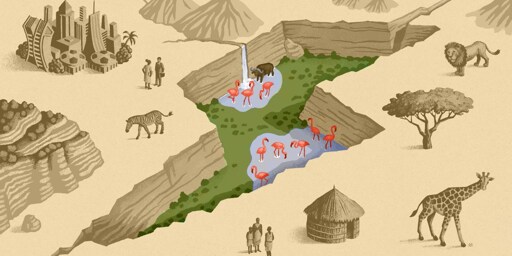

The earth around Lake Naivasha, a shallow freshwater basin in south-central Kenya, does not seem to want to lie still.

Ash from nearby Mount Longonot, which erupted as recently as the 1860s, remains in the ground. Obsidian caves and jagged stone towers preside over the steam that spurts out of fissures in the soil and wafts from pools of boiling-hot water—produced by magma that, in some areas, sits just a few miles below the surface.

It’s a landscape born from violent geologic processes some 25 million years ago, when the Nubian and Somalian tectonic plates pulled apart. That rupture cut a depression in the earth some 4,000 miles long—from East Africa up through the Middle East—to create what’s now called the Great Rift Valley.

This volatility imbues the land with vast potential, much of it untapped. The area, no more than a few hours’ drive from Nairobi, is home to five geothermal power stations, which harness the clouds of steam to generate about a quarter of Kenya’s electricity. But some energy from this process escapes into the atmosphere, while even more remains underground for lack of demand.

That’s what brought Octavia Carbon here.

In June, just north of the lake in the small but strategically located town of Gilgil, the startup began running a high-stakes test. It’s harnessing some of that excess energy to power four prototypes of a machine that promises to remove carbon dioxide from the air in a manner that the company says is efficient, affordable, and—crucially—scalable.

In the short term, the impact will be small—each device’s initial capacity is just 60 tons per year of CO2—but the immediate goal is simply to demonstrate that carbon removal here is possible. The longer-term vision is far more ambitious: to prove that direct air capture (DAC), as the process is known, can be a powerful tool to help the world keep temperatures from rising to ever more dangerous levels.

“We believe we are doing what we can here in Kenya to address climate change and lead the charge for positioning Kenya as a climate vanguard,” Specioser Mutheu, Octavia’s communications lead, told me when I visited the country last year.

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has stated that in order to keep the world from warming more than 1.5 °C over preindustrial levels (the threshold set out in the Paris Agreement), or even the more realistic but still difficult 2 °C, it will need to significantly reduce future fossil-fuel emissions—and also pull from the atmosphere billions of tons of carbon that have already been released.

Some argue that DAC, which uses mechanical and chemical processes to suck carbon dioxide from the air and store it in a stable form (usually underground), is the best way to do that. It’s a technology with immense promise, offering the possibility that human ingenuity and innovation can get us out of the same mess that development caused in the first place.

Last year, the world’s largest DAC plant, Mammoth, came online in Iceland, offering the eventual capacity to remove up to 36,000 tons of CO₂ per year—roughly equal to the emissions of 7,600 gas-powered cars. The idea is that DAC plants like this one will remove and permanently store carbon and create carbon credits that can be purchased by corporations, governments, and local industrial producers, which will collectively help keep the world from experiencing the most dangerous effects of climate change.

Climeworks’ Mammoth carbon removal plant near Reykjavik, Iceland.

JOHN MOORE/GETTY IMAGES

Now, Octavia and a growing number of other companies, politicians, and investors from Africa, the US, and Europe are betting that Kenya’s unique environment holds the keys to reaching this lofty goal—which is why they’re pushing a sweeping vision to remake the Great Rift Valley into the “Great Carbon Valley.” And they hope to do so in a way that provides a genuine economic boost for Kenya, while respecting the rights of the Indigenous people who live on this land. If they can do so, the project could not just give a needed jolt to the DAC industry—it could also provide proof of concept for DAC across the Global South, which is particularly vulnerable to the ravages of climate change despite bearing very little responsibility for it.

But DAC is also a controversial technology, unproven at scale and wildly expensive to operate. In May, an Icelandic news outlet published an investigation into Climeworks, which runs the Mammoth plant, finding that it didn’t even pull in enough carbon dioxide to offset its own emissions, let alone the emissions of other companies.

Critics also argue that the electricity DAC requires can be put to better use cleaning up our transportation systems, heating our homes, and powering other industries that still rely largely on fossil fuels. What’s more, they say that relying on DAC can give polluters an excuse to delay the transition to renewables indefinitely. And further complicating this picture is shrinking demand from governments and corporations that would be DAC’s main buyers, which has left some experts questioning whether the industry will even survive.

Carbon removal is a technology that seems always on the verge of kicking in but never does, says Fadhel Kaboub, a Tunisian economist and advocate for an equitable green transition. “You need billions of dollars of investment in it, and it’s not delivering, and it’s not going to deliver anytime soon. So why do we put the entire future of the planet in the hands of a few people and a technology that doesn’t deliver?”

Layered on top of concerns about the viability and wisdom of DAC is a long history of distrust from the Maasai people who have called the Great Rift Valley home for generations but have been displaced in waves by energy companies coming in to tap the land’s geothermal reserves. And many of those remaining don’t even have access to the electricity generated by these plants.

Maasai men walk along the road beside the Olkaria geothermal plant.

REDUX PICTURES

It’s an immensely complicated landscape to navigate. But if the project can indeed make it through, Benjamin Sovacool, an energy policy researcher and director of the Boston University Institute for Global Sustainability, sees immense potential for countries that have been historically marginalized from climate policy and green energy investment. Though he’s skeptical about DAC as a near-term climate solution, he says these nations could still see big benefits from what could be a multitrillion-dollar industry.

“[Of] all the technologies we have available to fight climate change, the idea of reversing it by sucking CO2 out of the air and storing it is really attractive. It’s something even an ordinary person can just get,” Sovacool says. “If we’re able to do DAC at scale, it could be the next huge energy transition.”

But first, of course, the Great Carbon Valley has to actually deliver.

Challenging the power dynamic

The “Great Carbon Valley” is both a broad vision for the region and a company founded to shepherd that vision into reality.

Bilha Ndirangu, a 42-year-old MIT electrical engineering graduate who grew up in Nairobi, has long worried about the impacts of climate change on Kenya. But she doesn’t want the country to be a mere victim of rising temperatures, she tells me; she hopes to see it become a source of climate solutions. So in 2021, Ndirangu cofounded Jacob’s Ladder Africa, a nonprofit with the goal of preparing African workers for green industries.

COURTESY OF BILHA NDIRANGU

COURTESY OF BILHA NDIRANGU

She also began collaborating with the Kenyan entrepreneur James Irungu Mwangi, the CEO of Africa Climate Ventures, an investment firm focused on building and accelerating climate-smart businesses. He’d been working on an idea that spoke to their shared belief in the potential for the country’s vast geothermal capacity; the plan was to find buyers for Kenya’s extra geothermal energy in order to kick-start the development of even more renewable power. One energy-hungry, climate-positive industry stood out: direct air capture of carbon dioxide.

The Great Rift Valley was the key to this vision. The thinking was that it could provide the cheap energy needed to power affordable DAC at scale while offering an ideal geology to effectively store carbon deep underground after it was extracted from the air. And with nearly 90% of the country’s grid already powered by renewable energy, DAC wouldn’t be siphoning power away from other industries that need it. Instead, attracting DAC to Kenya could provide the boost needed for energy providers to build out their infrastructure and expand the grid—ideally connecting the roughly 25% of people in the country who lack electricity and reducing scenarios in which power has to be rationed.

“This push for renewable energy and the decarbonization of industries is providing us with a once-in-a-lifetime sort of opportunity,” Ndirangu tells me.

So in 2023, the pair founded Great Carbon Valley, a project development company whose mission is attracting DAC companies to the area, along with other energy-intensive industries looking for renewable power.

It has already brought on high-profile companies like the Belgian DAC startup Sirona Technologies, the French DAC company Yama, and Climeworks, the Swiss company that operates Mammoth and another DAC plant in Iceland (and was on MIT Technology Review’s 10 Breakthrough Technologies list in 2022, and the list of Climate Tech Companies to Watch in 2023). All are planning on launching pilot projects in Kenya in the coming years, with Climeworks announcing plans to complete its Kenyan DAC plant by 2028. GCV has also partnered with Cella, an American carbon-storage company that works with Octavia, and is facilitating permits for the Icelandic company Carbfix, which injects the carbon from Climeworks’ DAC facilities.

Cella and Sirona Technologies have a pilot program in the Great Rift Valley called Project Jacaranda.

SIRONA TECHNOLOGIES

“Climate change is disproportionately impacting this part of the world, but it’s also changing the rules of the game all over the world,” Cella CEO and cofounder Corey Pattison tells me, explaining the draw of Mwangi and Ndirangu’s concept. “This is also an opportunity to be entrepreneurial and creative in our thinking, because there are all of these assets that places like Kenya have.”

Not only can the country offer cheap and abundant renewable energy, but supporters of Kenyan DAC hope that the young and educated local workforce can supply the engineers and scientists needed to build out this infrastructure. In turn, the business could open opportunities to the country’s roughly 6 million un- or under-employed youths.

“It’s not a one-off industry,” Ndirangu says, highlighting her faith in the idea that jobs will flow from green industrialization. Engineers will be needed to monitor the DAC facilities, and the additional demand for renewable power will create jobs in the energy sector, along with related services like water and hospitality.

“You’re developing a whole range of infrastructure to make this industry possible,” she adds. “That infrastructure is not just good for the industry—it’s also just good for the country.”

The chance to solve a “real-world issue”

In June of last year, I walked up a dirt path to the HQ of Octavia Carbon, just off Nairobi’s Eastern Bypass Road, on the far outskirts of the city.

The staffers I met on my tour exuded the kind of boundless optimism that’s common in early-stage startups. “People used to write academic articles about the fact that no human will ever be able to run a marathon in less than two hours,” Octavia CEO Martin Freimüller told me that day. The Kenyan marathon runner Eliud Kipchoge broke that barrier in a race in 2019. A mural of him features prominently on the wall, along with the athlete’s slogan, “No human is limited.”

“It’s impossible, until Kenya does it,” Freimüller added.

In June, Octavia started testing its technology in the field in a pilot project in Gilgil.

OCTAVIA CARBON

Although not an official partner of Ndirangu’s Great Carbon Valley venture, Octavia aligns with the larger vision, he told me. The company got its start in 2022, when Freimüller, an Austrian development consultant, met Duncan Kariuki, an engineering graduate from the University of Nairobi, in the OpenAir Collective, an online forum devoted to carbon removal. Kariuki introduced Freimüller to his classmates Fiona Mugambi and Mike Bwondera, and the four began working on a DAC prototype, first in lab space borrowed from the university and later in an apartment. It didn’t take long for neighbors to complain about the noise, and within six months, the operation had moved to its current warehouse.

That same year, they announced their first prototype, affectionately called Thursday after the day it was unveiled at a Nairobi Climate Network event. Soon, Octavia was showing off its tech to high-profile visitors including King Charles III and President Joe Biden’s ambassador to Kenya, Meg Whitman.

Three years later, the team has more than 40 engineers and has built its 12th DAC unit: a metal cylinder about the size of a large washing machine, containing a chemical filter using an amine, an organic compound derived from ammonia. (Octavia declined to provide further details about the arrangement of the filter inside the machine because the company is awaiting approval of a patent for the design.)

Octavia relies on an amine absorption method similar to the one used by other DAC plants around the world, but its project stands apart—having been tailored to suit the local climate and run on more than 80% thermal energy.

OCTAVIA CARBON

Hannah Wanjau, an engineer at the company, explained how it works: Fans draw air from the outside across the filter, causing carbon dioxide (which is acidic) to react with the basic amine and form a carbonate salt. When that mixture is heated inside a vacuum to 80 to 100 °C, the CO2 is released, now as a gas, and collected in a special chamber, while the amine can be reused for the next round of carbon capture.

The amine absorption method has been used in other DAC plants around the world, including those operated by Climeworks, but Octavia’s project stands apart on several key fronts. Wanjau explained that its technology is tailored to suit the local climate; the company has adjusted the length of time for absorption and the temperature for CO2 release, making it a potential model for other countries in the tropics.

And then there’s its energy source: The device operates on more than 80% thermal energy, which in the field will consist of the extra geothermal energy that the power plants don’t convert into electricity. This energy is typically released into the atmosphere, but it will be channeled instead to Octavia’s machines. What’s more, the device’s modular design can fit inside a shipping container, allowing the company to easily deploy dozens of these units once the demand is there, Mutheu told me.

This technology is being tested in the field in Gilgil, where Mutheu told me the company is “continuing to capture and condition CO₂ as part of our ongoing operations and testing cycles.” (She declined to provide specific data or results at this stage.)

Once the CO2 is captured, it will be heated and pressurized. Then it will be pumped to a nearby storage facility operated by Cella, where the company will inject the gas into fissures underground. The region’s special geology again offers an advantage: Much of the rock found underground here is basalt, a volcanic mineral that contains high concentrations of calcium and magnesium ions. They react with carbon dioxide to form substances like calcite, dolomite, and magnesite, locking the carbon atoms away in the form of solid minerals.

This process is more durable than other forms of carbon storage, making it potentially more attractive to buyers of carbon credits, says Pattison, the Cella CEO. Non-geologic carbon mitigation methods, such as cookstove replacement programs or nature-based solutions like tree planting, have recently been rocked by revelations of fraud or exaggeration. The money for Cella’s pilot, which will see the injection of 200 tons of CO2 this year, has come mainly from the Frontier advance market commitment, under which a group of companies including Stripe, Google, Shopify, Meta, and others has collectively pledged to spend $1 billion on carbon removal by 2030.

The modular design of Octavia’s device can fit inside a shipping container, allowing the company to easily deploy dozens of these units once demand is there.

OCTAVIA CARBON

These projects have already opened up possibilities for young Kenyans like Wanjau. She told me there were not a lot of opportunities for aspiring mechanical engineers like her to design and test their own devices; many of her classmates were working for construction or oil companies, or were unemployed. But almost immediately after graduation, Wanjau began working for Octavia.

“I’m happy that I’m trying to solve a problem that’s a real-world issue,” she told me. “Not many people in Africa get a chance to do that.”

An uphill climb

Despite the vast enthusiasm from partners and investors, the Great Carbon Valley faces multiple challenges before Ndirangu and Mwangi’s vision can be fully realized.

Since its start, the venture has had to contend with “this perception that doing projects in Africa is risky,” says Ndirangu. Of the dozens of DAC facilities planned or in existence today, only a handful are in the Global South. Indeed, Octavia has described itself as the first DAC plant to be located there. “Even just selling Kenya as a destination for DAC was quite a challenge,” she says.

So Ndirangu played up Kenya’s experience developing geothermal resources, as well as local engineering talent and a lower cost of labor. GCV has also offered to work with the Kenyan government to help companies secure the proper permits to break ground as soon as possible.

In pitching the Great Carbon Valley, Ndirangu has played up Kenya’s experience developing geothermal resources, as well as local engineering talent and a lower cost of labor.

ALAMY

Ndirangu says that she’s already seen “a real appetite” from power producers who want to build out more renewable-energy infrastructure, but at the same time they’re waiting for proof of demand. She envisions that once that power is in place, lots of other industries—from data centers to producers of green steel, green ammonia, and sustainable aviation fuels—will consider basing themselves in Kenya, attracting more than a dozen projects to the valley in the next few years.

But recent events could dampen demand (which some experts already worried was insufficient). Global governments are retreating from climate action, particularly in the US. The Trump administration has dramatically slashed funding for development related to climate change and renewable energy. The Department of Energy appears poised to terminate a $50 million grant to a proposed Louisiana DAC plant that would have been partially operated by Climeworks, and in May, not long after that announcement, the company said it was cutting 22% of its staff.

At the same time, many companies that would have likely been purchasers of carbon credits—and that a few years ago had voluntarily pledged to reduce or eliminate their carbon emissions—are quietly walking back their commitments. Over the long term, experts warn, there are limits to the amount of carbon removal that companies will ever voluntarily buy. They argue that governments will ultimately have to pay for it—or require polluters to do so.

Further compounding all these challenges are costs. Critics say DAC investments are a waste of time and money compared with other forms of carbon drawdown. As of mid-December, carbon removal credits in the European Union’s Emissions Trading System, one of the world’s largest carbon markets, were priced at around $84 per ton. The average price per DAC credit, for comparison, is nearly $450. Natural processes like reforestation absorb millions of tons of carbon annually and are far cheaper (though programs to harness them for carbon credits are beset with their own controversies). Ultimately, DAC continues to operate on a small scale, removing only about 10,000 metric tons of CO2 each year.

Even if DAC suppliers do manage to push past these obstacles, there are still thorny questions coming from inside Kenya. Groups like Power Shift Africa, a Nairobi-based think tank that advocates for climate action on the continent, have derided carbon credits as “pollution permits” and blamed them for delaying the move toward electrification.

“The ultimate goal of [carbon removal] is that you can say at the end, well, we can actually continue our emissions and just recapture them with this technology,” says Kaboub, the Tunisian economist, who has worked with Power Shift Africa. “So there’s no need to end fossil fuels, which is why you get a lot of support from oil countries and companies.”

Another problem he sees is not limited to DAC but extends to the way that Kenya and other African nations are pursuing their goal of green industrialization. While Kenyan President William Ruto has courted international financial investment to turn Kenya into a green energy hub, his administration’s policies have deepened the country’s external debt, which in 2024 was equal to around 30% of its GDP. Geothermal energy development in Kenya has often been financed by loans from international institutions or other governments. As its debt has risen, the country has enacted national austerity measures that have sparked deadly protests.

Kenya may indeed have advantages over other countries, and DAC costs will most likely go down eventually. But some experts, such as Boston University’s Sovacool, aren’t quite sold on the idea that the Great Carbon Valley—or any DAC venture—can significantly mitigate climate change. Sovacool’s research has found that at best, DAC will be ready to deploy on the necessary scale by midcentury, much too late to make it a viable climate solution. And that’s if it can overcome additional costs—such as the losses associated with corruption in the energy sector, which Sovacool and others have found is a widespread problem in Kenya.

MIRIAM MARTINCIC

MIRIAM MARTINCIC

Nevertheless, others within the carbon removal industry remain more optimistic about DAC’s overall prospects and are particularly hopeful that Kenya can address some of the challenges the technology has encountered elsewhere. Cost is “not the most important thing,” says Erin Burns, executive director of Carbon180, a nonprofit that advocates for the removal and reuse of carbon dioxide. “There’s lots of things we pay for.” She notes that governments in Japan, Singapore, Canada, Australia, the European Union, and elsewhere are all looking at developing compliance markets for carbon, even though the US is stagnating on this front.

The Great Carbon Valley, she believes, stands poised to benefit from these developments. “It’s big. It’s visionary,” Burns says. “You’ve got to have some ambition here. This isn’t something that is like deploying a technology that’s widely deployed already. And that comes with an enormous potential for huge opportunity, huge gains.”

Back to the land

More than any external factor, the Great Carbon Valley’s future is perhaps most intimately intertwined with the restless earth on which it’s being built, and the community that has lived here for centuries.

To the Maasai people, nomadic pastoralists who inhabit swathes of Eastern Africa, including Kenya, this land around Lake Naivasha is “ol-karia,” meaning “ochre,” after the bright red clay found in abundance.

South of the lake is Hell’s Gate National Park, a 26-square-mile nature reserve where the region’s five geothermal power complexes—with a sixth under construction—churn on top of the numerous steam vents. The first geothermal power plant here was brought into service in 1981 by KenGen, a majority-state-owned electricity company; it was named Olkaria.

But for decades most of the Maasai haven’t had access to that electricity. And many of them have been forced off the land in a wave of evictions. In 2014, construction on a KenGen geothermal complex expelled more than 2,000 people and led to a number of legal complaints. At the same time, locals living near a different, privately owned geothermal complex 50 miles north of Naivasha have complained of noise and air pollution; in March, a Kenyan court revoked the operating license of one of the project’s three plants.

Neither Octavia or Cella is powered by output from these two geothermal producers, but activists have warned that similar environmental and social harms could resurface if demand for new geothermal infrastructure grows in Kenya—demand that could be driven by DAC.

Ndirangu says she believes some of the complaints about displacement are “exaggerated,” but she nonetheless acknowledges the need for stronger community engagement, as does Octavia. In the long term, Ndirangu says, she plans to provide job training to residents living near the affected areas and integrate them into the industry, although she also says those plans need to be realistic. “You don’t want to create the wrong expectation that you will hire everyone from the community,” she says.

That’s part of the problem for Maasai activists like Agnes Koilel, a teacher living near the Olkaria geothermal field. Despite past promises of employment at the power plants, the jobs that are offered are lower-paying positions in cleaning or security. “Maasai people are not [as] employed as they think,” she says.

The Maasai people have inhabited swathes of Eastern Africa, including Kenya, for centuries, though many still lack access to the power that’s now produced there.

ALAMY

DAC is a small industry, and it can’t do everything. But if it’s going to become as big as Ndirangu, Freimüller, and other proponents of the Great Carbon Valley hope it will be, creating jobs and driving Kenya’s green industrialization, communities like Koilel’s will be among those most directly affected—much as they are by climate change.

When I asked Koilel what she thought about DAC development near her home, she told me she had never heard of the Great Carbon Valley idea, or of carbon removal in general. She wasn’t necessarily against geothermal power development on principle, or opposed to any of the industries that might push it to expand. She just wants to see some benefits, like a health center for her community. She wants to reverse the evictions that have pushed her neighbors off their land. And she wants electricity—the same kind that would power the fans and pumps of future DAC hubs.

Power “is generated from these communities,” Koilel said. “But they themselves do not have that light.”

Diana Kruzman is a freelance journalist covering environmental and human rights issues around the world. Her writing has appeared in New Lines Magazine*,* The Intercept*,* Inside Climate News*, and other publications. She lives in New York City.*

From MIT Technology Review via this RSS feed