeing on just 100 for countries to use.

Divisions were apparent from the first day of COP30, with the African group and Arab group proposing a two-year period for refining the GGA indicators before formally adopting them in 2027, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin. This move was opposed by several other blocs, including the Independent Alliance of Latin America and the Caribbean (AILAC) and the EU.

Disagreements arose between countries on the need for finance in order to implement the GGA, whether indicators infringed on countries’ sovereignty and indicators around domestic financing.

Richard Muyungi, African group chair, told Carbon Brief in the first week:

“We need to put guardrails or caveats on the adoption [of the indicators]. For example…the indicators should not infringe on the sovereignty of countries, asking countries to change their laws, their strategies. I mean, you cannot ask my country to change laws, because they want to address the global goal.”

Ultimately, countries adopted a set of 59 indicators and agreed to a two-year work programme “aimed at developing guidance for operationalising the Belém adaptation indicators”.

The set included five indicators on assessing progress towards climate-resilient and sustainable food systems.

Indicators assessing food systems and agriculture within the final GGA text. Source: UNFCCC (2025)

The indicators on ecosystems and biodiversity included measuring the proportion of ecosystems “providing services to populations that depend on them”, the level of adaptive capacity due to the implementation of nature-based solutions and the levels of threat status of ecosystems and species.

However, observers noted that the indicators were heavily caveated, with the introductory text of the agreement “emphasis[ing]” their voluntary nature.

Introductory text from the GGA text agreed at COP30, emphasising the voluntary and non-binding nature of the indicators. Source: UNFCCC (2025).

(For more on adaptation and the GGA, see Carbon Brief’s explainer of COP30’s key outcomes.)

Tropical Forest Forever Facility and other forest pledges

At the COP30 leaders’ summit, Brazil officially launched the Tropical Forest Forever Fund to “reward” countries that conserve their tropical forests.

During the negotiations, the facility raised $6.6bn and had the support of 53 countries, including countries with tropical forests and those that will act as investors.

This instrument is intended to be a financial vehicle to raise $125bn from countries, philanthropy and private investors, which will then be invested in the global bond market. It is intended to be able to support up to 74 countries that have tropical forests across many regions, such as the Amazon and the Congo Basin.

The TFFF has been described as “the largest forest-finance mechanism ever created” and praised by Brazil’s finance minister, Fernando Haddad, as “innovative” for combining public and private financing.

However, it has also received criticism.

As Carbon Brief has previously reported, experts have concerns around fragmenting existing climate finance and inadequate accountability. Other criticisms have focused on worries that the fund could benefit investors over forest countries and that 20% of the funds being directed to Indigenous peoples is insufficient.

For Sandra Guzmán, founder and general director of the Climate Finance Group for Latin America and the Caribbean (GFLAC), the Brazilian government focused on moving forward with the TFFF and neglected other aspects of financing, such as the Baku to Belém roadmap to mobilise $1.3tn per year in climate finance by 2035. She told Carbon Brief:

“The TFFF is not a mechanism that has been agreed upon multilaterally. [If the fund fails in its mission], it would only confirm that Brazil could have [capitalised] on other funds that are within the [UN climate] convention and do have a future.”

After the launch of the TFFF, it was rejected by 150 civil society groups and Indigenous peoples’ organisations, who said the fund “does not seek to address the true structural causes of forest destruction” and “does not prioritise Indigenous peoples and local communities”.

The COP30 presidency stated that, in the second week of negotiations, governments, multilateral funds and Indigenous leaders met to discuss how an Indigenous governance model – known as Dedicated Grant Mechanism (DGM) – can “inform and strengthen the emerging generation of climate finance facilities”.

Analysis by the civil society organisation Leave it in the Ground (LINGO), presented at COP30, suggested that not extracting fossil fuels beneath forests eligible for the TFFF would prevent 4.6tn tonnes of CO2 from being released.

These emissions would be saved if countries “were to adopt a pledge of no fossil-fuel extraction in its forests”, the report said.

Kjell Kǘhne, director of LINGO, said in a press conference attended by Carbon Brief that while restrictions on fossil fuels are not part of the scope of the discussions of the TFFF, this would make it “even stronger”.

Other forest funds

Elsewhere at COP30, countries renewed their COP26 commitment to help protect rainforests in the Congo Basin, which contains the world’s second-largest area of tropical forest. A Belém “call to action” pledged to raise more than $2.5bn for the cause over the next five years. This was put forward by Gabon and France and signed by Germany, Belgium, Norway and the UK, alongside development banks and other groups.

A new pledge of $1.8bn was put forward from more than 35 governments and philanthropic organisations to help secure land rights across forests and other ecosystems for Indigenous peoples, local communities and Afro-descendent communities, according to the Forest & Climate Leaders’ Partnership. (See: Indigenous representation.)

The UK also announced almost £17m in funding for the Accelerating Innovative Monitoring for Forests (AIM4Forests) programme, a cooperation between the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the UK that supports countries in monitoring and reporting on forests.

Meanwhile, Brazilian development bank BNDES approved R$250m (£35m) for ecological restoration and tree-management projects in parts of the Amazon and Atlantic forests, Brazilian outlet InfoMoney reported, adding that the funding will help to recover up to 19,000 hectares of forest land.

On 17 November, when forests featured as one of the COP30 themes of the day, more than 70 civil-society groups called on governments to set up forest “fossil-free zones” – areas where oil, coal and gas are not extracted – to protect forests and the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities.

Earlier that week, Colombia said it was the first Amazonian nation to keep its entire Amazon forest area “free from oil and mining activities”, InfoAmazonia reported.

Countries that hold the Amazon rainforest, including Brazil, Peru and Colombia, also launched an initiative, called Amazonia Forever, to gather more than $1bn to invest in Amazonian infrastructure and cities.

Brazil’s planning and budget minister, Simone Tebet, said this programme for cities and resilient infrastructure would “enable us to take action not only on forest and water resources, but also on urban challenges”.

Agriculture and food security

With agribusiness giant Brazil hosting this year’s summit, many expected COP30 to have a stronger focus on agriculture and food than previous years.

Formal negotiations for agriculture and food systems under the UN climate convention fall under the Sharm el-Sheikh joint work on the implementation of climate action on agriculture and food security (SJWA). COP30 ended without a substantive outcome for the SJWA.

The current four-year mandate of SJWA – which runs workshops, is developing an online portal and prepares an annual synthesis report of agriculture-relevant work undertaken by UN climate convention bodies – began in 2022 and runs out at COP31 next year.

At COP30, the main points of discussion for countries were a consideration of the outcomes of a workshop on “systemic and holistic approaches” to implementing climate action on food and agriculture, as well as countries weighing in on a special forum of the standing committee on finance (SCF) on financing for sustainable food systems and agriculture.

As the summit got underway in Belém, several parties began pushing the idea of capturing key messages from the workshop and forum into a formal SJWA decision.

Observers told Carbon Brief that Argentina, the African group and the least-developed countries (LDCs) wanted “means of implementation” – shorthand for finance – added to the text, while the EU opposed references to “Article 9.1” in the agriculture workstream. (See: Climate finance in Carbon Brief’s main COP30 outcomes piece.)

Draft text on agriculture negotiations published on 13 November, with references to means of implementation. Credit: UNFCCC (2025)

The next day, various blocs circulated text proposals on recognising the workshop outcome. These texts, seen by Carbon Brief, included proposals from the EU and the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG) on food systems “which span the entire value chain”, links to biodiversity, “precision agriculture” and market-based rewards for farmers.

G77 and China, meanwhile, flagged 13 points for inclusion in the draft text, including recognising the “fundamental priority of ending hunger” and a call for developed countries to “significantly scale up…grant-based finance for adaptation actions in agriculture”.

Language from all of these proposals was incorporated into a draft text released on the first Thursday of COP30.

This draft – with 23 square brackets, indicating text not yet agreed – included many references, ranging from agroecology to AI-farming and using “high-integrity carbon-market approaches under Article 6” to reward farmers.

It also recognised that the World Trade Organization (WTO) “can be useful in ensuring a stable, predictable global agricultural trade underpinned by rules” that support climate action.

Sections from a 13 November draft text incorporating blocs’ divergent views on “holistic approaches” to climate action in agriculture. Source: UNFCCC (2025)

Five hours later, this was replaced by a brief draft, which postponed further discussions until June next year, taking into account the earlier text.

The draft text published on the evening of 13 November, with countries agreeing to conclude agricultural negotiations under SJWA at COP30. Source: UNFCCC (2025).

Many observers expressed their dismay at negotiations finishing so abruptly, before the end of week one and without a substantive outcome.

Teresa Anderson, global climate justice lead at Action Aid International, told Carbon Brief that negotiations “took a turn for the worse” after Australia and the EIG “pushed for dodgy language” on what could be considered “systemic” and “holistic”. Anderson said:

“In June, many countries talked about agroecology. And yet here in the COP, Australia and others just submitted language on precision agriculture, on AI and just basically a lot of corporate greenwash…Countries weren’t able to agree on [this] because there was just too much new nonsense in there.”

The final draft conclusions “recognised that progress was made at these sessions” and “noted that more time is needed to conclude the discussions thereon”.

Article 6

Carbon markets – particularly relating to forests – were expected to be a key priority for the Brazilian presidency at COP30.

On 7 November, the Brazilian presidency launched a global coalition on “compliance carbon markets”, endorsed by 18 countries.

The voluntary initiative said it is designed to allow members to “share experiences and learn from each other”. It also said the coalition will “explore options to promote interoperability of compliance carbon markets in the long term”.

Finally, it mentioned information exchange on the “potential use of high-integrity offsets”, referencing a sector that has faced intense scrutiny in recent years.

The same day, Honduras and Suriname announced a deal to issue “high-integrity rainforest carbon credits” in partnership with Deutsche Bank, German agrochemical giant Bayer and the Coalition for Rainforest Nations (CfRN).

An action outside the COP30 venue on 11 November, resisting what activists called a “carbon casino” at the climate talks. Credit: Bianka Csenki, Artivist Network (2025).

Formal negotiations on carbon trading under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement were expected to be somewhat muted, but ended up being rather complicated.

In Baku last year, countries had finally agreed on the rules for country-to-country carbon trading under Article 6.2 and for a new international Paris Agreement carbon market under Article 6.4, bringing a decade of negotiations to a close. Countries also agreed to undertake a review of these rules in 2028.

Within the Article 6.4 market, key tools for “nature-based” removals and rights safeguards were still being developed after COP29 by the “supervisory body” in charge of standards.

At COP30, negotiations focused on the annual report of this body, which had been given autonomy to set these standards at COP29.

The supervisory body had recently adopted a standard on non-permanence on 10 October, which had been the subject of heated debate in the sector.

The standard describes how to handle the risk of someone selling carbon credits for a project that removes CO2 from the atmosphere, only for this stored carbon to be released back into the atmosphere. This is a phenomenon known as “reversal” and is particularly pertinent for tree-planting projects, which may be at risk from wildfires and drought.

In a joint letter published on 12 November, a group of NGOs and carbon-trading advocates said this and other standards “could exclude all land-based activities”, such as forests, from the Article 6.4 market.

They called for new guidance to be given to the supervisory body to prevent this from happening. Their recommendations on amending the rules around reversal risk to give more scope to include nature-based projects – which were opposed by some scientists and other NGOs – were picked up and reflected in an early draft text at COP30.

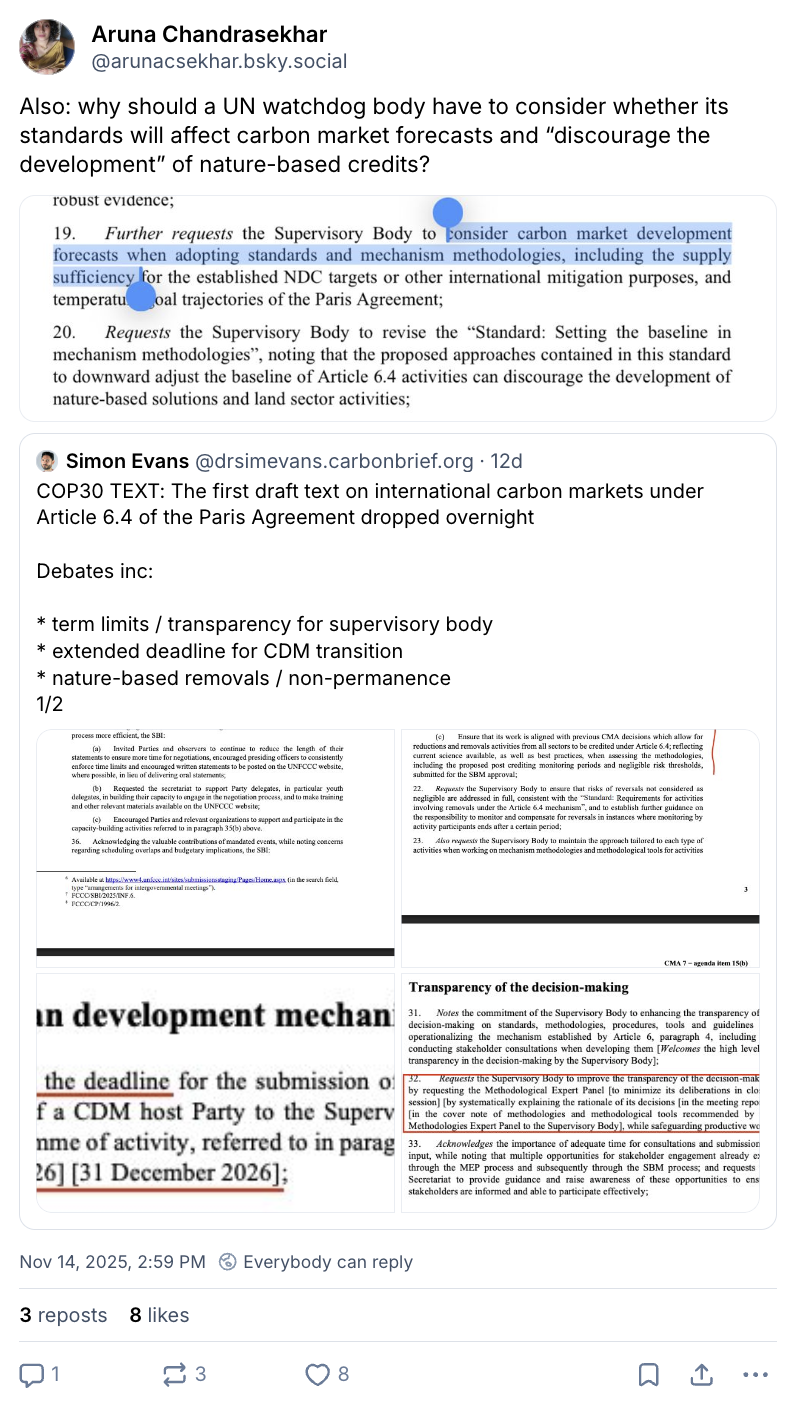

This text, published on 14 November, asked the market’s supervisory body to “consider carbon market forecasts” and revise its standards so as not to “discourage the development” of nature-based solutions.

At the same time, text options “urging” the body to make its decisions more transparent and “minimise time in closed-door sessions” were heavily bracketed.

The first draft text on Article 6.4 carbon markets had several references to nature-based solutions and approaches, calling for flexibility from the supervisory body in applying its standards to them. Source: UNFCCC (2025)

In response to this draft text, Isa Mulder of Carbon Market Watch told Carbon Brief:

“All of the pro-market flexibility in there [would] completely undermin[e] the Paris Agreement.”

On 15 November, Climate Action Network awarded Indonesia its “Fossil of the Day” for repeating “lobbyists’ talking points” surrounding weaker rules on the permanence of nature-based credits – “sometimes verbatim” – in its intervention in Article 6.4 negotiations.

While explicit references to nature and nature-based carbon crediting projects were removed in a second draft issued late on 15 November, the text still asked the body to apply a “tailored approach” and weigh the “economic feasibility” of its standards.

In the end, references to these two terms were also dropped. Many countries saw the effort to give detailed guidance to the supervisory body as an attempt to “micro-manage” its work, creating uncertainty for market actors.

The final decision on Article 6.4 gave carbon-credit projects registered under the “clean development mechanism” (CDM) a six-month deadline extension, until June 2026, to “transition” into the Paris Agreement’s new carbon market.

In theory, this could allow up to another 760m tonnes of CO2-equivalent of credits to enter the Paris Agreement regime.

The final Article 6.4 decision “averted disaster” and could potentially make the UN-backed carbon market “marginally” more inclusive, according to Carbon Market Watch, which added that these improvements “do little to change the rather worrying course that Article 6 seems to be on”.

The decision “reiterates” that supervisory body members should not have “any financial or other interests” that could affect – or be seen to affect – their impartiality.

It also “requests” that the body strengthen its consultation processes by informing, reaching out to and including Indigenous peoples, local communities and others who “cannot easily participate” in the complex mechanism.

The final COP30 decision on Article 6.4 calls for the UN-backed carbon market’s autonomous body to include Indigenous peoples in its consultations. Source: UNFCCC (2025)

While there are fewer rules that govern country-to-country carbon trading under Article 6.2, countries were supposed to submit “initial reports” of these bilateral carbon-trading deals for review by technical experts ahead of COP30.

The first six reviews – including a Swiss-supported project to promote “climate-smart” rice cultivation in Ghana and sustainable forest management in Guyana and Suriname – were completed ahead of the summit.

A particular issue being considered at COP30 was the fact that, to date, “all trades” under Article 6.2 so far have been flagged with “inconsistencies” during expert review.

The COP30 Article 6.2 decision simply “notes” these inconsistencies and “urges” countries to sort them out, while adding that the reporting and review process is still “in the early stages”. It also asks reviewers to “clearly explain” any issues they find and how to resolve them.

[Content truncated due to length…]

From Carbon Brief via this RSS feed