The Death of English Literature

(This essay, my review of Stefan Collini’s book Literature and Learning: A History of English Studies in Britain*, originally appeared in the New Statesman here. It is republished in Cultural Capital with their generous permission.*)

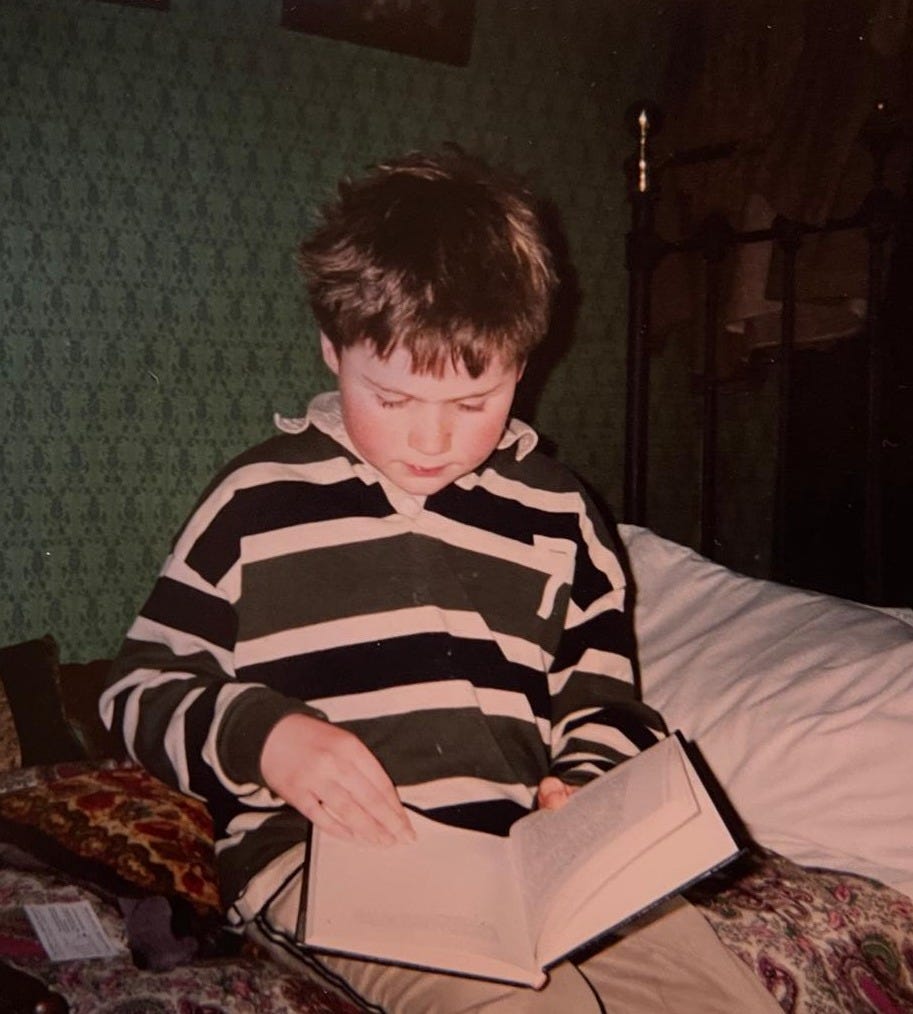

English Literature — so it seemed to me when I was a bookish zealot of eighteen — was the prince of the humanities. When I was interviewed at university and asked why exactly I wanted to study English, I informed my interrogators (I still remember the phrase which I had practised beforehand and considered richly impressive) that “literature shows us what it is or might be to be human”. I believed it.

In books, I felt with Tennyson, that I had sensed the living souls of the dead flashed on mine. Poems — especially poems by Hopkins, Eliot and Auden — worked on me like spells. I had contrived to download a recording of Auden’s Museé des Beaux Arts onto my primitive mobile phone, and would stand in the playground with the device pressed to my ear, enraptured by the tinny incantation, convinced I was responding to a higher call. Literature, if one were to reduce it to anything so tawdry as a formula, was history x philosophy x life. I regarded my peers who had chosen to study mere facts at university rather than to be inducted into the glamorous mysteries of the human heart with some pity (an attitude I have still not entirely shaken off).

English, as Stefan Collini observes in his wry and compendious new history of the discipline, Literature and Learning, tends to inspire an extravagant attachment rarely associated with “say, Geography or Chemistry.” Half the labour of writing a history of English must lie in gathering encomia to the subject by its disciples. To the moneyed amateurs who ushered the subject into universities at the beginning of the twentieth century (men who fondled poems like antique clocks and ranked novelists like vintages of claret) the study of literature was “a glory of the universe” or “the spring which unlocks the hidden life”. To the charismatic Leavisite secondary school teachers of the 1960s it was a moral crusade against the spirit-killing incursions of machine civilisation: English had “life-enhancing powers” and its study was essential if a modern person hoped to retain “any capacity for a humane existence”.

The scholarly Collini winces fastidiously at some of these “soaring affirmations”. And indeed, such confident panegyrics read oddly in an age when the subject is cowed, apologetic and shrinking. Nowadays, English is reduced to doing its pathetic, blundering best to ape the sciences, devising spurious jargons for itself, grinding scholars through the Research Excellence Framework and promising students “transferable skills” (that mad but unkillable doctrine beloved of prospectus-writers which holds that a familiarity with ecocritical perspectives on early Shelley is useful preparation for making powerpoints at PWC).

But for all the Gradgrindian propaganda embattled modern departments are obliged to turn out in the forlorn hope of attracting students, it remains the case that it is only because people have felt extravagantly about books that English is taught at universities at all. The subject remains an academic anomaly, a scholarly discipline premised on the acquisition not of knowledge but of aesthetic experience; on the unlikely marriage of (in Collini’s happy phrase) “beauty and the footnote”.

Students of English do not expect to emerge from their degrees able to speak a foreign language (save perhaps a smattering of Anglo Saxon) or code or say anything useful about the differences between arthropods and crustaceans. According to the purest conception of the subject, Collini points out, “the ur-exam question should be something like ‘isn’t this beautiful?’” Though surely, “the way to get high marks would not simply be to answer ‘Yes, it is.’”

This has been the source of English’s insecurity as an academic discipline — couldn’t an enthusiasm for Keats be better satisfied in a student’s spare time? — but also its self-confidence as the purest and most noble of the humanities.

Dove Cottage

I was a late product of this passionate tradition. My English teacher father brought me up to regard Eng Lit as a secular religion. Our God was Shakespeare whose birthday we celebrated annually with a home-made cake. Like Catholic peasants our house was strewn with tasteless devotional items: Shakespeare mugs, Shakespeare socks, Shakespeare tea towels, a Shakespeare bear (clad in a t-shirt featuring a quotation from Hamlet). We quoted Shakespeare, and his attendant lesser deities Wordsworth, Tennyson and Milton like scripture. And in the summer holidays we made solemn pilgrimages to their shrines: Dove Cottage, The Globe Theatre, Stratford upon Avon.

My father particularly impressed me with the information that a friend of his had once repelled a home invader by descending the staircase in the dark carrying a single lighted candle and intoning a sulphurous passage from Book One of Paradise Lost. Such — the moral of the story ran — was the power of blank verse. (I have never quite lost the conviction that should I ever find myself in similar danger the Collected Milton, rather than, say, a hammer, is the weapon I will need to have to hand.)

If the atmosphere of militant Bardolatry in which I was raised was anachronistic in the early 2000s it seems as archaic as Assyria now. English is in precipitous decline. Still the most popular A-level subject when I left school in 2011, it no longer even makes the top ten, having been displaced by various STEM subjects and those vulgar parvenus, sociology and psychology. Another university English department shuts down practically every year.

My friends who pursued academic careers in English — no more apocalyptically disillusioned class of person exists — feel they are heirs to a ruined inheritance. They were preparing to take possession of great mansions of learning but find the windows have been smashed, the furniture looted and the electricity cut off. Partly the problem is tuition fees — £9,535 per year to acquire a finer appreciation of moon imagery in DH Lawrence is a hefty ask in the present economic climate. But most importantly, literature is becoming culturally marginal. The screen is replacing the book. Studies show dramatic and unprecedented drops in literacy and reading, especially among teenagers. A recent survey by the National Literacy Trust found time spent reading books “at a historic low”.

In this environment, the study of literature is far from an obvious use of three crucial years of young adulthood. And if the slew of viral journalistic reports from universities — “The End of the English Major”, “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books” — are to be believed, even students who choose to study English are unable to actually force themselves through novels. “Most of our students are functionally illiterate” runs a characteristic de profundis wail. A young Oxbridge academic I spoke to recently described “a collapse of literacy” among his students.

The first enemies of English worried not that reading novels was too hard for students, but that it was much too easy. When English arrived in universities (at Oxford in 1894 and Cambridge in 1914) conservative dons objected that the subject wouldn’t provide students with “the mental training” inculcated by Mathematics or Classics (Greek, according to one doggedly unenlightened strand of opinion was “a kind of maths without numbers”). Others feared that English was an invitation to students to be “specious and superficial” (the suspicion has never quite been dispelled). Why did you need educating in how to read poems?

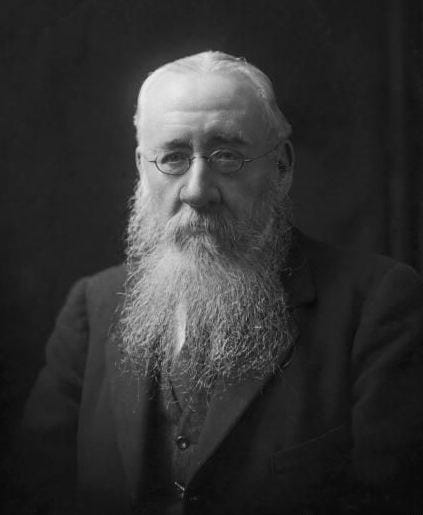

The literary gentlemen who were first summoned from the clan warfare of Grub Street to establish English amidst the Groves of Academe were not always reassuring models of scholarly rigour. Cambridge’s first Professor of English Arthur Quiller Couch was in the habit of addressing his audiences of mostly female undergraduates as “Gentlemen!” George Saintsbury, the king of fin-de-siecle belles lettres — with his wine cellar, “extreme Toryism”, prodigious forest of a beard and apparently omniscient command of his country’s literary heritage — was making £190,000 a year in modern money from literary journalism before he was made a don (his earnings were much enhanced by his genial willingness to review the same volume “as many as five times”). His own innumerable books, (Elizabethan Literature, Nineteenth Century Literature, The History of English Prosody from the Twelfth Century to the Present Day, an 800-page Short History of English Literature) combined panoptic ambition with “a large number of errors” and sold in the tens of thousands.

George Saintsbury

Saintsbury’s career was only an unusually florid symptom of a society in which English literature was culturally central to a degree not easy to grasp today and which throws a stark light on the subject’s present crisis of marginality. English was born as an academic subject in a world in which journals and magazines “carried an endless stream of critical essays celebrating or reconsidering the achievement of major and minor poets alike”. For many people “a deep intimacy with English poetry was a living presence, not simply a social affectation or a relic of a half-remembered education”.

The critic AC Bradley was the subject of doggerel in Punch and his book Shakespeare’s Tragedies went on to sell half a million copies. When the socialite turned don John Bailey gave public lectures (“Can We Tell Good Books from Bad”, “Shelley”) he addressed “crowded” halls of hundreds of people (“many standing”) and met with “wild success”. When he lunched with the former Prime Minister Arthur Balfour in 1914, the two men chatted about “Dryden, Pope, Browning, etc.” Bailey and his wife habitually recited Browning to one another over dinner, after which he would go upstairs to read his children their bedtime story: Edmund Spencer’s The Faerie Queene.

The apogee of Eng Lit’s prestige arrived in the “two decades after 1945”. Students streamed through the red brick portals of Manchester and across the alien concrete geometries of York for lectures on “Shakespeare and his Contemporaries”, “Milton and the Seventeenth Century”, and “The English Augustans”. By this time, the subject had been refashioned as a modern, professional discipline. To IA Richards, the father of practical criticism, the study of literature was a laboratory science (the text carefully tweezered and isolated beneath the critic’s microscope); to FR Leavis, it was a kind of non-conformist religion. The prevailing tone of high moral seriousness — “a spiritual exploration coterminous with the fate of civilization itself”, as Terry Eagleton once summarised the Leavisite view of literary studies — charged English with a charisma that no other academic discipline has ever matched, either before or since.

The University of York in the 1960s

Academic critics became celebrities and for a while, the culture bowed to them. The position of English at this time strikes modern readers as almost comically exalted. “It is no exaggeration to say”, writes one historian quoted by Collini, “that in the late 40s and early 50s, for the hippest of the young (even among those who were beginning to be beat) the best thing in the world to be was T.S. Eliot or Edmund Wilson. Literary criticism was the philosophers’ stone”. In the USA in the 1950s it was possible to watch “a regular TV programme featuring Lionel Trilling, Jacques Barzun, and W.H. Auden”. And in a lecture, Trilling went so far as to fret that “the place literature occupies in contemporary life is ‘actually too high’” and that its study attracted “disproportionate” numbers of students — not anxieties that much trouble modern professors of English.

At this time English derived energy and confidence from its practitioners’ sense of themselves as cultural insurgents, partisans of intelligence and humane values fighting a guerilla war against the stupefying and ominously expanding empire of mass culture, what Richards called the “sinister potentialities of the cinema and the loud-speaker”. Leavis was the movement’s Castro, prolix, repetitive and superannuated, thundering away against the evils of television. His hostility was influential. “The very power to resist and question the mass media, or the misuse of technology, derives from our ability to transmit the best of the past”, urged one teachers’ handbook. English by wide consent, was “the civilising, maturing subject”.

Recent academic commentators have been nervous of these painfully un-groovy defences of standards. In the complacent fastnesses of Oxford and Cambridge the idea that such frivolous technologies as the television or the cinema might pose a threat to the grand enterprise of literature was worthy only of a raised faux-worldly eyebrow. But Leavis’s perception that the new forms of electronic entertainment demanded “surrender, under conditions of hypnotic receptivity to the cheapest emotional appeals” is hard to read without foreboding in the days of TikTok. Such warnings once read as so much rhetorical thunder and lightning; today they read like prophecy.

The battle against the hypnotising and stupefying forces of electronic entertainment has been definitively lost. The partisans have been routed. George Eliot was no match for the iPhone. The civilisation of the book has given way to the civilisation of the screen. English, in the view of one friend who teaches it at a university is, “not dying, it’s dead” — an incidental and probably unnoticed drive-by casualty of the Californian billionaires’ imperial campaign to annex our attention for their profit.

“In time,” Collini writes, “it may become possible to be accepted as a cultivated person (whatever that archaic term will by then have come to represent) without having an acquaintance with any literature written before one’s own era, or perhaps with any literature at all.” I agree but with one qualification … “May become possible?” To anybody under forty it is clear that time is already upon us. Whether this heralds catastrophe — whether the fate of literature indeed turns out to be coterminous with the fate of civilisation — remains to be seen.

When those of us raised in the faith survey the darkness of the modern world, the thought is a hard one to avoid

.

From Cultural Capital via this RSS feed