Small Durand Gardens by Howard Hodgkin

Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital! In The Times this week I wrote about the under-discussed problem of boomer phone addiction. Everyone panics — rightly — about kids and phones. But there is evidence that total screentime among over 65s (including TV and iPads) may be even higher than it is for users in their twenties.

Thanks for reading Cultural Capital! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

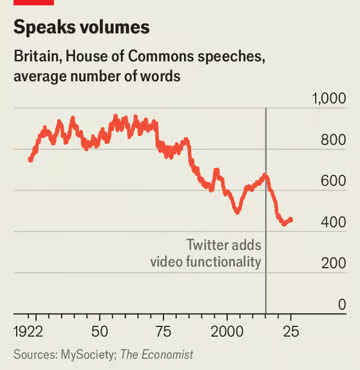

Post-literate parliamentI missed this piece in The Economist from last year. In the UK parliament speeches are getting shorter and less complex.

The standard has declined especially sharply recently and the cause seems to be our old friend short form video:

In 1938 the average speech was almost 1,000 words long. In 1965 James Callaghan delivered a budget speech that was almost 19,000 words: less a speech than a novella. Until 1970 the average was still almost 900. Then they start to shrink—dramatically so after 2015, when video functionality appears on Twitter (now X). Last year the average was 460: less a novella than a few Tweets.

Interestingly, a recent computational analysis of congressional speeches in the journal Nature Human Behaviour found a similar trend in American politics. Analysis of speakers from both parties found “a decline in the prevalence of evidence-based language” and towards “intuition-based language” since the 1970s. One factor in the decline, the authors suggest is “the impact of media”, especially the introduction of television cameras which turn “congressional speeches into orchestrated performances aimed at capturing media attention” resulting in a “reduced focus on meaningful intellectual discourse and nuanced policy discussions within the legislative body”.

Beware declining super powersRegular readers know how much I revere the FT’s Janan Ganesh. This is a really good column on why Trump’s America is lashing out so eratically. It seems absurd to say America is declining. But in relative terms it is thanks to the challenge to its hegemonic power from China. It may usefully explain the events of the last few weeks:

Because the performance of the US this century has been so awesome in absolute terms — economically, technologically — the nation’s relative decline can be hard to visualise. But it is there, in the limited effectiveness of US sanctions over recent years, in the struggle to stay ahead on artificial intelligence, and in the strategic assets that China dares to own in the western hemisphere. The military gap over China is not what it was at the turn of the millennium…

Always beware the downwardly mobile. Those of us who live a better life than we were born into cannot begin to understand the trauma of going in the opposite direction. A small drop in status can unhinge people, even if their absolute position remains good. It was the Weimar middle class, inflated out of their savings during the slump, who turned to the National Socialists in elections, not necessarily the worst-off. In geopolitics, the same process plays out on the largest scale. What is Russia’s war in Ukraine if not a protest at its reduced status since the Soviet collapse?

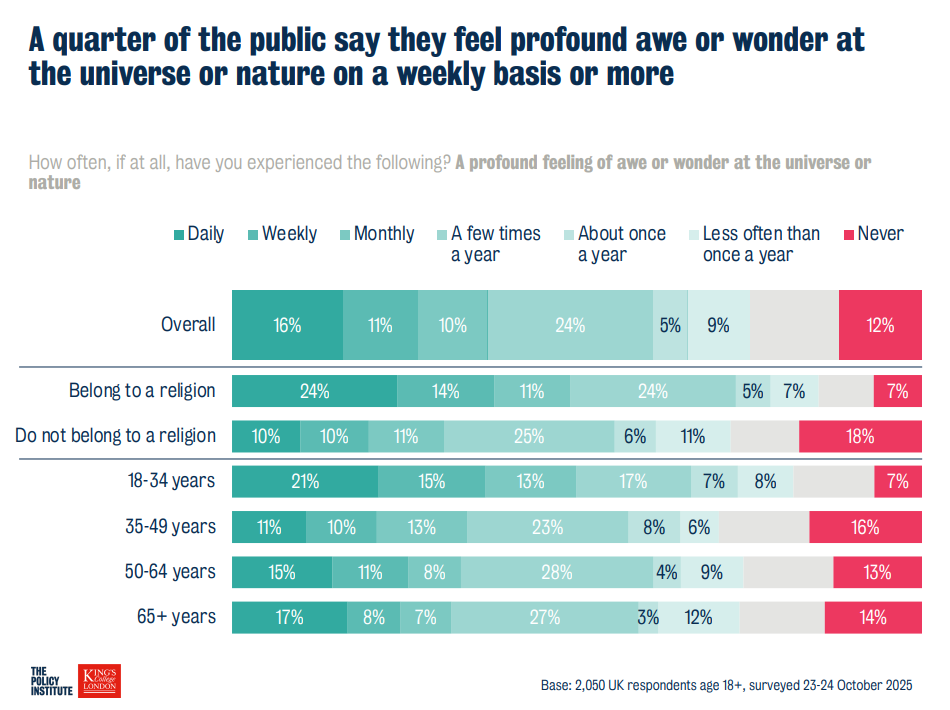

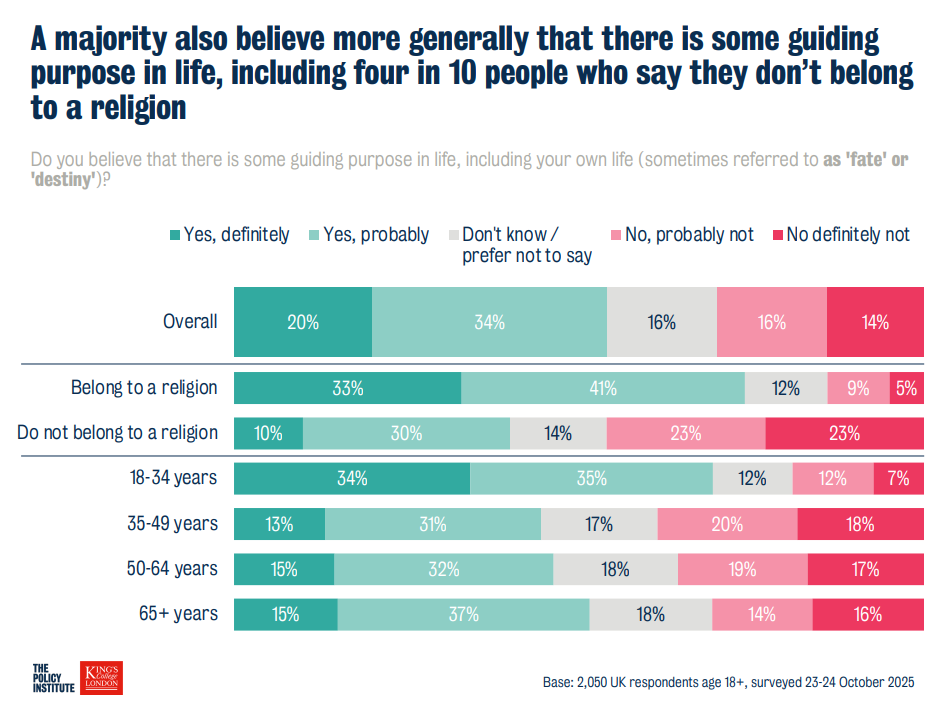

Thankfulness, awe and wonderThis is a great study from King’s College London investigating the vaguer non-religious more “woo-woo” public attitudes to spirituality. It examines the prevalence of feelings of “thankfulness, awe and wonder”.

Apparently “a quarter of the public say they feel profound awe or wonder at the universe or nature on a weekly basis or more”. Weekly OR MORE! My feeling is that anyone who feels profound awe at the universe on a daily basis must be insufferable to be around.

I also found this interesting: “a majority also believe more generally that there is some guiding purpose in life”. It’s curious that “younger people aged 18 to 34 stand out as hugely more likely to believe there is a guiding purpose in life, with seven in 10 (69%) holding this view, including more than three in 10 (34%) who say they definitely believe there is such a purpose.”

I have a friend who sometimes remarks that “everything happens for a reason” might be the most widely held spiritual belief in the secular West. When you listen out you hear versions of it everywhere — “it was meant to happen”, “it wasn’t meant to be”, “things always work out”. You get this even among people who would otherwise insist that they are entirely rational. The KCL study is a useful reminder of the ways human beings seem to default to vaguely spiritual ways of thinking about life without really meaning to.

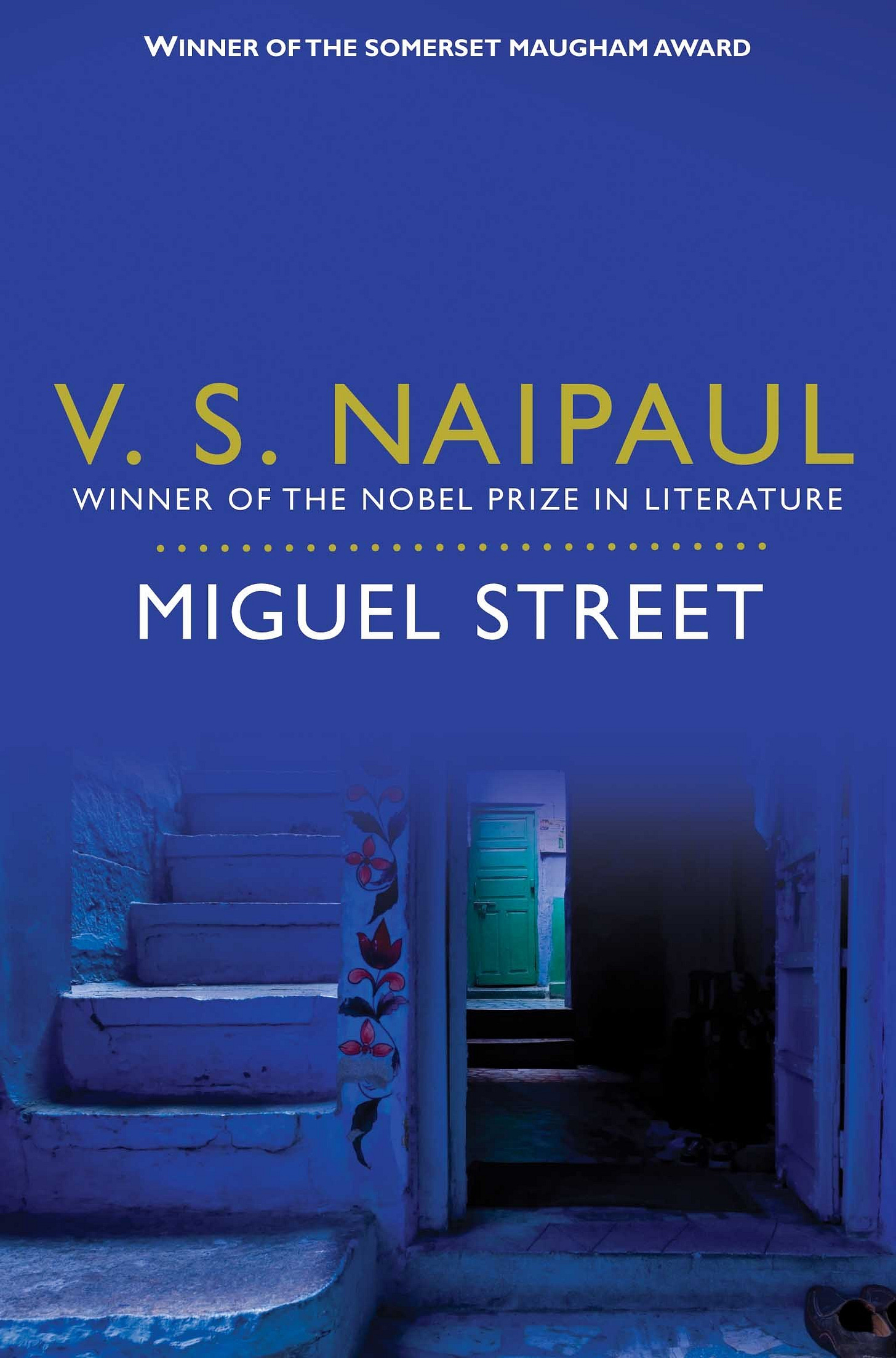

Book recommendation: Miguel Street by VS NaipaulI increasingly realise if there’s one quality that unites everyone whose literary taste I rate it’s a love of (or at least respect for) the novelist VS Naipaul. I think there’s a case he was the greatest English postwar writer. There are so many sides to him. You have the baggy Dickensian sprawl of A House for Mr Biswas, the austere unflinching portraits of dysfunctional colonial societies such as A Bend in the River, the er … highly problematic opinionated travel writing.

Last week I read Naipaul’s short story collection Miguel Street, the first book he ever wrote (though the third that was published). I have to say it just blew me away. Miguel Street is a beautiful book: a series of tragi-comic vignettes of life in Port of Spain where Naipaul grew up in poverty before leaving Trinidad for England in 1950 on one of a handful of British government scholarships to Oxford.

Miguel Street was a new side (to me) of Naipaul. It’s a much lighter and more humane book than his sometimes austere later writing. I thought it was so funny and charming and tender and sad (to use all the blurb clichés). I don’t think a work of fiction has struck me this way since I read The Corner That Held Them by Sylvia Townsend Warner about this time last year.

The story that I most loved was ‘B. Wordsworth’. The narrator (a small boy) encounters an oddball wandering tramp figure who claims to be a poet, calling himself “B Wordsworth” (for “Black Wordsworth”, as opposed to “White Wordsworth”). It’s only 2,500-ish words and you can read it online — scroll down to page 38. Here is a flavour:

B. Wordsworth said, ‘Now, let us lie on the grass and look up at the sky, and I want you to think how far those stars are from us.’

I did as he told me, and I saw what he meant. I felt like nothing, and at the same time I had never felt so big and great in all my life. I forgot all my anger and all my tears and all the blows.

When I said I was better, he began telling me the names of the stars, and I particularly remembered the constellation of Orion the Hunter, though I don’t really know why. I can spot Orion even today, but I have forgotten the rest.

Then a light was flashed into our faces, and we saw a policeman. We got up from the grass. The policeman said, ‘What you doing here?’

B. Wordsworth said, ‘I have been asking myself the same question for forty years.’

How AI destroys institutionsHere is an interesting new paper by two Boston law professors laying out the ways AI poses an existential threat to human institutions. Institutions, the paper argues, are our “super power”, enabling complex and rational human behaviours at large scale.

Unfortunately, they suggest “If you wanted to create a tool that would enable the destruction of institutions that prop up democratic life, you could not do better than artificial intelligence.”

AI poses a number of problems for institutions, the paper argues. It is incapable of taking intellectual risks — something that human employees do all the time which keeps institutions flexible and innovative.

And, importantly, an institution filled with human employees is full of nodes of resistance. An institution made up of humans is just full of potential opportunities for them to push back at questionable decisions, call out abuses, argue with their bosses and generally question things. To strip out humans from an institution is to remove all potential challenges to its hierarchy and make everything eerily (dangerously) smooth:

An AI system also cannot challenge the status quo, because its voice has no weight. This is part of what we mean when we say AI systems flatten the institutional hierarchies. Even assuming a lack of sycophancy, when AI systems replace human decisionmakers, institutions are deprived of a source of moral courage and insight, which is necessary for institutions to adapt and thrive. Stanislav Petrov famously saved the world from nuclear warfare when he disobeyed orders and refused to alert his superiors that the nuclear early-warning system reported that missiles had been launched from the United States, which turned out to be a system error. Whistleblowers within institutions put their livelihood and personal wellbeing on the line, to say nothing of the countless humans who speak up and challenge their superiors’ decisions, even though it could cost them their jobs. AI systems have no skin in the game and no impetus to challenge decisions within the hierarchy.

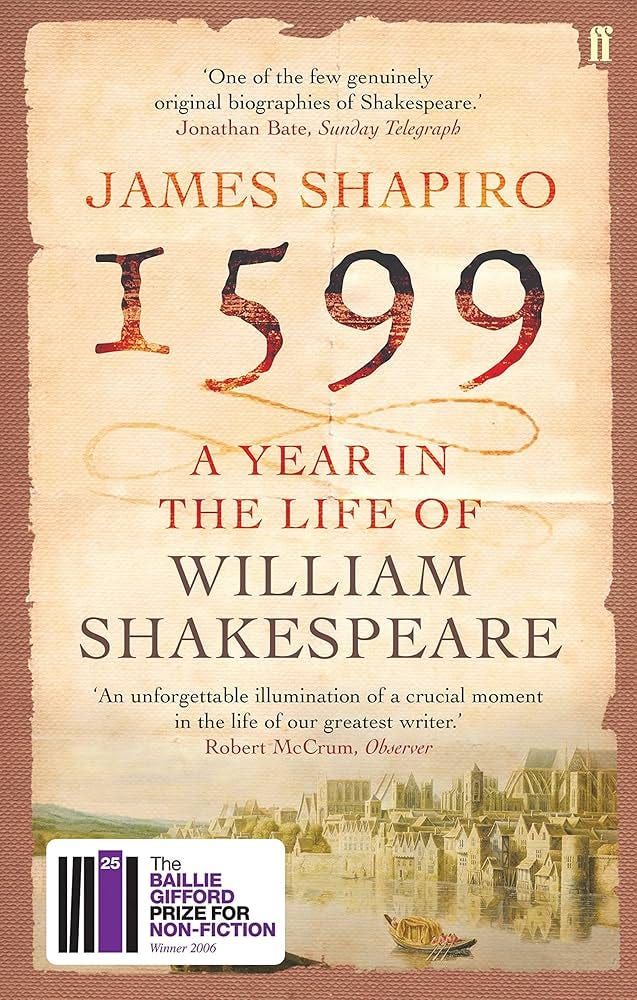

A year in the life of ShakespeareAnother book recommendation. I’ve also just finished James Shapiro’s book 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare. I loved this book too and highly recommended to anyone looking for an engrossing and well-constructed non-fiction book. You’ll fly through it. You don’t have to care about Shakespeare (or entirely buy Shapiro’s highly historical readings of the plays) to enjoy it. It’s a vivid and convincing portrait of a year in Elizabethan England: the Earl of Essex’s disastrous campaign in Ireland, life in the streets of London, intrigues at court, competition between theatre companies.

I think it’s because we don’t know much about Shakespeare’s life that there’s something so compelling about catching glimpses of the greatest genius of all time in little anecdotes. For instance this is pretty much all we know directly about Shakespeare’s character:

When the seventeenth-century biographer John Aubrey asked those who were acquainted with Shakespeare what they remembered about him, he was told that Shakespeare ‘was not a company keeper’, and that he ‘wouldn’t be debauched, and, if invited’, excused himself, saying ‘he was in pain’. The image of Shakespeare turning down invitations to carouse with such a lame excuse has a strong ring of truth…

I also love the little glimpses we have of Shakespeare’s fans. People knew he was special:

Spenser had rewritten the course of English epic and pastoral. Shakespeare would soon enough take a turn at rewriting each in Henry the Fifth and As You Like It – and would have appreciated the vote of confidence expressed in an anonymous university play staged later this year in which a character announces: ‘Let this duncified world esteem of Spenser and Chaucer, I’ll worship sweet Mr Shakespeare.’

Thanks for reading Cultural Capital! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

From Cultural Capital via this RSS feed