In 2023, I entered the US Forest Service with my cohort of 130 recent college graduates, many from underrepresented populations.

Growing up in California, I saw both beautiful natural areas and the devastating impacts of drought, extreme heat, and wildfire. I’ve always seen climate change as a terrifying but compelling subject, and I chose a career that allowed me to directly face it. I was excited to be surrounded by like-minded people whose passion led them to public service, where we felt like we could make the greatest impact on the future state of the natural environment.

Two years later, I was effectively forced out of my position alongside nearly 5,000 Forest Service employees (and 317,000 federal employees overall).

But these numbers don’t tell the full story of the losses that will take unimaginable efforts to rectify. Taxpayer-funded resources were stolen from the public. Institutional knowledge built up over decades was erased overnight. And young people recruited into supposedly secure careers were thrust into a pool of uncertainty.

We lost taxpayer-funded tools and resources

The US Forest Service’s motto is “Caring for the Land and Serving People,” with work ranging from sustainably managing National Forests and mitigating wildfires, to assisting cities and communities with tree care, to conducting forest conservation research. I worked for a branch of the Forest Service called State, Private, and Tribal Forestry (SPTF). Although a small portion of the federal government as a whole, SPTF plays a critical role, one that I believe the federal government fundamentally ought to play: providing resources and support to communities who need it most.

My team was filled with incredibly dedicated and passionate public servants who were taking care to distribute and manage resources in a way that would truly be beneficial to communities, especially to those that the government has historically not invested in.

My colleagues who had worked for the Forest Service for decades told me about surviving the many administration changes they had experienced in their careers—including the first Trump administration. But this time around, things were clearly different.

Before the inauguration, Monday mornings were very normal: I would plan my work for the week, answer questions from my grantees, and chat with my coworkers about our weekends.

After the inauguration, each Monday was steeped in stress that our whole program may disappear or that we would receive another Friday evening email vaguely stating that our positions were being evaluated. It became a daily challenge to figure out how to reassure our grantees amidst so much uncertainty. When they asked us if they would lose their funding, the best we could tell them would be: “In a normal administration, you would not have to worry about signed and executed grants being rescinded.”

But in 2025, the newly created Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) cut slews of signed, in-progress grants. Per an Executive Order banning DEI, DOGE flagged projects based on terms like “equity” in the titles, and grant terminations came with little warning. With these cuts, valuable forest conservation work was halted, including critical wildfire management work, at a time when forest fires are getting worse.

In addition to taxpayer-funded grants, we also lost taxpayer-funded tools that determined where those financial resources were most needed.

My teammates and I were devastated to see the removal of online, publicly available tools that are used nationwide to allocate grants to communities that face disproportionate environmental burdens (such as air pollution and extreme heat) and socioeconomic burdens (such as low-income households). Many of these tools were supported through multiple administration changes: they were not considered partisan, but rather essential mechanisms to carry out necessary work.

These tools included the Center of Disease Control (CDC)’s Social Vulnerability Index (developed in 2007), the Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice Screening Tool (developed in 2012), and the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (developed in 2021).

Although a court order required the Social Vulnerability Index to be restored after its removal, the yellow box now appears on the Center for Disease Control’s website. Source: CDC

Beyond allocation of resources, these tools were also used for research critical to human health. For example, all mentions of the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index were suddenly removed from federal websites on January 31st to comply with Executive Order 14168 targeting transgender health equity. The Social Vulnerability Index has been cited in over 5,400 articles to examine health outcomes—including cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and opioid overdoses—and the tool’s removal caused so much pushback that a court ordered it to be restored.

These removals also broke the US government’s longstanding practice of data justice: sharing the data that it collects back with the people who it represents, and whose tax dollars pay for it. By the hard work of outside entities, many of the other tools have been restored to external sites. This allows them to be viewed as they were before. But as unofficial tools, they can no longer be used by federal agencies to allocate resources to communities who need them the most.

We lost institutional knowledge

In 2023, 42.5% of the federal workforce was over 50 years old (compared to 33% of the U.S. labor force), while only 7.4% was under 30 (compared to the U.S. labor force’s 20%).

Entering the Forest Service at 25, I was the youngest in my office and among the youngest in my program. It was my first full-time job out of graduate school, and I leaned on many wonderful mentors to teach me how to navigate federal work.

The majority of my mentors were approaching retirement age, and it was both implicitly and explicitly said that they were training my group of young, newly hired colleagues to take the reins in the not-too-distant future. They were relieved to not only be growing their team, but also to be passing on institutional knowledge.

In my program, the most impactful form of institutional knowledge was the trust that had been built with our external partners. As an agency that works directly with states, tribes, and communities to distribute and manage financial assistance, it is vital to the success of the work and to the equitable distribution of the federal dollars that the Forest Service is seen as a trusted partner. Beyond rescinded grants, the interpersonal relationships that are built over decades are of immense value. I know that these relationships have been severely fractured by sudden departures of both the longstanding program leaders and of the younger people they were introducing to partners to carry on that legacy of trust.

While the federal workforce cuts directly impacted newer employees the most, my mentors were left with a drastically diminished team—from twelve people to just three on my core team. Some vital programs were disbanded entirely. Many positions of people who left were not backfilled, so my remaining colleagues ended up absorbing portfolios of new work they were unfamiliar with.

I’m worried that with the exodus of young federal employees and the slew of early retirements that many of my colleagues felt forced to take, the institutional knowledge of the older generation will be lost, which will have an unknowable impact on the future federal workforce.

We lost a generation of passionate young people

As a student passionate about climate change and social justice, I knew I might have to accept lower pay as a trade-off for work that I felt was impactful. But the trust that public service would provide job security—touted by family members, federal employees, and my graduate school career advisors—reassured me that I wouldn’t have to compromise my values for the career I was passionate about. I applied for my federal job with the knowledge that the most uncertainty lay in overcoming the barriers to entry, which these pathways programs are designed to mitigate.

The internship that began my federal career is one of many Forest Service programs designed to recruit youth, students, and recent graduates into federal careers. With higher salaries in the private sector drawing more young people away from the federal workforce, pathways programs like these are critical to steadily lowering the average age of federal employees.

For example, according to the Office of Personnel Management, the average time it takes to hire a federal employee has been increasing, and was at 101 days (over 3 months) in 2023, compared to the 30-45 days of private sector averages. I was confident that once I was officially hired as a Forest Service employee, I would not have to worry as much about losing my job as I would at a private or non-governmental organization.

The federal pathways programs were slowly chipping away at the barriers for young people to become public servants, offering incentives like direct hire authorities after the completion of 6-12-month internships. By forcing us out of our positions—either permanent or mid-pathway—2025 broke the trust between young people and federal careers, and that trust won’t be easy to gain back.

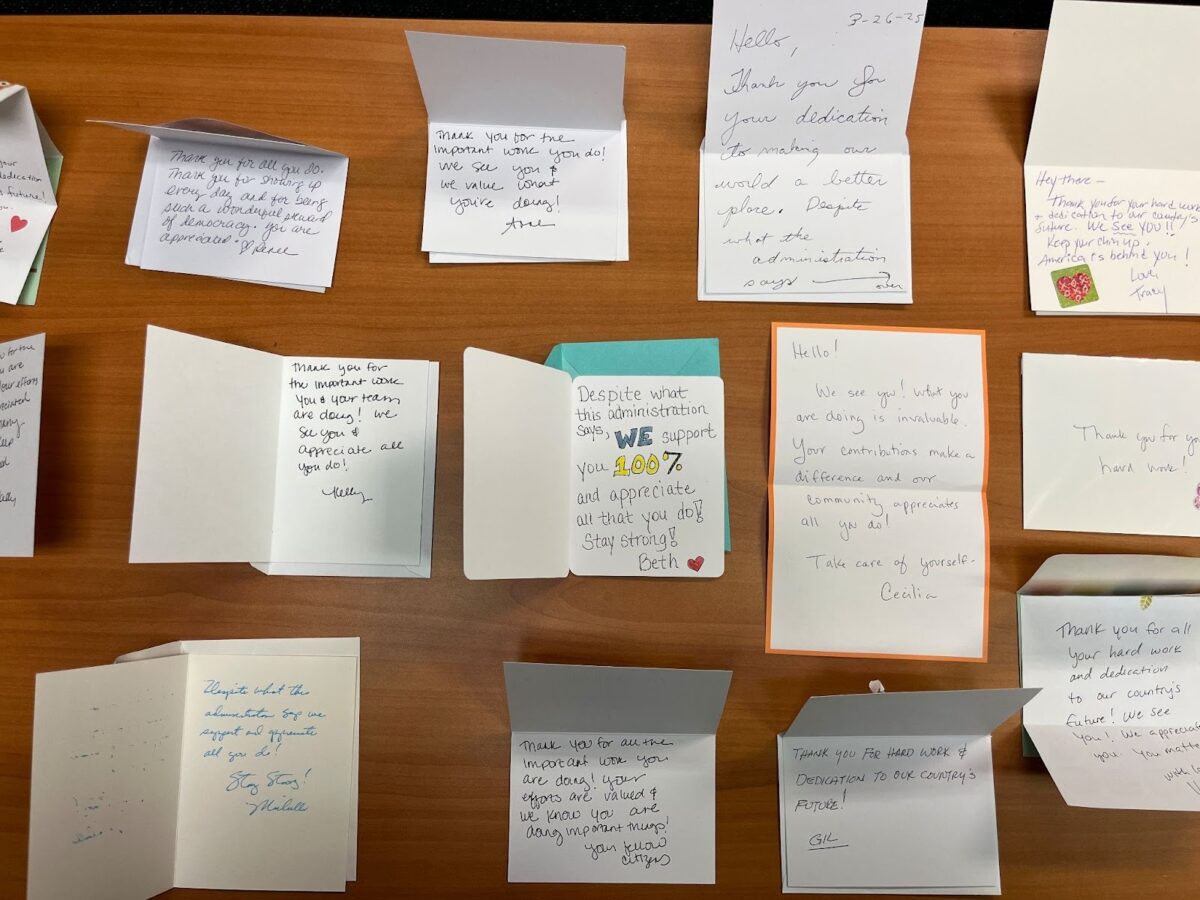

A group who didn’t know my officemates and I personally but knew we were a federal office sent us this collection of letters.

I was fortunate to have found another job in my field five months later, but many of my ex-colleagues are still searching. When family and friends ask if I would ever return to public service, I don’t really know what to say. There is so much uncertainty about what the future federal workforce will look like, and these issues won’t be solved in four years.

But I am given hope by the external organizations who quickly rebuilt the federal tools. By the group of strangers who sent handwritten letters to my office in March because they knew federal employees were going through a hard time. By the Hands Off and No Kings protests across the country in April, June, and October. And by my former colleagues who worked during October’s 43-day government shutdown, despite not getting paid, because they knew this work is necessary and cannot be paused.

It will take the continued advocacy of all these people, and the understanding of our work’s value by people with decision-making power, to rebuild what we have lost.

From The Equation via this RSS feed