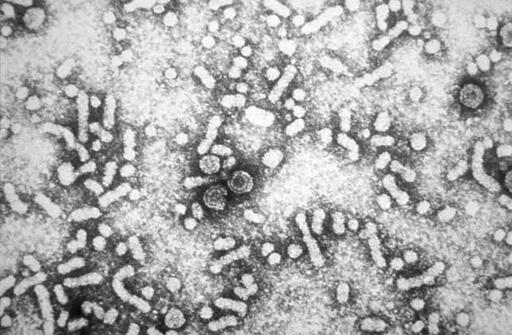

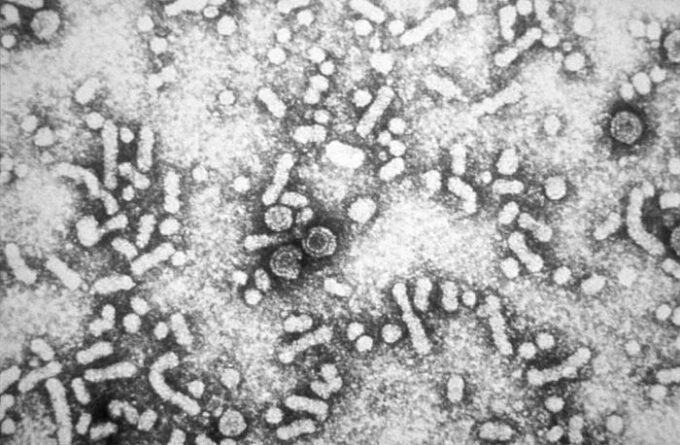

An electron micrograph showing the presence of hepatitis-B virus HBV “Dane particles”, or virions. Photo: CDC.

“If you’ve been hearing renewed debate about the hepatitis B vaccine for newborns, you’re not alone. A mix of policy proposals, selective research citations, and rhetoric about “choice” has brought a long-settled public-health intervention back into the spotlight. The result has been confusion for parents and clinicians alike. Here’s what actually matters.

First, the science on hepatitis B is not new or controversial

Hepatitis B is a viral infection that can become chronic and lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer later in life. When infection occurs at birth or in early infancy, the risk of chronic infection is especially high. That is why the hepatitis B vaccine is given at birth in many countries, including the United States.

This approach works. Since the introduction of universal newborn vaccination, rates of chronic hepatitis B infection in children have dropped dramatically. The birth dose protects infants not only from known maternal infection, but also from undiagnosed cases, testing errors, and postnatal exposure. It is a safety net built into the system.

So why is the birth dose being questioned now?

Much of the current debate traces back to a set of studies conducted in Guinea-Bissau that explored what researchers call “non-specific effects” of vaccines. These studies examined whether certain vaccines appeared to influence overall mortality beyond protection against the targeted disease.

Some findings suggested differences in outcomes based on vaccine type or timing in very specific settings. Those results generated scientific discussion, but they were never intended to drive vaccine policy in high-income countries.

That context matters.

Why the Guinea-Bissau findings do not translate to the U.S.

Guinea-Bissau is a low-income country with historically high child mortality, limited healthcare access, different disease exposure patterns, and inconsistent follow-up care. The studies in question were conducted in environments shaped by malnutrition, untreated infections, and fragile medical infrastructure. Those conditions fundamentally alter health outcomes and do not translate to countries like the United States.

I say this not abstractly, but from experience. I worked next door in Sierra Leone during the Ebola epidemic, in settings where the absence of infrastructure determined who lived and who died. When research conducted in such contexts is selectively used to justify weakening protections for children elsewhere, it crosses an ethical line. Major global health bodies, including the World Health Organization, have reviewed this research and concluded that it does not justify changes to routine childhood vaccination schedules in high-income countries. The findings are hypothesis-generating, not evidence of harm.

Using these studies to argue against the hepatitis B birth dose in the U.S. is not just a scientific stretch. It echoes a deeply troubling history in public health, where vulnerable populations are treated as means to an end rather than communities deserving protection. The comparison to Tuskegee is not made lightly. Research that shifts risk onto marginalized groups to advance ideological arguments elsewhere is ethically abhorrent, regardless of the language used to justify it.

What policy changes would actually mean

Moving the hepatitis B vaccine out of the routine newborn schedule would not just affect individual choice. It would affect access.

In the U.S., routine vaccine recommendations determine insurance coverage, eligibility for the Vaccines for Children program, and supply stability. Delaying or removing the birth dose would disproportionately affect infants born into unstable healthcare situations, including those without consistent prenatal care or insurance. It would also increase the risk of missed vaccinations later in infancy, when follow-up is less reliable.

What parents should take away

This is not a debate about whether hepatitis B vaccination works. It does. It is about whether we maintain systems that deliver protection consistently, especially to those most at risk.

The birth dose exists because real-world healthcare is imperfect. It is designed to protect infants even when screening fails, records are incomplete, or follow-up is delayed. Weakening that protection does not increase safety. It increases vulnerability.

Public health succeeds when it anticipates gaps and closes them before harm occurs. The hepatitis B birth dose is one of the clearest examples of that principle in action.”

The post The Science on the Hep B Vaccine for Newborns appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed