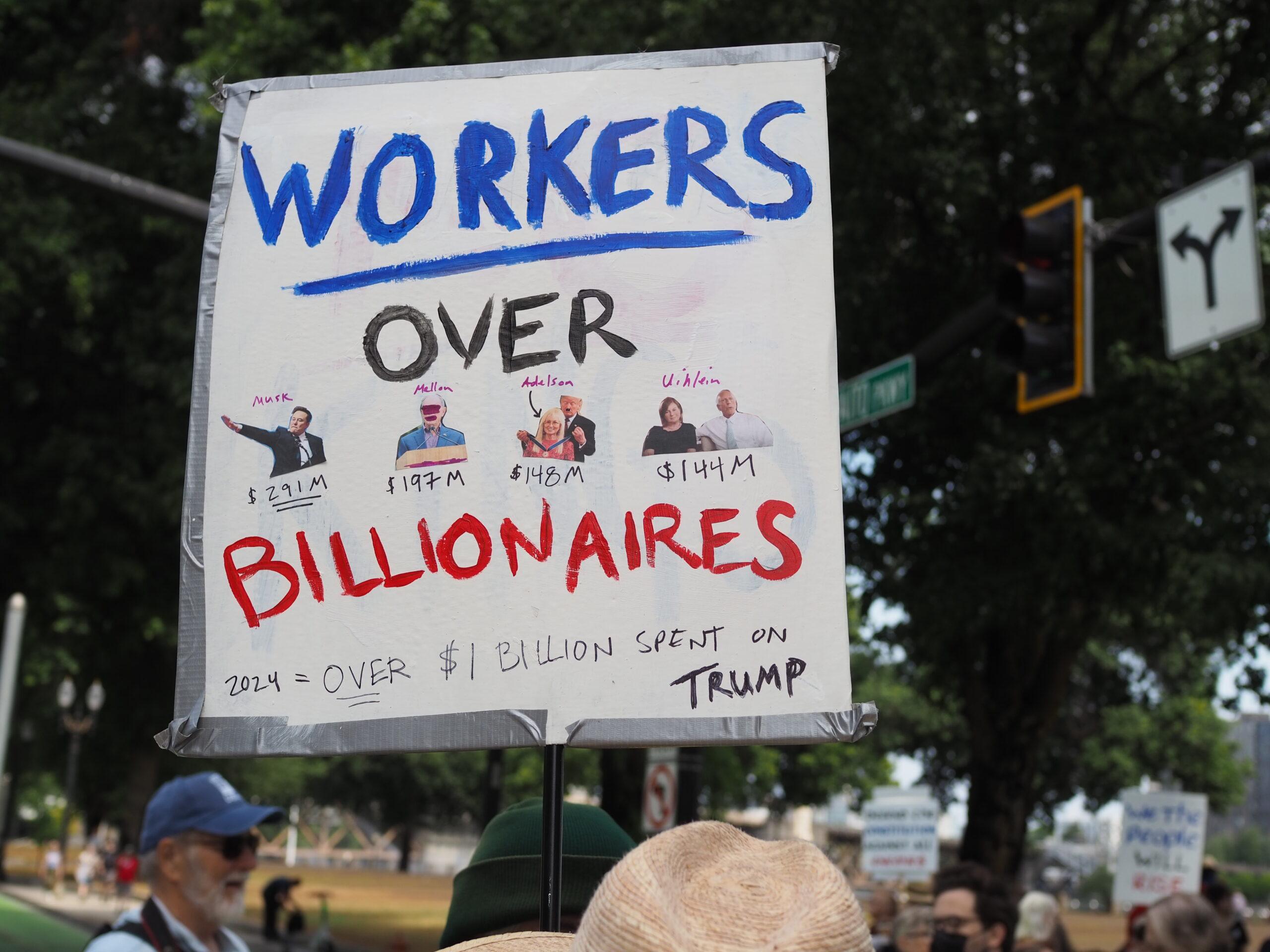

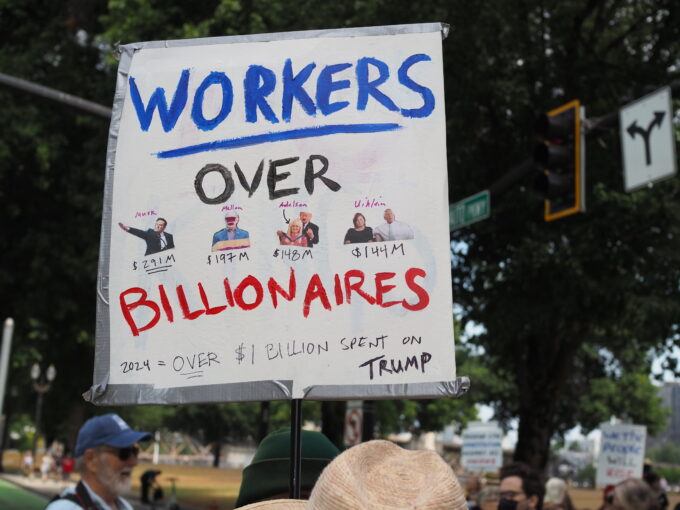

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

“If poor people knew how rich rich people are,” Chris Rock once quipped, “there would be riots in the streets.”

So, I wonder, what would average taxpayers do if they knew they’re currently paying income tax at triple the rate our richest megabillionaires are paying?

Few taxpayers understand this reality, largely because of how we’ve been conditioned to contemplate “income” and “income tax.” Every year we follow the same routine. To tally up our income for tax purposes, we take the wages from our paychecks, add in a little of this and that, and end up arriving at what the tax code defines as our “adjusted gross income.” That becomes our reference point for “income” in our daily lives.

But lots of income — in a real-life economic sense — doesn’t land on our tax returns, at least not in the year it’s generated, and often not even ever. Those modest increases in the value of our homes over the course of a year? We don’t generally think of those increases as income, but they do rate as such. And these modest annual increases in home values that average taxpayers see pale against the rising asset values that our richest billionaires see, rising asset values that show up nowhere on their tax returns.

To understand how absurdly undertaxed our megabillionaires have become, we need to start with the income-defining work of two economists active and honored about a century ago, Robert Haig and Henry Simons. Haig and Simons developed a concept for defining a person’s true annual income now referred to as “Haig-Simons income.”

A person’s Haig-Simons income over a year would be that individual’s wealth at the end of the year reduced by the individual’s wealth at the beginning of the year, plus the amount spent on consumption during the year. Put another way, a person’s Haig-Simons annual income would be the amount a person’s wealth would have increased over the course of a year if the person did not reduce that wealth through spending.

Why do we need to bother with Haig-Simons calculations? We have an exceptionally good reason: How we tax the Haig-Simons income of our richest Americans determines our national level of wealth inequality!

A recent report from economists at the University of California-Berkeley sheds new light on this dynamic. In the years 2018 to 2020, according to this report, average American taxpayers ended up annually paying about 14.6 percent of their Haig-Simons income in individual income and payroll taxes. That total included federal, state, and local income taxes as well as withholding from wages for Social Security and Medicare taxes.

For high income taxpayers, the total also included something known as the “net investment income tax,” an additional tax on investment income for those with incomes over $250,000 in a year.

Treating all these taxes as “income” taxes makes eminent sense because, well, that’s what they are: taxes on income.

How much of income defined this way did taxpayers in our wealthiest .00005 percent pay in individual income taxes from 2018 through 2020? These awesomely affluent — roughly, America’s richest 100 — paid only 7.1 percent of their Haig-Simons income per year in taxes. They paid taxes at less than half the rate average American taxpayers paid, on income roughly 10,000 times greater than average taxpayer income.

That reality not obscene enough for you? Consider this: A sizable portion of the 7.1 percent of Haig-Simons income that our megabillionaires pay in income tax amounts to “tax” in name only. The “tax” they pay actually amounts to an interest expense. Factor that reality in and the ridiculously low 7.1 percent tax rate the average top 100 billionaire pays shrinks to an even more ridiculously low 5 percent.

A bit more detail can help us understand why.

We can tell from the types of income top 100 billionaires report on their tax returns — and the amount of income tax they pay — that about 68 percent of their income tax payments reflect long-term capital gains. Of that 7.1 percent of Haig-Simons income that top billionaires pay in individual income tax, about 4.8 percentage points represent tax payments on long-term capital gains.

Here we encounter another misconception about income tax payments. Most all reporting on tax payments, the Berkeley economist study included, makes no distinction between income tax paid on gains that accrued over many years and income tax paid on wages and other income generated in the year of payment. In other words, in comparing the income tax payments of average Americans to those of the ultra-wealthy, the available data allow only for an apples-to-oranges comparison.

Taking this approach — treating the tax payments our top billionaires make on their capital gains the same, dollar-for-dollar, as the tax payments average Americans make on their annual income — ends up being wildly misleading because precious little of top-billionaire tax payments relates to income generated during the current year. These payments, nominally labeled as “tax” payments, function — in an economic sense — as payments for the privilege of deferring the payment of tax on income from prior years.

We should consider these payments, in other words, to be part tax and part interest expense.

Average Americans, of course, can also claim long-term capital gains. But the income tax average Americans pay on capital gains represents just a tiny portion of their total income and payroll tax liability. For them, the portion of tax they pay as the economic equivalent of interest expense adds up to no more than a rounding error.

And what portion of the nominal tax payments of our ultra-billionaires boils down to disguised interest expense? A quite large one, it turns out.

Consider a $1-million stock investment that grows in value at a rate of 15 percent per year for 20 years, reaching a value of $16.37 million, at which point our ultra-billionaire sells the asset. Our billionaire would be left with just over $12.7 million after paying a tax of about $3.66 million on the $15.37-million gain.

That would be the same gain our billionaire would see if the billionaire had paid income tax at a rate of just 9.63 percent per year on the annual gains, assuming the billionaire sold just enough stock each year to pay the tax. But the sum of those annual payments would be just $1.25 million, barely a third of the $3.66 million one-time tax the billionaire paid upon the sale of the investment.

We can consider the $2.41-million difference between those two figures as, in substance, interest, the charge incurred for the privilege of delaying payment of income tax until the sale of the investment. The basic math here: If we reduce that $15.37 million gain by the $2.41 million interest expense, we have a net gain, after interest expense, of $12.96 million. The tax on $12.96 million at a 9.63 percent rate — the portion of the $3.66 million tax payment that is truly tax — comes in at $1.25 million.

An asset that grows in value at 15 percent per year for 20 years would be a stupendous investment for the average American. But for our richest billionaires, that gain would rate as at best just so-so. Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway shares have increased about 20 percent per year for the past half-century. A share of Nvidia stock, worth about $200 today, carried a 4-cent value in January 1999. Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s co-founder, owns over 800 million of those shares. He has seen each share increase in value at an average annual rate of 37 percent over the past 27 years. Jeff Bezos’ remaining $200 billion of Amazon stock has averaged an annual gain of over 50 percent since 1994.

Bezos, when he sells a share of his Amazon stock, pays a 23.8 percent tax on the gains he pockets. But his actual windfall at tax time will run much higher than the windfall for our billionaire above with a $1 million investment that grew in value at a rate of 15 percent per year for 20 years. The true tax rate that Bezos enjoys, after calculating the true interest he has been paying for the privilege of delaying payment of income tax until he sells his investment, comes to a minuscule 2.45 percent.

Now suppose that only half the nominal tax our top billionaires pay on their investment gains represents the economic equivalent of interest. That would reduce the tax rate on their Haig-Simons income to less than 5 percent, about one-third of the 14.6 percent rate the rest of us pay.

Should we be outraged? Hell yes. Should we ever cast a vote for a candidate who doesn’t promise to at least triple the real income tax rate on America’s mega-billionaires? Hell no.

The post Be Outraged: Your True Income Tax Rate May be Triple the Rate the Richest Billionaires Pay appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed