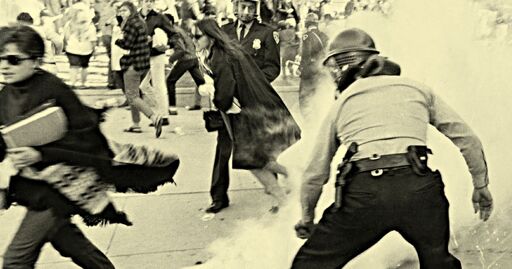

Photo: The The Capital Times/University of Wisconsin-Madison

Photo: The The Capital Times/University of Wisconsin-Madison

The social unrest that used to be called “the long hot summer” goes on all year round now, 24/7, but even by the whiplash standards of Trump II, it was a hectic news cycle. It was June, and $2 billion B-2 bombers were dropping bunker busters on Iran, setting off what some imagined to be the opening rounds of World War III. In Minnesota, a state representative and her husband had just been shot dead in their home; a state senator and his wife had been shot and injured. Out in L.A., home to the Zoot Suit Riots, Watts, and Rodney King, hundreds were protesting ICE, whose agents were snatching up allegedly undocumented day laborers and street vendors — even a union leader — and sending them off to parts unknown. In response, Trump brought in the National Guard — against the wishes of the governor, the first time a president had done so since 1965 — as well as 700 Marines, lest Tinseltown be “burned to the ground.”

Meanwhile, across the country, the opposition was ramping up. Millions more protesters were taking to the streets, declaring June 14, Trump’s birthday, to be “No Kings Day,” waving homemade signs, chanting slogans, summoning slivers of hope. On a subway platform in Brooklyn, a crowd waiting to go to a rally spontaneously broke into a chorus of “This Land Is Your Land,” the song Woody Guthrie used to play on his guitar with THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS written on the body. The struggle for what America is, what it might become, was back on. As many had come to believe, the future was at stake.

For me, currently a 77-year-old New York grandpa who doesn’t quite bend in all the places he used to, the situation had its familiarities. Like so many of my famous, once dominant, now dwindling generation, I’d been to plenty of protests. It was what our crew did back in our youth, a coming-of-age ritual that for me began on an early morning in 1965 in front of the Flushing draft board.

Photo: Neil Haworth/War Resisters League

Photo: Neil Haworth/War Resisters League

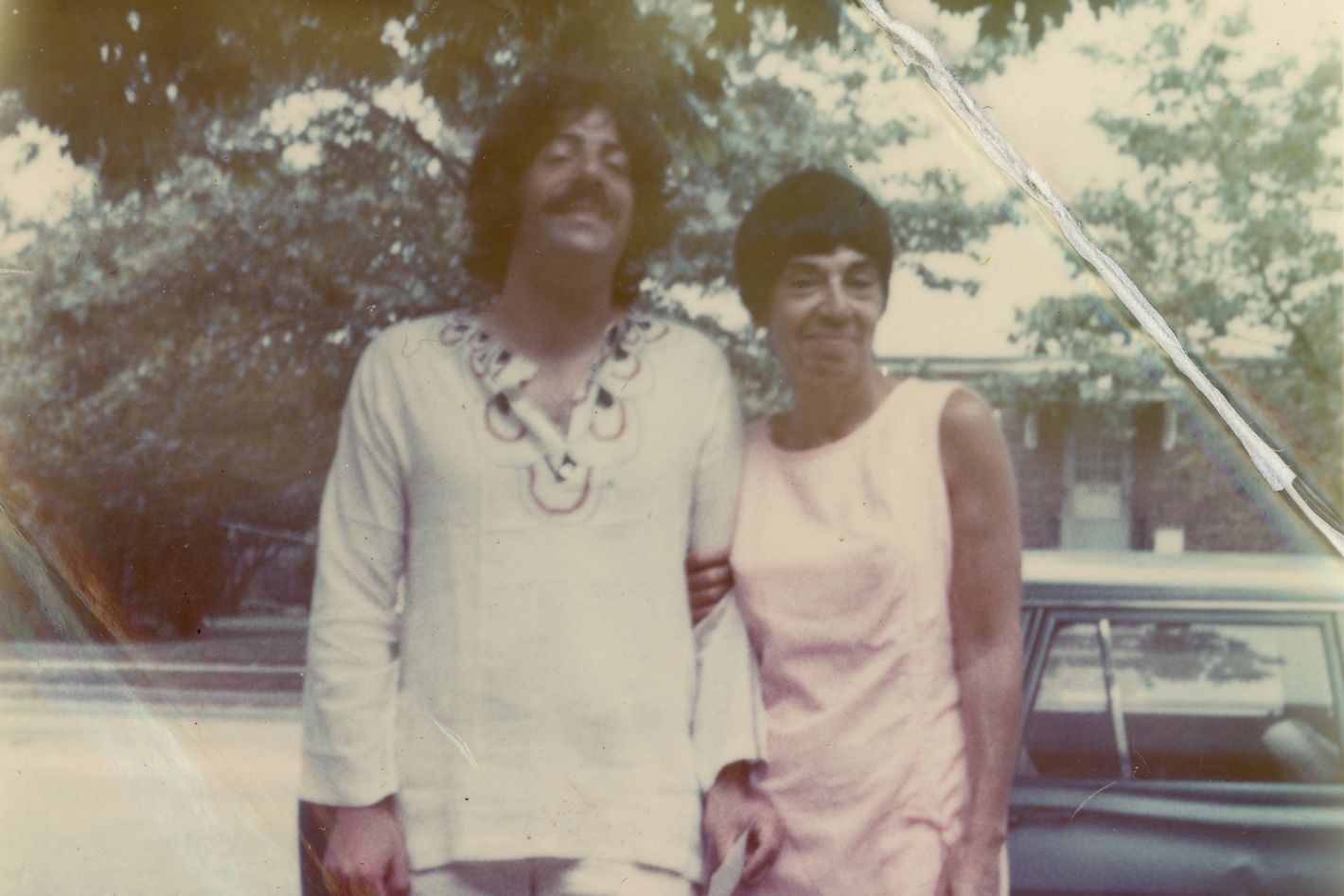

Photo: Courtesy Mark Jacobson

Photo: Courtesy Mark Jacobson

Photo: Duane Hopp/University of Wisconsin-Madison

Photo: Duane Hopp/University of Wisconsin-Madison

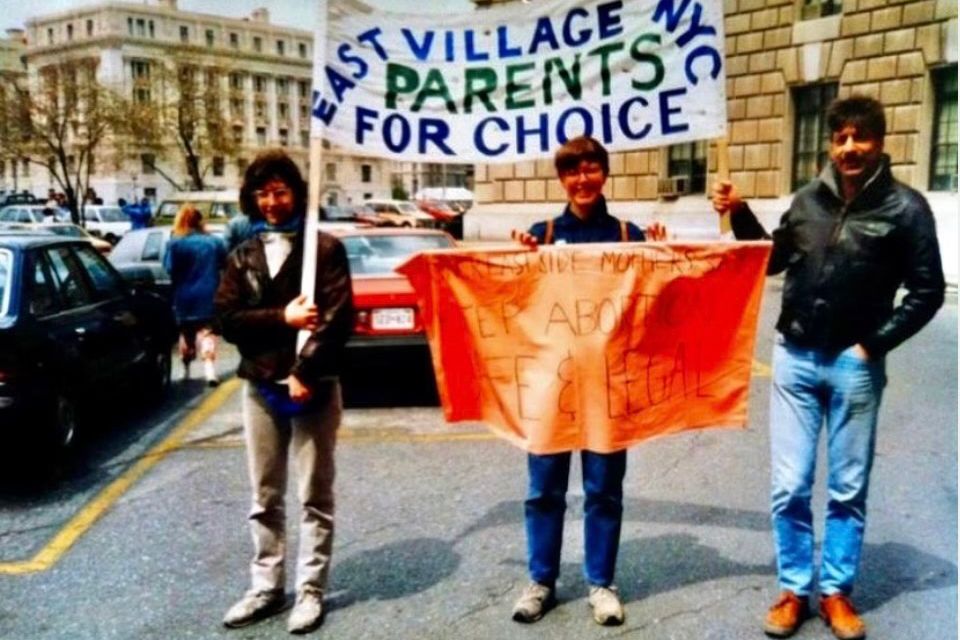

Photo: Courtesy Mark Jacobson

Photo: Courtesy Mark Jacobson

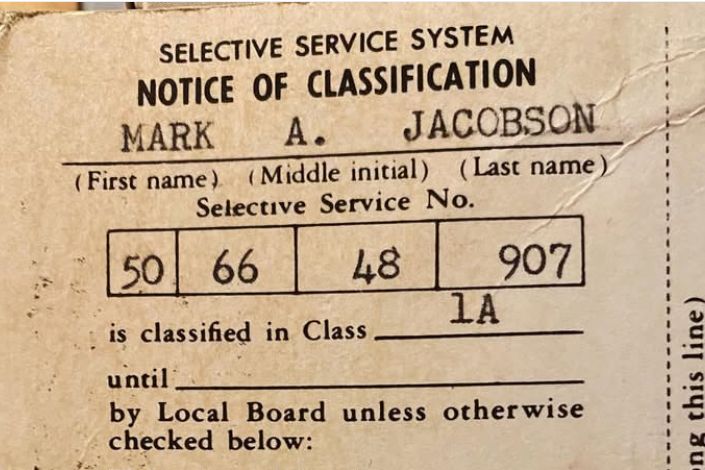

At the start of ’65, Vietnam was not yet a full-on ground war for the Americans, not officially, but there was no secret which way that wind was blowing. In February, the Viet Cong guerrillas launched a surprise attack near Pleiku, killing eight Americans. General William Westmoreland, the U.S. commander (later, we called him “General Wastemoreland”), was lobbying President Lyndon Johnson to escalate the conflict into an all-out war against Ho Chi Minh’s Communist government. Back home, the antiwar movement was gearing up. In Union Square, several young men set fire to their draft cards, a federal offense. As 17-year-old seniors at Francis Lewis High School, located on the misnomered Utopia Parkway, we had no draft cards to burn. But they were on the way, set to drop like stones through our parents’ mail slots on our 18th birthdays. That was when we would receive our first “classification,” a rubric that ran from 4-F, or “not qualified” (unfit for service), to the dreaded 1-A, which qualified you for active duty, i.e., potential cannon fodder.

For many of us, this was the first time we had awaited an event that could affect the rest of our lives. Sure, most of us had been bar mitzvahed, declared “men” by bearded rabbis from Europe. But this was a joke. Maybe in the past, like when crossing the desert ahead of the Egyptians or working in a Brownsville candy store in 1934, it made sense for Jewish boys to become men at age 13. But this was Fresh Meadows, NYC, a bucolic promised land with the recently built Long Island Expressway running through it. We were not men but the sniffy little teenage princes of our parents’ relentlessly optimistic dreams of assimilation, which for me and my junior-bohemian crew meant long hours of listening to scratchy recordings of Mississippi bluesmen, watching Luis Buñuel movies at the New Yorker Theater, and smoking pot in the shadowy groves of Alley Pond Park, seeds popping like tiny fireworks of enlightenment. It was an apprenticeship to being freethinking intellectuals, the kind of men we aspired to be, which had zero to do with John Wayne’s blood-and-guts version. A whole world was breaking open before our eyes, and hell no, we didn’t want to go, not to a shitshow like Vietnam.

I asked my father about it. Born in 1920, one generation of big-city immigrants ahead of me, Dad had been to war, fought the Nazis. Assigned to the 133rd Engineer Battalion, under the command of General George Patton, he built bridges in advance of the front lines, cleared minefields. Once, he told me, they tried to make him a lieutenant, but he refused, choosing to stay a lowly private first class. “All the lieutenants were getting killed,” Dad said. He didn’t have to prove how brave he was; simply being there, doing his job, was enough. This was what his generation of immigrants did: enlist to fight for the country that had taken them in, risk everything if need be. It was a testament of irrevocable citizenship, skin in the game, something even the Klan couldn’t take away. The fact that the Nazis were the enemy was just icing on the cake.

But what about me? I asked my father. What should I do? Protesting the war was a matter of conscience, I told him as we rode along Union Turnpike, laying out my teenage argument, about the inequity of American imperialism and the right of all people to self-determination, which I’d learned going to lefty “teach-ins” given by people like A. J. Muste and Dr. Spock with my high-school buddies.

What would he do? I asked my father, slayer of Nazis. Dad shook his head. He’d purchased our house, a corner lot, no less, with schools for me and my sister within walking distance, for $18,000 with a GI Bill loan. It was a square deal, showed the nation had welcomed us into the fold. But this was a different time, a different war. Dad didn’t really know. I was turning 18, almost grown. It was my decision to make.

So it was, with Barry McGuire’s recording of “Eve of Destruction” on the radio saying soon enough we’d be “old enough to kill but not for votin’,” that half a dozen of us went off to protest at the draft board in Flushing.

Our spiritual leader was Matty Weinstein, he of the sunburst Jew-fro, first-board player on the Lewis chess team, always with a list of books we had to read, doorstops like John Barth’s post-modernist The Sot-Weed Factor. We believed in Lenin’s 1922 directive that “of all the arts, the most important for us is the cinema,” so in case the Flushing draft protest were to become history, as we were sure it would, we headed up to the roof of the building with our windup Bell & Howell to get a panoramic shot.

We were up there only a couple of minutes before the cops appeared. It hadn’t been long since the JFK assassination; they had to check. But these weren’t today’s body-armored SWAT-team warriors. Still puffing from climbing the stairs, they might as well have stepped out of an episode of Car 54, Where Are You?

“What are you kids doing up here?” they wanted to know.

Matty told us not to worry. “I’ll show them my SDS card,” he said, referring to Students for a Democratic Society, then a relatively new antiwar group he’d joined. To possess an SDS card certified that we had just as much right to be on that rooftop as the cops, Matty assured us — that we belonged there.

The cops gave the card a cursory look, handed it back, told us to get our shots and scat. Clearly, they’d never heard of SDS or its founding document, The Port Huron Statement, originally drafted by one of the organization’s leaders, Tom Hayden, who would marry Jane Fonda, daughter of Henry. “We are the people of this generation,” the 1962 manifesto began, “bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we are to inherit.”

The cops didn’t know that, just as they didn’t know that, soon enough, officers just like them would be taping plastic daffodils to their nightsticks as a mocking symbol of “flower power” and beating hippies senseless. Show them your SDS card then and they would hit you again, haul you off to the Tombs. The cops couldn’t know that, and neither could we. That’s because, in 1965, so much of it hadn’t happened yet: the My Lai Massacre, the secret war in Cambodia, the helicopters hauling ass from Saigon rooftops. The deaths of more than 58,000 Americans and more than a million Vietnamese. The whole sad story.

Photo: Courtesy Mark Jacobson

Photo: Courtesy Mark Jacobson

Sixty years after that Flushing day, as the harsh winter of 2025 slid into an even harsher spring, I found myself standing in front of the Tesla dealership by the mucky shores of the Gowanus Canal holding up my homemade sign: ELON MUSK’S FUTURE DOES NOT INCLUDE YOU — NO ÜBERMENSCHEN!

The Tesla Resistance, as we called it, had become an appointment protest for the wife and me back in those early days of the MAGA Restoration, when it appeared that Trump and Musk had fused together, like Ray Milland and Rosey Grier in the 1972 B-movie The Thing With Two Heads, a monster merge of private wealth and state power. What had always been true behind closed doors was now out in the open, unashamedly stalking the land with whirring chain saw and heedless bombast, bent on reordering society to fit its insatiable desires.

Each Saturday morning, like two little Davids, the wife and I walked the seven blocks down the hill from our well-heated, nearly paid-off Park Slope rowhouse to join the 200 or so mostly gray-ponytailed and polar-fleece-clad geezer dissenters assembled in front of the sleek new Tesla dealership located under the rattling trestle of the F train. Each protester outfitted with homemade, witty-adjacent anti-Musk signs such as GO STEAL DATA ON MARS! and P.S. YOUR LOGO LOOKS LIKE AN IUD, our praxis was simple. When people in passing vehicles honked their horns to show support, we cheered. When drivers of buses and cement mixers honked, we cheered louder because working-class outreach is always paramount to the struggle.

And, of course, we chanted. Once, there was real j’accuse to refrains like “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” Now you have to grit your dental implants as NPR listeners, former Dead Heads, and worse — many of them home-owners (like us) in one of the highest-priced neighborhoods of an infamously unaffordable city — go into the standard call-and-response: “Tell me what does democracy looks like!” “This is what democracy looks like!” (You know, how about “This is what late-stage capitalism looks like”?) The demo went on like this from noon to two, when, like Unitarians at prayer, we’d exchange comradely handshakes, put our signs into the recycling bin, and go home, vowing to keep up the fight next week.

True, the Tesla Resistance didn’t have the revolutionary romance of yesteryear: running through tear gas at the U of Wisconsin Dow Chemical demo (it made napalm) hand in hand with my then-girlfriend, Judy, who would soon leave me for a history grad student and break my heart. It didn’t have the grit of the People’s Park sieges in Berkeley in ’69, getting kicked in the stomach by Alameda County sheriff’s deputies on the way to the Santa Rita jail, throwing debris at the Northside home of H-bomb avatar Edward Teller. It didn’t even offer the thrill of marching across the Brooklyn Bridge during Occupy Wall Street and seeing the beacon of the 99 percent beamed onto the blank corporate slab of the Verizon Building, proclaiming ANOTHER WORLD IS POSSIBLE.

But what was the rampart-grizzled septuagenarian to do? Like it or not, the times were the times, the crowd was the crowd. The present-day resistance might not have been all that, but neither were we.

Truth be told, my protesting had fallen off since the Women’s March in 2017. At the time, it was the most-attended one-day protest in American history. Given the turnout, the expectation was that Trump, inaugurated only the day before, would make a comment, perhaps offer a small conciliatory gesture. Even Richard Nixon, Tricky Dick himself, unable to sleep early on the morning of May 9, 1970, five days after four Kent State students were killed by the National Guard, decided to take a 4 a.m. stroll to the Lincoln Memorial, where he told astounded, sleepy hippies that he knew that they hated the war but hoped it wouldn’t “turn into a bitter hatred of our country and everything it stands for.” Nixon continued, “Most of you, I know, think I’m an SOB. But I want you to know that I understand just how you feel.”

Donald Trump was no Richard Nixon. His lack of even an ounce of empathy or understanding was a pivotal moment in my protest history. Trump was a brick wall, an equally repellent and hypnotically attracting force that you could despise but do little about. Why protest if you know nothing is going to change?

The years take their toll. In 2014, we took the Staten Island Ferry to protest the death of Eric Garner, strangled by the NYPD, just as we turned out for Yusef Hawkins, Sean Bell, Trayvon Martin, Amadou Diallo, Abner Louima, and Patrick Dorismond. By the time George Floyd was killed, however, with the pandemic on and friends dropping like flies, it was easier to just stay home.

The Tesla Resistance brought us back, cut through the learned apathy, the frustrating day-to-day craziness. For me, it was personal. When you’re a Fresh Meadows boy, growing up a Schwinn ride away from the Trump family’s 23-room columned home in Jamaica Estates, the snoot-bag neighborhood where my dad often moonlighted as a carpenter, it is hard for it to not be personal. There were always guys like Trump around when we were in high school, pricks who thought they owned the world. Now, with his second coming, I can’t help but feel that Trump is targeting me specifically, seeking to dismantle everything I ever loved about my middle-class-striver upbringing, sucking the life out of whatever was left of the public sector in which my parents and everyone else I knew worked, squashing the immigrant hustle to which I attribute whatever success I’ve had. That he’s against what I love about my New York home: feral street life, literacy, and the democratic ideal that everyone on the subway has a story to tell at least as interesting as your own.

Tactically speaking, if you wanted to call attention to the internal contradictions of the MAGA beast, it made good sense to bring the Tesla Resistance to the Gowanus Canal. Completed in 1869, the canal was built to serve the thriving Brooklyn industrial base but fell into disuse during the mid-20th century, becoming one of the most polluted bodies of water in the country. It was declared a Superfund site in 2010. With several of the brick factory buildings still standing, the area seemed a perfect candidate for the MAGA fantasy of the return of U.S. manufacturing. But, of course, the site is being redeveloped for luxury high-rises marketed as waterfront property.

Logistically, in early 2025, it made sense to target Musk. A whacked-out cultist demented enough to think himself indispensable, showing up at the White House in a black MAGA hat when everyone else wore red, Musk was always going to be the weaker head of the dragon. Trump was a demigod, a force of nature. For all his wealth, Musk was still a guy pushing fey electric cars named after a freaky Serbian scientist when the American he-man preferred the thrust of internal combustion. He was a former weird-kid sci-fi fan who thought it would be cool to go to space and live in a bubble when half the internet, Trump voters included, knew for a fact that the Apollo moon landing had been faked.

Then there was the Cybertruck, Musk’s gamer-angled entry into the pickup market. While the regular Tesla sedan was common in areas like Park Slope as a sensible climate-conscious luxury vehicle, the Cybertruck, reminiscent of the Casspir, the tanklike, mine-resistant vehicle used extensively by apartheid police in Musk’s native South Africa, struck a decidedly different note.

That might have been the point this past New Year’s Morning, when Green Beret master sergeant Matthew Livelsberger, a decorated hero with 19 years of service, drove a rented Cybertruck into the driveway of the Trump International Hotel in Las Vegas and shot himself in the head as the truck exploded into a fireball. Captured on CCTV, the explosion made a hell of a video, flames lurching through the sun roof, the Trump logo looming in the background. For the old marcher, the image summoned up the famous photo of the Buddhist monk Thích Quang Đuc setting himself on fire on a Saigon street in 1963 in protest of the American-sponsored South Vietnamese government. The video of the burning Cybertruck at Trump’s hotel had some of that power, even if it was soon buried by the news cycle. A similar act by Aaron Bushnell, a senior airman in the USAF who set himself on fire in front of the Israeli Embassy in Washington, D.C., to protest the war in Gaza, also quickly disappeared amid the Darwinian struggle for public attention.

Still, it could be said that the Tesla Resistance was a modest success. Tesla stock did tank, Musk was soon beheaded, cast out. Small victories could be won simply by showing up. As for the rest of it — the day-to-day drumbeat of mendacity, the supersizing of ICE, the still functioning DOGE, the slashing of Medicaid, the gutting of education and everything that might benefit anyone who isn’t rich, etc. etc. — that goes on and on.

Photo: William L.Rukeyser/Getty Images

Photo: William L.Rukeyser/Getty Images

Photo: Jason Green/Getty Images

Photo: Jason Green/Getty Images

Photo: Jessica Rinaldi/Reuters

Photo: Jessica Rinaldi/Reuters

Photo: Courtesy Mark Jacobson

Photo: Courtesy Mark Jacobson

We’ve been thinking about our roles, the wife and I, where we fit in now, how it is not about us anymore but rather about those who are going to have to live with this mess, so much of it created on our watch. What matters now is the offspring, we tell ourselves, how the country will be for them. We’re not so worried about our children. The three of them, all grown-ups in their 30s and beyond, are well schooled, clear-eyed, and totally capable of dealing with whatever Trump, J. D. Vance, and the rest of their zombie crew dish out. But now there is the grandchild, the next iteration of us, the sublime Alice. Only 7, she’s already an excellent big-city kid, at home on the train, reading a million books, able to tell a joke, a steadfast adherent of the flickering Enlightenment. Clearly: one of us. It is her we worry about, the world as she’ll find it.

For the old protester, that’s what it comes down to, all these years of screaming and yelling, sides taken and abandoned: the need to speak up, not to give into the oppressive algorithm of inaction. For me, the fight against Trump has the immediacy I felt all those years ago at the Flushing draft board. There is no choice but to be there, whether the results are immediately perceptible or not. That doesn’t mean you have to be an all-purpose protester. Of late, several long-time friends have been after me to publicly protest the terrible situation in Gaza. I believed that the Israelis were acting horrifically, didn’t I? Yes, I did. Absolutely. The situation is heartbreaking. But as a New York Jew who was born on May 12, 1948, two days prior to the establishment of the State of Israel, with a family not so long ago out of the shtetl, my feelings cannot be condensed into a cardboard sign or a chant. It is a private matter for me, to be worked out within.

This brings me back to an evening in 2003 my wife and I spent in my mother’s apartment on Bell Boulevard, where she moved after my dad’s death in 1995. Mom had always been indefatigable, but my father’s demise energized her even more. In rapid succession, she became the president of the garden club, the treasurer of the quilting club, the curator of the film club. It was after one of these activities, a 16-mm. showing of The Producers in the basement rec room (Zero Mostel’s niece lived in the building), that the wife and I sat down for a bissel coffee cake with “the girls,” almost all of them widows in their late 70s and 80s. One of the ladies, Evelyn, took me aside. Since she’d heard my mother talk about the stories her wonderful son had written about cops and robbers over the years, she had a question.

“Do you know where I can get a gun?” she wanted to know.

“A gun? What do you want a gun for?” Deep into her 80s, about four-foot-ten and shrinking, Evelyn lowered her voice to a whisper. “I’m going to shoot George Bush,” she said.

She hated Bush. An old peacenik, she knew people who had died in 9/11 and was appalled at the way Bush had used the attack as an excuse to pass the Patriot Act and invade Iraq. He deserved to die.

But there was no reason a young person should have to do it, Evelyn said. “They’ve got their whole lives in front of them. It isn’t worth it. An old person should do it. So I get caught? Big deal. What are they going to give me? Life?” Maybe she’d do it and maybe she wouldn’t, Evelyn said. “But an old lady can dream.”

Sure, you could dream.

Photo: Courtesy Mark Jacobson

Photo: Courtesy Mark Jacobson

On No Kings Day, we needed a sign. We’d already gone with GLEEFUL SADISTS MAKE BAD LEADERS, so that was out. The wife left the room and came back with an American flag. “Here’s our sign,” she said.

So there we were, marching down Fifth Avenue again — just as we had two months earlier for the “Hands Off” demo — in the pouring rain, holding our flag, the same one we’d pledged allegiance to, hands over our hearts, every morning in grammar school. It was a change from back in the day, when, besides the upside-down banner indicating distress, you rarely saw an American flag at protests. It had always been tactically dumb: ceding the national colors to the other side. Now was the time to take them back.

It wasn’t long before we recognized what Old Glory could do for us, the protection it provided. At 37th Street or so, the drones were hovering, surveilling like a gnat fleet of tiny panopticons. We’d been warned about this by the ACLU: The NYPD, the Feds, and who knew who else would be up there, adding to their facial-recognition files.

Without the recommended masks, we raised the flag, hid under the Stars and Stripes. It felt a little corny, shielding ourselves with the flag, but it was honest, too. It clicked in. The threat was real. It was time to stand up for America: not an America you unconditionally loved, necessarily, but an America you could live with.

More From Mark Jacobson

The Anxiety of AgeHow Will New York Remember the Subway Shooter?New York’s Underworld Is World Class

From Intelligencer - Daily News, Politics, Business, and Tech via this RSS feed