During the power outage following the winter storms of 2021—known in Texas as Winter Storm Uri—Rita, an Indigenous woman who lives with severe mental illness and congestive heart failure, tried with her then-partner to stay warm in brutal conditions in a tent on the streets of Austin with camp stoves and a propane heater. They survived, but at least six unhoused people did not.

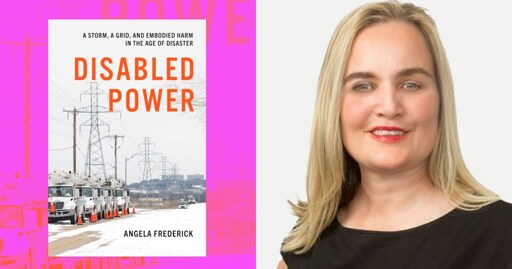

In her new book Disabled Power, University of Texas at El Paso professor Angela Frederick details the challenges that disabled people faced when parts of the state’s power grid failed in February 2021. Frederick’s book outlines the unique challenges that disabled and chronically ill people face when they lose power, including the lack of resources among local governments to assist them during climate disasters.

“Their worlds shrunk in ways specific to disability, and they often negotiateddisability-related constraints as they strategized to survive,” Frederick wrote.

I spoke to Frederick about how policy decisions led to horrors during Winter Storm Uri, what it means to be an energy-dependent individual, and how there needs to be better planning to help disabled people survive climate disasters.

You write that Texas “is known for its exaggerated ideology of rugged individualism and its allergy to federal government intervention.” How did that lead to policy decisions that contributed to parts of the power grid failing during Uri?

I began this project thinking I was going to tell a story that was uniquely Texan. After all, we are the only state in the country to have our own, isolated power grid. By the end of this project, however, I came to view Texas as a canary in the coal mine. You can practically draw a line from the period in the 1990s and early 2000s when the state deregulated the grid to the tragedy that occurred during Winter Storm Uri in 2021. This was a project spearheaded by the now-defunct corporation Enron. Enron’s executives wanted to make money off the sale and trade of electricity. And electricity came to be seen as a commodity far more than a public good. This, as I came to understand, is not at all a story unique to Texas.

What are energy-dependent individuals? How are they more vulnerable during climate disasters?

Most people with disabilities and chronic health conditions could be categorized as power vulnerable. These groups can experience heightened pain, illness, or limited mobility during long-term power outages due to spoiled medication or loss of assistive technology. But there’s another group in the disability community we call power dependent. These community members need power for their very survival. These community members rely on electric-powered durable medical equipment. And these individuals’ lives are in immediate danger when power goes out.

What struck me is that some people you spoke with did register with utility companies, outlining that they needed power to survive, but they were not helped. Do you think that speaks to the fact that potential solutions could still fail us?

I think it certainly speaks to the limitation of the individual preparedness model for disaster resilience. There’s so much emphasis on this long list of things we need to do to be prepared for an emergency. And these are really important things to think about.

Some people I interviewed blew off the warnings about the winter weather, and they could have fared better if they had been more prepared with food and supplies. But, also, some people I interviewed did everything imaginable to be prepared for a long-duration power outage, and they still found themselves in life-threatening conditions. They were told, to be prepared for an emergency, register as a power-dependent customer, and register for STEAR, the State of Texas Emergency Assistance Registry. And they dutifully registered, got a doctor’s certification, and reregistered every year. And it turns out registering as a power-dependent customer does not keep the lights and heat on in the case of rolling power outages. There isn’t an individual switch [for] each household. And as it turns out, registering for STEAR did not provide any additional layers of safety for people.

People really felt betrayed by this. They were asked to register for these things, yet it meant nothing in their greatest time of need. Ultimately, being prepared at the individual level is good and important, but the most important thing we can do to keep people out of danger is to strengthen public policies so we don’t find ourselves enduring these preventable infrastructural failures.

Could you talk about what care webs are, and how they can be lifesaving when infrastructure fails disabled people?

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha defines care webs as informal networks of disabled people and nondisabled people who provide care for one another. In contrast to charity models, which are characterized by power imbalances, care webs involve reciprocal relationships in which interdependence is highly valued. Many disabled people are networked with one another already through formal organizations, informal community networks, and on social media. What I found in my research is that people in these networks became spontaneous care webs for communities during Winter Storm Uri. The Deaf community, for example, were very organized in checking on one another and even distributing water immediately following the crisis. Blind people also showed up for one another in really remarkable ways.

Climate events are going to continue getting worse and more frequent, and it seems like it could be a matter of time before history repeats itself with another Uri. What are a few changes that you think could reasonably mitigate harm during another energy crisis?

Well, of course, I think our collective responsibility is to prevent these failures in critical infrastructure. We must regard infrastructure like power and water as a public good that must be fiercely protected. This is a win for everyone, including people with disabilities.

In addition, my book is really a call to put disabled people at the center of climate and disaster responses. With almost every disaster, we can find stories of disabled people who perished or experienced harm because emergency response systems were designed around the assumption that everyone in the community can see, hear, stand in long lines, drive, etc. And people ultimately get excluded from community response systems when we leave disability as an afterthought.

Approaching this from a different angle, I think there is great power for entire communities when we place disability at the center of resilience planning. Centering the perspectives of people with disabilities, we can more easily spot the vulnerability points in our planning. And when we correct for these vulnerability spots, many more people will benefit.

From Mother Jones via this RSS feed