Photograph Source: Voice of America – Public Domain

The persistent rumours that imprisoned Pakistani politician Imran Khan is dead have been crackling away like Lahore firecrackers these past few weeks. They feel less like revelations than the arrival of something long predicted. Or are they just the manifestations of an over-inventive public and mistrusted military?

Khan, if still alive, has come to resemble Julian Assange when Assange was in confinement. He is not so much an Assange-like selfless warrior as a nonetheless remarkable human being living only a parallel existence to the rest of us. He has become, in the public imagination at least, a man shimmering darkly from his prison cell like a character in a gothic novel.

And to think that Imran Khan was remarkable even before politics propelled him into this other light—now darkness—of a country that never seems truly at ease with itself. Remember, Pakistan emerged through a combination of Jinnah’s political leadership, British colonial decision-making, and the wider politics of Indian nationalism, communal angst, and the snuffing out of empire.

Imran Khan—at the risk of this sounding like his obituary—was born into an affluent Pashtun family in Lahore’s well-heeled Zaman Park. This was 73 years ago. He attended the city’s exclusive Aitchison College, then the Royal Grammar School in Worcester, England. According to one former English schoolfriend, Khan was big on South Asian music as well as cricket: “We’d often find our tape recorder had gone missing—invariably into his room. He’d play Mohammed Rafi on repeat.” Khan then studied Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (PPE) at Oxford, an unoriginal but often influential choice for aspiring politicians. But it was cricket—and a well-publicised social life beyond music—which consumed not only Khan but the diary sections of every British tabloid newspaper.

In 1983, a few weeks before I arrived in Pakistan for the first time, he achieved the rare feat of scoring a century (117) in the Faisalabad Test match against India and taking 11 wickets in the same match, a record only Ian Botham has achieved in Test history. I am reliably informed that this was the equivalent of Shohei Ohtani throwing a complete-game 2-hit shut-out with 12 strike-outs and hitting two home runs in the same game.

I was at Dean’s Hotel in Peshawar, in the North-West Frontier Province, when, on 2 April 1983, Khan received the President’s Pride of Performance award for cricketing achievements. That same year, Wisden named him one of its five Cricketers of the Year—it never crossed my mind he would one day enter politics.

Yet this was exactly what he did. In 1996, he founded Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), a “movement for justice,” as he grandly put it, although the early years must have been humiliating for a man used to getting his way, because in the 1997 election the party failed to win a single seat. In 2009, when I was also in Pakistan, Imran Khan was politically active but still operating on the margins of Pakistani national politics. However, he still built up enough support to enter the National Assembly in 2002. Over the next decade, PTI grew into the largest party, culminating dramatically in his election as Pakistan’s 22nd prime minister.

Unfortunately for Khan, his premiership from 2018 to 2022 hit a barrage of economic challenges, including skyrocketing prices, nosediving reserves, and a sense of national restlessness, later exacerbated by the ubiquitous Covid-19 pandemic. He responded to this with rather grandly advertised welfare initiatives, praised by sycophants and devotees alike as proof of a kind of moral purpose, though inevitably mocked by many of his opponents as the gestures of a man way out of his depth—an accusation often, probably unfairly, levelled at him.

For some, Khan is a potentially anti-imperialist, anti-elite-populist who could bat away any entrenched power even with imperfectly struck shots. For others, he represents a neoliberal, populist leadership that uses leftist words without delivering any kind of social justice or change. Many are ambivalent about him even when recognising his mass appeal.

To be fair, his legacy includes the Ehsaas Programme for the poor and the Sehat Sahulat health-insurance scheme for vulnerable families. There was also all that emergency cash support during Covid, which millions relied on—not bad for a population of now over 241 million people. His government also offered subsidies on basic foods and made cuts to what were called the trappings of office, gestures basically meant to signal solidarity with ordinary Pakistanis. Regardless of anyone’s political stance, such initiatives represented a humane and socially conscious period for his premiership.

Then, on 10 April 2022, a cricket-like bouncer from hell was aimed at him with a stinging no-confidence vote that made him the first Pakistani prime minister to be formally unseated. It was as if history itself had been menacingly waiting to turn against him.

Though it was said the opposition engineered the vote, Khan blamed foreign interference, initially pointing to the United States. “America threatened me,” he claimed, in a televised address, though later he revised this to “a foreign country,” without convincing anyone the reference had changed. He produced a supposed diplomatic “cipher” from a US official, Donald Lu, warning of consequences if he remained in power. To Khan’s supporters, of course, it was proof of a regime-change plot.

But the alleged cable has never been released in full. Its authenticity remains disputed. And US officials flatly denied involvement, even if critics said they would do that. Pakistan’s own National Security Council found no conclusive evidence of so-called foreign interference, analysts arguing that domestic politics—coalition betrayals, economic torment, salty relations with the military—were enough in themselves to bring down Khan, as if there was no need for foreign interference. Rumours also circulated of opaque dealings with China, though nothing was ever verified.

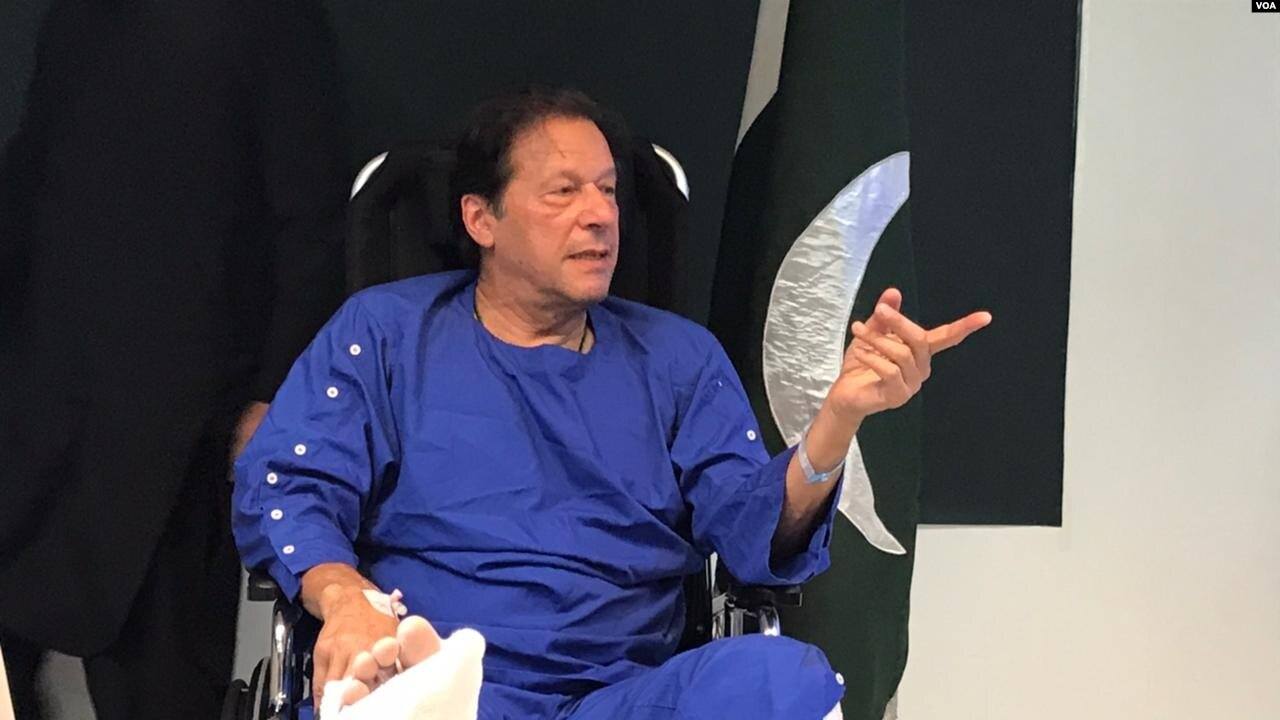

On 3 November 2022, during a protest march in Wazirabad, Khan survived an assassination attempt when he was hit in the leg in an attack that used both a pistol and an AK-47. Supporters were injured and some killed. The person convicted was Muhammad Naveed. Khan maintained it was part of yet another larger conspiracy involving senior political and military figures, a claim that remains controversial and unproven in court, but left to linger like a bad smell. Whatever the story, the attack shocked Pakistan and heightened already explosive political tensions.

After his August 2023 arrest, Khan faced a plethora of cases, now reportedly numbering over 180. In January 2025, he received a 14-year sentence in the Al-Qadir Trust case. While we have to assume he is alive, it has already been a dramatic descent from national hero to long-term inmate. His sister says he is physically healthy but suffering from severe psychological strain. He is said to be held in harsh conditions, subject to isolation, restricted movement, and almost no access to lawyers or relatives. George Galloway has gone so far as to say Khan is being held “in a death cell.” Social media swirls with wild claims that he is being fed slow-acting poison. Further unverified posts allege dementia and liver damage, but these are denied. However, his health raises the question of whether he will ever return to political life.

For now, though, there continue these unpleasant rumours, fears, and the persistently unsettling sense that this story may reach its final chapter before the world even hears it—Lahore firecrackers or not.

The post Khan in the Dark appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed