The line between a Linux user and a Linux power user is a bit gray, and a bit wide. Most people who install Linux already have more computer literacy than average, and the platform has long encouraged experimentation and construction in a way macOS and Windows generally aren’t designed for. Traditional Linux distributions often ask more of their users as well, requiring at least a passing familiarity with the terminal and the operating system’s internals especially once something inevitably breaks.

In recent years, however, a different design philosophy has been gaining ground. Immutable Linux distributions like Fedora Silverblue, openSUSE MicroOS, and NixOS dramatically reduce the chances an installation behaves erratically by making direct changes to the underlying system either impossible or irrelevant.

SteamOS fits squarely into this category as well. While it’s best known for its console-like gaming mode it also includes a fully featured Linux desktop, which is a major part of its appeal and the reason I bought a Steam Deck in the first place. For someone coming from Windows or macOS, this desktop provides a familiar, fully functional environment: web browsing, media playback, and other basic tools all work out of the box.

As a Linux power user encountering an immutable desktop for the first time, though, that desktop mode wasn’t quite what I expected. It handles these everyday tasks exceptionally well, but performing the home sysadmin chores that are second nature to me on a Debian system takes a very different mindset and a bit of effort.

Deck Does What Others Don’t

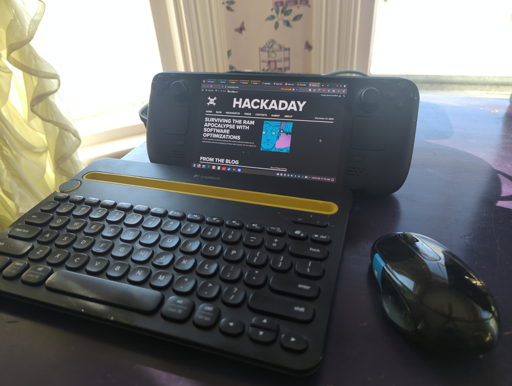

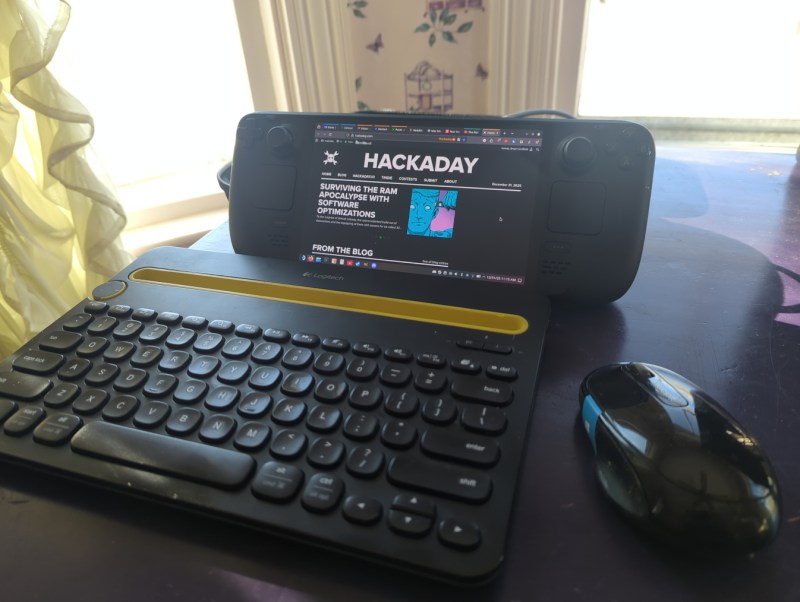

I’ve owned my Deck for about a year now. Beyond gaming, the desktop mode has proven its value: it uses what essentially amounts to laptop hardware in a much smaller form factor, and is arguably more portable as a result. It easily plugs in to my existing workstation docks, so it’s easy to tote around, plug in, and start using. With a Bluetooth keyboard and mouse along with something to prop it up on, it makes an acceptable laptop substitute in certain situations as well. It’s also much more powerful than most of my other laptops with the possible exception of my M1 Macbook Air.

However, none of the reviews I watched or read circa 2023-2024 fully explained what an immutable OS was and how it’s different than something like Ubuntu or Fedora. Most of what I heard was that it runs “a modified version of Arch” with a “full Linux desktop” and little detail other than that, presumably to appeal to a wider audience that would be used to a fairly standard Windows PC otherwise. As a long-time Linux user the reviews I read led me to believe I’d probably just boot it up, open a terminal, and run pacman -S for all of the tools and software I’d normally install on any of my Debian machines.

Anyone familiar with immutable operating systems at this point will likely be laughing at my hubris and folly, although it’s not the first time I jumped into a project without a full understanding of what I would be doing. Again, having essentially no experience with immutable operating systems beyond having seen these words written together on a page, I was baffled at what was happening once I got my hands on my Deck and booted it into the desktop mode. I couldn’t install anything the way I was used to, and it took an embarrassing amount of time before I realized even basic things like Firefox and LibreOffice had to be installed with Flatpaks. These are self-contained Linux applications that bundle most of their own dependencies and run inside a sandbox, rather than relying on the host system’s libraries. In SteamOS they are installed in the home directory, which is important because any system updates from Valve will rewrite the entire installation except the home directory. They’re also installed from an app store of sorts, which also took some getting used to as I’ve been spoiled by about 20 years of apt having everything I could ever need.

My main workstation. With a USB-C dock I can use any modern computer here, including the Steam Deck

But after that major hiccup of learning what my operating system was actually doing, it was fairly easy to get it working well enough to browse the internet, write Hackaday articles, and do anything else I could do with any other average laptop. This is the design intent of the Steam Deck, after all. It’s not meant for Linux power users, it’s meant as a computer where the operating system gets out of the way and lets its user play games or easily work in a recognizable desktop environment without needing extensive background Linux knowledge. That doesn’t mean that power users can’t get in and tinker, though; in fact tinkering is almost encouraged on this device. It just means that if they’re used to Debian, like I am, they have to learn a completely new way of working than they’re used to.

Going Beyond Intended Use

To start, I use a few tools on my home network that make it easier for me to move from computer to computer without interrupting any of my workflows. The first is Syncthing, which is essentially a self-hosted and decentralized Dropbox replacement that lets me sync files and folders automatically across various computers. Installing Syncthing is straightforward with a Flatpak but getting things to run at boot is not as easy. I did eventually get it working seamlessly by following this guide, though. This was my first learning experience on how to start system processes outside of a simple systemd command. Syncthing is a non-negotiable for me at this point as well and is essentially load-bearing in my workflow, and is actually the main reason I switched my Gentoo install from openRC to systemd since openRC couldn’t easily run a task at boot time as a non-root user.

I’m also a fan of NFS for network file sharing (as the name implies) and avoid Samba to stay away from any potential Windows baggage, although it’s generally a more supported file sharing protocol. Nonetheless, my media libraries all stream over my LAN using NFS, and my TrueNAS virtual machine on my Proxmox server also uses this protocol, so it was essential to get this working on my Deck as well.

Arguably Samba would be easier but we are nothing without our principles, however frivolous. On a Debian machine I would just edit /etc/fstab with the NFS share and mount points and be done, but consistently mounting my network shares at boot in SteamOS has been a bit elusive. Part of the problem is how SteamOS abstracts away root access in ways that are different from a traditional Linux installation, so things that need to be done at boot by root are not as easy to figure out. I have a workaround where I run a script to mount them quickly when I need them and it’s been working well enough that I haven’t figured out a true solution to this problem yet, but generally SteamOS doesn’t seem to be designed for persistent system-level configuration like this.

The only other major piece of infrastructure I run on all of my machines is Tailscale, which lets me easily configure a VPN for all of my devices so I can access them from anywhere with a network connection, not just when directly connected to my LAN. This was one of the easier things to figure out, as the Tailscale devs maintain an install script which automates the process and keeps the user from needing to do anything overly dramatic. This Reddit post goes into some Steam Deck-specific details that are helpful as well.

Ups and Downs

There were a few minor niggles for me even after sorting these major issues out. The Deck is actually quite capable of running virtual machines with its relatively powerful hardware, but the only virtualization software I’ve found as a Flatpak is Boxes, which is a bit limiting for those used to something like VMWare Workstation or KVM. Still, it works well enough that I’ve been able to experiment running other Linux operating systems easily on the Deck, and even tried out an old Windows XP image I have which I keep mostly so I can play my original copy of Starcraft without having to fuss with Wine.

Other than that, the default username “deck” trips me up in the terminal because I often forget it’s not the same username that I use for the the other machines on my network. The KDE Plasma desktop is also running X11 by default, and since I’ve converted all of my other machines to Wayland in an attempt to modernize, the Deck’s desktop feels a bit dated to me in that respect. My only other gripe is cosmetic in nature: I do prefer GNOME, and although SteamOS uses KDE as its default desktop environment I don’t care so deeply that I’ve tried to make any dramatic changes.

Provided there’s something to prop the Deck against, it can make a good laptop replacement using a Bluetooth mouse and keyboard in certain situations as well.

There have been a number of surprising side effects of running a system like this as well. Notably, the combination of Tailscale and Syncthing running at boot, even in gaming mode, lets me sync save states from non-Steam games, including emulators, so I can have a seamless experience moving from gaming on my Steam Deck to gaming on my desktop. (I’m still running this hardware for my desktop with the IME disabled.)

I’d actually go as far as recommend this software combination to anyone gaming across multiple machines based on how well it works. Beyond that major upside, I’ll also point out that running Filezilla as a Flatpak that gets automatically updated makes it much less annoying about reminding the user that there’s an update available, which has always been a little irksome to me otherwise.

The Steam Deck as a platform has also gotten a few of my old friends back into gaming after years of life getting in the way of building new desktop computers. It’s a painless way of getting a capable gaming rig, with the Steam Machine set to improve Valve’s offerings in this arena as well. So being able to reconnect with some of my older friends over a game of Split Fiction or Deep Rock Galactic has been a pleasant perk as well, although the Deck’s cultural cachet in this regard is a bit outside of our scope here.

I’ll also point out that this isn’t the only way of using the Deck as a generic Linux PC, either. I’ve mostly been trying to stick within the intended use of SteamOS as immutable Linux installation, but it’s possible to ignore this guiderail somewhat. The read-only filesystem that’s core to the OS’s immutability can be made writable with a simple command, and from there it behaves essentially like any other Arch installation.

Programs can be installed via pacman and, once everything is configured to one’s liking, the read-only state can be re-enabled. The only downside of this method is that a system update from Valve will wipe all of these changes. System updates don’t happen incredibly often, though, and keeping track of installed packages in a script that can be run after any updates will quickly get the system back to its pre-update condition. Going even farther than that, though, it’s also possible to install any operating system to a microSD card and use the Deck as you might any other laptop or PC, but for me this misses the point of learning a new tool and experiencing a different environment for its own sake, and also seems like a bit of overkill when there’s already a fully functional Linux install built into the machine.

An Excellent New Tool

Although my first experience with an immutable Linux distribution was a bit rough around the edges, it felt a lot like the first time I tried Linux back in 2005, right down to not entirely understanding how software was supposed to be installed at first. I was working with something new without fully grasping what I’d signed up for, and moments like using a software repository for the first time were genuinely eye-opening. Back then, not having to hunt down sketchy .exe files on the Internet just to get basic functionality on my computer felt revelatory; today, immutable distributions offer a similar shift, trading some initial confusion on my part for a system that’s more reliable and far harder to break. Even after years of using mainstream Linux distributions, there’s still plenty to learn, and that process of figuring things out remains part of the fun.

There’s never been a better time to get into Linux, either. Hardware prices keep climbing as a result of the AI bubble, all while Microsoft continues to treat perfectly functional PCs as e-waste and tightens the screws on their spyware-based ecosystem that users have vanishingly little control over. Against that backdrop, immutable Linux distributions like SteamOS, Bazzite, Fedora Silverblue, or even the old standbys like Mint, Debian, and Arch offer a way to keep using capable hardware without spending any money.

Even for longtime Debian system administrators and power users, immutable distributions are a new tool genuinely worth learning, with the caveat that there will likely be lots of issues like mine that crop up but which aren’t insurmountable. These tools represent a different way of thinking about what an operating system should be, though, and it’s exciting to see what that shift could mean for the future of PCs and gaming outside the increasingly hostile Microsoft–Apple duopoly.

From Blog – Hackaday via this RSS feed