Photographs by Dina Litovsky

The purge began late Friday night, four days after Donald Trump returned to the White House. Seventeen inspectors general—internal watchdogs embedded throughout the federal government—received emails notifying them of their termination. Three weeks later came the Valentine’s Day Massacre: the ousting of tens of thousands of federal employees with little discernible pattern, across agencies and across the country. By April, entire departments—the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—had been gutted.

Workers the administration couldn’t fire were coerced into leaving on their own. Toxicity became HR policy. Employees received an email with the subject line “Fork in the Road.” It offered eight months’ pay to anyone who resigned, and no assurances of job security to those who stayed. A follow-up email encouraged them “to move from lower productivity jobs in the public sector to higher productivity jobs in the private sector.” At the end of Trump’s first year back in office, roughly 300,000 fewer Americans worked for the government.

That number understates the destruction. When Trump anointed Elon Musk to lead the newly created Department of Government Efficiency, he did so in the name of clearing out mediocrities and laggards. The bureaucracy does harbor pockets of waste and paper-pushing positions that could easily be culled. But the administration showed little interest in understanding the organizations it was eviscerating. Any sincere attempt to reform the government would have protected its top experts and most skilled practitioners. In fact, such workers account for a disproportionate share of the Trump-era exodus. Many of them accepted the resignation package because they possessed marketable skills that allowed them to confidently walk away. The civil service thus lost the cohort that understands government best: the keepers of its unwritten manual, the custodians of institutional integrity.

Grover Norquist, one of the chief ideologists of modern conservatism, used to fantasize about drowning the government in the bathtub. The Trump administration has realized that macabre dream—not merely by shrinking the state, but by poisoning its culture. It has undone the bargain that once made government careers attractive: lower pay offset by uncommon job security and a sense of professional mission.

The American government grew in bursts of reform, crisis, and optimism—not from the sketching table of an engineer but from the rough contingencies of history. The outraged response to a 1969 oil fire on the Cuyahoga River catalyzed the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. The failure to prevent the September 11 attacks gave rise to the Department of Homeland Security. This accidental architecture was part of the federal government’s genius. It nurtured corners of national life—declining industries, obscure sciences—that a management consultant obsessed with optimization could never properly value. It embodied the wisdom, as well as some of the imperfections, of American history. For all its flaws, the American state was a source of national greatness and power: It ushered in an age of prosperity and discovery; it made everyday existence safer and fairer. It deserves, at the very least, the dignity of a proper burial.

In the late 19th century, as the American government took on its modern form, a single word captured the spirit of the enterprise: disinterestedness. The duties of civil servants, who remained in their chairs as presidents came and went, were supposed to transcend patronage and partisanship. Their professional obligation was to present facts and judgments that reflected an objective reality—not to flatter the preferences of the administration in power.

The nascent American state aspired to become a branch of science. It measured; it mapped; it studied. After its founding, in 1879, the United States Geological Survey recruited scientists and experts from Johns Hopkins, Yale, and Harvard. Using the most advanced techniques, it tracked river flow to forecast floods and to irrigate the arid West. It charted mineral belts in the Appalachians and the Rockies, which supplied the raw materials for industrial growth.

In the earliest decades of the 20th century, the National Bureau of Standards established common definitions for such basic measurements as the volt and the ohm, making it possible to build and trade at scale. The Bureau of Labor Statistics compiled data on wages, prices, and productivity that became the basis for economic prediction. The U.S. Weather Bureau allowed farmers to foresee storms.

The spirit of disinterestedness became the foundation for a regulatory state. Armed with scientific studies, the government could intervene to prevent disasters, protect consumers, and guard against recessions. Out of that faith in expertise arose the Federal Reserve and the Food and Drug Administration. Granite and marble buildings proliferated across Washington, D.C., housing a growing constellation of university-trained specialists. In their research and reports, they described what became the shared American reality.

The flaws in this system were obvious enough, at least in retrospect. Data points might be objective, but the decisions drawn from them were not. Handing power to experts—on the assumption that they alone were qualified to exercise it—sometimes bred insular arrogance. When the Army Corps of Engineers built levees on the lower Mississippi, it inadvertently magnified the devastation of the floods it had intended to prevent. Federal policies encouraging farmers to plow the prairie led to the ecological catastrophe known as the Dust Bowl. Those tendencies, many decades later, fueled the rise of Ronald Reagan, who famously said, “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: ‘I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.’ ”

Yet regulators also prevented immense human suffering. Before the advent of the modern state, the economy convulsed with financial panics roughly every 20 years. After the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation were created in the 1930s, confidence replaced chaos. Generations passed without bank runs. American markets became the safest bet on the planet.

At the dawn of the 20th century, American medicines were often laced with alcohol, opiates, or narcotics. Thanks to the FDA, those potions were gradually replaced by pharmaceuticals tested for safety—snake oil gave way to science.

The postwar era brought more triumphs. Following the arrival of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration in 1970, which mandated crash tests and new safety features, fatality rates from car accidents were cut by more than 70 percent. After the creation of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in 1971, workplace fatalities fell by nearly 70 percent. The state smoothed the roughest edges of the market; it tamed intractable dangers; it made American life more livable.

In the vernacular, the federal government is synonymous with Washington. That conflation obscures the fact that roughly 80 percent of its workforce is stationed outside the District of Columbia. Still, there’s no denying that Washington contains the densest concentration of civil servants—and the story of that caste is a morality tale.

In the 1970s, Washington was a city distinctly devoid of flash. Even its most powerful denizens drove beat-up Volvos; its dandies shopped at Brooks Brothers. The elegant houses of Georgetown were ostentatiously weather-beaten. The children of wealthy law-firm partners and humble bureaucrats attended the same schools.

But beginning in the late 20th century, lobbying became a boom industry. Those law partners, who sold their ability to influence policy, began raking in seven-figure salaries. A gap in wealth—and lifestyle—started to separate the lawyers in private practice from the civil servants. They lived in different neighborhoods, shopped at different stores, sent their kids to different schools.

That high-end lifestyle was seductive, and it attracted many government workers who wanted a beach house of their own. But the surprising thing, really, was how many preeminent experts—scientists, intelligence analysts, economists, even lawyers—stayed in their government job for the entire arc of their career.

They stayed because the work allowed them to accumulate new skills, to test themselves in crises, to solve novel problems. At its best, government work supplied the rush of being in the arena, a sense of professional purpose—a higher meaning than most jobs can muster.

Until the purges of the past year, the U.S. government housed an unmatched collection of experts, capable of some of the greatest feats in human existence. The achievements of this corps bear legendary names: the Manhattan Project, Apollo, the Human Genome Project. These aren’t just gauzy tales from the past. After the National Institutes of Health helped sequence the genome, it funded research that turned that knowledge into pioneering medicines with the potential to treat hundreds of rare diseases. It kept refining technology to make those treatments more affordable—and those therapeutics have dramatically improved survival rates for illnesses, such as pediatric leukemia and spinal muscular atrophy.

Under Trump, the expertise capable of such achievements has begun to vanish. His administration isn’t simply committed to shrinking government; it sees career officials as the enemy within, an entrenched elite exploiting its power and imposing its ideology on the nation. Its demise is not collateral damage but the imperative. What took generations to build is being dismantled in months, and with it goes not just expertise but what remains of the shared American faith in expertise itself.

Bureaucrats extol their ethos of service. They describe government work as a calling. Thirty percent of federal workers are military veterans who sought to extend their patriotic devotion into civilian life. Even those who never passed through the armed forces cast their career choices in similar terms. A generation of bureaucrats, now in the prime of their career, entered government after September 11. They were moved to emulate the commitment of the first responders they saw on television. They felt an obligation to serve.

Donald Trump has betrayed those workers. By describing them as a hostile force, he’s questioned their patriotism—and robbed the sense of mission from their work. Employees who signed up to serve a transcendent national interest, who understood their duty as being to the American people, now find themselves instructed to follow the whims of a corrupt, narcissistic leader.

What’s been lost isn’t just a sense of purpose, but a body of knowledge—a way of making the machinery of the state function. Early-20th-century bureaucrats may have aspired to govern as if they were practicing science, but the reality is something more like craft. The American state, a product of compromises, is tricky terrain to master. Organizations duplicate one another; agencies are overseen by political leaders who arrive with minimal understanding of the workplace they will manage. Succeeding in such an environment requires savvy veterans who have learned how to operate such an unruly machine and can model how to do so for fresh-faced co-workers. By wiping out many of the bureaucracy’s most experienced practitioners, Trump has severed the chain that allowed one generation of civil servants to pass on the habits of effective government to the next.

Some of Trump’s firings have drawn attention, such as the peremptory dismissal of C. Q. Brown, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, one of hundreds of military officers who have been removed alongside civil servants. But for the most part, the crumbling of the American state has unfolded as a quiet catastrophe. Bureaucrats are the definition of anonymous. Their prestige suffers because it is conflated in the public’s mind with long lines at the DMV, fastidious building inspectors, parking tickets—the stuff of local functionaries. So much of the civil service is devoted to long-term national flourishing—preventing disease, safeguarding financial markets—that its achievements go unappreciated.

The toll of the purge will become clear only gradually. When the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service loses the biologists who track bat populations, vulnerable species can no longer be rigorously protected. When bat populations dwindle, insects proliferate. Farmers will likely compensate by deploying insecticides, which government studies suggest can do significant prenatal harm. Government, too, is part of a delicate American ecosystem—as it erodes, crises that lay bare its indispensability will multiply.

Capturing the magnitude of the destruction is an almost impossible task. Statistics can convey the scale, but only individual stories reveal what has actually vanished, the knowledge and skill that have been recklessly discarded. The damage will ripple through every national park, every veterans’ hospital, every city and town.

Over the course of four months, I interviewed 50 federal workers, both civilian and military, who were either fired or forced out—who took early retirement or resigned rather than accept what their job had become. I wanted to understand how their time in government came to such an abrupt end and, more than that, to understand the career that preceded their departure. When The Atlantic asked their former agencies to comment, many declined, citing the privacy of personnel matters. In the name of protecting these workers, the government refused to defend the decisions that had upended their lives. What follows is their story—a portrait of the void that will haunt American life, a memorial to what the nation has lost.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Micaela White

Senior Humanitarian Adviser

United States Agency for International Development 2009–2025

By the beginning of 2025, there was a famine in Sudan, which meant that it was only a matter of time before the U.S. government dispatched Micaela White to the scene. She was America’s fixer of choice. Over her 16 years working for USAID, she was sent to manage the humanitarian response to catastrophes in Libya, Syria, Ukraine, and Gaza. Through street savvy and force of will, she could make the awful a little less so.

When White was brought into a crisis, she was usually granted official power to lead what is called a DART: a Disaster Assistance Response Team. Her improvisational skills were legendary. As a 29-year-old, she arrived in Haiti after the devastating earthquake of 2010 and took over an airfield in Port-au-Prince. Using a card table, she ran air-traffic control, prioritizing the arrival of search-and-rescue teams and turning away cargo planes carrying aid, which the broken nation wasn’t ready to accommodate. She said she worked until her feet were so swollen and bloody that she couldn’t remove her boots; she slept in a baggage cart; she lost 15 pounds. She imposed order on a chaotic situation so that humans could be quickly extracted from the rubble.

In 2011, White traveled to Benghazi with the envoy J. Christopher Stevens, who was later murdered in a terrorist attack. On that mission, she survived a car bombing of her hotel. She also managed to hire boat captains willing to transport food into the starving eastern half of Libya. Her persistence occasionally irked her superiors back home, like the time she assumed control of the Syrian DART without telling them that she was pregnant.

Averting mass starvation in Sudan didn’t require White to secure scarce resources. She said that when she arrived in Nairobi, Kenya, to oversee the effort, the United States had already purchased more than 100,000 tons of wheat and food products. But American officials struggled to deliver that aid to Sudan. White’s job was to find a pathway to get the supplies into the country. It soon became clear, however, that her most pressing challenge wasn’t the regime in Khartoum, but the administration in Washington. Trump had signed an executive order freezing USAID’s programs, a prelude to the agency’s dismantlement.

Over the next months, White watched as efforts to combat famine stalled. The administration barred her from communicating with the aid workers the U.S. had contracted with to operate inside Sudan. White was left with a handful of local staff, but then the administration stopped paying for their housing. White let some of them sleep in her hotel room—she amassed a $15,000 bill, which she paid with her personal credit card. (The government eventually reimbursed her.) DOGE cut off access to her email and her computer, but for some reason she could keep working on her iPhone.

American officials had managed to transport a stockpile of seeds to the country. But because the Trump administration had halted USAID programs, the agency could no longer fund the distribution of the seeds. White frantically tried to persuade European donors to take them before the stockpile spoiled. Eventually, Washington ordered her to return home. Thirty hours after landing in the U.S., she was fired.

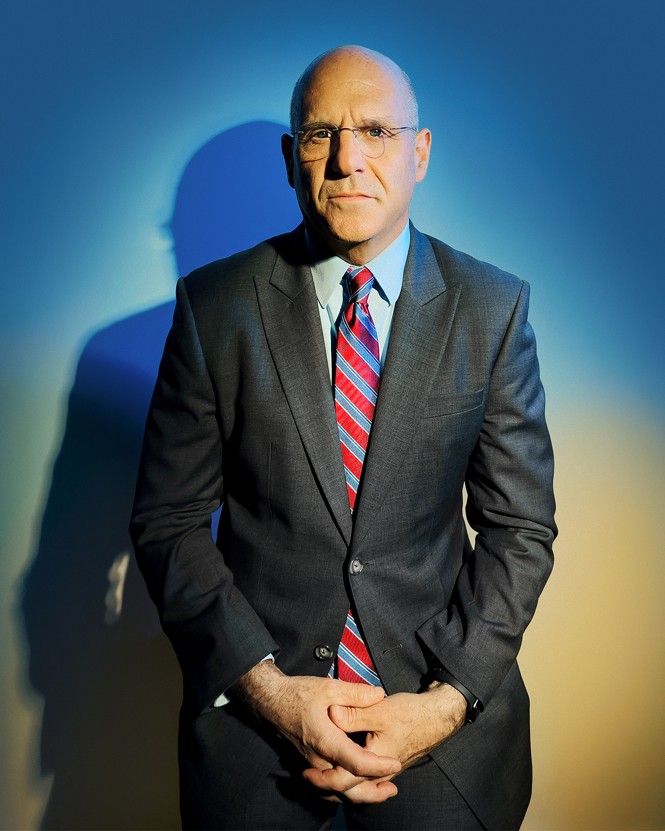

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Eric Green

Director, National Human Genome Research Institute

National Institutes of Health 1996–2025

In the years since landing a man on the moon, the greatest technological achievement of the American state has been the Human Genome Project—the mapping of the 3 billion building blocks of DNA. The project was international, but its central node was at the NIH. Eric Green, a physician and a scientist, was involved in the project from the start, and after it concluded, he became the head of the American genomics effort. Green’s accomplishment was to help make sequencing technology—once an enterprise that cost hundreds of millions of dollars—cheap enough for the average patient, enabling diagnoses of rare diseases. Under his leadership, the National Human Genome Research Institute advanced a revolution in medicine and a new understanding of cancer, because genomics could be used to analyze a tumor and suggest a treatment that might curtail its growth. On March 17, the Trump administration forced Green from his job, the first of five NIH-institute directors it removed. A Health and Human Services official told The Atlantic that “under a new administration, we have the right to remove individuals who do not align with the agency’s priorities.”

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Corina Allen

Tsunami-Program Manager

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 2024–2025

The nation’s tsunami-warning-system technology, much of which was created in the 1960s, was overdue for modernization. Corina Allen was overseeing its upgrade, which would have expanded its reach to newly discovered fault lines and improved its ability to anticipate flooding. She was fired on February 27, 2025.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Demetre Daskalakis

Director, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020–2025

A New York City physician and health official who got his start during the AIDS epidemic, Demetre Daskalakis communicated risk and allocated scarce resources—experience that enabled him to coordinate the national response to mpox. He resigned in August.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Wren Elhai

Foreign Service Officer

Department of State 2011–2025

To connect with citizens in his diplomatic posts, Wren Elhai joined a Russian bluegrass band, played fiddle in a Pakistani rock group, and entered a Central Asian–folk-music competition. After taking leave to study tech policy at Stanford, he helped build the State Department’s new cyberspace and digital-policy bureau. He was preparing to deploy to Senegal when he was fired, along with more than 200 other Foreign Service officers on domestic assignment. Because of ongoing litigation, these firings have been temporarily blocked, and Elhai and other officers are on administrative leave.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Brian Himmelsteib

Senior Foreign Service Officer

Department of State 2004–2025

On track to become an ambassador, Brian Himmelsteib served in Singapore and Laos while raising a son who uses a wheelchair. He returned to Washington in May so his son could undergo kidney surgery. Like Wren Elhai and other Foreign Service officers on domestic assignment, he was fired. While on administrative leave, he decided to retire from the Foreign Service.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Jason Robertson

Regional Director of Recreation, Lands, Minerals, and Volunteers

U.S. Forest Service, Department of Agriculture 2013–2025

Jason Robertson oversaw ski resorts and oil-and-gas operations across the Rockies, ensuring that private interests used public lands responsibly. He took a voluntary-resignation package in April, part of an exodus of roughly 4,000 Forest Service employees.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Melissa Rivera Pabón

Social-Media Specialist

Consumer Product Safety Commission 2023–2025

When the Consumer Product Safety Commission recalled an unsafe product—a potentially dangerous crib, batteries that could catch fire—Melissa Rivera Pabón posted the alert in English and Spanish. After she was fired, the office was down to one social-media specialist, who didn’t speak Spanish. A single mother of three, Rivera Pabón has struggled to find a full-time job.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Nadia Ford

Presidential Management Fellow

2023–2025

Nadia Ford’s mother is a teacher, and her father works for Customs and Border Protection. She wanted her own career in service and applied twice to join the two-year Presidential Management Fellows program, which recruited recent graduates with advanced degrees and cultivated them for leadership. The fellowship placed her in a small office in Health and Human Services devoted to promoting “healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood.” She had never heard of the office before, but began to think of its work as her calling. The programs it funded seemed to address some of the core causes of social misery: One of them counseled fathers just released from prison; another taught anger management to young couples. Trump signed an executive order killing the Presidential Management Fellows program on February 19, 2025. Ford was fired several months later, along with hundreds of other aspiring civil servants.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Liz Oyer

Pardon Attorney

Department of Justice 2022–2025

The presidential pardon is the Constitution’s ultimate extension of grace. Liz Oyer believed it should not be reserved for cronies and donors. She visited prisons to explain how inmates could apply for clemency; at the Justice Department, her office then vetted the petitions. But the Trump administration had other designs. It asked her to assemble a list of convicts whose criminal history prevented them from owning firearms, so that the attorney general could restore that right. An associate deputy attorney general instructed her to add the actor Mel Gibson, who had a domestic-violence conviction, to the list. Because he hadn’t undergone a background check, as everyone else she’d recommended had, Oyer balked. Her hesitance marked her as disloyal, and she was fired on March 7. (When asked for comment by The Atlantic, a DOJ official pointed to Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche’s comments from several months earlier, in which he disputed Oyer’s version of events and called her allegations “a shameful distraction from our critical mission to prosecute violent crime, enforce our nation’s immigration laws, and make America safe again.”)

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Jeff Cohen

Mission Director, Indonesia

United States Agency for International Development 2005–2025

There is no manual for soft-power diplomacy. Jeff Cohen’s education began when he was a Peace Corps volunteer in Bolivia. With USAID, he served in the Dominican Republic, Peru, and Afghanistan. He became adept at improvising programs that burnished America’s prestige. During Cohen’s last assignment, in Indonesia, where he oversaw a staff of 150, he persuaded a mining company and a church charity to help launch an initiative to fight childhood malnutrition. He ran projects to save forests and to stop tuberculosis. This wasn’t just a display of American beneficence: Cohen was acutely aware that he was competing with Chinese diplomats in a global battle for hearts and minds. On March 28, the Trump administration dismantled USAID, erasing more than 60 years of development expertise.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Bree Fram

Colonel

Space Force 2021–2025

As a kid, Bree Fram dreamed of becoming an astronaut. After 9/11, she joined the Air Force and deployed to the Persian Gulf, where she tested new technologies to protect convoys from improvised explosive devices. That assignment led to her specialty: managing teams that built novel systems. (One came up with tools that could be used to take over an attacking drone, forcing it to fall from the sky.) The military kept sending Fram back to school, and her advanced degrees piled up. When the Space Force was created, she drafted its blueprint for acquiring the technologies of the future and ensured that new initiatives didn’t get smothered by bureaucracy. Her mission was cut short by a biographical fact: Fram is transgender. Upon arriving in office, Trump barred from service anyone who did not identify with their birth gender.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Paula Soldner

Food Inspector

Food Safety and Inspection Service, Department of Agriculture 1987–2025

Just before Paula Soldner graduated from the University of Iowa, her mother handed her an application for federal employment. Two weeks later, she was inspecting a plant where eggs were processed for industrial bakeries and military bases. Eventually, she began working in slaughterhouses and factories that turned out sausage, bratwurst, and pork hocks, scanning for unhygienic practices that might spread disease to the nation’s kitchens. Soldner grew accustomed to the sight of blood—and to retreating to the locker room to wash animal innards off her uniform. A fierce advocate for her union, she was elected chair of the National Joint Council of Food Inspection Locals. In April, she accepted the Trump administration’s offer of early retirement—as did many of her colleagues. According to the government’s own data, as of March, the Food Safety and Inspection Service had lost about 8 percent of its workforce.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Peter Marks

Director, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research

Food and Drug Administration 2012–2025

Peter Marks was a driving force behind Operation Warp Speed—a name he coined—leading the FDA’s review of COVID‑19 vaccines at an unprecedented pace. Before entering government, he had been a clinical director at Yale’s Smilow Cancer Hospital. At the FDA, he surmounted regulatory roadblocks to advance gene and cell therapies, and helped create the Rare Disease Innovation Hub to spur treatments for often-overlooked conditions. When Robert F. Kennedy Jr. took over Health and Human Services, his office asked Marks for access to a database tracking vaccine safety; he agreed. But Marks refused to give Kennedy’s team the ability to edit the data, which made his ouster inevitable. An HHS official told The Atlantic that Marks “did not want to get behind restoring science to its golden standard” and that he therefore “had no place at FDA.”

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Elijah Jackson

Information-Technology Specialist

Food and Drug Administration 2012–2025

In the Navy, while serving in the Persian Gulf, Elijah Jackson lost one hand and part of a finger on the other. Doctors diagnosed him with PTSD. But he came from a military family in southern Georgia, and he still felt the tug of duty. Eventually, Jackson landed at the FDA, where he worked in an office managing IT contracts, procuring the data tools that scientists used to evaluate drug safety. By closely monitoring contractors’ sloppy billing habits, he said, his office saved nearly $18 million in a year and a half. On April 1, that office was eliminated. According to Jackson, more than 50 employees, who managed $5 billion in contracts, were reduced to two part-timers. A Health and Human Services official said in a statement to The Atlantic that “under Secretary Kennedy’s leadership, the Department has taken significant steps to streamline operations” at the agency.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Crystal Huff

Prosthetic Clerk

Department of Veterans Affairs 2024–2025

When Crystal Huff, a Navy vet, went to pick up a back brace at a VA clinic in Fort Worth, Texas, in 2023, a woman at the front desk treated her with rude indifference. Offended, Huff lodged a complaint with the patient advocate’s office. A few weeks later, a supervisor at the clinic called to discuss the incident. Despite the circumstances of the call, he found Huff to be warm and loquacious. “I need someone like you, with your personality,” he told her, urging her to apply to fill a vacancy.

A year after that, Huff began as a clerk in the clinic’s prosthetics department, a misleading name: The department supplied wheelchair ramps, nebulizers, and ice packs as well as artificial limbs. She issued the equipment and arranged for it to be installed.

Huff, a Christian, aspired to a life of service. When she arrived at work, a gaggle of vets usually awaited her. During her time in the prosthetics department, she never met an ill-tempered one. In fact, she sometimes found candy and other small tokens of gratitude on her chair.

None of that goodwill, however, insulated her from DOGE. Because she had been on the job less than two years, she was fired last February, along with other federal employees classified as “probationary.” According to Huff, when she received her next paycheck, it was for $1.68, an apparent accounting error. Not long after, a judge stepped in to rescue her job, quickly ruling that the administration didn’t have the authority to fire probationary workers en masse. In March, Huff returned to the clinic.

On April 4, the VA offered employees the chance to voluntarily resign, which would allow them to be paid their full wages until September 30. Because she no longer considered the government a reliable employer, Huff accepted. In June, she left the VA, as did three other workers in her 12-person department.

But she said that when she checked her bank account, she found that the government had severely underpaid her again. After a week of frantic phone calls, Huff heard from a woman in HR, who informed her that her file indicated that she had been “terminated.” What does that mean? Huff asked. Despite having accepted the voluntary-resignation offer, Huff had been fired, and nobody had bothered to tell her or explain why. The severance she’d been promised would never arrive, and Huff was barred from federal employment for the next three years.

To pay the bills, she began delivering groceries, but the work was not enough to prevent her from falling three months behind on her mortgage.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Merici Vinton

Senior Adviser

Internal Revenue Service 2023–2025

No agency embodies government dysfunction like the IRS, where employees still type in data from paper tax returns. Merici Vinton, orphaned at 11, grew up on a remote ranch in Nebraska. After working on Barack Obama’s first presidential campaign, she met reformers passionate about using technology to improve government. She was a lead architect of Direct File, a free website that allowed Americans to file taxes—or claim refunds—without hiring an accountant or buying software. She was initially hopeful about the arrival of DOGE, thinking it might hasten the pace of IRS reforms. But when it became clear that Direct File was going to be scrapped and her colleagues working on modernization were dismissed, she resigned on March 11.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Mamta Patel Nagaraja

Associate Chief Scientist for Exploration and Applied Research

NASA 2001–2025

Mamta Patel Nagaraja’s parents, immigrants from Gujarat, India, owned a motel on the edge of a small Texas town. As a girl, she would help her father with repairs, foreshadowing a career in engineering. An internship set Nagaraja on a dream path at Johnson Space Center. She trained astronauts. She wore a headset in Mission Control. She helped design a rescue vehicle for the International Space Station. After returning to school for a Ph.D. in bioengineering, Nagaraja eventually moved to NASA headquarters. As an associate chief scientist, she helped guide experiments that exploited the manufacturing possibilities of space, where weightlessness allows for the precise fabrication of pure metals and silicon. She worked with a team that was building an artificial retina, on the cusp of entering clinical trials, and another that was creating carbon fiber in its strongest form. The Trump administration eliminated the Office of the Chief Scientist on April 10.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Mark Gross

Chief, International Migration Branch

Census Bureau 2019–2025

A demographer by training, Mark Gross was charged with estimating the number of people leaving and entering the country each year—the data he and his team produced tracked international migration down to the county level. Their numbers partly determined how federal funds were distributed. He resigned in the fall.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Ryan Hippenstiel

Field Operations Branch Chief

National Geodetic Survey 2016–2025

The Earth is never still—its axis wobbles; storms redraw shorelines—which throws maps and GPS data out of sync. Ryan Hippenstiel sent surveyors into the field to measure those subtle changes, preventing ships from running aground and keeping navigation systems accurate. He accepted a voluntary-resignation package in April.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

David Pekoske

Administrator, Transportation Security Administration

Department of Homeland Security 2017–2025

A three-star Coast Guard admiral, David Pekoske brought stability to an agency plagued by leadership turnover and boosted pay for TSA employees, which lifted the agency’s sagging morale and stemmed the attrition of airport screening officers. The Trump administration fired him on Inauguration Day.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Tom Di Liberto

Public-Affairs Specialist/Climate Scientist

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 2023–2025

When models predicted El Niño or La Niña climate events, Tom Di Liberto sounded the alarm. He briefed city planners, private utilities, and officials from the National Security Council so they could prepare for the coming deluge or drought. When the Trump administration fired him, he was two weeks short of the seniority that would have saved his job.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Rebecca Slaughter

Commissioner

Federal Trade Commission 2018–2025

Rebecca Slaughter pushed the FTC to crack down on companies that exploited personal data without meaningful consent. In his bid to rob agencies of their independence, Trump took the unprecedented step of firing Slaughter in March, along with the other Senate-confirmed Democratic member of the bipartisan FTC. (Slaughter has sued, and her case is pending before the Supreme Court.)

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Ashley Sheriff

Chief Strategy Officer, Office of Public and Indian Housing

Department of Housing and Urban Development 2020–2025

Ashley Sheriff led a team that rewrote the decades-old safety code for public housing so that it limited toxic mold and reduced the risk of catastrophic fires. She resigned in March.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Paul Osadebe

Attorney

Office of Fair Housing, Department of Housing and Urban Development 2021–2025

Paul Osadebe immigrated to Texas from Nigeria at the age of 4. His life’s goal was to become a civil-rights attorney. At HUD, he wrote regulations that made it easier to bring housing-discrimination suits; he prosecuted cases using new authority granted by Congress to protect victims of domestic abuse living in federally funded housing. When the Trump administration froze hundreds of fair-housing cases and reassigned lawyers in his office to other divisions, Osadebe and three of his colleagues submitted a whistleblower’s complaint to Senator Elizabeth Warren. He also gave an interview to The New York Times describing how the department was shirking its legal obligation to protect civil rights and filed a lawsuit demanding that the department reinstate him to his old job. On September 29, he was told that he was being placed on administrative leave because he had disclosed “nonpublic information for private gain.” The outcome of his case is unresolved. Osadebe spoke with The Atlantic in his personal capacity, not as a representative of the government.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Karen Matragrano

Deputy Chief Information Officer

Department of the Interior 2005–2025

Karen Matragrano oversaw the Interior Department’s $2 billion portfolio of information technology, including systems tracking oil-and-gas revenue that Interior collects. When DOGE began operating in her department, it wanted unfettered access to the payroll system—which would have allowed it to circumvent HR procedures and privacy protections. Rather than comply with DOGE’s demand, Matragrano resigned. Her dissent proved futile: After her departure, DOGE gained access to the system.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Ruslan Petrychka

Chief of the Ukrainian Service

Voice Of America 2007–2025

Ukrainian broadcast news has never had a reputation for ethical rigor. Oligarch-owned networks tailored their reporting to serve their benefactors’ interests. Ruslan Petrychka, a veteran of Kyiv media who immigrated to Washington, D.C., made it his mission to model objectivity in the reports he produced in his native language for Voice of America. After Russia’s invasion in 2022, Petrychka’s service became indispensable. On highly watched Ukrainian-TV programs, his reporters would explain the American political system—without conspiracy, without exaggeration. On March 14, Trump ordered the dismantling of Voice of America’s parent agency.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

Michael Lauer

Deputy Director for Extramural Research

National Institutes of Health 2007–2025

In 2024, the NIH spent $38 billion sustaining research across universities and hospitals. Michael Lauer oversaw that money with a relentless commitment to transparency: Grantees who once buried results had to post them within a year of completion. Lauer also set up systems to probe sexual-harassment complaints in research labs, and to flag undisclosed foreign ties. He retired after Health and Human Services officials attempted to demote his boss and the Trump administration tried to freeze grants he oversaw.

Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

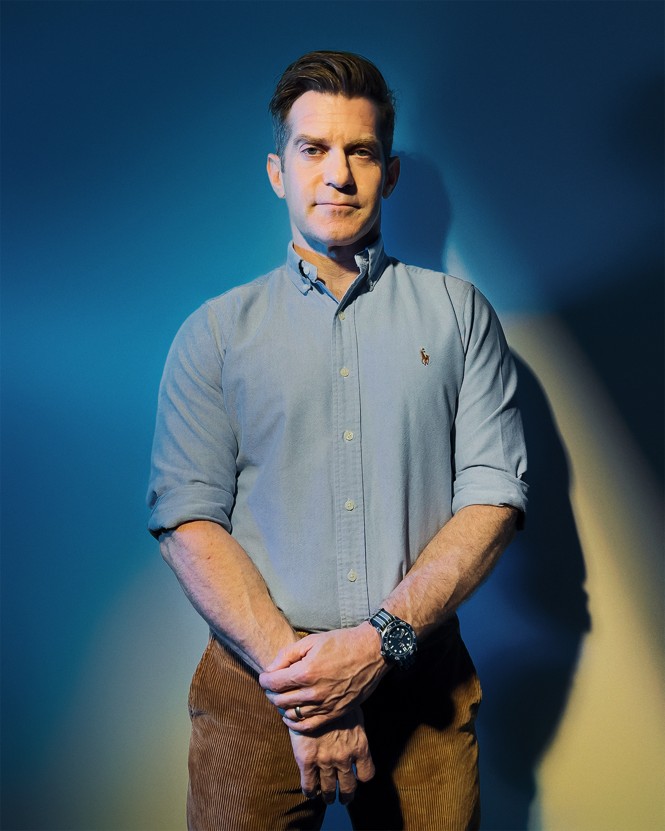

Michael Feinberg

Assistant Special Agent in Charge

Federal Bureau of Investigation 2009–2025

[Content truncated due to length…]

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed