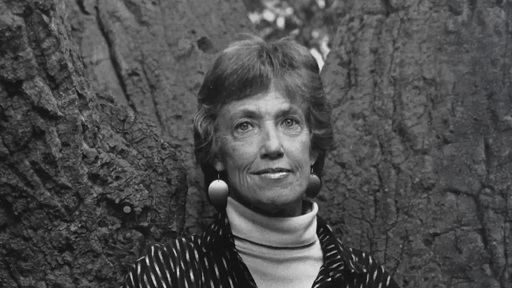

For much of the late 20th century, environmental writing oscillated between alarm and reassurance. One strand emphasized catastrophe; another urged optimism. A smaller, more demanding tradition insisted on neither denial nor consolation, but attention. It asked what it meant to remain fully present to ecological loss without turning away or hardening into fatalism. That question animated a body of work that emerged alongside the nuclear age and matured as climate disruption moved from prediction to lived experience. Its premise was disarmingly simple: despair is not a failure of character, nor a symptom to be treated away, but evidence of care. If people could be helped to face grief for the world directly, the argument went, they might discover not paralysis but agency. The scholar who developed this approach drew from Buddhist thought, systems theory, and what came to be called deep ecology. She was less interested in prescribing solutions than in changing the conditions under which people perceived themselves and their place in the living world. Humans, she insisted, were not observers standing outside ecological collapse, but participants within a larger body that could be injured and renewed. Only after those ideas had begun to circulate widely did their author become a recognized figure. Joanna Macy, who died in July at 96, spent decades teaching that emotional honesty was a prerequisite for environmental action. She rejected the language of motivation and instead spoke of belonging. What people needed, she believed, was permission to feel what they already felt, in the…This article was originally published on Mongabay

From Conservation news via this RSS feed