Today’s post is inspired by a contentious podcast debate I recently had—video linked below. It got me interested in creating several posts as resources to debunk three key myths that underlie “common sense” thinking about the punishment bureaucracy. These myths present themselves in some form in nearly every conversation I have with fancy people about crime and safety in our society, and it’s useful for us to have simple responses to them for whenever we encounter someone among our friends and family suffering from a case of Copaganda brainworms.

And so, in the next two posts, I will address three mythologies at the heart of public discourse on the punishment bureaucracy. These are things that almost every mainstream pundit gets wrong (intentionally in many cases and through ignorance in others). These are three things numerous politicians, political consultants, and random fancy people regurgitate to me in private in some form or another:

Preserving (and even expanding) existing police, prosecutors, and prison bureaucracies is a good/effective way to promote safety. The benefits to safety of more punishment, surveillance, and centralized government control are seen as so obvious that they are taken for granted as the opening premise. In the imagined “common sense” world of elite opinion avatars, this often goes something like: If you care about people being safe, of course you must oppose reducing the size and power of the punishment bureaucracy.1

The bureaucracies of government repression—and the multi-billion dollar corporate industries parasitic on them—have no negative relationship to democracy, no profound effects on civic participation, no crushing effects on progressive social movements, and minimal externalities overall. Again, “common sense” punditry pushes something like the following view: There are no significant tradeoffs to discuss or consequences to think about when a society expands its capacity to surveil, repress, and operationalize state violence. Nothing to see here!

Reducing the size and power of the police, prosecution, and prison bureaucracies is unpopular. If you watch the video below, you’ll see my interlocutor shouting this at me. And if you walk into the bathroom at Democratic National Committee, you’ll overhear the following conversation between toilet stalls: “We would LOVE to reduce state repression but it’s just not what people want… Yeah, our genuine desire to do what the people want is the only thing stopping us from pursuing more effective, egalitarian, and liberatory public safety policy.”

In today’s post, I’ll debunk myth number 3, hopefully forever. Next time I’ll tackle 1 and 2.

A request for help

But, before I go there, I need to do a short plug. We had a rough year at Civil Rights Corps, with some philanthropic foundations abandoning us amidst a climate of retrenchment away from fighting mass incarceration. But it is precisely in this moment that the civil rights work we do to combat human caging, family separation, pretrial detention without due process, and authoritarian repression is more important than ever. Please consider making a donation here as we enter 2026, which is our 10th anniversary year! As a special incentive, I can offer a signed copy of Copaganda to anyone who donates more than $250 or who commits to a monthly contribution of $25! If you would like that, please make your donation at the link above and send an email with your address to quinita@civilrightscorps.org. We do the highest impact litigation at extraordinary levels of excellence.

Moreover, you can now, for the first time, order Civil Rights Corps merchandise that also supports our work. This even includes some limited-edition Copaganda gear that I’m told is popular in Paris, Milan, and in the zip code that includes my grandmother’s house in Pittsburgh:

The strange debate

I recently agreed to debate a prominent advocate and pundit named Matt Stoller because there are almost no instances in mass media where there is a conversation about the role of police, prosecutors, and prisons that gives time to a person critical of those institutions. The result of this curated silence is that many avid consumers of news—including professionals in media, politicians, and huge numbers of ordinary people—are uninformed/misinformed about the punishment bureaucracy. (I have a section of the Copaganda book that I am particularly proud of where I show with hilarious examples from the New York Times how this ignorance is manufactured by surgically excluding sources, ideas, and evidence critical of the punishment bureaucracy.)

Before I go on, I want to say that I’m not necessarily recommending you take the time to watch or listen to the podcast debate. I link the video here in case you remain interested after reading this post, and because the debate got me thinking about the need for specific posts about “common sense” and “conventional wisdom.” I am grateful, though, to Briahna, for opening up the space for the conversation, and I was sorry that my interlocutor yelled at her. She is an excellent interviewer and moderator.

Like so many people with prominent platforms and ostensibly left-leaning politics, the person who debated me has said uninformed and misleading things about the punishment bureaucracy repeatedly and with great confidence to hundreds of thousands of followers. But, he admits in this debate that he has no idea whether these things he has been assuming, implying, and stating are true or not. This is typical in my experience with elite punditry. Instead, as the conversation goes on, he keeps repeating the same fraudulent talking points associated with people like Tom Cotton, Kamala Harris, whatever contract the Atlantic must make people sign before they sell their souls, the Washington Post Editorial Board, and Donald Trump. As I explain with a lot of evidence in Copaganda, the standard establishment talking points on crime and safety are the contemporary equivalent of tobacco company misinformation or climate science denial. It’s important to understand why so many Smart People are paid to regurgitate them. And the reason I tried to have the conversation is that, once you peel away the layers of fraudulent assumptions and fill in the available empirical evidence, the specific policy agenda of progressive critics of the punishment bureaucracy is one of the most obvious and popular policy agendas in contemporary society. So, we must give people tools for critical thinking in the face of such relentless propaganda.2

As so often happens when someone is forced to admit the empirical facts supporting their pro-punishment positions are wrong—or that they don’t know the empirical facts—my interlocutor turns to the common refrain: okay fine maybe you’re right but your views aren’t popular with the people! This flat-earther view, represented most forcefully in contemporary punditry by another Matt, Matthew Yglesias (winner of a prestigious Copaganda award in my book and who not coincidentally has an op-ed today in the New York Times arguing that “Liberals should support America’s oil and gas industry”), is simplistic and wrong. It must be eradicated from good faith conversation.3

The assertion that more progressive views on the government/corporate punishment industrial complex are not popular is quite funny on at least two levels: 1) the people saying this to me typically don’t understand those progressive policy views because they have not bothered to read about them or to study what they are based on. As I’ve written before, one of the defining features of contemporary punditry is that people on the left are constantly engaging with liberal ideas and output but establishment liberal pundits rarely read the scholarship and analysis of the left or seem to be part of spaces in which they learn about those ideas in any depth; 2) The available evidence suggests that reducing the size of the punishment bureaucracy in favor of more liberatory, egalitarian, and effective safety policy is extremely popular!

Popularity

Mainstream discourse is so hollow and superficial that it is almost impossible to locate a single instance of establishment media having a good faith conversation about what kinds of punishment policy is “popular.” I am on a mission to end that because I believe that, if we have any hope of creating a successful anti-fascist coalition, we must improve the understanding of people within that coalition of how our contemporary system of government-corporate repression works and how that system affects the possibility of flourishing participatory life in a civil society.

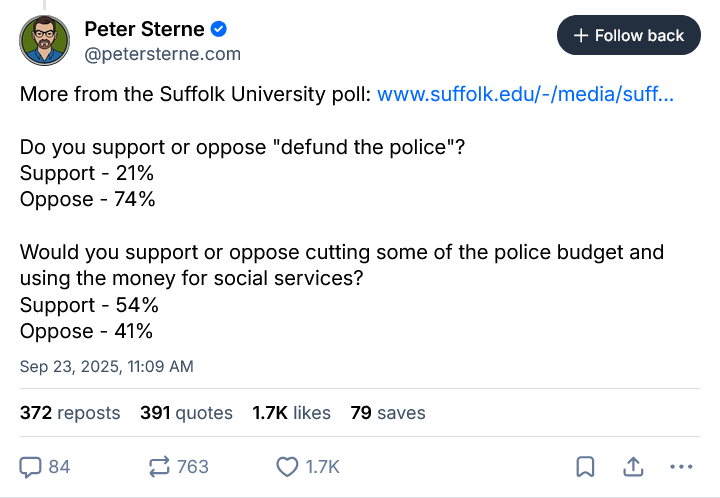

I urge you to read Chapter 12 of Copaganda about polling. In it, I give the representative but fascinating example of a newspaper article about a poll in which “Defund the Police” is portrayed as unpopular in the Los Angeles Times. However, the paper simply ignored the more detailed parts of the poll in which people were asked about the underlying policies of “defund” campaigns. When asked about actual policy, overwhelming supermajorities of the population (Democratic, Independent, and Republican) all supported taking money from the police budget and giving it to various social services (70% support overall!). This is striking because, as I note in the book, this is also the social-scientific consensus when polls have been taken of even pro-police scholars. The consensus view is that the empirical evidence shows that investments in things like housing, healthcare, education, and community connection are far more effective in producing safety. Thus, we have a policy issue in which the overwhelming popular opinion and scientific evidence are in accord. Seen this way, it’s an incredible achievement of propaganda that “conventional wisdom” in elite punditry is exactly the opposite.

Since I published the book, polls have continued to reaffirm these truths around the United States, even after unprecedented levels of fear-mongering propaganda in the 2024 election cycle about crime. The same basic dynamic can be seen in a recent Suffolk poll:

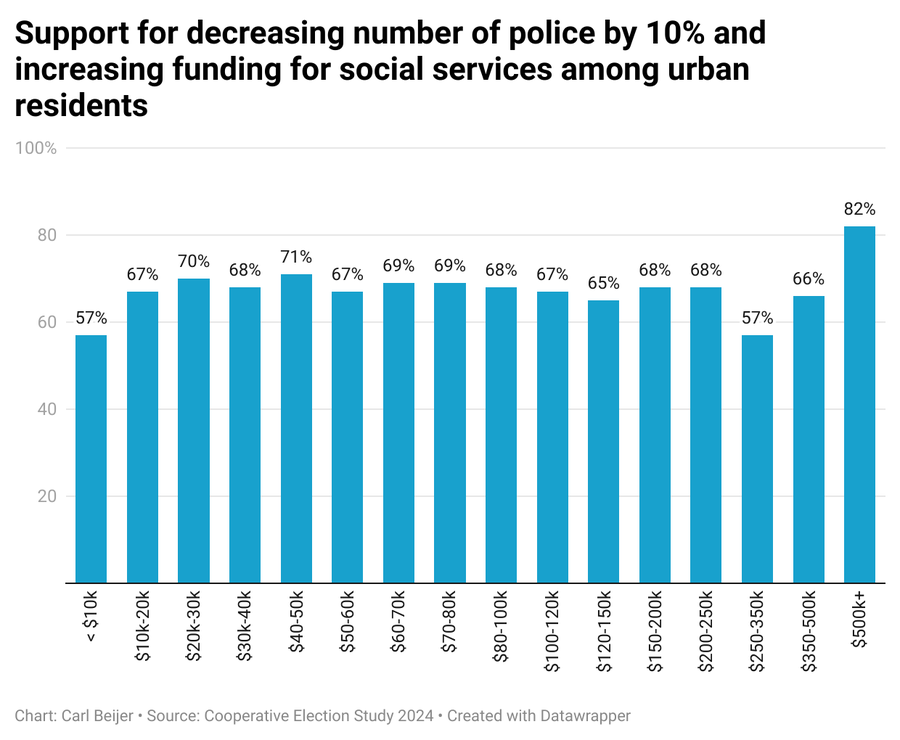

And take a look at this fascinating chart demonstrating how consistent this view is across various class segments of society:

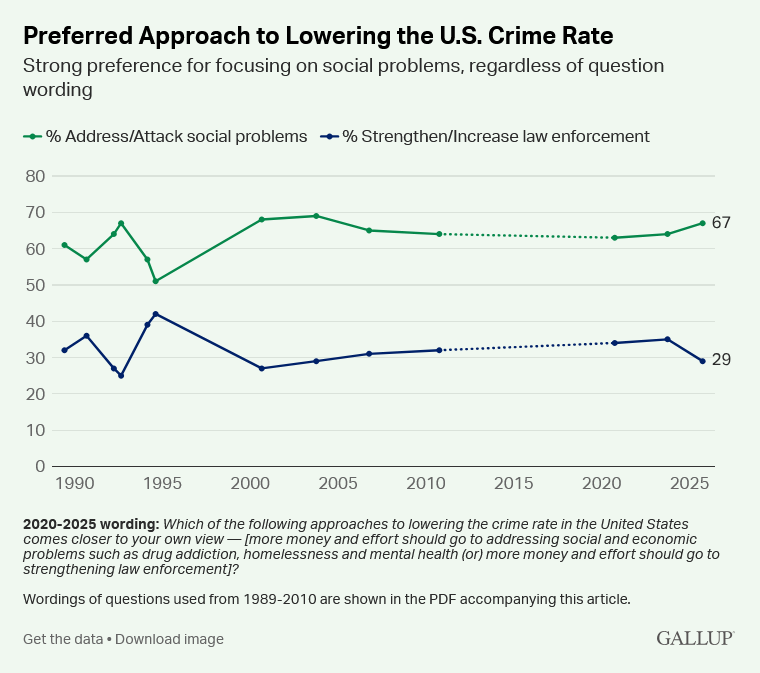

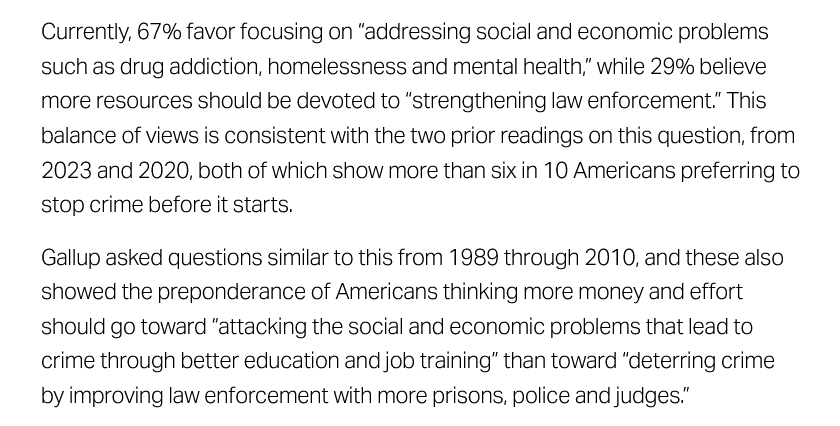

Incredibly, the overwhelming preference of Americans for decades has been shifting resources to social investments instead of police, prosecutors, surveillance tech companies, and prisons. Just take a look at this Gallup chart:

As Gallup itself explained:

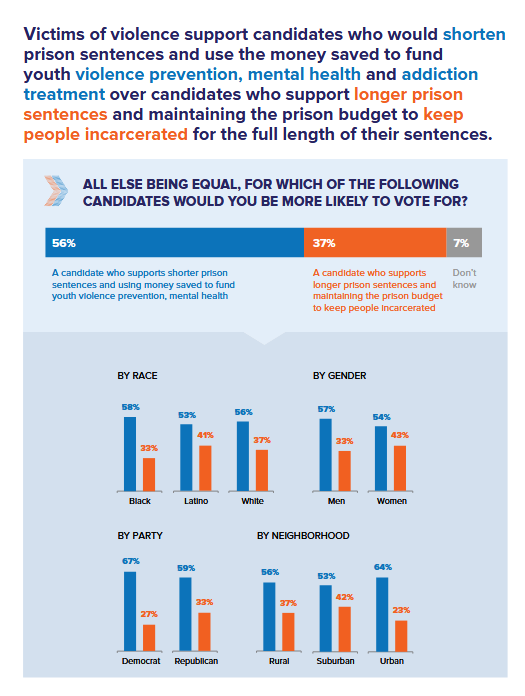

Some time ago, a prominent liberal journalist attacked me in private for “not caring about crime victims, who are disproportionately people of color” because of my public stance seeking to reduce the size and power of the punishment bureaucracy. This is another standard elite pundit move that I address in the book: claiming that the most vulnerable people want more repression and that any attempt to critique the punishment bureaucracy reflects a lack of care about marginalized people. Setting aside how offensive these critiques are to people who have devoted their lives to pursuing holistic public safety for all human beings based on evidence and compassion, it was comical in another way. Crime victims and survivors of violence consistently assert the opposite in polls! And crime survivors, like the rest of the population, express these views across all party lines:

The strategy of the prosecutor lobby, police unions, and liberal pundits to co-opt the compassion of people for crime survivors to scare and mislead the public into supporting policies that don’t work and that go against the consistent wishes of crime survivors is one of the great shames of the last several decades of mass incarceration:

It should be a sobering moment of reflection for everyone involved in mainstream journalism that the conversations they curate about what is popular are so superficial. The best that can be said for mainstream pundits is that they are intentionally having a conversation about a demonized and poorly understood term—“defund”—in order to avoid acknowledging an enduring and longstanding consensus: people want less investment in repression and more investment in systems of care. Basically every single newscast and every single conversation happening in the political consultant and campaign class among Democratic Party figures is proceeding from a set of “conventional wisdom” assumptions that are wrong about what people want and that fly in the face of a scientific consensus.

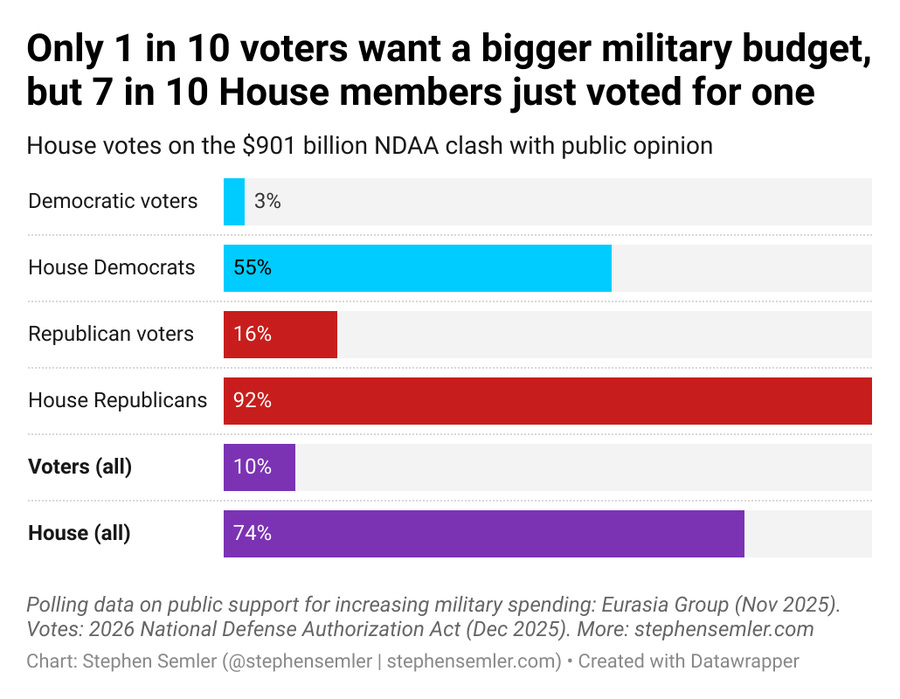

This dynamic is not limited to propaganda in the punishment context. It appears across policy areas. It has been well documented for a long time that even a highly propagandized and jingoistic public does not support the historically unprecedented expansion of U.S. military budgets in recent decades. Polling shows that only 10% of voters supported a larger military budget even as bipartisan majorities keep voting for them.

And, as I noted in Copaganda, a 2012 study by a Harvard Business School economist demonstrated that, even though most people in the U.S. have an inaccurate, highly propagandized understanding of inequality—in which they wrongly believe that the U.S. is much more equal than it is—an astonishing 92 percent of people from across all political parties wanted the U.S. to be more equal than even what they thought it was.

All of this suggests something pundits are paid to forget: there’s a chasm between what actually is popular and both what politicians do and what pundits say. The concept of what is “popular” is either lied about or selectively weaponized to justify policies pursued for other reasons and simply ignored when those who exercise real power in our society have no use for that fig leaf of public consent.

* * *

I want to close with a few points that I elaborate on in the book so that I don’t leave people with the wrong impression. I am not a fan of polling. I don’t think political strategy should be based primarily on polling as it is currently practiced, and I don’t think it is used in an intellectually honest or helpful way in mainstream news or political consulting. First, polling is expensive, and it tends to be done by institutions who have a lot of money and who have particular goals in commissioning polls. It’s more a tool of opinion manipulation than it is of opinion observation.

Second, based on the way questions are phrased, and what informational context is presented to the person beforehand, skilled pollsters can get people to say basically anything, including things that are contradictory. For example, the popularity of police and prisons goes down a lot when you tell people that for decades police chose to arrest more people for marijuana possession than all “violent crime” combined, even as they simply ignored hundreds of thousands of untested rape kits. Or when people are told basic data about police overtime fraud in their city. In more focus group settings, I’ve seen how the popularity of the punishment bureaucracy craters the more people learn basic facts about its ineffectiveness, corruption, and brutality.

Third, polling is an extremely crude way to take a snapshot of how a (heavily propagandized) group of people responds to vaguely worded concepts and phrases without context. This is not nearly as useful as people think it is, because the real questions (even if you’re limiting yourself to such opinion observation endeavors) relate more to understanding underlying conditions such that one can predict how people will feel about things based on different contingencies. For example, if I ask someone on Friday evening if they are happy in their marriage, they may give an affirmative answer, but if I know that on Monday morning they will learn that their spouse is cheating on them, the Friday evening poll is not too helpful. And so we may be more interested in complex questions about what people will think after an effective public education campaign about an issue, after certain likely events occur, or after people are subjected to certain kinds of propaganda.

Fourth, polling does a terrible job misleading people about how social change happens for many reasons, including that it ignores the strength of preferences and does not tell us how to predict changes in common sense that people can organize together to shape through collective action. As I noted in the book, polls do not tell us “how intensely [people] would be motivated to come together with other people to do things in the world to make those things happen or to prevent them from being implemented.” The obsession in the political world with polling leads a lot of people to be worse at predicting what will actually happen and why.

Finally, and most importantly, whether something is presently popular in vaguely worded, context-free, highly manipulated and selectively reported snapshots of manipulated public opinion is a terrible way to decide what policies people who care about liberty and equality should support. For example, as I explained in the book, few liberals pundits I talk to remember that Martin Luther King Jr. was “unpopular” during his lifetime. King had a 75 percent disapproval rating at the time of his assassination, and 60 percent of Americans said that they opposed the March on Washington when it took place in 1963. The same is true of historical fights against the theft of Indigenous people’s land, women campaigning for suffrage, and LGBTQ advocates organizing for same-sex marriage. They were unpopular in polls and attacked by mainstream media pundits for being naive because of their supposed “unpopularity.” But now most Americans hold those fights in high esteem because social movements can both reveal and change mass consciousness. In other words, passionate and committed work in pursuit of truth and justice can change what feels like common sense.

But contemporary pundits and political consultants who are the gateway to conversations with any moderately relevant politician portray some sort of unchangeable consensus in support of the punishment bureaucracy that dooms all possible changes to it, making futile the project of significant change. They use this general cloud of ignorant cynicism to consolidate support for the establishment, discredit dissent, and demoralize, deflate, and depoliticize people who might want to lead struggles to make the world better.

It’s revealing that even with all of these caveats about polling, the polling on investments in systems of care consistently for decades prevail over investments in the punishment bureaucracy. Let’s put this myth about “popularity” to bed once and for all.

Alec’s Copaganda Newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Alec’s Copaganda Newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In a sinister move, pundits often respond to arguments seeking small reductions in the punishment bureaucracy as if the proponent is suggesting immediately removing all police and prisons. I have not found a single source in mainstream news in which someone takes on the argument about why a local budget should not, say, shift 10-20% of the police/jail budget to community-based services as a starting point, especially because those bureaucracies are so bloated that such reductions can be done, as the Seattle police proposed, without even altering their core operations. So, almost every public conversation avoids meaningful dialogue about specific incremental policy suggestions to shift public investments by ignoring actual proposals and shouting fearmongering distractions.

I talk to a lot of people across all walks of life in my work, including lots of prosecutors, police, crime survivors, and people accused of crimes. But the group that most bewilders me on a consistent basis is the professional liberal intellectual. In Copaganda, I discussed Jacques Ellul’s seminal scholarship about modern propaganda, in which he found that the liberal intellectual across all post-World War II societies is the most susceptible of anyone to certain forms of propaganda because they: a) consume the most mass-produced news; b) feel the need to express an opinion about everything; and c) have a lot of hubris such that they think they are smart enough for propaganda to not work on them. But even knowing this, I am constantly surprised in my daily life at the levels of ignorance among Smart People who consume a lot of news. Many people are so propagandized, defensive, and emotional that they are unable to assess what they know and do not know, hear new information, or question their own assumptions with humility and generosity. Any challenge to the punishment bureaucracy simply does not compute precisely because it goes against “conventional wisdom” that is taken as so obvious that anyone questioning it is not to be treated seriously. Many pundits, like Matt Stoller—who is a vociferous critic of corporate monopoly—are also unable to develop an analogous structural analysis that they are perfectly able to marshal in other contexts.

I don’t know Matt Stoller personally, but we have some mutual friends, and it’s important not to confuse my judgment that the things he’s saying publicly are ill-considered and dangerous with attacks on him as a person. He seems like a smart person with some good things to say about antitrust, and I’m hoping that in the future he will resist the urge to comment confidently in public about police, prosecutors, and prisons without taking the time to learn about them or at least without expressing some uncertainty or more humility about the assumptions and empirical questions underlying his commentary. The same should be understood about my criticisms of the Atlantic and ProPublica’s Alec MacGillis or Heather Knight at the New York War Crimes. I hope to get the chance to talk to Matt and people who share his views about public safety more because it takes a long time to unpack the fearful emotions and conventional intuitions that Copaganda instills in us. The success or failure of an anti-fascist coalition will depend in part on whether more people of influence take an honest look at (and make a good faith effort to learn about) the way the repressive bureaucracies of the state—and the large monopolies parasitic on them—actually function. I have benefited from conversations with knowledgeable people in many other areas who have helped me see what I don’t know and helped me grasp how many of my prior assumptions and beliefs have been wrong over the course of my adult life. It’s important to do much more of this kind of conversation—preferably with people willing to listen—because providing examples of this kind of dialogue is the kind of thing that can help many people begin to understand the scope of what is being kept from them. And, in our own lives, we must open up our hearts and minds however much we are able to people who have been so thoroughly copagandized that discussion with them feels futile at first.

From Alec’s Copaganda Newsletter via this RSS feed