The Silver Casket and the Red Leather Box by William Nicholson

Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital!

This week in The Times I wrote about the twenty-first century decline in philanthropy and the age hyper-individualism. I’m increasingly persuaded the idea that the individualist chaos of modern societies may have at least something to do with the fading of Christian-derived moral ideas about charity, humility and turning the other cheek. Ideas now replaced by the omnipresent individualist clichés about the importance of “being yourself” and “following your dreams”.

The piece was strongly informed by Robert Wright’s brilliant book The Evolution of God which argues that Abrahamic religions with their strong emphasis on pro-social behaviours evolved in increasingly large and complex Iron Age societies that needed an ethic of of neighbourliness to guide the behaviour of citizens who were required to rub along with more and more different people and especially more and more strangers. In many ancient polytheistic religions the gods were not particularly concerned with human morality. Religion was more transactional — “I give you charred goat intestines, you give me a good harvest”.

Thanks for reading Cultural Capital! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The AI memorisation crisisThis is a great piece in The Atlantic explaining how Large Language Models work. The argument is that LLMs aren’t intelligent and that they don’t “learn”. Much of this is tech industry propaganda.

Another way of thinking about how LLMs operate is that they are just a way of storing copies of texts and images which they draw on as they regurgitate their outputs:

In fact, many AI developers use a more technically accurate term when talking about these models: lossy compression… The phrase was recently invoked by a court in Germany that ruled against OpenAI in a case brought by GEMA, a music-licensing organization. GEMA showed that ChatGPT could output close imitations of song lyrics. The judge compared the model to MP3 and JPEG files, which store your music and photos in files that are smaller than the raw, uncompressed originals. When you store a high-quality photo as a JPEG, for example, the result is a somewhat lower-quality photo, in some cases with blurring or visual artifacts added. A lossy-compression algorithm still stores the photo, but it’s an approximation rather than the exact file. It’s called lossy compression because some of the data are lost.

From a technical perspective, this compression process is much like what happens inside AI models, as researchers from several AI companies and universities have explained to me in the past few months. They ingest text and images, and output text and images that approximate those inputs.

The image on the left is the original. The image on the right is the poorer quality AI version. Sometimes LLMs do more than merely approximate the information they store:

Sometimes the language map is detailed enough that it contains exact copies of whole books and articles. This past summer, a study of several LLMs found that Meta’s Llama 3.1-70B model can, like Claude, effectively reproduce the full text of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. The researchers gave the model just the book’s first few tokens, “Mr. and Mrs. D.” In Llama’s internal language map, the text most likely to follow was: “ursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much.” This is precisely the book’s first sentence. Repeatedly feeding the model’s output back in, Llama continued in this vein until it produced the entire book, omitting just a few short sentences.

Martin Luther rewired your brainA friend sent me this great piece by the anthropologist Joseph Henrich on the relationship between Protestantism and literacy which is still observable in the world today. It’s nice to be reminded of Henrich’s ideas. The piece draws on the opening pages of his fantastic book The Weirdest People in the World which is one of the handful of books that has genuinely changed the way I see the world. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

This piece is a good introduction to a crucial part of Henrich’s argument is that cultural factors really can shape history. We now know that culturally-acquired skills “rewire” our brains which means that culture isn’t just something floating in the air, it materially changes human populations just like technology, economics and the climate.

As Henrich writes, one of the most dramatic ways we “rewire” our brains is by learning to read. Protestantism’s emphasis on literacy is one of the most important “cultural mutations” that helped to shape the world we know today:

In the wake of the spread of Protestantism, the literacy rates in the newly reforming populations in Britain, Sweden, and the Netherlands surged past more cosmopolitan places like Italy and France. Motivated by eternal salvation, parents and leaders made sure the children learned to read.

[…]

The Protestant impact on literacy and education can still be observed today in the differential impact of Protestant vs. Catholic missions in Africa and India. In Africa, regions with early Protestant missions at the beginning of the Twentieth Century (now long gone) are associated with literacy rates that are about 16 percentage points higher, on average, than those associated with Catholic missions. In some analyses, Catholics have no impact on literacy at all unless they faced direct competition for souls from Protestant missions. These impacts can also be found in early twentieth-century China.

Mysteries of international shippingThis wonderful interactive map shows tens of thousands of moving dots representing container ships streaming around the world over the course of a year. You can travel around and zoom in and out. It’s a useful reminder of how mindbogglingly complex the world economy. And how fragile it is. You can see little build-ups of bumping yellow dots all trying to squeeze through the Suez canal and the Panama Canal.

A Walk After DarkOne of the advantages of having a newsletter is that you can foist your obsessions on subscribers. My current obsession is this Auden poem, ‘A Walk After Dark’. It’s from later in his career (1948) so it’s less dazzling and spectacular than the early stuff.

I like this softer version of the Auden voice — charming, self-amused, whimsical, slightly melancholy, a bit more honest than his younger self.

In ‘A Walk After Dark’ the middle aged Auden is walking under the night sky thinking about ageing and time. He is comforted by the idea that the stars aren’t gears in the gleaming Newtonian machinery of a clockwork universe but elderly points of ancient light sent out long ago and only now reaching earth, making them, like him “creatures of middle age”. Everything grows old, even the stars. Auden could think about the sky like this:

It’s cosier thinking of nightAs more an Old People’s HomeThan a shed for a faultless machine,That the red pre-Cambrian lightIs gone like Imperial RomeOr myself at seventeen.

There’s a great recording of him reading it too. He had the best voice of any poet:

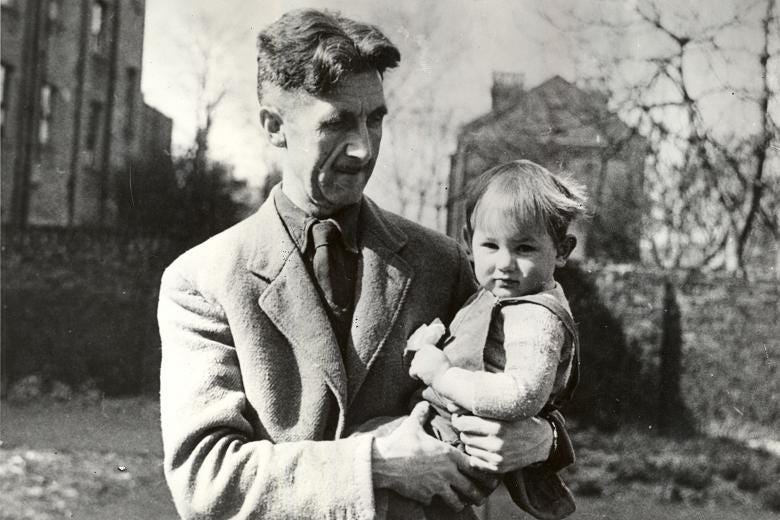

Some fragments of the genius of George OrwellFor a long time I foolishly scorned George Orwell. I think the prejudice is common among people of my generation (well among people of my generation who care about such things). Orwell is viewed as a fetish of boomer columnists — the types of people who sit in their houses in Hampstead being paid six figures by broadsheet newspapers not really trying with their prose and fondly imagining they are working in plain Orwellian sentences and fearlessly speaking truth to power.

Anyway, I’ve been slowly coming around from this obviously absurd and wrong opinion. Orwell is genius. I’m quite glad I’ve saved him up for myself. For Christmas my girlfriend got me the brilliant four volume edition of his essays, journalism and letters which was published by Penguin in the seventies. I found it pure pleasure to read and strongly recommend trying to get hold of a copy if you can. Here are a few bits I found especially striking.

On how public opinion is less tolerant than the law.

A very smart observation and truer now than it ever has been:

A Houyhnhnm, we are told, is never compelled to do anything, he is merely ‘exhorted’ or ‘advised’ … This illustrates very well the totalitarian tendency which is implicit in the anarchist or pacifist vision of society. In a society in which there is no law, and in theory no compulsion, the only arbiter of behaviour is public opinion. But public opinion, because of the tremendous urge to conformity in gregarious animals, is less tolerant than any system of law.

When human beings are governed by ‘thou shalt not’, the individual can practise a certain amount of eccentricity: when they are supposedly governed by ‘love’ or ‘reason’, he is under continuous pressure to make him behave and think in exactly the same way as everyone else.

On the politicisation of literature.

I think this comes and goes in waves but it’s interesting to know how far back the tendency can be traced. Most people seem to believe the obsession with political correctness goes back to the 1960s. But this essay (‘The Prevention of Literature’) was written in 1946:

Of course, the invasion of literature by politics was bound to happen. It must have happened, even if the special problem of totalitarianism had never arisen, because we have developed a sort of compunction which our grandfathers did not have, an awareness of the enormous injustice and misery of the world, and a guilt-stricken feeling that one ought to be doing something about it, which makes a purely aesthetic attitude towards life impossible.

No one, now, could devote himself to literature as single-mindedly as Joyce or Henry James. But unfortunately, to accept political responsibility now means yielding oneself over to orthodoxies and ‘party lines’, with all the timidity and dishonesty that that implies. As against the Victorian writers, we have the disadvantage of living among clear-cut political ideologies and of usually knowing at a glance what thoughts are heretical. A modern literary intellectual lives and writes in constant dread – not, indeed, of public opinion in the wider sense, but of public opinion within his own group.

As a rule, luckily, there is more than one group, but also at any given moment there is a dominant orthodoxy, to offend against which needs a thick skin and sometimes means cutting one’s income in half for years on end. Obviously, for about fifteen years past, the dominant orthodoxy, especially among the young, has been ‘left’. The key words are ‘progressive’, ‘democratic’ and ‘revolutionary’, while the labels which you must at all costs avoid having gummed upon you are ‘bourgeois’ [and] ‘reactionary’

On “good bad literature” and how being clever doesn’t make you a good novelist.

I think this is completely correct:

The existence of good bad literature – the fact that one can be amused or excited or even moved by a book that one’s intellect simply refuses to take seriously – is a reminder that art is not the same thing as cerebration. I imagine that by any test that could be devised, Carlyle would be found to be a more intelligent man than Trollope. Yet Trollope has remained readable and Carlyle has not: with all his cleverness he had not even the wit to write in plain straightforward English.

In novelists, almost as much as in poets, the connection between intelligence and creative power is hard to establish. A good novelist may be a prodigy of self-discipline like Flaubert, or he may be an intellectual sprawl like Dickens. Enough talent to set up dozens of ordinary writers has been poured into Wyndham Lewis’s so-called novels, such as Tarr or Snooty Baronet. Yet it would be a very heavy labour to read one of these books right through. Some indefinable quality, a sort of literary vitamin, which exists even in a book like If Winter Comes, is absent from them.

On the unknowability of children.

I have no idea whether or not it’s true that children don’t like adults — perhaps it’s just true of the young Orwell. But it’s an original and interestingly unsentimental idea:

And here one is up against the very great difficulty of knowing what a child really feels and thinks. A child which appears reasonably happy may actually be suffering horrors which it cannot or will not reveal. It lives in a sort of alien under-water world which we can only penetrate by memory or divination. Our chief clue is the fact that we were once children ourselves, and many people appear to forget the atmosphere of their own childhood almost entirely. Think for instance of the unnecessary torments that people will inflict by sending a child back to school with clothes of the wrong pattern, and refusing to see that this matters! Over things of this kind a child will sometimes utter a protest, but a great deal of the time its attitude is one of simple concealment.

Not to expose your true feelings to an adult seems to be instinctive from the age of seven or eight onwards. Even the affection that one feels for a child, the desire to protect and cherish it, is a cause of misunderstanding. One can love a child, perhaps, more deeply than one can love another adult, but it is rash to assume that the child feels any love in return.

Looking back on my own childhood, after the infant years were over, I do not believe that I ever felt love for any mature person, except my mother, and even her I did not trust, in the sense that shyness made me conceal most of my real feelings from her. Love, the spontaneous, unqualified emotion of love, was something I could only feel for people who were young. Towards people who were old – and remember that ‘old’ to a child means over thirty, or even over twenty-five – I could feel reverence, respect, admiration or compunction, but I seemed cut off from them by a veil of fear and shyness mixed up with physical distaste.

Oddly I have shaken the hand of this baby - Orwell’s son Richard Blair - who I was briefly introduced to at a party at the Senate House library in London.

Thanks for reading Cultural Capital! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

From Cultural Capital via this RSS feed