As dust settles from a historic deal that saw Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko free 123 political prisoners in exchange for a partial U.S. sanctions relief, the main question remains unanswered — what now?

Trump’s newly appointed special envoy, John Coale, arrived in Minsk on Dec. 12 and secured the biggest prisoner release so far, with Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ales Bialiatski and leading opposition figures Viktar Babaryka and Maria Kalesnikava walking free the following day.

The inclusion of Babaryka, Kalesnikava, Bialiatski, along with the editor-in-chief of the country’s biggest independent outlet tut.by, Maryna Zolatava, veteran politician Pavel Seviarynets, and prominent political analyst Alexander Feduta, marks the most high-profile release yet.

Subscribe to the NewsletterBelarus Weekly

Join us

In return, the Treasury delisted Belaruskali and its subsidiaries, allowing Belarus to trade potash with the U.S. and longtime customers in China, India, and Brazil.

Now, Belarus observers are closely watching seemingly unconnected developments — whether Belarusian opposition figures, kept behind bars for years, will add a spark to the largely curtailed movement, and whether the relief of sanctions will help bolster the Belarusian economy, somewhat decoupling it from that of Russia.

The answers to those two questions will likely shape the country’s future.

Putin’s loudspeaker

Reengagement between Washington and Minsk appears to be accelerating, with more high-profile political prisoners being released and tougher sanctions being lifted. It coincides with another diplomatic push to get Ukraine to agree to a contentious peace plan involving territorial concessions to Russia.

"This is all part of their engagement agenda with Putin’s regime, with very questionable strategic gains or goals,” says Dr. Giselle Bosse, chair in EU Foreign Policy and International Relations at Maastricht University.

She says that the U.S. officials appear to believe Lukashenko can potentially act as a mediator between the West and Russian President Vladimir Putin, but that Belarus’ military, political, and economic integration with Russia leaves him little real autonomy.

"He’s a proxy of Putin, more of a loudspeaker of Putin’s regime than the other way around,” Dr. Bosse told the Kyiv Independent.

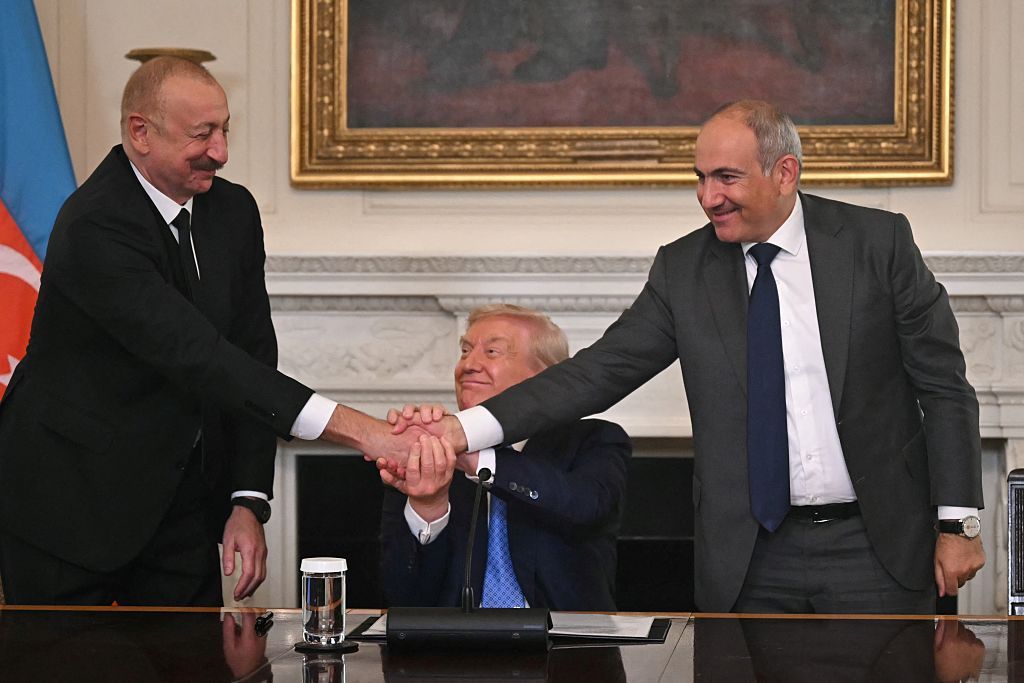

Analysts see reengagement as part of Donald Trump’s attempts to “get into Russia’s backyard” — to pull various post-Soviet countries out of Russia’s geopolitical sphere. The idea was the driving force for Trump hosting the leaders of Central Asian countries at the White House for the first time in history. He also hosted the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan in August, signing what Trump called a peace agreement between the two sides.

U.S. President Donald Trump ©, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev (L) and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan shake hands after signing an agreement in the State Dining Room of the White House in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 8, 2025. (Andrew Caballero-Reynolds / AFP via Getty Images)

"The U.S. views Belarus as Russia’s domain. And they view contacts and cooperation with Lukashenko as part of their future policy toward Russia,” says Alexander Friedman, lecturer of Eastern European history at Düsseldorf University in Germany.

Analysts say, however, the impact of U.S. sanctions relief may be limited while European restrictions remain in place, keeping Belarus cut off from key export routes.

"There is an ever-widening divergence in the positions of the United States and the European Union regarding Belarus. (…) This clear contrast will severely limit all sanctions-lifting measures the United States is taking,” political analyst with Radio Free Europe, Valery Karbalevich, told the Kyiv Independent.

Geopolitical considerations aside, all experts who spoke with the Kyiv Independent agree that Trump’s ambition to secure a Nobel Peace Prize significantly contributes to sustaining diplomatic engagement with Minsk.

Read also: ‘Article 5’ without NATO — Why security guarantees may fail to protect Ukraine

Prisoner diplomacy

Since the nationwide anti-government protests in 2020, over 3,000 political prisoners have served their full terms, and hundreds of political prisoners were released in several rounds of pardons.

Yet for the prisoners released with the U.S.-mediation, freedom comes with forced expulsion from their country, which may amount to forced deportation under international law, Human rights advocates say. Lithuania referred the issue to the International Criminal Court, though no other country has joined the case so far.

The number of the released can’t be taken at face value either, argues Vytis Jurkonis, head of Freedom House Lithuania.

Belarusian opposition figure Maria Kalesnikava after being released from prison in Belarus on Dec. 13, 2025. (Ukraine’s military intelligence service)

"Whether (the regime) is just trying to mess up with numbers, or it is an attempt to dilute the definition of the political prisoner, every single case needs to be thoroughly analyzed,” Jurkonis told the Kyiv Independent.

Among the Lithuanians released in September, only one person qualified as a political prisoner, whereas in November’s release of 31 Ukrainian citizens, human rights activists established the politically motivated nature of prosecution in roughly a third of the cases.

"We also see the new detainments and arrests, so the numbers of repressions continue, and the number of political prisoners is likely to grow. So there is no systemic change,” Jurkonis says.

Upon returning from Minsk, Coale announced that the release of a group of 1,000 prisoners is achievable in the coming months. As most American sanctions were introduced over human rights abuses in Belarus, they can be lifted as the prisoners are being released.

"I think it’s a fair trade,” Coale told the DWS News in Vilnius on Dec. 13.

Marred release

The crowd gathered near the U.S. Embassy in Vilnius within hours on Dec. 13, eager to greet their heroes. Lithuanian authorities were prepared to issue visas, and local human rights groups have booked accommodation for over 100 people.

Much to everybody’s surprise, 114 of 123 prisoners were diverted to Ukraine. Vilnius has received the Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Bialiatski, founder of Viasna human rights center, and eight foreign citizens from Lithuania, Latvia, Japan, and Australia.

“Belarus did not want to release political prisoners to any EU country, and because of that, they were sent to Ukraine,” President Volodymyr Zelensky said, adding that Minsk contacted Kyiv via intelligence channels to ensure that Ukraine was ready to receive the prisoners.

Belarusian Nobel Prize winner Ales Bialiatski speaks to journalists at the U.S. embassy after he was released in Vilnius, Lithuania on Dec. 13, 2025. (Petras Malukas / AFP via Getty Images)

"Prisoners were taken somewhere where no journalist or opposition members were waiting for them. Belarusian authorities didn’t want to give additional points or extra attention to the opposition,” Karbalevich thinks.

Friedman views Lukashenko’s move to redirect prisoners to Ukraine as an "attempt to get involved in the negotiation process on Ukraine,” as Belarus has previously facilitated Russia-Ukraine POW exchanges and released 31 Ukrainian citizens in November, reportedly, at the request of the American administration.

The arrival of Belarusian prisoners is interpreted by analysts in Ukraine as “imposed,” a gesture that Ukraine could not refuse the U.S.

"This is a one-off action that has nothing to do with improving the current state of Ukrainian-Belarusian relations or with revitalizing relations with Belarusian democratic forces,” said Ihor Kyzym, former Ukrainian Ambassador to Belarus.

New center of Belarusian opposition?

Belarusians, both those exiled and those within the country, rejoiced over the release, raising $100,000 to support the former prisoners within two hours.

About as important as the lists of releases are the names of those who were not freed. Most notably, Poland did not receive a Polish-Belarusian activist, Andrzej Poczobut, despite the reopening of the border checkpoints.

For each group of the released, a person is missing: Babaryka is released, yet his son, Eduard, remains in custody. Editor-in-chief of the country’s major independent news outlet, Zolatava, is now free, but the CEO of the outlet, Liudmila Checkina, remains in jail. Viasna has received back Bialiatski, but one of his colleagues, Valiantsin Stefanovich, remains imprisoned.

Holding relatives or team members hostage serves to make sure that the released prisoners keep a low profile abroad, analysts believe. In a snap press conference in Chernihiv, former prisoners refused to speak on certain topics, including Russia’s war against Ukraine and the horrors faced behind bars, citing fear of harming those still imprisoned.

The release of Babaryka, one of the favorites to win the 2020 election, can potentially split the opposition movement, facing multiple strains.

He might join and strengthen existing structures, or add to internal conflicts within the opposition, those who spoke with the Kyiv Independent believe.

No winning strategy

Proponents of continued engagement with Lukashenko argue that years of sanctions have not helped release political prisoners from Belarus. However, the previous rapprochement with Lukashenko in 2014-2015 did not bring about fundamental changes in Belarus or win Lukashenko over from Moscow.

"We’re not choosing between winning strategies, I’m afraid,” Besse says.

"European sanctions must be left for bigger issues, for irreversible and systemic changes,” Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya told the press at the U.S. embassy on Dec. 13.

The systemic changes indicating liberalization must include the release of all prisoners, the possibility for the return of those forcibly expelled, and the restoration of consular services for Belarusians abroad, human rights groups say. Extremist labels must be removed, and independent Belarusian media must become freely available in Belarus.

The liberal shift would help restore the anti-Kremlin and anti-Moscow guards in Belarus, according to Jurkonis.

"It’s the people, the civil society, human rights defenders, and independent media, which are the main guarantee of the sovereignty and independence of Belarus, certainly not one guy who is basically a vulnerability,” Jurkonis says.

For now, analysts say, the releases ease pressure on Lukashenko without signaling broader political change, leaving hundreds still imprisoned and Belarus firmly tied to Moscow.

Read also: How fragmented sanctions prolong the war and empower Russia’s defense industry

From The Kyiv Independent - News from Ukraine, Eastern Europe via this RSS feed