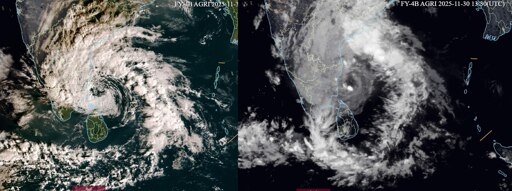

COLOMBO — Cyclone Ditwah, which claimed around 650 lives and left at least 200 people missing, cast a heavy pall of gloom over Sri Lanka from the moment it entered the island’s skies Nov. 28. By Dec. 2, the storm had finally moved on, leaving behind silence, debris and grief — but also, in some places, an unexpected calm. Along stretches of the Jaffna coast in northern Sri Lanka, the returning sunshine revealed a strange and startling sight. Thick patches of snow-like white foam had gathered along the shoreline, astonishing residents who said they had never seen anything like it before. For children, especially, the sight felt surreal. Amid a nation still mourning its losses, they ran barefoot along the beach, laughing and playing with the foam, as if it were snow. The fleeting scene offered a gentle contrast to the scale of devastation elsewhere, but it also raised questions about how the ocean responds to land-based disasters. In the aftermath of the floods, fears spread that polluted waters sweeping through industrial zones and sewage systems had contaminated the sea, and the foam was visible evidence of that pollution. Scientists, however, say the phenomenon was natural. “Such sea foam can form naturally after powerful storms and strong winds, like those experienced in Jaffna during the northeast monsoon,” said Ganapathypillai Arulananthan, former director-general of the National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency (NARA). “Rough seas churn microscopic algae and plankton, releasing organic compounds that act like natural surfactants. When waves trap…This article was originally published on Mongabay

From Conservation news via this RSS feed